As the clock ticks past six and the presenter still hasn’t arrived, a city employee turns on a video promoting the housing plan. Slow-moving string music fills the room as Mayor Michael Hancock’s face fills the projection screen. “Housing an Inclusive Denver, our new five-year housing plan, celebrates the diversity of neighborhoods, and identifies ways we can deploy our resources to keep Denver a vibrant, affordable city,” Hancock tells the camera.

The video then shows sweeping shots of parks, neighborhoods and newly constructed affordable-housing complexes, all backed by chirpy narration and soft guitar music, creating a vibe not unlike that of a Cialis commercial.

What’s missing are shots of homeless encampments along the South Platte River, scenes of people being priced out of their homes after having lived in them for decades, footage of young adults scouring housing ads on Craigslist, then showing up to interview with landlords alongside many others vying for the same room.

“I’m sorry for being late!” booms Erik Soliván, who finally arrives just as the video is ending. Looking slightly flustered, he mutters something about a packed schedule that day.

The director of the mayor’s new Office of Housing and Opportunity for People Everywhere (HOPE), Soliván is the driving force behind Denver’s five-year affordable-housing plan. This is the third public meeting on the plan, which still must be approved by Denver City Council and the city’s Housing Advisory Committee — a 23-person group chaired by Kevin Marchman of the Stapleton Development Corporation that includes city officials and members of such organizations as the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless — before it can go into effect.

Soliván and the Mayor’s Office recognize that this city has an affordable-housing crisis. The five-year plan is their vision document to help over 30,000 households by 2023 and prevent Denver from becoming the next San Francisco or Brooklyn. Before outlining some of the plan’s action steps, Soliván shares a PowerPoint presentation that highlights sobering facts about Denver’s affordability crisis:

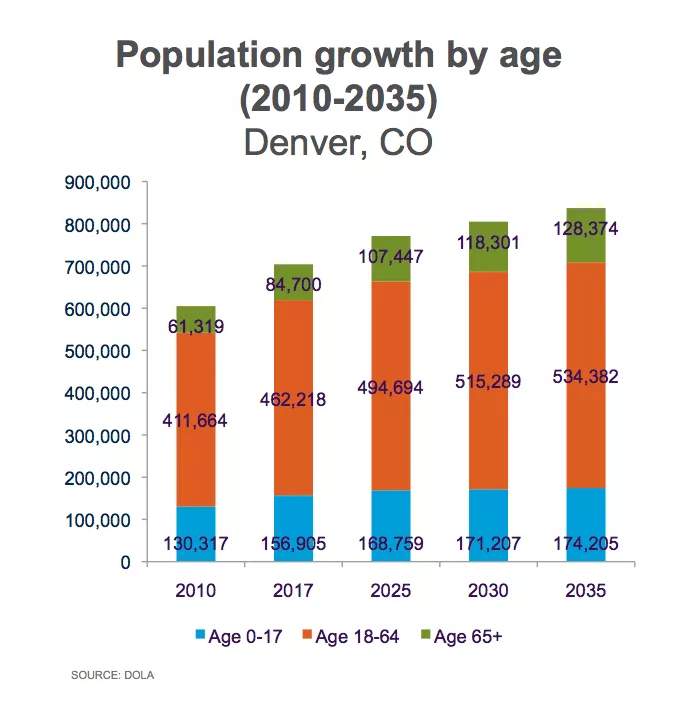

• More than 100,000 people have moved to Denver since 2010. That number continues to rise by between 750 and 1,000 people each month.

• Between 2011 and 2016, the average rent in Denver increased by 46 percent, from $941 to $1,376, and it increased 16 percent between 2014 and 2016 alone.

• There are nearly 68,000 renter households and 35,000 owner households that are paying too much for housing (defined as more than 30 percent of their income).

• There is a shortage of approximately 26,000 housing units for the lowest earners (who make $17,650 or less per year).

• At least 3,336 people are experiencing homelessness on any given night in Denver.

• The number of seniors in Denver will increase by 52 percent between 2017 and 2035, representing the largest share of the city’s population growth over that time. Many aren’t adequately preparing for retirement.

But at this November 8 meeting, it’s clear that slick videos, PowerPoints and a dense, 98-page plan won’t fully appease community members worried about their future in Denver. “I want to know how this plan will solve homelessness!” yells a man, who goes on to describe the unsanitary conditions he’s been experiencing in some of the city’s shelters.

“I work full-time as a teacher, and I don’t know how much longer I can afford my rent or where I’ll go,” says another woman, practically in tears."I don’t know how much longer I can afford my rent or where I’ll go."

tweet this

Soliván proceeds to describe some of the funding mechanisms that the city will use to address homelessness and the rental market, but he knows his technical descriptions of things like impact fees and public-private partnerships go over many people’s heads. So more than anything, the meeting has the feel of group therapy. “I know you’re hurting,” he says, multiple times.

A lot is riding on Soliván. While he hates the label that many media outlets have given him — “housing czar” — that’s exactly what he is. The city is pinning its hopes on Soliván knowing what to do with HOPE, from making zoning recommendations to using federal subsidies.

Since he arrived in Denver in January, Soliván has taken a markedly different approach to homelessness and housing than the city used before; the five-year-housing plan is the culmination of his first nine months on the job. How it changes before it’s finally approved — and whether the whole plan gets torpedoed by tax overhauls in Washington, D.C. — could affect the demographic and economic landscape of Denver for decades to come.

Soliván realizes what’s on the line. He knows all about the importance of housing from his own experience.

Erik Soliván vividly remembers the day when he truly learned that there are two Americas.

In 1993, Soliván — then a freshman in high school — was invited to visit the house of a wealthy student, Chas Peruto, whom he’d met at the private preparatory school where Soliván had a scholarship. Many of his classmates didn’t know that where Soliván lived in Hunting Park, an industrial area of north Philadelphia, his family regularly drew provisions from a food bank and sometimes had to sit by the stove in their house to keep warm during the winter because the radiator was broken.

Peruto, by contrast, was the son of a well-known criminal defense lawyer and lived in Gladwyne, one of the nicest suburbs of Philly. When Soliván arrived at Peruto’s house, it seemed massive. As he passed through the doorway, he gazed up at the high, arched ceilings that formed the atrium. “Incredible,” he remembers thinking.

Still, Peruto’s house was just a tease. After Soliván arrived, Peruto suggested that they’d have more fun visiting another classmate, Wendi Barish, at her home, a mansion that dwarfed Peruto’s.

“Wanna drive go-karts?” Barish asked the two when they arrived.

“What do you mean, ‘go-karts?’” Soliván replied.

When they got to the back yard, Soliván’s question was answered: The yard was so large that it included a full go-kart course that wound through the manicured landscaping.

“It was amazing; it still sticks with me to this day,” says Soliván. “To go to these homes and realize there were two Americas was a driving motivation once I got an opportunity to start this work, saying, ‘How can we create more equity?’”

The “other” America that Soliván knew was defined by struggle. The grandparents on both sides of his family were from Puerto Rico; after they’d settled in New York City, they’d lived in the same public-housing development. Soliván’s parents met at church; they had a baby girl — Soliván’s sister — when his mom was eighteen years old.

Living in the projects was tough, crowded, stifling. In 1979, just a few years after the federal government began the Section 8 voucher program to provide subsidized housing, Soliván’s parents had an opportunity to enter the program and get out of New York City. They accepted relocation to Hunting Park, a North Philly neighborhood characterized by racial segregation, blight, row homes, dilapidated houses and large factories. Soon after they moved, Erik was born.

The young family made the most of their new home. Soliván’s mom worked as a secretary for the Federal Reserve, and his dad got a job at a box-cutting factory, inserting huge rolls of paper into machines that shaped them for packing. After a ten-year grind — and moving the family through multiple rental apartments — Soliván’s father was promoted to a supervisor at the factory. With his increased income, his parents were able to buy their first house in Hunting Park in 1989. It cost $61,000.“It may have been tiny — just two bedrooms and a bathroom — but for them it was a crowning achievement,”

tweet this

“It may have been tiny — just two bedrooms and a bathroom — but for them it was a crowning achievement,” says Soliván.

Having a stable living situation changed a lot for the family. Both parents were able to take one or two community-college classes per semester for years, so that six months after Soliván obtained his undergraduate degree from Haverford College in 2001, his mother received her graduate degree in education. His father earned his own a couple of years later. Now they both work as teachers.

“Within a three-year span, we all got our degrees,” says Soliván. “Their path and moving up the scale from public housing to entry-level home ownership, that’s a path and opportunity that drives the work I do.”

It first drove him to help Democrat Ed Rendell’s successful campaign to become governor of Pennsylvania in 2003. That led to a position as assistant to the state’s deputy secretary for community affairs and development, where Soliván worked to find ways to use federal housing programs in formerly prosperous factory cities like Scranton, which were transitioning into blight as factories closed.

Later he obtained a law degree from Rutgers University, then joined a private firm that helped distressed municipalities turn around their finances. From there, Soliván returned to government work, moving up to become senior vice president for the Philadelphia Housing Authority, the fourth-largest housing authority in the United States. In that post, Soliván developed a theory: Housing issues, including homelessness and supportive housing, can’t be viewed within their own bubbles. Rather, they are all interconnected, so a program that tackles one housing need affects other areas.

“We have all these different offices, but what happens in government a lot is that they end up in silos, and we’re not connecting the dots on this work,” Soliván explains. Instead, he says, different services and departments need to work in concert to solve housing challenges.

In Denver, Hancock’s administration was beginning to see housing in a similar light. In July 2016, the mayor announced in his State of the City address that he was forming a new office called HOPE to coordinate housing and homelessness services. He began a nationwide search for its director (at an annual salary of $135,000 a year) and announced Soliván’s appointment at a press conference on January 9, 2017.

“I heard about the job here in Denver through LinkedIn,” says Soliván. “I saw the role as providing an opportunity to lead the collaborative development of housing policy, and I have the chance to work with a mayor who has a similar background to mine and whose values and life experiences inform his policy decisions, because policy impacts people, and the people should impact policy.”

Soliván dove head-first into the job, working long hours as he charted the constellation of community groups, advocacy organizations, developers and service providers in Denver to understand how everything fits into the complicated puzzle called “housing.” He finally took his first drive up I-70 into the mountains in early November, for a housing conference in Vail.

Despite his sometimes serious demeanor, Soliván has a few quirks, including a large collection of outrageously colorful socks that he likes to wear with his leather shoes. He also loves whiteboards. And anytime there’s a whiteboard around, you can be sure that he’s going to draw “the spectrum.”

The spectrum is at the center of the five-year-housing plan, and it’s what drives Soliván’s housing philosophy. Between the spectrum’s two poles — homelessness and home ownership — is a continuum of housing stability: Starting from homelessness, the spectrum stretches through transitional-housing programs, supportive housing like Section 8, the low end of the rental market, high-end rentals and starter homes for first-time homebuyers, and then ends at market-rate housing stock. The operating principle is that everyone is trying to work their way toward more stability — which for many would conclude in home ownership. But there are stressors and obstacles all along the spectrum because of market demands, affordability issues and lack of government support.

When Soliván was hired by Hancock, Denver had already made moves to address affordable housing. There was Hancock’s 3x5 initiative, which ended up producing 3,000 affordable units between 2013 and 2017. And in fall 2016, Denver City Council approved the city’s first dedicated fund for affordable housing, a $15-million-a-year fund that seeks to create or preserve 6,000 units of affordable housing over a decade.

“I saw the role as providing an opportunity to lead the collaborative development of housing policy."

tweet this

But Soliván has already shifted the city’s focus by persuading the Hancock administration that merely using the fund to build affordable units is a wasteful use of money. Much of his argument comes down to math. At $250,000 per affordable unit, he points out, Denver won’t be able to put much of a dent in the affordable-housing crisis during that ten-year period — especially not with 1,000 people continuing to move to the city each month.

“You can’t build your way out of this,” Soliván says. “Let’s say that there are 20,000 affordable units needed today, times 250k per house; that brings you to $5 billion. That’s three times the city budget. We’re just chipping at it here. But if we can chip at some of the existing resources and maximize some leverage and get additional resources, we can make a bigger impact overall.”

While the $15-million-a-year fund remains the backbone of Denver’s approach to affordable housing, the program will no longer focus just on building new units (whose number has now dropped to 3,000). Instead, the five-year housing plan relies on Soliván’s “spectrum” to identify targeted interventions and programs that can help residents move their way toward stability and eventual home ownership — even if they’re starting from a position of homelessness. Those interventions include city-run initiatives and programs already offered by nonprofits.

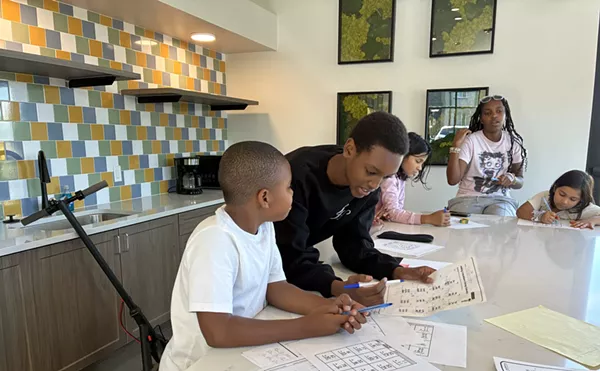

The many moving parts are among the reasons that the proposed “Housing an Inclusive Denver” plan is so complex — and difficult to communicate during a two-hour meeting like the one at Calvary Baptist Church. Soliván finds it easier to explain the kind of people who will be helped by the plan, illustrating with individuals who’ve already moved along the spectrum toward better housing or even stability.

“Hearing examples like these will help you understand how some of this will work,” he promises.

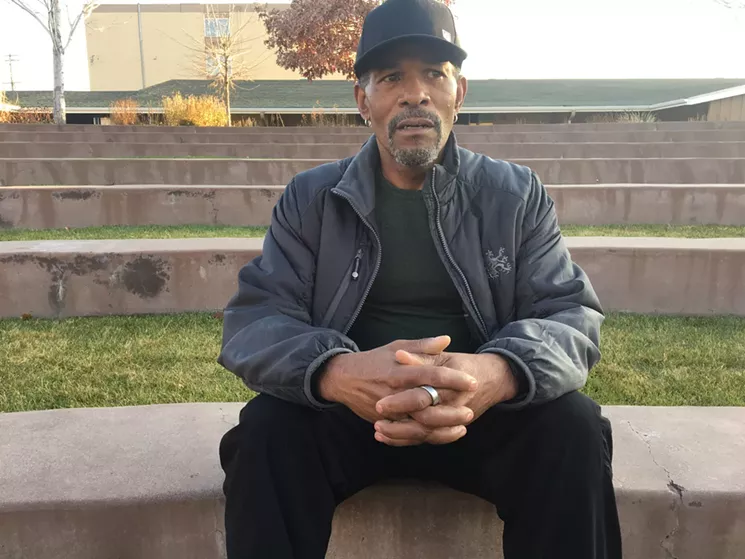

After experiencing homelessness, Reggie Pulley was recently placed into transitional housing.

Contrary to the stereotype that homeless people are loafers who refuse to work or contribute to society, the latest street survey in Denver, conducted by the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative, found that a majority of the homeless population works; many people just can’t afford a place to rent. According to the survey, 61 percent of the respondents experiencing homelessness reported that either they or a member of their family had worked and made some income in the past month.

Pulley, a veteran, moved to Denver after a helicopter company he was working for in New York went under. He was living with siblings in Denver before a lifelong addiction got the better of him. “Because of my alcoholism, I ended up being homeless,” says Pulley. That’s when he checked into the Denver Rescue Mission.

The service provider first helped him get sober through its New Life anti-addiction program. Then, while Pulley was living at the shelter, the Denver Rescue Mission connected him with Emily Griffith Technical College, where Pulley took culinary courses and received a cooking certificate that he used to land a job at a hotel downtown.

After living at the shelter for months, he’s now joined around 175 other people at the Denver Rescue Mission’s transitional-housing complex in northeast Denver, the Crossing. Pulley pays $500 a month to live there, and says the Crossing’s STAR program is allowing him to save money for his eventual transition to the rental market when his two-year housing period ends in 2019. “There are people I know who have apartments, and they’re like $900 to $1,200 dollars per month, which I could probably afford [with my job], but I’d be broke just paying rent,” Pulley explains. “It would be a big strain on me. I do want to take the next step and get an apartment and eventually get a house, but there are things along the way I need to do — like make sure my credit is squared away, that I have savings — and this is a great stepping stone for me to get to that end goal.”

With the aid of that small program run by a nonprofit, Pulley is moving along Soliván’s spectrum, from homelessness to transitional housing to the rental market. But there are new challenges as an individual enters the rental market, and to help meet them, the city launched a new eviction-mediation program on October 10.

Shane Hewitt, a 57-year-old disabled veteran, found himself facing eviction and court proceedings in October after he fell three months behind in rent at his apartment complex in the Golden Triangle neighborhood. It was an unanticipated situation, Hewitt says, precipitated by his wife moving to California to deal with family problems there. Hewitt was using some of his disability and pension payments to support his wife and fell behind on rent.

Hewitt found the eviction-mediation program online. After reaching out to the program — which is staffed by a former municipal judge and six mediators — he received a call from his landlord, who said that the city had contacted him and that he was willing to work out a deal with Hewitt. After analyzing Hewitt’s income, the two agreed to a payment plan: Hewitt will pay a little extra each month to make up for the three missed rental payments. Hewitt says his wife is supportive and will take less money so that he can make ends meet in Denver.

“I think that if I hadn’t called the mediator with the city, I probably would have been evicted."

tweet this

“I think that if I hadn’t called the mediator with the city, I probably would have been evicted,” says Hewitt. “I think [my landlord] thought, ‘Oh, wait a minute, the city’s getting involved in this, so maybe I’d better do something.’”

In 2016, more than 6,000 renters were evicted from their homes in Denver. The city is banking on its new eviction-mediation program, along with another program that pulls $865,000 from the affordable-housing fund to provide temporary utility and rental assistance, to lower that number. And the challenges continue at the far end of the spectrum, where Soliván sees a combination of smaller initiatives and partnerships helping those who are trying to get out of the rental market and into ownership.

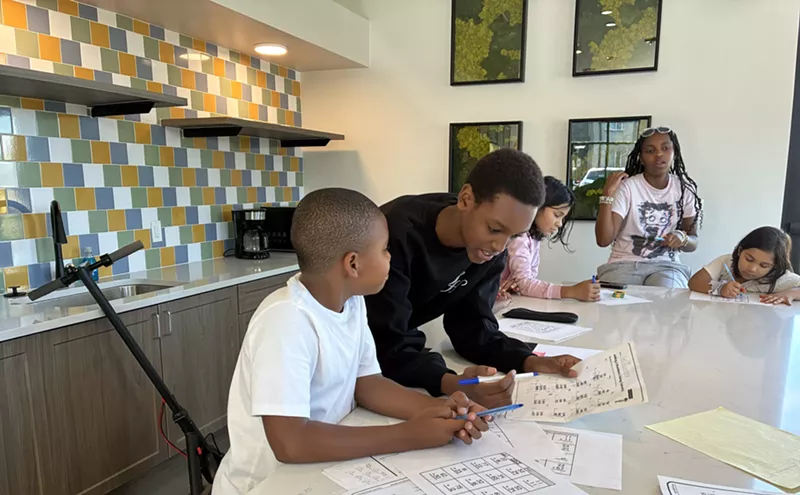

Hewan Berthe is a single mother who moved to Denver in 2013 from the East African nation of Eritrea. Like Pulley, Berthe was working — at Walmart, for $8 an hour — but wasn’t able to afford rent, especially while raising three kids. Berthe was able to secure a spot at Warren Village, a transitional-housing complex for single mothers run by a nonprofit in Capitol Hill. With a two-year housing lifeline, she found another job in telecommunications and earned enough income to qualify for home ownership through Habitat for Humanity.

Habitat for Humanity has its own rigid set of requirements to enter the home-ownership program, but Berthe says that volunteering hundreds of hours of “sweat equity” to help build a three-bedroom, two-bath home in southwest Denver and meeting with caseworkers who conduct probing financial checkups was all well worth it. Now Berthe pays a fixed rate — 30 percent of her income when she applied in 2015 — for a thirty-year mortgage on the home. Habitat for Humanity provided the down payment.

Still, competition to get a home through Habitat is fierce. “For one house, more than 1,000 people apply, so I felt very lucky,” says Berthe.

Given how many people need help, can these initiatives really make much of a dent in the affordable-housing crisis? Soliván thinks so, but not without the city tackling problems all along the housing spectrum, so that people can avoid “bottlenecks” as they work their way toward better housing.

“The impact of the programs are limited, because if you think about the spectrum, if you can’t move people up that continuum, you’re just putting more people in a waiting space,” says Soliván. “But we can get rid of the bottlenecks by being more intentional about the creation of low-income housing.”

“My mother was never unemployed...but we moved every six months, which meant we had to move schools every six months as well, and it wasn’t until we got into stable public housing that my life, my academics, relationships, began to really take off,” he continues. “So I recognize the importance of stable housing. I recognize particularly the development, health and well-being of children. That drives a lot of what our focus is here in the city of Denver.”

To see the big picture of what the city’s envisioning, you need to consider all parts of the new housing plan, Hancock says, as well as how it works with such ongoing efforts as Blueprint Denver — which is redrawing zoning throughout the city — and Denveright, a community-driven effort launched in the summer of 2016 to provide guidance on transportation, mobility, parks and zoning.

“It’s economics: We’ve got more demand than we’ve got supply,” Hancock explains. “There’s a perfect storm happening, and we began to see that in 2010, 2011. When I came in as mayor...we were still in the throes of the recession, so it was not as prominent an issue as it is today...but all of a sudden, Denver’s economy took off, with more people coming in, at a clip of 750 to 1,000 per month, and more people looking for apartments. In 2012, we really began to sense that we have a challenge in Denver. And 2013 is when we started rolling out a lot of our responses to the affordable-housing challenge.”

The struggle to find housing hits close to home for the mayor. “And not just friends and colleagues,” he says. “I’ve got family members. My son said it to me! He’s 22 and just starting his career.”

To increase the housing stock in Denver, the city is looking at changing zoning in some neighborhoods so that property owners can build accessory dwelling units — rooms on top of garages, for example. Denver is also searching for additional funding through federal programs like Medicare and Medicaid, which could help support housing initiatives as long as the programs fulfill the federal government’s esoteric requirements by including things like caseworkers, addiction counselors and workforce training. Denver’s Department of Human Services just hired a full-time underwriter to explore such opportunities, Soliván says.

“You can’t build your way out of this.... We’re just chipping at it here."

tweet this

But perhaps the most innovative aspect of the city’s five-year housing plan is the Lower Income Voucher Equity program: LIVE.

This is the program that responds to Soliván’s mantra that “You can’t build your way out of this.” The concept is for Denver to use some of its affordable-housing fund — nearly a million dollars, with an additional $500,000 thrown in by private partners — to bring down the rents of vacant luxury units in Denver.

A majority of the newly constructed rental units during the past several years have been luxury units “with prices that are far beyond reach for even Denver’s middle-income earners,” the housing plan notes. Because developers have focused on luxury units, there is too much supply at the high end of the rental market — creating a vacancy rate of 10 percent for luxury homes, or nearly 2,000 empty units.

This month, Denver will start working with property owners to fill those units — chipping in city dollars to lower rents to an affordable rate. Soliván hopes to have the first families housed through LIVE by the end of 2017; he eventually wants to fill 400 vacant luxury units through the program. By having middle- to low-income families move into the subsidized luxury units, the city can ease some of the pressure at the low end of the rental market, where there is far too much demand for supply.

“I’ve had calls from over twenty cities that are interested in this,” says Soliván, listing off Baltimore, Austin, Seattle and San Francisco. “My former colleagues in Philly even called me.”

But not everyone is as enthusiastic as Soliván about various aspects of the housing plan.

“Fifteen million a year is just not going to get it done,” he continues. “City neighborhoods are changing in a matter of months, not years, right now. We realized we needed a more aggressive way to fund this stuff, and we were motivated by about two dozen different cities and counties throughout the West that have in the last few years issued bonds to support affordable housing.” So All In Denver hired a professional polling service, which found that two-thirds of the poll’s respondents were willing to pay increased property taxes to support a $200 million affordable-housing bond.

But when All In Denver approached the city with a proposal, “the administration was resistant to this idea,” says Segal. “The city administration to date has been closed-minded to this approach. They’ve been suggesting that there are other priorities that would require this type of funding before housing. That’s fair. But the follow-up question is, ‘Okay, what is that? What’s more important than the housing crisis in Denver right now?’…. What is not matching right now is the mayor’s rhetoric on this issue and his desire to address it in an aggressive way.”

If Hancock had wanted to be aggressive, Segal suggests, he could have included funding for affordable housing in the GO bond measures passed last month, which will cover nearly a billion dollars’ worth of projects around the city.

Instead, All In Denver hopes to put a $200 million bond for affordable housing on the ballot in 2018, and at least get a mention of it in the five-year housing plan. “If our housing bond is not included in the housing plan in a substantial way through the work of the Housing Advisory Committee, we fully intend to press ahead with Denver City Council and work with it to get the bond placed into the housing plan,” says Segal. “Honestly, we feel we have the support there; we have champions there.”

And Segal points to another alarming gap in the plan: The $15-million-a-year fund that Soliván is using to finance the housing plan is already short by over $6 million in its first year. That’s because the fund is supposed to raise some of its money through “linkage fees” paid by developers when they file permits to construct apartment complexes — but before the new fees went into effect in 2017, developers rushed to get their permits through in 2016.

“So that’s another question,” says Segal. “It’s like, ‘Dude, your $15-million-a-year fund only brought in $9 million the first year.’ That’s another reason to bond, because you know with certainty that you’ll have the money. And right now the linkage fee is totally speculative.”“It’s like, ‘Dude, your $15-million-a-year fund only brought in $9 million the first year.’"

tweet this

Soliván acknowledges that the fund is about $6 million below its projected balance for 2017 because a rash of developers filed early to avoid paying the fee. “There was a rush to get in permits before the impact fee went into effect,” he says. “But it will ebb and flow, so next year you’ll probably see a pop.” To make up for the gap, the city filled the $6 million shortfall with money from the General Fund.

In the meantime, a bond “is on the table,” Soliván says. “We all agree we need more, but our focus has always been, and continues to be, ‘How do we do this responsibly?’ Because we want to maintain our credit rating, and now we just put $937 million out on debt [by passing the GO bonds], and every time we add to that debt by bonding or certificates of purchase, that has an impact on credit rating. We have a triple credit rating with all three bureaus, and we want to maintain that.”

And there’s another reason affordable housing wasn’t included in the GO bonds. “Because we haven’t even completed the [housing] plan yet to address the $15 million fund,” Soliván explains. “Part of our thinking on housing policy is, ‘Let’s look at the entire landscape of need and how to maximize existing resources and look at additional resources and where to place them.’ And in terms of priorities, there’s a lot in the GO bonds that will lay the groundwork for affordable housing.”

For example, he continues, some of the road and transportation improvements made possible by the GO bonds in areas like Sun Valley will allow for investment in, and access to, future affordable housing there.

“We’re really suffering here in part because of the city’s investments, so we’ve gone to them and said, ‘Come be our partner instead of a competitor,’” reports Robin Reichhardt of the GES Coalition, who says that request has gone nowhere.

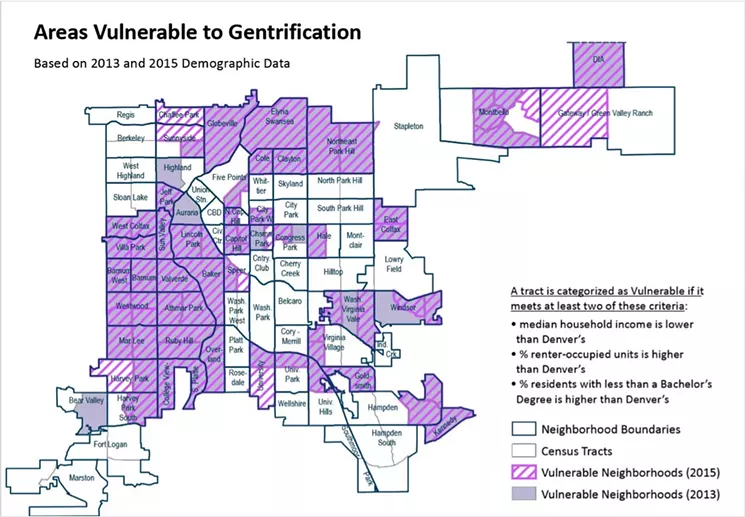

Globeville and Elyria-Swansea definitely qualify as gentrifying under the city’s own definition of gentrification: “when more affluent people move into older, often disinvested areas, causing property values to increase and resulting in the displacement of lower-income residents.” The GES Coalition conducted independent research that found that nine out of ten households in the neighborhoods are “cost burdened,” meaning that residents pay more than 30 percent of their income on housing. With those findings in hand, the group started exploring the possibility of setting up a community land trust.

By buying up parcels and owning the land underneath tenants’ homes, a land trust can prevent the type of rapid market appreciation that prices out longtime residents. In July, after reaching out to national consultants, the GES Coalition submitted a land-trust proposal to the city, asking for a commitment of $2 million to $3 million and explaining how the land trust would have a tripartite board of residents, neighbors and stakeholders/experts. “A land trust without the ‘C’ — community — is just a way to bank land,” explains Reichhardt. “We’ve seen citywide land trusts fail because they’re not responsive to the individual needs of each neighborhood. Very easily, a citywide land trust could be brought here [to GES] and used to displace more people.”

The GES Coalition didn’t get far with city officials, he says. And then, at a community meeting last month, “they pulled the mask off and said, ‘We’re going to do a $25 million citywide land trust, and you guys aren’t part it.’

"Finding where the government is responsible for intervening in the housing market is surgery. It's not a butcher shop."

tweet this

“So they’ve been completely clandestine about doing this, all while using our name — saying, ‘Oh, the GES Coalition wants a land trust,’” continues Reichhardt. “I think the mayor and his partners like Erik [Soliván] are so arrogant in thinking they can individually solve a complex, multi-decade problem. It’s just ridiculous. They are even unwilling to show they’ve done their homework. These types of plans look really great — having $25 million promised for a fund — but how is that going to be accountable to neighborhoods? How is that going to do anything except build more mid-level housing?…. Erik completely dismissed our plan. He wouldn’t hear about how it would work.”

Soliván confirms that the HOPE office is working on a proposal for a centralized land trust — no dollar amount has yet been established — that would have representation from all the affected neighborhoods. “In a dense, populated city, you can bring expertise together while neighborhoods still have a role, and I’m still trying to continue the conversation,” he says.

He says he’s been talking with members of the GES Coalition like Candi CdeBaca for months, and doesn’t believe that group is ready for its own land trust. “I would contest their claims and say that they don’t have it figured out yet,” he adds. “That’s tough for people to hear; that’s a tough conversation. They’ve done tremendous work in moving this conversation forward…but as a steward of public funds…I can’t say that they can approach me and say, ‘We have it all figured out, just write us a check,’ when I know this is not figured out yet.

“This is complicated work,” he adds. “And finding where the government is responsible for intervening in the housing market is surgery. It’s not a butcher shop.”

On December 7, the Housing Advisory Committee will discuss possible revisions to the housing plan, including how a citywide land trust could work and whether an additional housing bond should be included.

But conversations far more critical to the plan are already taking place 2,000 miles away. All of Soliván’s work — eleven months of talking with people across the city, studying existing services and then creating the proposal — could be stymied by the Republican tax overhaul now being hashed out in Washington, D.C. Congressional Republicans, desperate for a legislative victory during Trump’s first year in office, are on track to pass new legislation before the end of December. A final version of the bill, which would merge the House and Senate versions, is being negotiated in a congressional conference committee.

The House proposal would eliminate tax-exempt bonds — the foundation of low-income-housing tax credits, which are used to build the majority of affordable housing in the city. And according to Soliván, it would also end other budgetary mechanisms, like the ability to refund existing GO debt. “All of that would have an enormous impact, to the tune of thousands of affordable units,” he says.

While the bill that passed the Senate on December 2 isn’t as harsh, “it still creates a ton of problems,” he adds. “We would have to back up and rethink a lot of the strategies and priorities. And at that point, our affordable-housing dollars are just replacing all of those lost federal dollars.”

Affordable-housing funding would drop not just in Denver, but across Colorado. “We would see private production of 3,400 [affordable] units per year in Colorado drop to about 700 units per year,” says Hancock. “It would be devastating. We simply cannot allow that to happen. So we immediately sounded the alarms for our delegation — working with our senators as well as our local representative, Diana DeGette — and we have very well-paid lobbyists working in Washington.”

While he waits for the final word from Washington, a frustrated Soliván says that he’s going to continue operating on the assumption that his housing plan has accurately identified the programs and dollars to help more than 30,000 Denver households by 2023.

The longer Denver waits to deal with its affordable-housing crisis, the higher the stakes.

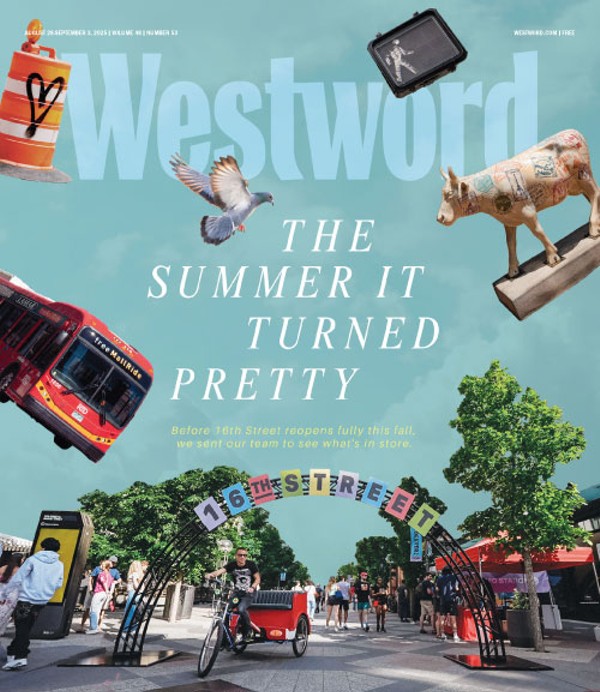

On November 22, a branch of Ink! Coffee on Larimer Street ignited a powder keg of resentment with a sidewalk sign that declared, “Happily gentrifying the neighborhood since 2014.”

The advertisement — which the coffee chain’s owner says was meant to be a joke — has sparked a citywide conversation (not to mention national media coverage) regarding neighborhood identity and affordability. The protests and social-media backlash put the mayor on the defensive, as some critics questioned what the city has done to curb gentrification since Hancock took office in 2011.

Soliván himself has been called on to defend city policies that predate his tenure at HOPE. He had to testify against a homeless “right to rest” bill at the State Capitol in April, and was also pushed in front of a camera to justify the city’s homeless sweeps policy when VICE made a documentary in Denver over the summer. Just the other day, Soliván was heading to the gym when a man who recognized him from TV confronted him. “I’m living in a motel right now. How can you help me?” the man pleaded.

“I’ve spent much of my career in positions that are subject to criticism,” Soliván says. “I don’t personalize any of it because — and this was the mayor’s term for me — you blame the ‘head coach’ first. Just like the Broncos right now: When things aren’t going so well, you blame the head coach. I know this issue is filled with a lot of emotion because people are hurting. I know this issue is filled with a lot of angst and anxiety because people want to see a city that they can be a part of.”