Ball Corporation

Audio By Carbonatix

In late October, the Kroenke family, owners of the Pepsi Center, the Denver Nuggets and the Colorado Avalanche, surprised sports fans by revealing that they were changing the name of the 21-year-old Pepsi Center to Ball Arena. Ball Corp., the Broomfield-based aluminum packaging maker behind the name, is also expected to begin converting all of the drinking vessels sold at the arena – along with Kroenke’s venues in Los Angeles and London – into aluminum for an infinite recycling loop that should be in place by 2022.

The name drew some giggles, some raised eyebrows and plenty of questions. Who is Ball? An aerospace corporation? A Mason jar brand? Yes, and no. Ball does own the spacecraft parts and defense firm Ball Aerospace, but it no longer owns the iconic Mason jar supplier. Ball is actually the world’s largest aluminum packaging producer, supplying billions of containers from one hundred plants around the world to customers who make beer, soda, energy drinks, tea, kombucha, wine, cocktails, sparkling water and hard seltzer.

But it could be argued that this billion-dollar deal with Kroenke, one that will launch Ball’s name further into the public eye, came about in large part thanks to beer – and even more so because of a pair of Colorado beer makers: the iconic Coors brewing company in Golden and relative upstart Oskar Blues Brewing in Longmont.

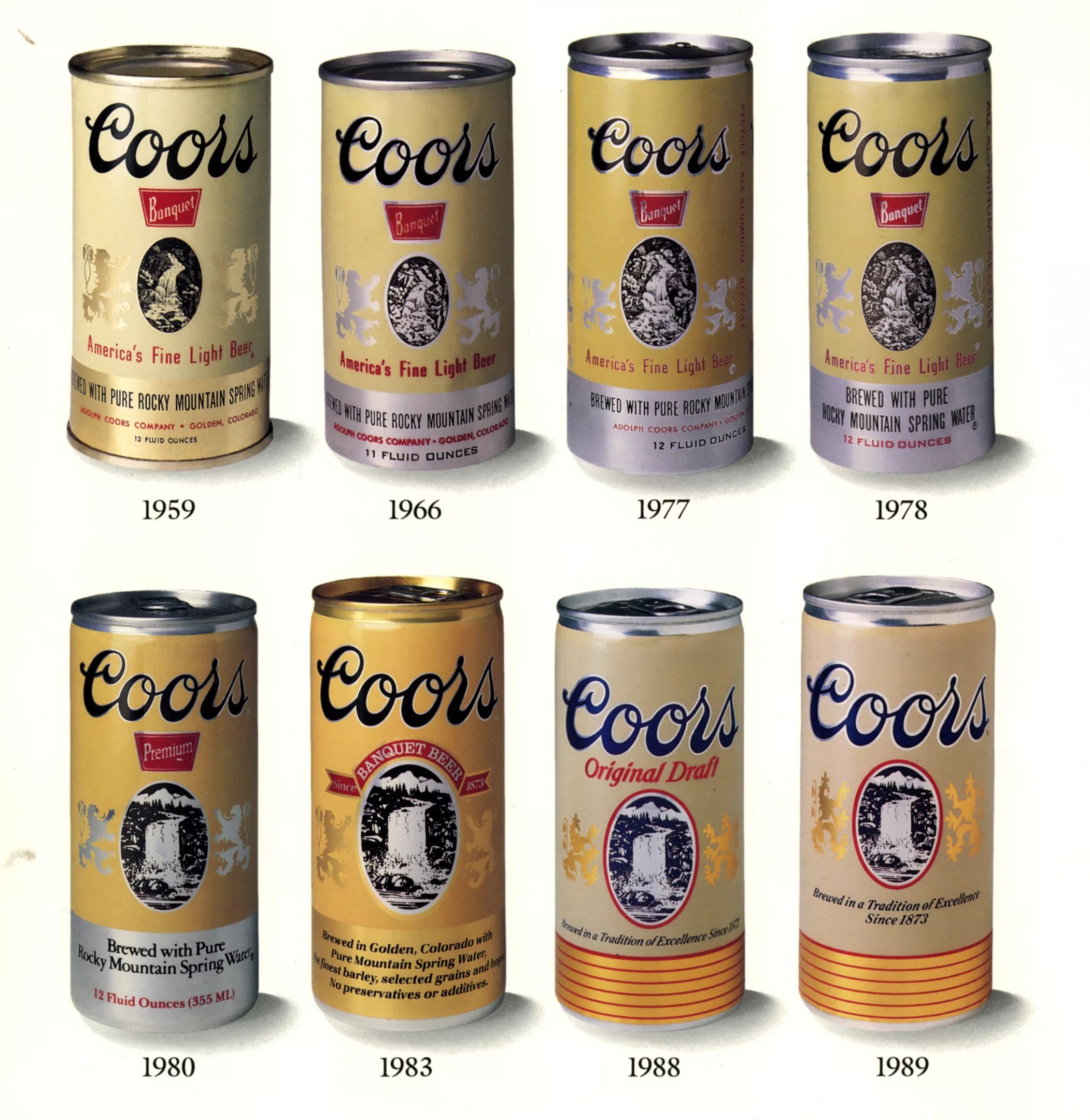

Coors and, more specifically, Bill Coors, pioneered the seamless two-piece aluminum beer can (now the industry standard) in the 1950s and created a can manufacturing company in Golden that Ball would later buy. Forty years later, Oskar Blues became the first craft brewery in the United States to embrace cans – a move that helped spread the recyclable message of aluminum to thousands of other breweries around the world.

Ball Corp. manufactures more than 100 billion cans each year.

Ball Corp.

These days, the topic of aluminum is causing anxiety among the nation’s 8,400 breweries and other beverage makers who use cans because of a steep increase in demand this year that created a production capacity shortage, which in turn left the country short by about ten billion cans. The reason, of course, is the coronavirus pandemic, which has changed consumer habits: Instead of drinking in public at breweries, wineries, bars and restaurants, customers are taking their booze to go or buying it in liquor stores.

“There is unprecedented demand for aluminum beverage packaging. … Ball can sell every can we make,” says Ball Corp. spokesman Scott McCarty, who has had a busy 2020 so far.

John Hayes, the CEO of Ball Corp., told CNBC recently that demand spiked by 24 percent in March and has increased by double digits each month since then. And that is on top of the already strong trend toward aluminum, which went from one third of all beverage containers in 2014 to more than two thirds now.

But the company is working to fix the capacity shortage by building two new factories, one in Glendale, Arizona, that should open in early 2021, and one in Pittston, Pennsylvania, that should open in mid-2021. In addition, McCarty says Ball has added new lines in its existing plants in Fort Worth, Texas, and Rome, Georgia.

So by the time capacity crowds are (maybe? hopefully?) eventually allowed back into Ball Arena next year for Nuggets and Avalanche games, concerts and other events, there will be plenty of aluminum cans available – and Ball will be able to focus on its recycling marketing message and its ties to Colorado.

MolsonCoorsBlog.com

The Story of Coors and Ball

When the late Bill Coors was asked in 2012 about the history of the recyclable aluminum can in Colorado, he chuckled a bit and, as Coors loved to do, he told a story.

“The can industry had terrible labor problems. They would have a strike about once a year,” he told Robert Budway, the president of the Can Manufacturers Institute, in a recorded video.

So Bill, who was a notorious hater of labor unions, asked his supplier if it would lease one of its plants to Coors so he could staff it with his own employees and prevent stoppages that would threaten his can supply. When the answer was no, Bill, who was Coors’s chairman from 1959 to 2000, took matters into his own hands, teaming up with a small can manufacturer in 1961 to create a Golden subsidiary, called JeffCo Manufacturing, that would exclusively work with Coors.

At the time, all the big beer companies were all using steel (or tin) cans, but Bill, who was an engineer by training, wasn’t happy with that, either: steel was heavy and expensive, and it imparted a bad taste into the beer, he thought. Not only that, but people were simply tossing them into rivers or onto the sides of roads, creating an ugly mess and public-relations problem for Coors.

Aluminum, he realized, could solve all of those problems at once. Not only was it lighter than steel, but seamless cans could be filled in a more sterile way, so Coors wouldn’t have to pasteurize its beer – something Bill disliked because he felt that pasteurization killed off the beer’s fresh taste. Aluminum could also be recycled, so people could bring cans back to the brewery for a few cents apiece instead of throwing them away.

Bill Coors.

MolsonCoorsBlog.com

So Bill created a pilot project to design aluminum cans, and in the mid-1960s, JeffCo Manufacturing converted its plant from tin to aluminum. By the end of the decade, the entire industry had switched to aluminum as well. In 1969, Ball Corp. (which was founded in Indiana in the 1880s as a glass jar maker) decided to get into the business by purchasing JeffCo as its first aluminum can manufacturing facility.

Today, Ball is a $12 billion multinational corporation, but it still has two plants in Golden. One is a joint venture with Coors called Rocky Mountain Metal Container (which only makes cans for Coors). The other cranks out aluminum vessels for hundreds of other beverage companies, including the majority of the country’s packaging craft breweries. Although Ball’s McCarty says the company doesn’t provide information “on how much is used by specific customer categories,” he does acknowledge that “Ball serves the majority of craft brewers either directly or by supplying cans to smaller mobile canners who can support very small production runs.”

One of those large customers is Oskar Blues, which resells cans to other beer makers. Another is Calgary, Canada-based Cask Global Canning Solutions, which supplies hundreds of thousands of cans to craft breweries around the world, along with its state-of-the-art canning machines.

In fact, it was Cask that hooked Oskar Blues on aluminum in the first place.

Cask Global Canning Solutions

The Story of Ball and Oskar Blues

By the late 1990s, aluminum was the purview of the big beer brands: Coors, Miller, Bud, Stroh’s, Old Milwaukee, Schlitz. The nascent craft-beer industry, meanwhile, differentiated itself by selling bigger, tastier – and more expensive- beer in bottles. So when Canada’s Cask Brewing Systems began pitching small breweries on the idea of canning in 2002, they all laughed.

Dale Katechis laughed, too. But the owner of Oskar Blues Grill & Brew, in the tiny town of Lyons, appreciated a good joke – and he knew a good gimmick when he saw one. Katechis bought a small canning machine (it sat on a tabletop and was operated by hand) and began putting his flagship beer, Dale’s Pale Ale, into aluminum. He was followed by Durango’s Ska Brewing, and then by a handful of other craft breweries around the country.

It turned out that Cask’s sales pitch had been on the money, since aluminum is cheaper, lighter, more portable, better at protecting beer from the damaging effects of light, and more recyclable than glass. “We created an affordable way for people to get into small volumes with packaging,” explains Russell Love, the president of Cask and son of Cask founder Peter Love. That’s because Cask not only provided the machines, but the cans, which it bought in bulk and then sold in small quantities to Oskar Blues, 21st Amendment Brewing, Flying Dog and others.

And Cask bought those cans from Ball Corp.

Peter Love (far left) and Russell Love (far right) at Tivoli Brewing in Denver.

Cask Global Canning Solutions

Adoption of the can came in fits and spurts. Some other Colorado breweries, like New Belgium and Breckenridge, got in early. Others, like Odell and Left Hand, acquiesced much later. But every time a small brewery began canning, it pushed the same message from a grassroots level: cheap, light, opaque, better for outdoor activities and infinitely recyclable.

“We have been banging that drum and sending that message for twenty years, and for the first ten years, no one really listened,” Love continues. “A few, like Flying Dog and 21st Amendment, and Dale – they slowly got that message out to consumers who believed that a canned beer was a cheap beer.”

Today, Cask buys more than 100,000,000 cans a year from Ball and resells them to several hundred craft breweries around the world, along with canning machines. “By and large, our average customer is just a few thousand barrels per year,” Love says. Oskar Blues, meanwhile, grew by leaps and bounds and now heads up the aptly named Canarchy Collective, a consortium of seven craft breweries that together make up the seventeenth-largest brewery in the country – and all seven buy their cans directly from Ball.

Cask and Oskar Blues “took the stigma away from cans and made it acceptable for other smart small-batch, and mega-batch, beverage makers to embrace the increasingly cool can,” adds Marty Jones, who helped popularize the can for Oskar Blues in the early 2000s and who now works with Cask. “While craft beer in brown glass bottles was first to get replaced with Ball cans, now it’s plastic water bottles that are being replaced with those mighty cans. And green wine bottles. And cold-brewed coffee bottles, cider bottles and glass growlers.

“Does that happen,” he asks, “without Cask taking the risk twenty years ago and carrying out its rule-busting efforts? Nope.”