Danielle Lirette

Audio By Carbonatix

To do justice to Atelier by Radex, which just celebrated its one-year anniversary, I should write a biography, not a review. What started as a straightforward critique of a classic French restaurant has turned into anything but, and I’ve been wondering how to put it all into words without resorting to the frustrating Dickensian technique of serializing and stopping at a cliffhanger. Yes, there’s that much going on at this quaint spot, which occupies the former home of Il Posto on a tree-lined street in Uptown and transports you either to the 1980s or to some spot in Paris that lives on in your rose-colored memories. Given the influx of recent Mile High residents, it’s a safe bet that most guests don’t recognize the name behind the operation: Radek Cerny. But the man who presents the chalkboard of specials with a heavy French accent and displays a strong disdain for New World wines isn’t Cerny. The chef/owner is the one behind the stove wearing a golf shirt and the signature hat that inspired the menu’s logo. As the story goes, the hat was a gift from JoÁ«l Robuchon in Vegas, but the combo makes Cerny look like a Florida retiree ready to head out for a good walk spoiled. When you’ve been at the stove for forty-plus years, you earn the right to wear whatever you want.

Radek Cerny in the kitchen of Atelier by Radex.

Danielle Lirette

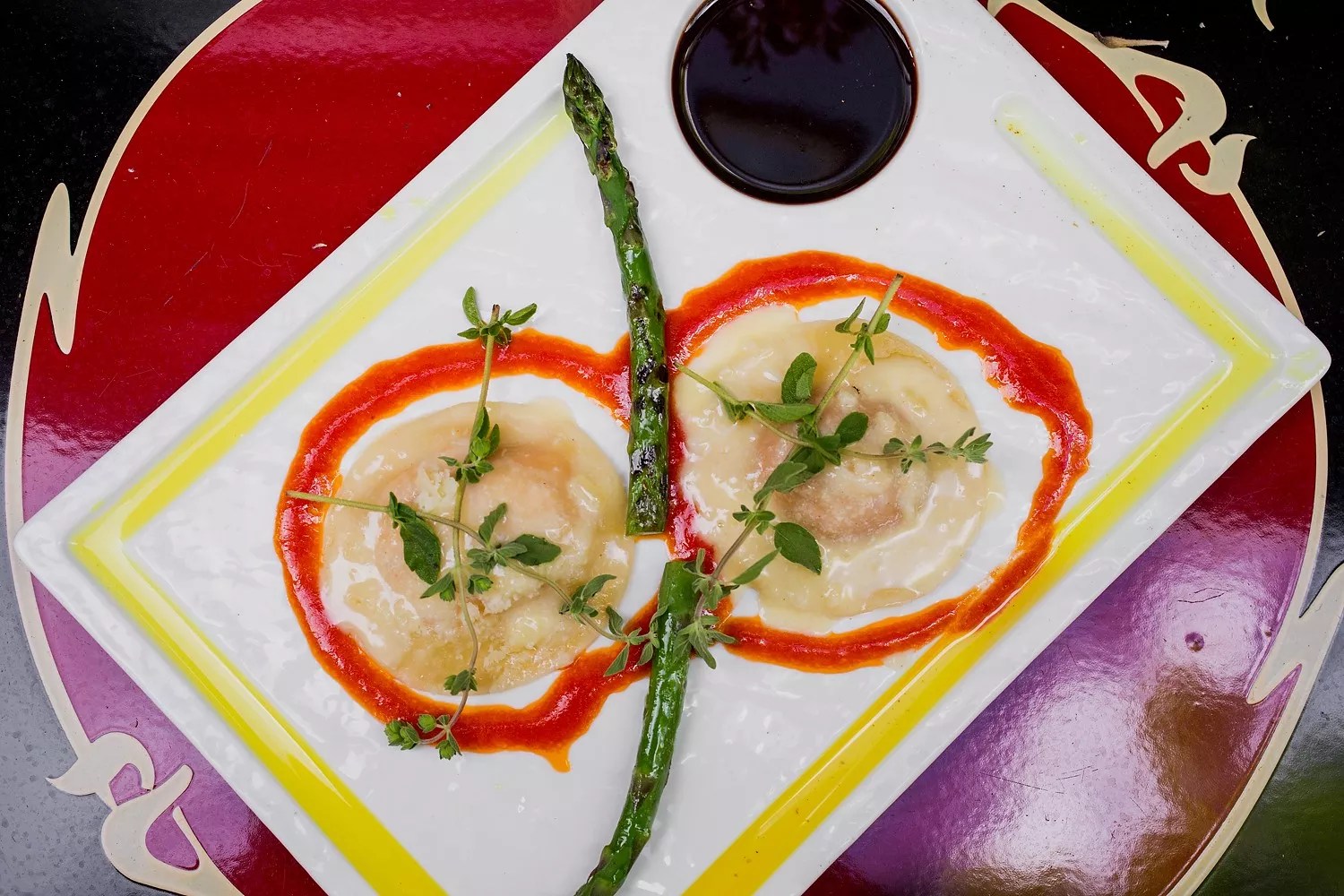

In Cerny’s heyday in the ’90s, he was a powerhouse, at the helm of a local restaurant empire that included a long line of mostly French and Italian restaurants. Still hyped from close encounters with such titans as Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Paul Bocuse and Roger Verge, for whom he either worked or staged in the ’80s, the Czech native once commanded as big a reputation in Denver as our top chefs – Jasinski, Rodriguez, Seidel, MacKissock, Guard, Bonanno – do now. But rather than cooking the food of his homeland, as #authentic and #betrue chefs might feel emboldened to do now, Cerny did what was expected of him: He put out high-brow continental as he opened twenty-some restaurants, including Cherry Creek’s Papillon, living through the pain of over-extension and burnout that some of our current chefs might read as a cautionary tale. All the while, he’s cooked lobster ravioli so transcendent, you want to weep from gratitude, drying tears only to ask for more bread to sop up the champagne beurre blanc. If you missed the dish back then, either because you weren’t born or because you were paying taxes elsewhere, it’s not too late. Lobster ravioli is still on the menu, and it’s as conversation-stopping as ever, with expansive, paper-thin wrappers and luxurious centers full of lobster.

By the time I moved to Denver, nearly fifteen years ago, Cerny’s star had fallen and was again on the rise. In 2004, Westword‘s Best of Denver acknowledged the end of Cerny’s sold-off empire and honored his then-new Boulder restaurant (still open and now run by his daughter), presumptuously called L’Atelier – The Artistry of Radek Cerny. The award, for Best Rebirth of a Chef, praised “Radek re-energized. Radek times ten. Like an aging prizefighter getting his second wind.” If we were celebrating his rebirth back then, is there even a name for Cerny’s third wind at his current endeavor? Or is he the Helen Mirren of restaurateurs, reinventing himself for every generation?

The thing is, Cerny doesn’t reinvent himself so much as do the same thing. (Or someone else’s thing: L’Atelier is the name of Robuchon’s restaurants, too.) And when enough time has gone by, the same thing feels, well, new. Those gleaming copper pots on the walls look novel when you’re used to today’s industrial-Scandinavian aesthetic, but they also bring to mind the copper pots in the kitchen at Restaurant Lafayette, the famed New York hotel restaurant where Cerny worked under Jean-Georges in the ’80s. The menu itself reads like a greatest-hits collection of Cerny’s career. That lobster ravioli, the one your server talks up as Atelier’s signature dish, has been stuffed and served thousands of times; Cerny learned to make it in southern France more than thirty years ago. Red curry seems edgy on a French menu, until you see it not once (in a special of drunken mushrooms), not twice (lending a rosy glow to coconut-milk-splashed mussels), but three times (in the brick-red sauce for panier de diables, with shrimp, dried chiles and wild mushrooms). Does it matter that Cerny picked up the idea for red curry from Jean-Georges, who made his name by daring to blend Asian ingredients with French technique? Or that the clever DIY preparation – when you do as your server suggests and dump the hot shrimp and saucy mushrooms over greens from Cerny’s garden – also came from someone else, a chef in Chicago? Not in the slightest. The mussels, in broth that warrants a request for more bread to sop it all up, are spectacular; the drunken mushrooms with a splash of brandy and dollops of goat cheese are bold; and the shrimp over salad is mesmerizing, the greens wilting slightly, bringing welcome freshness to that spice-drenched sauce.

Atelier’s time-honored appetizer-entree format also manages to appear fresh, given how thoroughly small plates have upended menu design. There are no small plates here; really, the plates are huge. Mussels arrive in a porcelain claw-foot bathtub that towers over the table. (Too bad Atelier hasn’t adopted the coastal trend of restaurants selling linens and dishware along with food; I would’ve ordered one of those fabulous tubs on the spot.) Entrees make a statement on white platters that look like Mick Jagger’s lips – gargantuan, foot-plus-long affairs with curved sections, one filled with swirls of balsamic or demi-glace and the others with the protein you ordered, plus whatever starches and vegetables Cerny sees fit. Standouts include lamb chops, seared and pink within; saltimbocca ibérico, aka pork cutlet topped with high-end ham, melted Gruyère and marsala; and the “best beef on the block,” in my case filet with green peppercorns. The cassoulet underneath the lamb had been rushed, however, as has every cassoulet I’ve had in recent memory. Rather than a multi-layered explosion of meaty extravagance patiently cooked for days, this one had a medley of white beans with all the nuance of tomato sauce.

Radek Cerny’s signature lobster ravioli.

Danielle Lirette

One entree, “Le homard TV dinner,” was actually conceived to fill a behemoth white plate that Cerny saw and couldn’t live without. The result is like a bento box, with appetizer, entree and dessert rolled into one. There’s creamy risotto with a hint of citrus to clamor against richness. Gratin dauphinois alternately dried out and divine, depending on the night and how late I ordered it. (It’s ready at start of service.) Lobster tail and shrimp scampi bobbing in butter. Simply dressed arugula. Diced mango and berries in fruit coulis. The plate is a vision of generosity, but younger guests accustomed to choosing (and paying separately for) sides that catch their eye might prefer more choice – and more creativity.

There’s nothing wrong with doing what you know – even if you’ve been doing it a for long time – or in finding inspiration in others. Chefs have always stood on the backs of giants, tasting, learning, mimicking, exploring. To assume that we must always be moving forward, making progress, pushing boundaries, is not only very right now, it’s very American. Other cultures with more reverence for the past don’t put such expectations on their chefs. Yet at this point in his career, as Cerny rediscovers his passion for cooking, it’s hard not to root for more. I’d love to see him turn his lifetime of experiences – cooking with the top chefs in the world, building and losing a restaurant empire – into something new, something that only Radek Cerny, Czech émigré and longtime chef, could give us. Something with a Czech accent, perhaps? “Czech food is really heavy,” he responds dismissively. I laugh, thinking he’s deadpanning, because of course French food is heavy. He doesn’t.

Duck you: The What an Election! dessert.

Danielle Lirette

The tables around us did laugh, however, when we got to dessert, which is one place where Cerny freely unleashes his originality. Not on the burnt-cream Angelina, a thin variation of crème brûlée, but on the most expensive dessert you’ve likely ever ordered. For $25, you get two ducks, cast in chocolate and filled with lemon curd, marching on a plate like Easter bunnies escaping from children’s baskets. Some guests might want to simply relish the treat (and the fact that a restaurant has served something other than ice cream and bread pudding), spooning it up with orange-zested ice cream, meticulously sliced fresh fruit, crème anglaise and Chantilly. But others might find catharsis in smacking the ducks with a meat tenderizer, releasing lemon curd, shards of chocolate and some political steam. After all, consider the dish’s menu description: “What an election! Donald ducks marching to Washington.”

We tend to think of the past as stodgy, when in fact it was often just as free-flying, revolutionary and tradition-be-damned as the future we’re currently creating. At Atelier by Radex, you get a taste of the decades that paved the way for today’s earnest food scene, in a white-tablecloth, candlelit environment that makes you as nostalgic for what we’ve lost as for what we’ve gained.

Atelier by Radex, 2011 East 17th Avenue, 720-379-5556, atelierbyradex.com.

Hours: 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. and 5 to 9 p.m. Monday through Thursday, 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. and 5 to 10 p.m. Friday, 5 to 10 p.m. Saturday

Select menu items

(these are weekday prices; on weekends, all appetizers are $16 and entrees either $26 or $32)

Raviolis de homard $14

Panier de diables $16

Moules curry rouge $15

Saltimbocca ibérico $25

Cassoulet d’agneau $29

Le homard TV dinner $26

What an Election! dessert $25