Martinez has seen many changes to school breakfasts and lunches over the years. Nutrition requirements and the rules for using fresh versus packaged ingredients have evolved, and over the past nineteenth months, Martinez’s staff has developed new ways to serve students during a pandemic. Now the team is adapting to the district’s new initiative to prepare more meals from scratch.

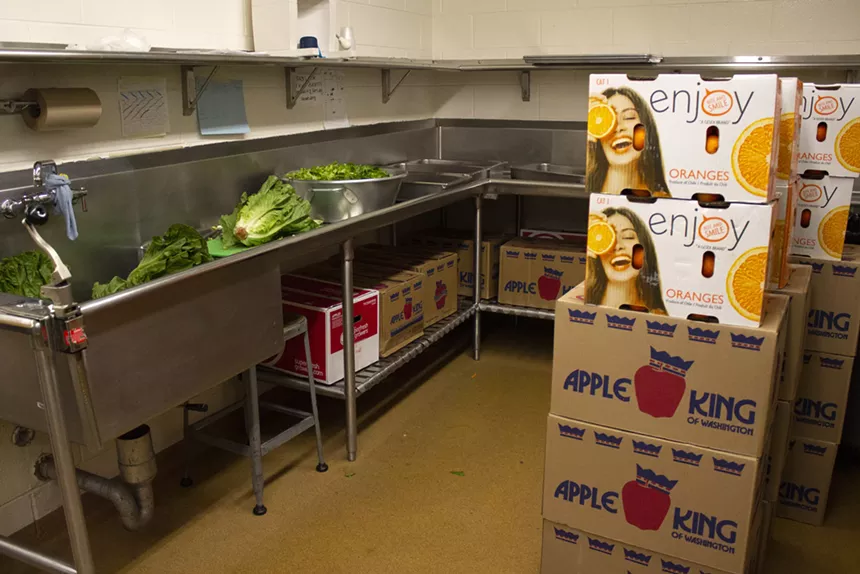

Back in 1991, Martinez’s first job in DPS kitchens was to prepare salads — washing and chopping bunches of lettuce and bags of carrots. She knew she could do more, but she’d recently moved to Colorado from Mexico and felt the language barrier got in the way. Eventually, though, she became a cook and started taking language courses offered by the district. By 1996, she’d finished the classes she needed to qualify for a higher-paying position.

“One of the requirements to be a manager is to have all the classes," Martinez recalls. “I wasn’t looking to be a manager.”

But she’s been a manager ever since, seeing school kitchens through many changes.

Over a decade ago, DPS made some changes to its food program as a result of labor shortages, explains Theresa Hafner, director of food and nutrition services, and switched to providing pre-packaged ingredients.

“If it’s pre-cooked, you don’t need two cooks,” notes Martinez. The kitchens started getting “ground beef in bags, pre-cooked turkeys ready to slice,” she recalls. Even the vegetables were cut and ready.

Martinez's first job in DPS kitchens was preparing salads...but the rules for that have changed, too.

Claire Duncombe

The push included a training program for DPS kitchen employees, Hafner says. The district offered classes ranging from how to work with yeast to how to make a salad bar look attractive.

Martinez remembers taking classes with chefs and teachers about cooking raw beef and preparing vegetables by hand. The ingredients were fresher, and the taste was better, she recalls. And the kids noticed.

“The smell comes out of whatever food you’re making, and that smell goes everywhere,” she adds. “The kids enjoy that. They already come with something, [thinking] ‘I’m going to eat what I was smelling.’ I think that’s the difference.”

Not all changes came from within. Hafner, who became director of food and nutrition services in 2011, says that the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2014 affected policy because of the revised nutrition requirements set up by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The USDA lowered the sodium content in school meals, for example, and added more whole grains, fruits and vegetables.

Hafner is currently overseeing a renewed DPS focus on creating school meals from scratch. The district aims to raise the percentage of meals made from scratch from 60 percent to 99 percent over the course of its three-year contract with Brigaid. The Connecticut-based company of professional chefs has been hired to teach staff new skills, such as knife techniques and exchanging herbs and spices for salt to boost flavor.

The pandemic has created a number of complications for DPS kitchens, but staff is continuing to prioritize feeding the students.

Claire Duncombe

“Feeding kids is so important,” she adds. “I’m a mom myself. If I feed my kids healthy food, they learn better, they stay healthier and their chances for success will be better."

For Martinez, her job is not just about meeting the nutrition standards. She also likes to cook what students want to eat.

She points out that Place Bridge Academy students, who come from many different countries, seem to like falafel more than students enrolled at other DPS schools. They also love rice and flatbread. “Every school is different,” she explains.

Currently, supply-chain shortages are affecting the availability of some of the food she typically orders, such as rice, tortillas and watermelon. As a result, Martinez and other staffers have to figure out substitutions that continue to meet nutrition requirements.

But during the pandemic, they’ve gotten accustomed to adapting. During the last months of the 2019-20 school year, Martinez and her staff were preparing 300 meals a day for pick-up by students in the parking lot or delivery by bus to apartment buildings. They’d make 600 meals on Fridays.

Martinez is confident that her staff will continue to successfully adapt and serve students after she retires and moves to Mexico with her husband. “I taught everybody to do everything,” she says. “Because everybody needs to learn, and not just make fruit or bread.”