Bonanno Concepts

Audio By Carbonatix

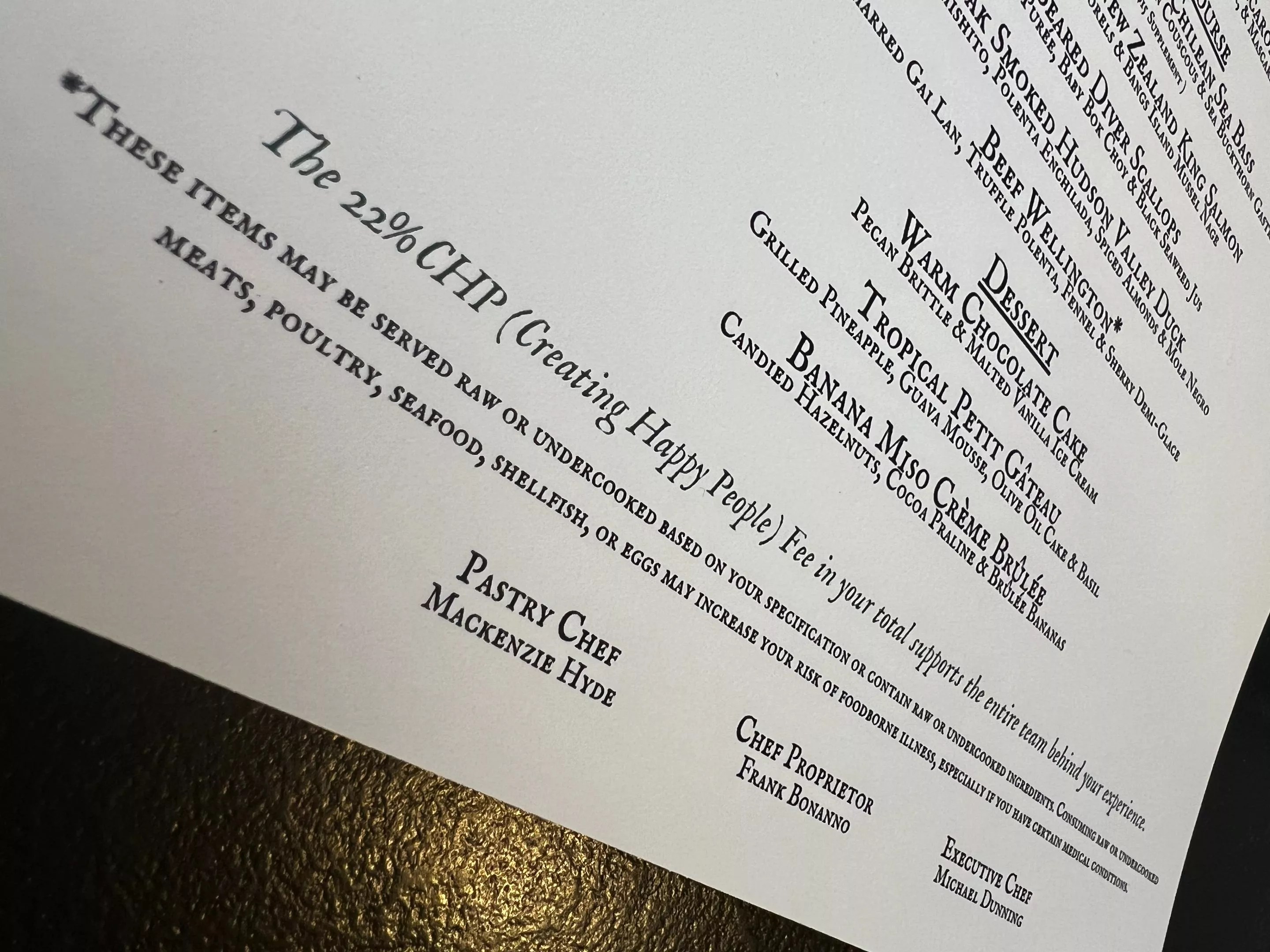

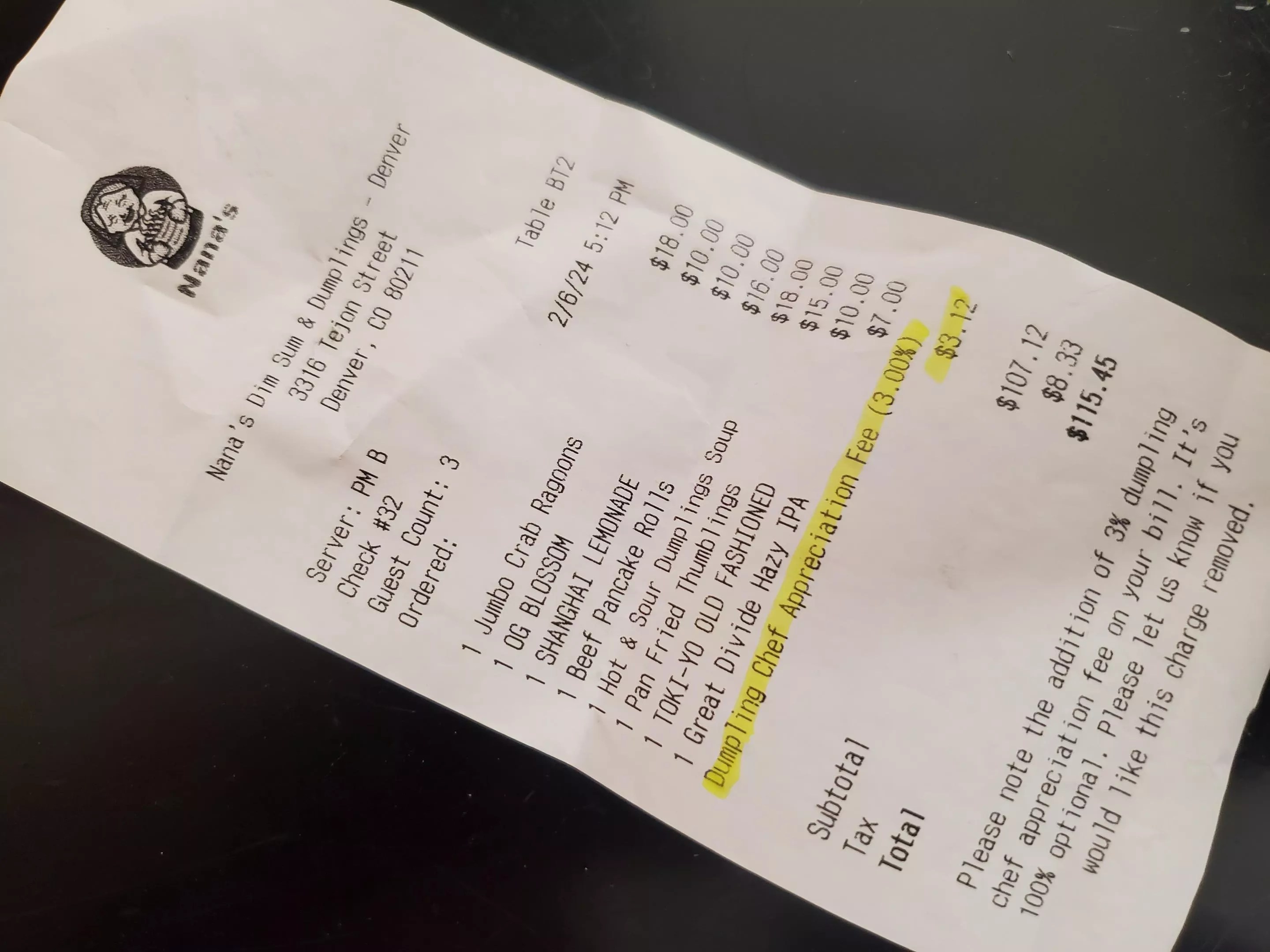

Whether it’s the 3 percent Dumpling Chef Appreciation Fee at Nana’s Dim Sum & Dumplings, the 4 percent Wellness Fee at Bodega, or the 22 percent Creating Happy People fee at Bonanno Concepts restaurants, surcharges of all kinds are a common addition to restaurant receipts these days. A lot of diners hate them; even more don’t understand them.

The proliferation of service charges even prompted one Reddit user to create a public Google Sheet listing every fee at local restaurants – most recently updated in February, it currently has 432 entries.

If diners are confused, the path isn’t much clearer for restaurateurs. Navigating how service charges and tip structures affect the bottom line is complex, as illustrated by this breakdown from the Colorado Restaurant Association.

One factor driving the increase in fees is the rising minimum wage – particularly at restaurants that operate within Denver, which has the eighth-highest minimum wage in the country at $18.29. In Colorado, restaurant owners also have the option to take a $3.02 tip credit, giving them a little more flexibility because the minimum wage for tipped workers in Denver is $15.27. But employee pay is just one of the considerations on their plate.

Most restaurant fees fall into three categories. Some, like Bodega’s, are a small percentage used for a specific employee benefit separate from wages. Others, like the one at Nana’s (which is optional, according to the message at the bottom of its receipt), are a small percentage that does supplement wages, usually in a way aimed at solving the equitability problem.

Fees, fees everywhere.

Molly Martin

The type that’s gotten the most blowback from the public is the 20 percent (or higher) service charge that is automatically added to a guest’s total bill, which replaces the standard U.S. model that leaves the choice of how much to tip – or whether to leave a tip at all – in the hands of the consumers.

In recent years, some stories have traced the modern tipping culture back to slavery, an origin often referenced by people who wonder why restaurants don’t just pay staff a living wage without needing tips as a supplement. But other stories point out that some employees earn far more with tips than they would with a salary.

Challenging the tipping status quo in America isn’t a new development. Over a decade ago, Eater Denver asked a group of local chefs and owners if the tipping system should, and could, change in response to a column by New York Times restaurant critic Pete Wells that garnered a lot of opinions titled “Leaving a Tip: A Custom in Need of Changing?”

There was no consensus then, and there doesn’t seem to be one now.

But there’s definitely plenty of confusion. Why not just raise prices? Where do these fees go? Questions abound, so we sought answers from three of the metro area’s biggest names in hospitality.

Frank and Jacqueline Bonanno run Bonanno Concepts.

Bonanno Concepts

Bonanno Concepts

Frank Bonanno has been a chef and owner of restaurants in Denver for decades. Currently, Bonanno Concepts has around 250 employees spread between Mizuna, Luca, Salita, Osteria Marco, Salt & Grinder, French 75, El Rancho and Vesper Lounge – the only spot that doesn’t charge the 22 percent Creating Happy People (CHP) fee, which was introduced as the Bonanno restaurants reopened following the pandemic-era shutdowns.

While dining rooms were closed, “we had time to analyze what servers made,” Frank explains. “What we wanted to look at is, how do we keep the servers making the same, if not more, money and get our back-of-the-house to make more money? We decided that we would just put a fee on the bill and say that tipping is now really optional – you don’t have to tip. It’s nice if you do. If you have a great experience, that’s great, and that tip goes 100 percent to the front of the house.”

But the fee is also intended to make pay more equitable among front-of-house staff. “You need servers to open for lunch. That’s not the most lucrative period. You need servers to work the back station that may only get five tables and end up running food for the station that’s the busiest,” Frank points out. “What we thought is that we would really like to see a more team environment going on. There is no shitty section in our restaurants right now because everybody is paid equitably.”

The fee is communicated on menus, websites and verbally, but there is still a tip line on the receipts because diners do often want to add extra, the Bonannos say. The group’s training instructs staff to communicate that “we are a tipless house,” notes Jacqueline Bonanno, Frank’s wife and business partner. “We feel like we have taught this a million times, but it is like teaching middle school. Every year a new class comes in and you teach the same materials over and over again. …That’s probably where we fall short that we try really fucking hard to get right, is that we have to be training every week at lineup. Every time there’s a new hire, they need to be immersed in practicing their language and getting a comfortable rhythm down. It’s just challenging.”

Why not just raise menu prices?

“Raising menu prices for us by 22 percent and paying a guaranteed wage would be ideal, but what do you do in January when we just dip and everything is so slow,” Frank asks. Or even at the start of the week when there are fewer guests? “Then you’re just cutting servers and no one is making money. This system allows us to keep servers, and when it’s slow, everybody makes some money. And it can’t be a set $48 an hour, because then the restaurant would be out of money.”

Plus, he adds, “Then you’re talking about Margherita pizzas being $28.”

Mizuna is one of Frank Bonanno’s more high-end concepts.

Courtesy of Bonanno Concepts

How is the fee used?

According to Jacqueline, here’s how the fee is currently broken down: “On a $100 ticket, a guest pays $22; $18 goes directly to staff, $2 goes to employee health insurance, $1 goes to transportation (RTD passes), and $1 goes to unemployment insurance and workman’s comp (this is actually $2, but we supplement that extra dollar). Our books are transparent and the numbers are well documented. There’s a line item for CHP on all paychecks, and a book that tracks what we collect and distribute in every manager’s office for employees to review.”

She adds that since the launch of CHP, “the pay gap closed by nearly 60 percent, but wages have gone up nearly across the board.”

The distribution of the part of the fee that goes to staff varies by restaurant. “At Mizuna, for example, the kitchen is run by truly culinary-trained, academically-trained chefs and they deserve a bigger proportion of the split, whereas Osteria is less touch, less technical skills or speed, and so the breakdown changes a little bit. … Every quarter we revisit it and see if it’s fair,” Jacqueline explains.

For servers, not getting the full 22 percent fee isn’t much different than the way traditional tips were distributed, Frank notes. “People always think if I give a server $20, they get to keep that $20. … In almost every restaurant, that server was still tipping out the bar 3 to 4 percent, 1 or 2 percent to food runners, 1 or 2 percent to bussers and in recent years, you could tip out the host 1 percent.” In addition, the average tip was lower, around 17 to 18 percent. “We took all of that data and figured out what servers were truly walking with,” Frank says.

What has the response been?

“Online reviews are mixed,” Jacqueline admits. “The thing with the CHP is, overwhelmingly we are complimented on it. We are thanked for it. People love the pressure of tipping being taken off their plate. But the people who love it would never go online and compliment it. It’s only going to be the people that don’t like it who are going to go online and complain about it.”

As for staff, “When we started this, we lost almost all the employees at Osteria Marco,” Frank says – though it didn’t have many at the time, as it was just ramping up and rehiring after the long, mandated closure. The fee-in-place-of-a-tip model is often unappealing to front-of-house staffers who feel like it forces them to share – especially for more experienced employees, who are used to pulling in a higher average tip than their co-workers.

“We appreciate everybody’s personality and we appreciate everybody’s individuality and some people are better than others, but you do need a team to run a restaurant, and you need the kitchen to run a restaurant,” Frank notes. “We’ve been doing this four years now, and the [staffers] that buy into understand it. It takes math and it takes you realizing that, I know exactly what I’m going to make in a shift. There is no good or bad station. … We can tell you at any of our restaurants what you’re going to make in a shift.”

Still, some former Bonanno employees have taken to online platforms to vent. “You show up to work three days in a row intoxicated and we had to let you go. Okay, you’re gonna go home and get on Reddit or Instagram or Facebook and say, ‘This is unfair, you never explained it,’ but the truth is you signed a piece of paper explaining exactly where everything went. … And we’re not gonna go on and say, we know who you are, this is why you were terminated. No one ever hears that side of the story,” Frank says. “Some people quit because they don’t like it and that’s their prerogative, but clearly there is a benefit. I’m not saying our system is perfect.”

“We’re revisiting it every quarter,” Jacqueline adds. “We look at it squarely in the face. We have the uncomfortable conversation. At some point, we may truly decide it’s not serving us. It’s not serving us emotionally, it’s not serving us financially. But right now, it is. It’s serving everyone, and it’s pretty great.”

Juan Padró’s restaurant group now implements a 20 percent service fee.

Esther Lee Leach

Culinary Creative Group

Juan Padró is the founder and CEO of Culinary Creative Group (CCG), which has grown rapidly since the pandemic. It now includes four Tap & Burger locations, two outposts of both Aviano and Mister Oso, A5 Steakhouse, Ash’Kara, Señor Bear, Fox and the Hen, Bar Dough, Red Tops Rendezvous, Ay Papi, Forget Me Not and Kumoya.

The group first experimented with adding a service fee in November 2019 at the original Tap & Burger in Highland. “We were just trying to dip our toes in the water and see how it worked,” Padró recalls. “It’s something that we had been talking about for a while because we saw this coming. Labor was just getting more expensive.”

Then there was “the absolutely ridiculous Denver City Council maneuver during COVID to tie the minimum wage to the [Consumer Price Index],” he continues. “Restaurants are on the brink in Denver. You’re already operating in an environment in 2020 where 3 to 5 percent was above average for a margin. Then you go and increase the minimum wage 67 percent in three years. There’s no scenario and no reasonable human being that thinks that’s something a business can absorb – especially a low-margin business. Unfortunately, we have some unreasonable human beings in leadership.”

While the concepts were coming back from the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, he adds, “we wanted to give our managers a little bit of leeway with how to distribute the fee, just because every store had different problems during COVID.”

But Padró notes that “this concept, this idea that COVID ended two years ago is just absolutely insane. The repercussions of COVID, we’re not even in the middle of it.”

Now, CCG has added a 20 percent service fee across the board, which is noted on its menus and on OpenTable where diners can see it before making a reservation. “The biggest challenge was the fact that this year, we decided that we needed more consistency across the brands, so that’s what we’re in the middle of right now,” he says.

The menu at A5 notes that it is “a service-included restaurant.”

A5 Steakhouse

The fee, he adds, is a step toward fixing a big problem that restaurants face. “This industry is so broken, it suppresses its A-talent at the hourly level, because your bartenders make more than your GMs. That materially is a flawed system, because it incentivizes C players to manage A players, and in what scenario in life does that work? What we need to do is create a path forward that incentivizes our best people to grow and allows them to stay in an industry they love.”

The service charge also alleviates the discriminatory nature of the traditional tipping system. “When you are living in an environment where tips are the majority of your income, there are some fundamental things that from a societal perspective are wrong,” Padró explains. “Number one, if you have dark skin, you get tipped less than if you have light skin.”

The unpredictable nature of tipping also means that employees who are often from vulnerable communities don’t have reliable income – or income that is verifiable, meaning it’s hard to get approved for a car loan or a mortgage. Affordable housing is a big challenge in Denver right now, and Padró believes that “we have more affordable housing than we think we do – if we verified income.”

On the flip side, “If you’re not claiming your tips and you’re showing $20,000 in income so you don’t have to pay taxes, is that really good for society?” Padró asks.

“So we said we’re gonna fucking rip all that out. The 20 percent service charge allows for equality, first and foremost,” he explains.

Why not just raise menu prices?

“In some cases, that may work,” Padró says. “At A5, I could increase my prices 20 percent and I don’t know that people would really give a shit. Same thing at Forget Me Not. But you tell me in Denver if somebody’s gonna go to a burger joint and pay $24 for a burger. I don’t think they are.”

He recalls a recent trip to L.A., which has done away with the tip credit, where there was a $34 burger on the menu: “L.A., that might work. If somebody feels like that’s going to work in Denver, then I want them to put the money up for the restaurant and I’ll happily operate it.”

Overall, though, that question about menu prices? “I hate to even be addressing it because it’s just flat-out ignorant,” Padró says. “You clearly have no clue what you’re talking about when you say that.”

Generally, the service fee at spots like A5 has been well received, Juan Padró notes.

A5 Steakhouse

How is the fee used?

Padró admits that “when you get into that conversation, it confuses people. In their mind, they’re looking at it like, ‘this is my tip.’ But it’s not a tip. That’s the distinction. The service charge is income that’s owned by the business. And the only thing that matters is that 100 percent in our company goes to payroll.”

CCG uses a tiered system to distribute the fee based on “job performance outside of sales,” Padró says, such as side work and menu knowledge. “The other component is the split between front and back of the house. This year, we decided to take the tip credit,” which is a change from recent years.

That means that “you have to true everybody up to minimum wage, then the point system kicks in,” he adds. Currently, 70 percent of the fee gets paid out weekly, with 72 percent of that going to front of the house and 28 percent going to back of the house, which has a similar tiered system.

While there is some fluxation in slower seasons, Padró says servers generally end up making $35 to $45 per hour.

The other 30 percent “is held in what we call reserve and that is used for other payroll-related expenses,” such as rewards for high-performing employees and a stipend for management. It also supports “anyone else that touches a store,” like the social media and marketing team.

Although the fee replaces the need to tip, CCG does still have a tip line on its receipts. “I think the fact that we leave the tip line in causes more confusion. But we do it because it allows our people to make more money,” Padró notes. Any tips that are left are pooled and distributed daily.

What has the response been?

“Typically, people don’t really blink or have an issue at an A5 or a Kumoya or Forget Me Not. In fact, they prefer that kind of thing – at least the guests do,” he says. At more casual spots like Tap & Burger or Mister Oso, he expected more pushback from the fee, but “generally speaking, it wasn’t as big of a deal as we anticipated.”

But Padró does note that some employees, particularly younger ones, “had a harder time understanding the whole concept of it. … The shift really needs to be in the mentality of tips vs. total income. Ultimately, the focus is on total income. Our data shows that people are making on average 19 percent more than they did when they were in a strictly tipped environment.” The retention rate remains high, too.

“Theoretically and philosophically, it’s really about closing the gap between front and back of the house,” Padró concludes. “Our dishwashers make $24 an hour for a stepping-stone job – that’s high. We need to get away from this idea, and city council touted this stuff – they loop McDonald’s and Fruition into the same conversation, which is fucking stupid. They’re not the same business.

“They talk about needing to give people a living wage. Is $18 a living wage in Denver? It’s not. So stop saying that. We need solutions to get people to wages that are $30-plus an hour. That doesn’t mean there’s not stepping-stone jobs to get there, but we need to get there, and that’s what this system allows us to do.”

Bobby Stuckey, partner and master sommelier of Frasca.

Frasca Hospitality Group

Frasca Hospitality

Last year, Bobby Stuckey was named one of the fifty most powerful people in American fine dining. He co-founded Frasca in Boulder twenty years ago and the group now also operates Pizzeria Alberico as well as Tavernetta and Sunday Vinyl in Denver.

It has always operated with a tip pool system and moved to a whole house tip share about four years ago, once that became legal in Colorado.

“There are going to be some restaurateurs who don’t like what I’m about to say,” Stuckey warns.”The whole gratuity thing in America is wonky already, but my job is not a legislator and I’m not writing federal policy to make it illegal. So then my job as a restaurateur and as a restaurant person is, what’s most transparent to two major people in my life: my guests and my employees,” Stuckey says. “There is no transparency with the service charge and I don’t think even the employees truly understand it.”

Another issue with a service charge is that “consumers like being in charge of tipping,” he adds. “It freaks me out. I don’t think it’s a good thing that that’s how their ego is. But it’s a fact of life.”

The move to a whole house tip pool also means that Frasca had to give up the tip credit and move to the higher minimum wage. “It costs us a lot of money to do that, but then the whole house gets to share in that gratuity,” Stuckey explains. “That was always a problem for me. … If you don’t share with the back of the house, that is really wage suppression for a major sector of the American workforce.”

Why not just raise menu prices?

The people who make that argument are “the same group of people complaining about how expensive dinner out is in Denver,” Stuckey says. “We had the highest restaurant expense inflation in America last year, but we don’t get the benefit of the concentration of revenue like a city like San Francisco, Chicago, New York or LA. … That’s the one-size-fits-all solution that diners don’t want to hear: it should cost a lot more money to eat out.

“Everything is against the restaurant. Everything. … Even how our cities look at us is wrong. We don’t charge enough, but it’s a very slippery slope. Consumers think they understand what we go through. Why don’t we just pay people what they should be paid? Of course, we want to, but our margins just aren’t there.”

How does the tip pool work?

“Everyone is paid the higher minimum wage and then there are certain points per position,” Stuckey explains. In the past, the point system “was broken,” with a standard number of points assigned to various titles. But that didn’t take into account each individual’s experience. Now “there’s more points, and there’s a lot of labor on management to organize what we call the point evaluation,” he says.

So a new hire trying out fine dining as a glass polisher, for example, benefits from the tip pool, but with a much lower cut than a long-term employee who is trained in multiple positions.

What has the response been?

When the Frasca group introduced whole house gratuity, “we lost a lot of employees because four years ago, the front-of-house people didn’t want to do that,” he admits. “There are some front-of-the-house servers that have this very mercenary idea – ‘I’m going to go where I can make the most money per shift.'” But since then, “we’ve seen them come back to us because there’s so many restaurants doing the service charge now.”

No matter how transparent a restaurant tries to be about how a service charge is being used, he adds, both guests and employees “are not going to believe you. … Until you just make gratuity illegal and everything just gets wrapped up into the price of the menu item, I think the most transparent thing is whole house gratuity.”

As a group with largely high-end, fine dining concepts, Frasca does have more flexibility to bake some of the additional labor costs into menu prices, which isn’t the case for all dining establishments.

So what’s the long-term solution?

“I think every restaurant has to choose their own path,” Stuckey says. “I see why these people are trying all these different service charges.”

Frank Bonanno agrees. “You can’t look at every restaurant the same,” he adds.

But Padró thinks that service charges like the one at CCG can, and should, become the standard. The smaller fees, he says, “are band-aids.” The same goes for tip pools. One Fair Wage is currently pushing for the tip credit to be eliminated, he notes, and “it’s a very real possibility that in the next few years, tipping is gone in America.”

In Washington, D.C., and Chicago, where that’s already happened, “the data isn’t looking good,” Padró notes. “If independent restaurants don’t unite and come up with a better system, that’s where we’re going.”