eBay

Audio By Carbonatix

This past year, I made a five-hour pilgrimage to West Colfax Avenue. Among the nearly 100 different Denver neighborhoods, this is the one I grew up in. Though I have visited many times since moving away, I had not seen my old neighborhood in its entirety and walked through it methodically in over half a century. So when I came to town on business from the East Coast, where I now live, nostalgia seized me. I wanted to know how the neighborhood had changed, and I wanted to remember how it once had been.

Starting out from my hotel downtown while trying to orient myself, I was reassured by the gold-domed Colorado Capitol on the skyline, where it has stood for well over a century. I passed the Paramount Theatre, built in 1930 and the last movie palace still standing downtown, where we saw movies as kids. Suddenly I was ten again, walking with my mom to a dentist appointment in the Republic Building nearby. That building was demolished in the early 1980s to make way for Republic Plaza, now the tallest building in Colorado. The Rocky Mountain views from a high floor inside Republic Plaza seemed so much better than the views from smaller buildings decades ago.

I passed the site of the old Municipal Auditorium and Municipal Arena, where we swayed and stomped as teenagers at a Rolling Stones concert more than fifty years ago. Those buildings, now transformed into magnificent theaters, were the site of the 1908 Democratic National Convention shortly after the Auditorium (now the Ellie Caulkins Opera House) was built. The Arena (today the Buell Theatre) briefly became America’s second-largest indoor arena after Madison Square Garden. But as much as Denverites exulted over the Nuggets’ first-ever NBA championship last year, they barely remembered the forerunner Denver Rockets who played here until the mid-1970s.

When I reached West Colfax, I stopped at the ornate Italian Renaissance building that houses the U.S. Mint. On a grade-school trip long ago, I was impressed by huge buckets of glistening copper pennies. Our teacher stressed Denver’s importance – not only as Queen City of the Plains, but also home to one of very few Mint branches nationwide.

The State Capitol in the ’50s.

Keystone/Getty Images

At nearby Speer Boulevard, along the path of Cherry Creek where the first mid-nineteenth-century gold prospectors had erected their cabins, I hopped on a Number 16 bus that was once a Number 64 bus. The bus went over what used to be a ramshackle viaduct above the South Platte River when the speed limit on Colfax was 40 miles per hour, not 30. It was at the confluence of that river and the creek that Denver was founded in 1858, a fact as central to the city’s history as mining and railroads.

The bus traveled over a sleek roadway that continues as the western wing of Colfax Avenue. Running 26 miles from east to west, Colfax is purportedly the longest surface-level commercial street in the United States. But I had forgotten that the Westside refers to that side of the South Platte. I had also forgotten the long-ago, manure-laden smell of the stockyards beneath the old viaduct. Ranchers sent their cattle there to be fattened before being dispatched to the nearby slaughterhouses, where my brother and I worked occasionally during college. This once made Denver more of a cowtown than it is today.

In the 1950s, the Westside contained a mix of Mexican Americans, some of whom had originally come to Colorado as migrant workers to help farm sugar beets, and a significant number of recently arrived Holocaust survivors. These traumatized Jewish immigrants settled in a supportive, pre-existing community that had expanded early in the twentieth century, in part for reasons of health. The semi-arid Colorado climate was seen as conducive to better treatment of poverty-influenced, urban respiratory ailments, especially tuberculosis.

The original National Jewish Hospital, today touted as the nation’s leading respiratory hospital, was established in Denver in 1899 on a non-sectarian, no-charge basis. The Jewish Consumptive Relief Society, or JCRS, began five years later farther west on Colfax. Some JCRS patients who coughed up blood until their lungs gave out, including those who came with little money and without family, were buried at a cemetery on Colfax not far from the foothills of the Rockies. It is aptly named Golden Hill for the seeming eternity of spectacular snowcapped mountain vistas it affords. After the sanitorium finally closed, part of the grounds became the JCRS Shopping Center, now home to Casa Bonita, the state’s most famous Mexican restaurant.

I had gradually learned the history of my own Denver Ashkenazic Jewish community, but that history, I now realize, is inevitably partial. Hispanics made up about 10 percent of the city’s population during the mid-twentieth century, while today it has climbed to over 30 percent. Yet I knew much less about those communities. And barely a century before I was born, the northwest Denver frontier was a very different place — inhabited by the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes from the midwestern plains who had migrated there. There were also Utes in Denver from the western and southern parts of the state among a European-American population totaling fewer than 5,000 in 1860. Denver then had one bank, two hotels and about four dozen gambling establishments. Many fortune seekers abandoned their Cherry Creek cabins and left town after a hoped-for gold rush fizzled. But Denver endured as a city. One travels to a place to know it better. Here, what I did not know until I did some reading later became a revelation, too.

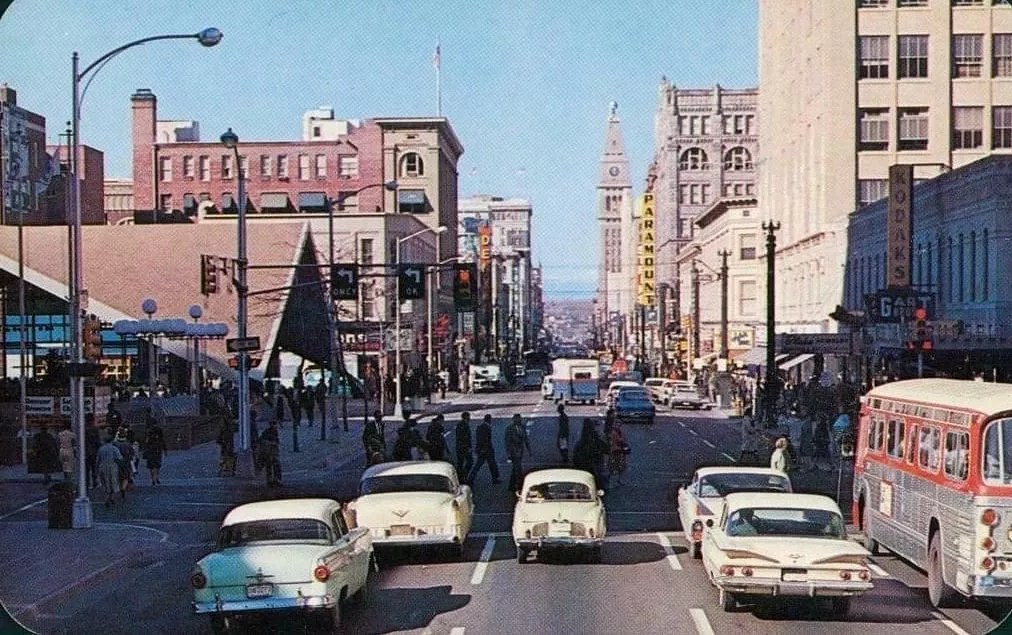

16th Street in the 1960s.

Historic Denver

Denver’s Jewish community is almost as old as the organized city itself, but the less traditional German Jews who arrived first lived mostly on the fancier east side of the South Platte. The Westside Colfax neighborhood catered to a population that was generally more traditional and less affluent in an area that was about twenty blocks long and five blocks wide.

To the east, our neighborhood was bounded by Federal Boulevard, near the previous Mile High Stadium, where the Denver Broncos used to play and where, at a much smaller stadium, we attended Triple A minor league Denver Bears games before Denver finally secured a Major League Baseball franchise in the 1990s.

To the west was Sheridan Boulevard, at the boundary of a more economically disadvantaged city, Lakewood in Jefferson County, slightly closer to the Rockies and the 300 days of sunshine that inspired us every day. I remembered my mother hanging the wash on a clothesline in that breezy Colorado sunshine because we had no electric dryer.

To the south loomed a natural barrier now called the Lakewood Gulch (we called it the Gully), formerly a no-person’s-land full of weeds, cigarette butts and broken bottles where we horsed around. But that wilderness is now cleared out. Since 1994 it has been part of an elegant light-rail system.

Two blocks to the north of Colfax, parallel to at least two-thirds of the area streets, is Sloan’s Lake and its park, scene of our softball and touch football games, to say nothing of a skeet-shooting range, tennis courts and some fishing and boating. According to Denver historians Stephen J. Leonard and Thomas J. Noel, in 1876 Sloan’s Lake was the scene of a large gathering that had come to watch Ute ritual dancing. In the early 1890s it hosted an amusement park that quickly went out of business.

Running alongside the west end of the lake, just barely inside Lakewood, was the A&W Root Beer outlet to which we often rode our bikes. There was also the Lakeshore Drive-In that specialized in low-budget horror movies. Both are also now gone, disproving H.L. Mencken’s observation that a home’s “essence lies in its permanence.” Home is as changeable as most everything else.

Above the lake there is a new, wealthier area, still called Highland, which had once been a separate city before it merged into Denver. To me, it was associated with the earlier location of another amusement park, Elitch Gardens, and its rides and games and summer picnics. But I was surprised to learn that one can now access Highland through the eye-catching Millennium Bridge downtown, which, though erected in 2002, I had never seen.

Heading west on Colfax Avenue,

Denver Public Library

I started my walk at 14th Avenue and Federal Boulevard after getting off the bus, zigzagging between Colfax and the Gulch, ultimately covering the alphabetically ordered streets from Grove through Zenobia.

I stopped to use the bathroom at a Latino Pentecostal church a few blocks away after a caretaker let me in. Those streets, such as Hooker, Julian, Irving and King, were once at the heart of the Jewish community. Today that community has all but vanished from those streets, parts of it having relocated long ago farther west and become more devout and self-contained, as few communities remain static. A yeshiva or Jewish parochial high school formed in the late 1960s, formerly at 14th and Quitman, is now Confluence Ministries, an evangelical Protestant outpost. The high school’s dormitory on Perry Street has been replaced by a large medical office building. There was once what we called an old folks’ home on Meade Street, where my parents were volunteer visitors. Sometimes my brother and I tagged along to see how the old folks were doing. Now, suddenly, I will soon be one of them.

A largely Chicano Catholic community gradually replaced the older Jewish community. While the two groups did not mingle much in those days, owing to linguistic, religious and cultural differences, they got along fairly well. There was also some neighborhood diversity even then. Our kind next-door neighbors for over 25 years consisted of the larger Martinez family. One thing the two communities had in common is that both slowly overcame opposition from a so-called Anglo-Protestant majority that sometimes sought to exclude them both from jobs and clubs and other neighborhoods. On the other hand, African and Asian-Americans were almost completely absent from our neighborhood. They would come later.

As I continued my walk, I saw that the circa 1892 St. Anthony’s Hospital complex, where I was born, had been completely torn down except for a small Catholic chapel left standing amid the new apartment blocks. These are topped off by a burger and booze joint on Raleigh and Conejos, brightly lit, glass-enclosed, and teeming with young professionals who have moved in. It seemed way too cool for our formerly staid neighborhood.

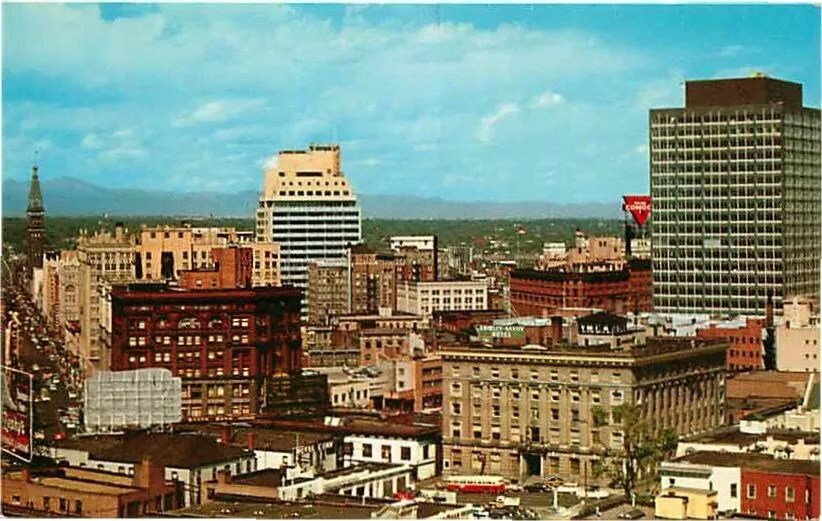

Downtown Denver in 1964.

Robert J. Boser, EditorASC, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Exiting on Stuart Street, I came upon the massive Hebrew Educational Alliance, built in a flush of post WWII optimism that underlay extensive church and synagogue building all over America. (There were no Westside mosques or Hindu temples then.) The Alliance was our family synagogue in my pre-bar-mitzvah years. Perhaps my proudest moment as a preteen was winning a substantial silver trophy for some lucky series of games in their youth bowling league. I held on to the trophy, but I have barely gone bowling since then. As for skiing in the 1960s, it was not yet as widely popular. Vail had opened only in 1962, and our family, at least, still saw skiing as a sport for rich people.

The Alliance was so big it occupied the entire east-west block to Tennyson, with Colfax Elementary School across the street. As a four- or five-year-old, I remembered holding my mom’s hand as she first took me there for arts-and-crafts activities. Heading down Tennyson to the lake, everything was quiet as I passed the homes of friends’ parents we once knew, wondering if at least one of them is still living there, albeit by now in her late nineties. In the large park that surrounds the lake, I quickly found the asphalt running path. It was filled with many more leisurely walkers in a more relaxed, pre-social-media era.

Vrain to Winona, from Sloan’s Lake to Colfax, contained the four-square-block area where my family lived at three different addresses over the course of nearly four decades, until the late 1980s. It was then that my parents moved into an apartment on the Eastside, where my brother and part of his family still live.

My nephew mentioned that a lakefront house on 17th and Vrain (nice but hardly lavish) had just sold for well over one million dollars. That meant our old neighborhood had grown more desirable since the mid-1960s, when my parents purchased our 2,100-square-foot home with a basement, on Winona Court near Colfax, for $17,500 – including furniture. It had a small front lawn and a backyard, too.

Walking up from the lake brought me to 1655 Vrain, where I lived from ages one to ten. The Vrain address was not a house. It was more of a rambling estate, a large 1920s structure split up into smaller apartments like ours that were somewhat decrepit even then. The property was framed by weathered stone gates and a large open area where we played cops and robbers. It is very different from the much more confined Manhattan apartment building in which my own children grew up. And they never had a proper back porch with huge pine trees in the background through which the winter wind howled and rattled outside our bedroom windows. That was our world.

Eddie Bohn’s Pig ‘n’ Whistle was a landmark on West Colfax Avenue.

colfaxave.org

West Colfax had always been a bit seedy and remains so, with a series of down-market motels bearing upscale names like the Aristocrat, as well as rows of used cars and trailers for sale. As a youngster, an errant ball I had thrown broke the window of an empty trailer. I still wince when I recall over sixty years later that I told nobody and never made amends.

Eddie Bohn’s Pig ‘n’ Whistle was the most distinctive motel in the neighborhood, the one with the best pool. A few relatives stayed there when visiting from out of state. It is now defunct, and the bright blue and pink pool area has been filled in, but the name and original sign remain to mark off a busy and jarring pot dispensary. Recreational marijuana has now been sold legally in Colorado since 2014, a development that would have astonished everyone during my childhood years.

Walking west on Colfax, with its stunning panorama on most days, brought me to Denver’s western border with Lakewood, which contained our barber, our piano teacher, an old-fashioned pool hall and a small bicycle repair nook that was always dark, dusty and dank. West Colfax was once lined with quaint shops like those, including mom-and-pop groceries, bakeries and drugstores. But no more. My oldest friend Mark’s Eastern European parents ran a small poultry store there. He wanted to do better, and so he became a doctor and, like me, left for a bigger city. Another friend’s immigrant father ran his own home-delivery fresh fruits and vegetables truck. That kid, like my brother Phil, also became a doctor, but both remained in Denver.

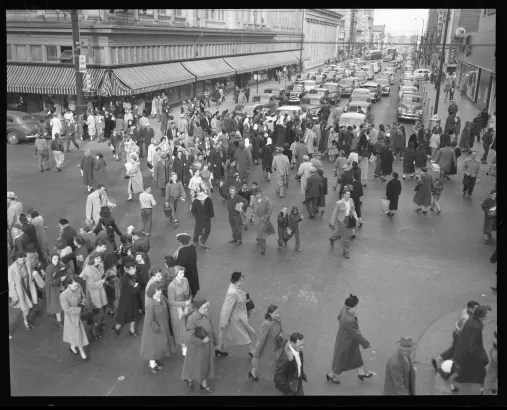

Intersection of 16th and Champa streets in the ’50s.

Denver Public Library

Meanwhile, at the end of my walk, just beyond Zenobia on Sheridan Boulevard, the down-and-out were congregated at a gas station. On the corner of Colfax and Sheridan is Walgreens, which was a Miller’s supermarket in the 1960s. Seeing it conjured one final, almost-forgotten memory of my parents’ first months together in the West Colfax area of Denver.

My dad initially visited Denver in 1948, after parts of three years as a soldier during WWII, including service in an artillery battalion in Europe. He was seeking a fresh start, like many American veterans, in a place that would remind him less often of the war and the economic difficulties his family endured in New York City during the Great Depression. He was also ambitious — the only one of six siblings to go to college. My mom was Canadian. She had worked as a bookkeeper after graduating from high school. Her father was a milkman who, in the 1920s, still delivered his wares by horse and wagon.

Dad arrived at the now beautifully refurbished Union Station on a cross-country train trip. He was so captivated by Denver, then still a calm, mid-sized city, that he returned permanently with his bride in 1953. Mom was then first exposed to, and ultimately became a fan of, country music on AM radio. Although my dad was a lawyer by then, and later a law professor at the University of Denver, he told my mom that when he could not find a job right away, he became so despondent that he walked into Miller’s supermarket and asked if he could bag groceries. They turned him down, and the rest is history.

Gordon Mehler is a lawyer and proud Denver native whose writings have appeared in the Denver Post, as well as the Atlantic and Newsweek, the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal.

Westword publishes commentaries about Denver issues on the weekends. Have one you’d like to share? Email editorial@westword.com, where you can also respond to this essay.