Mark Andresen

Audio By Carbonatix

The story of how John Hickenlooper and his merry band of beer lovers opened the Wynkoop Brewing Company in October 1988 is now legendary. They put a new concept into an old warehouse in a dilapidated part of Denver and created an industry that made Colorado famous around the world.

But that story almost belonged to someone else.

In the latter part of 1987, around the same time that Hickenlooper was collecting furniture, used toilets, brewing equipment and wary investors for the Wynkoop, a Chicago-born businessman named Joe Benetka was also raising money for a restaurant and brewery.

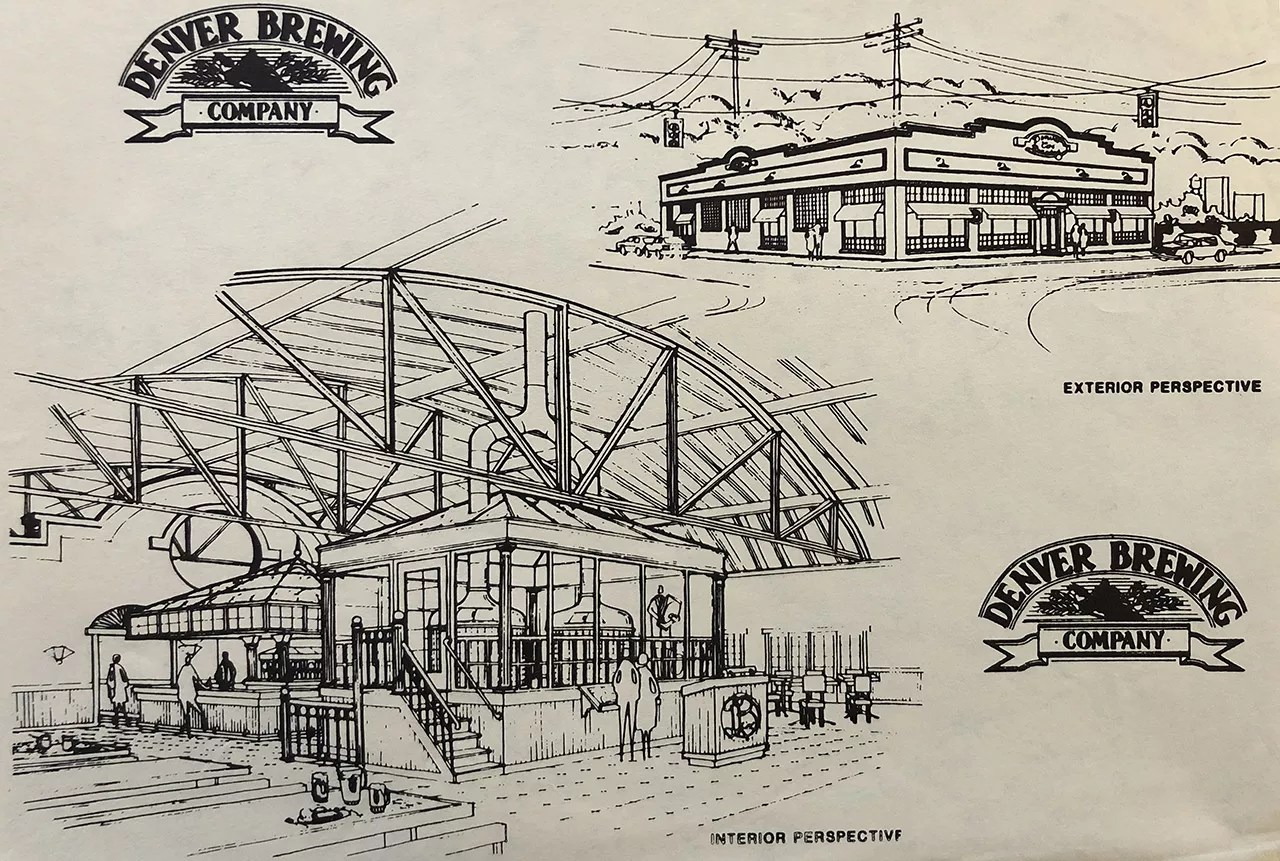

Benetka and his next-door neighbor, Bart Bonsall, had incorporated as Denver Brewing Company and secured a huge brick building at the corner of 15th and Platte streets, where they planned to open by year’s end. The pub would serve burgers, barbecue, pizza and sausage, and feature German- and Czech-style lagers made right there, where people could watch the brewmaster making the beer.

“We were trying to raise $1.5 million to really do it right,” Benetka recalls. Drawings of the project show dozens of tables and beer garden-style benches loaded with mugs and pitchers under a high barrel ceiling; in the middle are copper brewing kettles on a raised platform. In the back is a banquet hall for weddings, parties and other big events.

There was one major hitch to their plans, though: Colorado law wasn’t clear on whether restaurants could operate breweries and sell beer directly to the public without going through a third-party wholesaler, an arrangement that had been in place since shortly after Prohibition ended. And even if they could, breweries weren’t legally allowed to sell wine and spirits – something that would be crucial for most restaurants from a revenue perspective.

To make Denver Brewing Company work, then, Benetka and Bonsall would need to change the law, and neither of them had any experience in either lobbying or Colorado politics. But just eight months later, they had sealed the deal with handshakes all around from then-Governor Roy Romer.

That would be the final hurrah for Denver Brewing Company. But while Benetka and Bonsall were never able to raise the money they needed to open, the work they did in the Colorado Legislature paved the way for the Wynkoop, for the creation of a standalone brewpub license a decade later, and for the entire industry that followed.

Joe Benetka was born in 1941 at home on Chicago’s West Side, and grew up in the Cicero and Berwyn neighborhoods, which had been founded by Czech immigrants who’d left Eastern Europe a century earlier to escape political and religious persecution.

“As a kid, I remember there was a tavern on every corner – literally, on every corner,” he says. “They were a meeting place. It was where you socialized.”

Neighbors held their weddings in the taverns, with polka bands and food and beer. Always beer. “You think of blue-collar workers. They would work their shift, and then they would walk home or take a bus, and there was always a stopping place where they would go and get a beer,” Benetka says.

In the late ’40s, Benetka and his friends collected bottle caps, and they would ride their bikes around to each tavern and ask the barkeeps for them. “You could just smell the beer on the floors in those places, from all those years of being spilled,” he remembers.

That community feel was a hallmark of German and Czech culture, in which taverns weren’t just bars. They were social centers that provided the comfort of connection.

That’s the kind of feeling that Benetka wanted to re-create forty years later in Denver, where he’d moved in the mid-1970s for work opportunities.

“If they could open a brewpub out there in Chicago, why couldn’t we have one here in Colorado?”

He’d gotten the idea of opening a brewpub from his longtime friends Ron and Bill Siebel, the fourth-generation leaders of the Siebel Institute, a famed Chicago beer-brewing school going back to the 1870s that has trained thousands of brewers. The brothers were also co-founders of Sieben’s River North, the first modern brewpub and biergarten in Chicago, which opened in 1987. Benetka was an investor.

“I thought that if they could open a brewpub out there in Chicago,” he says, “why couldn’t we have one here in Colorado?”

He and Bonsall started putting together a business plan. They gathered information from Sieben’s (the Siebel brothers had agreed to invest with Benetka and Bonsall) and a handful of other brewpubs around the country. They priced out the cost of brewing ingredients, equipment and menu items.

Then they started researching the laws. “It turns out they were sort of restrictive,” Benetka says. So the two men registered as lobbyists, put together an outline of what they wanted to change, and headed over to the Colorado State Capitol.

“We didn’t have any political experience or background, but in those days, you could just walk right into the Capitol, start moving down the halls and meet people,” Benetka recalls. They eventually found lawmakers in both the House (Margaret Masson) and Senate (Don Sandoval) who agreed to sponsor an amendment to the state liquor code that would explicitly allow restaurants to have on-site breweries and to sell wine and spirits.

After that, they needed to talk to the big breweries – Coors and Anheuser-Busch – and to the beer wholesalers, who could easily have objected to a brewery selling directly to the public, since it was their job to be the middleman between brewers and restaurants and bars. But the wholesalers didn’t object as long as every restaurant that operated a brewpub actually made the beer on site.

“We went before the Senate committee, where the vote was 5-0 in favor, and the House committee, where it was 11-0,” Benetka says. Their proposal was eventually approved by both houses and sent to Romer, who signed it later that year.

Joe Benetka (from left), Don Sandoval, Governor Roy Romer, Margaret Masson and Bart Bonsall were all there when brewpub law was made in 1988.

Courtesy of Joe Benetka

When Hickenlooper and his team first heard about Denver Brewing Company, they had been working on plans for their own brewpub for about a year.

“They made us full of anxiety,” Hickenlooper remembers.

Hickenlooper’s group – which included business partner Jerry Williams, chef Mark Schiffler, head brewer Russell Schehrer and Schehrer’s wife, Barbara Macfarlane, among others – had looked at a couple of locations, including the former “Pony Express” building at 2363 Blake Street. They eventually landed in the J.S. Brown Mercantile Building at 18th and Wynkoop streets, thanks to the generosity of Jack Barton, who’d founded Kacey Fine Furniture in the 1950s and had used the historic brick building as a warehouse before deciding to take a risk on the young brewers.

It was then-Rocky Mountain News business editor Lynde McCormick who told Hickenlooper that a rival brewpub was in the works for Denver.

“He and I were in a book club together, and he’d been wanting to write a story on us forever,” Hickenlooper says. But the Wynkoop was taking longer than expected, so Hickenlooper had been putting him off. One morning, though, McCormick got a phone call from Benetka, pitching a story on Denver Brewing Company.

“John always did things on the cheap. But that’s okay — it worked for him, and that’s what matters.”

With that, the game was up. McCormick told Hickenlooper that it was now or never, and that the story, to be written by another reporter, would include both would-be breweries. In the end, the Wynkoop got more play, with a photo above the fold. The April 5, 1988, “special report” was called “Brewing up a Storm,” and it introduced Denver to “brew pubs,” an idea so novel that the words were in quotes.

“They were as ready as we were. In fact, they were further down the road than us,” Hickenlooper says of Denver Brewing Company. But the way the News story was presented, the Wynkoop looked like it was on top, which eased investors’ jitters. “That was just fate,” Hickenlooper says, adding that if the Denver Post had run a story instead of the News, “no one would have known about us.”

But by October, the Wynkoop was ready to go, while Denver Brewing Company was still searching for enough investors to break escrow. While Benetka and Bonsall were hoping to raise $1.5 million, Hickenlooper and company had done what they needed to do with just $575,000, including a $125,000 loan from the city, a $150,000 bank loan, and a last-minute, life-saving $20,000 that Barton kicked in.

Barton, who passed away in January at the age of 96, also gave the Wynkoop the now-legendary lease rate of $1 per square foot.

That wasn’t a deal that was easy to come by – certainly not for Benetka, who was keenly aware of the ways that Hickenlooper managed to hustle. “John always did things on the cheap,” he says. “But that’s okay – it worked for him, and that’s what matters.”

The Denver Brewing Company had plans to build the city’s first brewpub a mile from the Wynkoop location.

Courtesy of Joe Benetka

While the Wynkoop opened in economically depressed Denver to an enormous amount of fanfare, Benetka and Bonsall continued to work on Denver Brewing Company. In 1989, Benetka bought the building at 15th and Platte in hopes of making the process easier.

But although they had some investors, they weren’t able to find enough. “I just couldn’t shake the money tree,” Benetka says. “People kept saying Denver didn’t need another restaurant.”

Scott Smith understands the challenges they faced. “Very few people were familiar with the concept of a brewpub back then. If you had been to California or Oregon, you might have seen one. But when we said what we were going to do, they said, “A what? What is a brewpub?”

Smith, who managed the Old Chicago in Fort Collins, had seen one – and he’d been working on a plan to open his own brewpub in Fort Collins, Coopersmith’s Pub & Brewing, when he bumped into Wynkoop partner Schiffler at a food-service equipment auction in the summer of 1988. Schiffler told Smith about the Wynkoop plans, and also that the law was about to change to allow brewpubs to serve wine and spirits. He gave Hickenlooper’s number to Smith and told him to “call John.”

John Hickenlooper is now a candidate for U.S. Senate.

“John and I sketched out a deal on a cocktail napkin,” Smith says, and the result was a partnership that opened Coopersmith’s in October 1989, a year after the Wynkoop debuted. “I knew there was a market for craft beer that wasn’t being filled, and I knew it would work, having seen other brewpubs that were successful in other parts of the country,” Smith says.

“I wasn’t worried about someone else opening another brewpub in town. I figured that if there was room for another restaurant, there was room for another brewpub.”

That turned out to be the case in Denver, as well, despite all the troubles that Benetka had encountered. The next was Rock Bottom Brewery, which opened in the base of the Prudential Building in 1991. It was owned by Frank Day, a restaurant entrepreneur who had created the Old Chicago chain in 1976 and opened the Walnut Brewery in Boulder in 1990.

Then came Champion Brewing, a sports-themed brewpub in Larimer Square, and Breckenridge Brewery, which opened a Denver outpost at 22nd and Blake streets.

The rest of the state was also seeing a surge of brewpubs. Within just a few years, Boulder, Vail, Crested Butte, Colorado Springs and a number of other towns would also have brewpubs to call their own.

But after several more years of trying, Benetka and Bonsall eventually gave up on Denver Brewing. “We had to face reality,” Benetka says.

In 1995, he leased his building at 2375 15th Street to the owners of Shakespeare’s Pub & Billiards, which would hold down the corner for a decade. When Shakespeare’s moved out, Vitamin Cottage Natural Grocers took over the spot, where it stayed until 2014, when Benetka finally sold it to a development company. It has since been torn down and replaced with a five-story office building.

A few years ago, Benetka took his two grown children to the Czech Republic to see Prague and visit the small towns where their ancestors had lived. Later, his daughter, Ali, decided to attend Siebel Institute, earning her certificate and eventually taking a job at Left Hand Brewing in Longmont. From there, she moved on to Denver’s Renegade Brewing, becoming only the second female head brewer in Colorado. She later worked in a similar capacity at Ratio Beerworks before moving on to Crafted ERP, a brewery software company.

While Benetka knows that Ali probably won’t choose to open her own brewery, he keeps renewing his registration of the Denver Brewery name with the Colorado Secretary of State’s Office.

“We had all the dreams,” he says. “All I have now are pictures and drawings and memories.”

Still, he adds, “I have no regrets.”

And he shouldn’t. In 1996, Colorado’s liquor code was changed again, this time to create a standalone license for brewpubs that completed the changes for which Benetka and Bonsall had fought. That license has allowed dozens of companies to go into business, contributing to Colorado’s craft-beer community.

“It was Joe and Bart who did that,” says Hickenlooper. “They did the work.”

Jonathan Shikes is the author of Denver Beer: A History of Mile High Brewing, which was released in March 2020. The book explores the past and present of the city’s favorite beverage, from 1859 to 2019. It is available online at the Tattered Cover, BookBar, Barnes & Noble and Amazon.