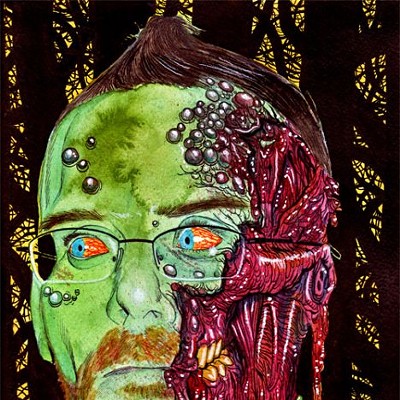

After tackling the life of a young Abraham Lincoln for his first graphic novel, Denver cartoonist Noah Van Sciver turned to a more accessible, but no less dramatic, subject for his follow-up: the modern American working class. In Saint Cole, Van Sciver explores the plight of the average man raising a family on a low-wage job, trying — and failing — to navigate a dysfunctional family, a dead-end career and an ever-growing reliance on drugs and booze to escape. Grim, gritty and depressingly true to life, the book is also strangely hopeful, thanks to one of the weirdest “happy endings” ever. Van Sciver is celebrating the release of St. Cole and the latest issue of his Blammo series — a special full-color compilation of some of his favorite stories that have appeared elsewhere — on Wednesday, February 18, at Kilgore Books. In anticipation of the event, we caught up with Van Sciver to talk about meeting his fans, the grind of working-class life and running a Kickstarter to pay for his funeral.

Westword: Do you like doing personal appearances? Is that fun, or more of a burden?

Noah Van Sciver: It depends. It’s like, sometimes I don’t want to see anybody. I don’t want to talk to anybody. Other times, I’m just lonely and I want to hang out. It depends. It’s an every-other-day thing. I basically have a two-month window between really dark depressions. It depends on how that lines up for me. Maybe I’ll just be sitting here quietly, crying or something. Hopefully not.

Is that dependent on the the crowd to some degree? I imagine it’s a different crowd at Kilgore than at something like Denver Comic Con, where it’s some random guy going, “Are there superheroes in this book?” I assume the Kilgore crowd is more aware of underground comics and maybe even familiar with your work, if only from Westword.

Yeah, for sure. [Laughs.] Yeah, they’re a little more open-minded than the Comic Con crowd is. Usually, in my experience, people who read superhero comics and are part of that world are pretty close-minded about any other kind of comic. If it’s not “flights and tights,” they’re just not interested. They’re looking for comics that help them escape reality, and my comics are normally about reality. They’re just like, “Ugh, I don’t want any of that. Reality has failed me.”

Your comics may not be the best thing for someone who’s looking for escapism, for sure.

Yeah, it’s fine. Everyone wants different things.

Your graphic novels definitely aren’t escapism. Your debut, The Hypo, was historical fiction based on Lincoln, and now Saint Cole is basically a serious, literary novel, just delivered in a graphic medium. The term graphic novel describes it precisely. It could have been invented to describe it.

Yeah, that’s true. I’m especially proud of [Saint Cole] because with The Hypo, it was basically all true stuff. I just had to cherry-pick different things that happened in Lincoln’s life to make that story. But Saint Cole is the first long fiction story I’ve ever written. I think I’m more proud of this one. I’m proud of The Hypo, too, but for different reasons.

Right, it’s very different to do a bunch of research to piece together the most interesting parts of a historical figure’s life into a coherent narrative than to pull on what I assume are real-life experiences, of your own or friends, and then synthesize that into an original narrative. And it’s a hell of a story. It was almost hard for me to read, because it was so true to life for so many people I know and grew up with.

Yeah, I hear that a lot — that it’s hard for people to read because it’s so bleak. I agree, it’s also the kind of people I grew up with. It’s [true] for a lot of people — it’s just the average person nowadays, or it feels like one in ten people are this guy. Everybody knows somebody like that.

Right. Most of us aren’t that guy, but we all know him — the guy who’s made some bad choices and had some bad luck and now is just fucked beyond belief.

It’s the struggle. Nowadays, people will have a kid and have a family but they don’t have the income to support that, so it’s just a constant grind to do what every other generation did. He’s expected to have a kid and have a girlfriend and all these responsibilities and he’s expected to take care of that with [a job at] a pizza restaurant. It’s not that much money, but he’s expected to raise a family on that. I think that’s kind of how everybody is now — or a lot of people are. Minimum wage is not a living wage at all. But you want to do the things you want to do with your life. People want to get married, people want to have kids and stuff, but what are you going to do?

It’s not even about education. I know a lot of people who graduated from college and they were still working the same restaurant jobs that I was working, only they had a lot of debt. It’s a very modern story, a modern struggle. You’re just fucked, and there’s nothing you can do about it. I guess that’s why he would turn to alcohol and drugs and stuff, too. When you’re just busting your ass to keep your head above water, you need some kind of escape.

That’s part of what was so real about it for me. I knew people like this growing up and it’s very real. No one, or almost no one, chooses to become an alcoholic; you just get so burnt out busting your ass to stay above water and you need an escape and what you can afford is cable TV and cheap beer and eventually that takes over your life.

That’s the kind of story it is. When people read it, hopefully they do recognize things from their own life and own experiences, and people that they know in their life and they relate to it. That’s a good thing.

It’s hauntingly realistic, and kind of beautiful for that.

People keep writing that on Twitter. They’re so disturbed by it. I spent a lot of my early twenties in Lakewood and that was just everybody that I knew around me. I worked at Einstein Brothers and I remember I got a raise to $8 an hour and I was like, “Holy shit! $8! It’s fifty cents more than I was making. This is incredible, what am I going to do with all this extra money!” And then the checks start to come in and I’m like, “Oh wait, this is nothing, still. The struggle wasn’t over. If I get sick or something, if I miss a day of work, what am I going to do? How am I going to pay my rent?" It’s so heavy. That’s most people’s reality. You have to know somebody or grow up rich to be successful anymore. It’s really depressing.

It’s soul-deadening. I think, growing up, we all believe that at a certain point you get the right job or right opportunity and things turn around, but for most of us that never comes. It’s just more of the same, until you die.

And everything keeps getting more and more expensive, especially in this town. I don’t know anybody who has any real money, but apartments keep raising their rent more and more. I’m like, “Who can afford this?” I don’t understand that. These luxury lofts, they’re not for people who live here. They’re for people who are moving here from California or something. I don’t know who can live like that. This is kind of grim, but I went to Riverside Cemetery because I thought it was interesting, seeing all the graves and everything. I came home and I was wondering, how much is a grave? What’s going to happen to me? Am I just going to end up in a canister somewhere? I looked up burial plots and I’m just like, “Who the fuck can afford a burial plot?” That’s so expensive, man!

I think a funeral costs like $10-12k, if you actually want to get buried somewhere.

Oh, man, I’d have to have a Kickstarter for my own funeral. It’s so bleak. Everything is so expensive. It’s really horrible. I was thinking about Detroit, how it’s like full of all these houses who were built and lived in by people who worked in a factory all day. And now, it’s like, you work in a factory, you can’t afford a house. These people all had houses and stuff. Now it’s like, no way! You have to get like ten of your buddies together and rent out a house. It’s frustrating.

How long did it take to write and draw Saint Cole? Do I remember correctly that you were starting on it around the release of The Hypo in October 2012?

Yeah, I was. I wrote it while I was working on The Hypo. I started drawing it basically as soon as I finished The Hypo. It took a couple years, working around other projects. I was serializing on a website called The Expositor.

The other release for this event is the latest Blammo, right? That’s more of your short story work?

Yeah, it’s all short stories. This is [issue] 8 ½, so it’s mostly stories that have been published elsewhere that I’m collecting together. That’s why I called it 8 ½. If it were issue No. 9, it would be new stuff. This is stuff that was scattered around and also some artwork.

And it’s full color, which is not something you usually do?

Yeah, full color. And this is the first time. Kilgore published it and this is the first time they’ve done something in full color. It’ll be interesting. It’s stuff that I’m proud of and that I want to bring together in one place so people don’t have to search all over for. There’s a lot of sad stuff in there, too. Some diary comics are in there.

You seem drawn to the sadness of life. Your stuff is funny, too, but the sadness seems to always be there. Is that fair to say?

Yeah, well, anyone who's really funny is also really sad. It’s two different ways to deal with sadness. You can be sad, or you can laugh about it. I guess you can be angry, too.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Billboard - Slot Inline - Content - Labeled - No Desktop",

"component": "23668565",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "STN Player - Float - Mobile Only ",

"component": "23853568",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - 2x Rectangles Desktop, Tower on Mobile - Labeled",

"component": "24956856",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard to Tower - Slot Auto-select - Labeled",

"component": "17676724",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]