Marvin nods as he listens to his friend's comments, and a half-smile implies that he's glad to have this cop watching out for him. It wasn't always so: As soon as Marvin took over the afternoon-drive shift at KHOW in September 1996, he started making enemies, including police who found his daily "pig reports"--in which he revealed the locations of traffic squads against a backdrop of pre-recorded oinking--less than hilarious. But following the November 1997 murder of Officer Bruce VanderJagt by a man reputed to be a skinhead and an incident in which a dead pig with VanderJagt's name carved into it was left outside a police station, Marvin dispensed with the oinking shtick and became one of the biggest boosters of the city's boys and girls in blue. Now many badge-wearers from throughout the metro area adore him, as do a growing legion of talk junkies, and the voters for the Colorado Broadcasters Association, who last Saturday named Marvin Denver's best news/talk personality. There remains, though, a portion of the public for whom Marvin is not just an annoyance, but a threat. And if one of them decides to register disgust with a revolver or a shiv, Marvin knows that having a cop on hand would be very good.

"I might seem like a rough, tough person--like, 'Fuck them. Let them come and get me,'" Marvin says. "But I do get scared sometimes. I do. But what choice do you have, man? Do you buckle under to it? Or do you say what you've got to say?"

For the most part, Marvin, who's 45, takes the latter course. But that doesn't mean he's a single-minded confrontationalist dedicated to provoking the ire of anyone within hearing range. He's more complicated than that. He says he's been diagnosed as a "bipolar manic-depressive," and from 3 to 7 p.m. every weekday, he does his best to prove it. In his decade as a talk-show host, his routine, which has already served him well in other cities, has been powered by mood swings--and swing his moods do. In contrast to most other on-air yakkers, who present predictable viewpoints in predictable ways, Marvin hops from one extreme to another like a barefoot child on a hot sidewalk. The happy, stable, lovable Marvin venerates music, movies, animals, food, humor and dishing with co-workers and callers. But just when you think you've got him pegged as a pushover, up pops a Marvin who's belligerent, militant, capricious--a wild man with a mammoth chip on his shoulder. One minute he's mellow, the next he's as furious as a man in a straitjacket with an itch that won't go away.

In other words, Marvin is two, two, two hosts in one--and he says even he doesn't know which of them will come out, or when. "There are some days when I go in and I can't summon the energy to try to convince people of my point of view," he says. "And then there are days when I'm in a good mood and I think to myself, 'My God--what does it take to get through to these people?'

"I think it's a hundred percent permissible to start yelling at each other, and I think it's a hundred percent permissible to get down and go for it. But that doesn't mean I hate the callers. And it doesn't mean we can't be friends."

It's not difficult to understand why some folks would be gun-shy about taking Jay Marvin up on this offer. When he sees a wrong that he feels needs to be righted, his two minds become one, and he strikes with a vigor that would earn the average pooch a rabies shot. Just ask Glendale mayor Joe Rice.

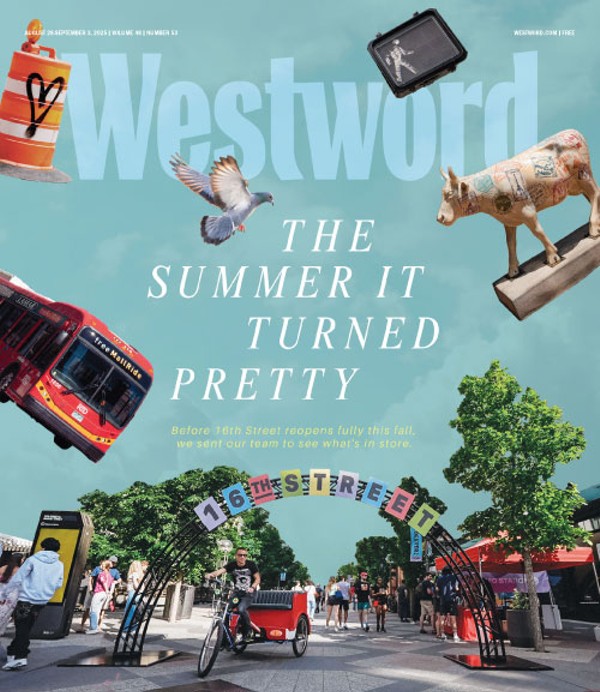

The conflict between the pair first arose on February 27, when Marvin denigrated a Rice-backed proposal aimed at placing restrictions on the tiny city's strip bars; if passed, one of its provisions would have effectively eliminated table dancing by requiring that peelers remain at least six feet from patrons at all times. Marvin charged that the Glendale proposition duplicated an ordinance drawn up by the National Family Legal Foundation (NFLF), a right-wing religious organization. (The city's link with the NFLF was first reported February 12 in Westword.)

As Rice tells it, he was at his day job (he works for MCI) when he learned about these assertions and was informed that Marvin had dared him to debate the topic live. Rice took the bait and phoned KHOW, much to his subsequent chagrin. "What I learned was, it's not about the truth," Rice says. "It's about entertainment, and it's about fueling the fire for a debate to make it a lively show. His technique is to ask you a lot of complex, rapid-fire questions that are really several questions in one. And if you start to answer them, he's like, 'Stop beating around the bush. You're acting just like a politician.' He insists on yes or no answers to questions that can't be answered that way."

On Marvin's show, Rice did not deny that the Glendale ordinance had been influenced by the NFLF document Marvin had cited, but he insisted that language from laws in Commerce City, Aurora, Lakewood, Denver and other cities across the country had also been folded into the Glendale plan. Marvin wasn't buying it: He called Rice a pawn of the Christian right and defied him to prove that the Glendale ordinance differed in any way from the one promoted by the NFLF.

Later that afternoon, Rice responded by dropping into KHOW's studio. But beyond a colorful exclamation from Marvin--"Get this bastard the fuck out of here!"--that was broadcast, reportedly by accident, to the community at large, what happened while Rice was there is in dispute. According to the version advanced by Marvin on his own program and during an appearance the next Monday on KHOW colleague Peter Boyles's morning show, Rice flew off the handle and began screaming into Marvin's face while a commercial break was playing. When it became clear that reasonable discourse was impossible, Marvin demanded that Rice leave, but the mayor refused to do so; he only left, Marvin says, after he heard Marvin describing him to a 911 operator. This part of Marvin's story was quickly seized upon by the folks at Glendale-based Shotgun Willie's Show Club, who put a message on the club's marquee that read, "TO REMOVE THE MAYOR, JUST DIAL 911."

Predictably, Rice's version puts the blame for the quarrel squarely on Marvin. "When I walked into the booth," the mayor says, "I went to shake his hand, but he slapped my hand away and said something like, 'I'm not going to shake your hand, you conniving son of a bitch.'" He adds that Marvin did not let him point out the contrasts between the Glendale and NFLF ordinances. Instead, Marvin threw down a stack of ordinances (an action that apparently switched on his microphone) and, in Rice's words, "started shouting at me, using all kinds of profanity. Now, when you're in that kind of environment, your voice does become more elevated than normal, but I was in no way screaming at him or flailing my arms. The only time I screamed at him was when he really went off on me: I yelled, 'You challenged me to come down here and prove what I was saying, and when I show you that you're wrong, you won't let me on the air, and I don't think that's fair. It's because you can't handle the truth.'" About this last statement, popularized by actor Jack Nicholson in the film A Few Good Men, Rice says, "That would have been a great line if it hadn't already been in a movie."

Off the air, Marvin says his faceoff with Rice has been overblown. But he continues to make sport of the mayor, whom he labels "a flat-out liar," on his show. He has a collection of cartridges on which he's recorded snippets of dialogue, like "Takin' it to the man" (delivered by actor Samuel L. Jackson in Pulp Fiction), and he uses them frequently. But the cart that's his current favorite is one simply labeled "Joe." At the push of a button, it plays Rice comments such as, "I'll prove it to you," "I have no agenda" and "Give me one question at a time" that Marvin uses as punchlines at the mayor's expense.

These jibes are hardly the most serious obstacles confronting Rice. A slightly altered version of the sex-business ordinance was approved by the Glendale City Council on March 17, but Glendale's two strip bars plan to appeal the decision. In addition, Rice's political opponents have formed a committee dubbed the Glendale Tea Party; if they prevail during an April 7 election at which three city council seats are up for grabs, the mayor's ability to turn his ideas into statutes could be severely restricted. But despite all the items on his plate, Rice still isn't willing to forget about Marvin's antics. He has a lawyer examining a recording of the February 27 broadcast with an eye toward taking Marvin to court for slander, and he also wants Marvin to deliver on a $1,000 bet the talk-show host made that the Glendale sex ordinance and the NFLF mandate are identical. Rice has earmarked the money for the Glendale Summer School Scholarship Fund and says, "I expect the check before the start of the summer term."

He shouldn't; Marvin is on record as stating that he won the wager and that the mayor owes him $1,000. This stance frustrates Rice, but it doesn't surprise him. "There are some things that he's said about me that are out-and-out lies, totally without basis," Rice says. "Nowadays in radio, there's a market for that. But I think there's a line that can't be crossed. And he crosses it all the time."

The broadcast visited by the federal cop demonstrates how difficult it is to know which Marvin is going to materialize, and when.

The day's designated subject is a Marvin chestnut: the foibles of President Bill Clinton. Like most of his peers, he is in a lather over allegations of sex between the president and former intern Monica Lewinsky; at this point, only a news conference during which Clinton announced that "Monica and I repeatedly engaged in oral sex, and it was terrific every time" would likely cause Marvin to stop assaulting his veracity. But when Marvin tries to rev up callers about the issue, he discovers that most of them are fresh out of indignation. The conversation drifts to demolition derbies--Marvin has been invited to participate in a crash-and-bash event this summer--and actress Jodie Foster's announcement that she's pregnant. After learning from newscaster Steve Alexander that Foster declined to name a father or discuss the method of impregnation, he asks, "Did she use a turkey baster? A funnel?" He affects an announcer's tone: "The father was vial number 734, which had been loaded into an air gun." In his normal voice, he adds, "Maybe they used the dipstick from a Volkswagen crankcase. Maybe they just dripped it in there."

Such frivolity is short-lived. Within minutes, Marvin is beating the Clinton-and-Lewinsky drum again, and after repeatedly urging listeners to phone in to volunteer their definition of marriage (an institution he says Clinton and Colorado governor Roy Romer have both trashed), an elderly-sounding gentleman finally does his bidding. Rather than expressing outrage at the behavior of Clinton and Romer, however, the caller offers an everybody-does-it argument that he augments by mentioning a decade-old rumor that ex-president George Bush had a mistress.

Marvin, who until this moment has been on his best behavior, changes from an articulate moralist to Ralph Kramden about to send Alice to the moon. Marvin has recently gone down two pants sizes (the reason is stress, he says), but he's still a formidable slab of humanity, especially when enraged. "What's her name?" he barks, his naturally loud voice rising in volume. "You don't know, do you? Well, when it comes to Bill Clinton's mistresses, I know some names. Does Gennifer Flowers ring a bell, oldster? Huh?"

The caller attempts to respond, but he doesn't get much of a chance. Within seconds, Marvin, his eyes dancing, his cheeks reddening, his eyes bulging, his unruly beard flapping, disconnects the line even as he continues to spew his wrath: "Yeah, go collect your Social Security check. Get off the phone, you stupid brain stem."

"Brain stem": It's Marvin's trademark insult, and he's hung it on callers of every conceivable age, color, creed and political persuasion. But this particular storm passes as quickly as it materialized. He returns to the institution-of-marriage motif a few more times, but when it yields diminishing returns, he lightens up, praising the day's segue music (mostly provided by Britisher Edwyn Collins), gushing over KMGH-TV/Channel 7 sportscaster Janib Abreu (when she calls the station, Marvin devotes twenty minutes to her greatness), and comically imitating evangelists Ernest Angley and Benny Hinn endeavoring to heal the deaf. When producer Shannon Scott announces that he's receiving criticism from deaf listeners, Marvin asks, "What do you mean we're getting complaints from deaf listeners? How can they complain when they can't hear what I'm saying?"

During a batch of pre-recorded commercials, Scott tells Marvin that the previous objection was a joke; the caller had offered a politically incorrect impression of a hearing-impaired person, then broken into guffaws. Marvin's round face, which had previously seemed so threatening, glows with delight. "Somebody gets what I'm doing," he says. "Somebody gets it."

Give me an hour a day," Marvin often tells his audience, and he insists that he means this literally. "You've got to listen to me over a prolonged period of time to understand what I'm trying to do. There are people involved in the show, like Steve Alexander and Shannon Scott, who are an integral part of it, and I have other ongoing things, too. And I don't do only one kind of thing. Everybody talks about how I hang up on everybody and call them brain stems, but they never talk about when I raised $6,000 for Skinner Middle School so that the kids there could go to camp, or how Shannon and I saved a dog's life by talking the woman who owned it out of putting it to sleep. My show's like a novel: You have the main plot and then you have subplots--and the subplots change all the time. If you come into it in the middle, you might not understand what's going on."

Such a comparison comes naturally to Marvin, who has serious writerly aspirations. Pieces penned by him have appeared in numerous small political magazines and on computer discs put out by a now-defunct company, Chicago's Spectrum Press, and he's in the midst of seeking a publisher for what he refers to as "an experimental crime novel" --experimental because it has no punctuation. He seems to seek out the edge, then boldly leap over it. "I've always had a fascination with petty criminals, thieves, death and violence," he acknowledges, and Second Skin, a collection of poetry issued by Spectrum in 1996, backs him up. Dedicated to "Charles Starkweather, Joseph McCarthy, Joseph Stalin, and all other small-time punks waiting in the dark," the volume presents stanzas dripping with resentment, gore and guilt. Typical is "Until Sunup":

Thoughts of punching you in the face my fist balled up

my tongue dancing touching and tasting your blood

nibbling at your lower lip ruby red and swollen

salt from your tears of misunderstanding

brought on by something coiled tight and hot

inside me yelling to me to act it out right now

instead I listen to the calm in your voice

grab you and hold you safe again

until sunup

For Marvin, emotions like these can be traced to his youth, which he discusses in terms that reflect years of psychotherapy. He was born in Los Angeles, he says, but for the most part grew up in conservative Orange County, California, where he relocated when he was four or five; he's bad with dates. The move was precipitated by the divorce of his mother, who later was employed by an upscale chain of fashion stores, and his father, Stuart Cohen, a talent agent whose clients included actors Valerie Harper, John Savage, Martin Sheen and Sally Kellerman. Marvin claims to have only one memory left of Cohen: "I remember that he came to the house once over the holidays and looked uncomfortable. After that, I never saw him again." He learned of his father's death in 1975 via a phone call from Harper, who offered to fly him to California from Texas, where he was living at the time, to attend the funeral--"but I couldn't go. I was too mad."

His mother remarried, but her new husband, a building contractor that Marvin has dubbed "Pol Pot," did not become his dream dad. "My stepfather spent every waking hour telling me how stupid I was," he says. "Anything creative I'd do was wrong." His relationship with his siblings--two step-sisters and a half-sister, all of whom he speaks about unflatteringly--was nearly as tortured, he says, and his undiagnosed mental condition ensured that reconciliation was not an option. "I never became especially violent," he recalls. "I'd become moody, or I'd become manic."

By the time he was a sophomore in high school, Marvin was heavily into self-medication. "You name the drug and I did it," he says. "I even snorted heroin. And I drank. I'd do things like going to the dinner table on acid, because I couldn't handle my family. In short, I was just very hostile and didn't fit in--and I hated my household. My mission in life was to get out of there."

Radio salved these wounds. He fell in love with the medium as a kid; he waxes rhapsodic about listening to the late Bob Crane, who was a disc jockey for KNX-AM in L.A. before he starred in Hogan's Heroes. His perspective broadened during his early teens, when he was given a shortwave radio strong enough to pick up Radio Havana. "I fell in love with Cuba and Marxism," he says. "I was probably the only thirteen-year-old in Orange County who could raise his hand in class and tell you who the finance minister of Cuba was."

In 1973 Marvin made a demo tape that landed him a gig playing country music at a station in Del Rio, Texas. But the job was only a pit stop; he skipped from one lousy job to another throughout the decade. During the same period, he married a woman as dedicated to substance abuse as he was, and although the relationship produced a daughter, Rachel, who's now twenty years old and living in Texas, Marvin remained desperately unhappy. Divorce helped, but not enough.

Things improved on the personal front when he met his second wife, Mary, in the late Seventies; they wed two years later. Thanks to her insistence, he gave up drugs and sought medical treatment. While living in Salt Lake City, where he'd moved in 1986, he says he was finally diagnosed as bipolar at what he calls a "Dickensian" facility run by the State of Utah. But his troubles weren't over. "They never got the doses right. Some days my eyes would be like headlights, and other days I'd be drooling. Going through that taught me what a fucking crime health care in this country is. People like Newt Gingrich and Bob Dole and Trent Lott and all these shitheads run around telling us we don't need nationalized health care, but they don't exempt themselves. They only exempt people like me--and back then, I was hanging on for dear life."

When Marvin moved to Florida in 1988, two significant changes occured: He found a doctor who hit upon a prescription cocktail that didn't completely erase his individuality, and he got his first job in talk radio. Before then, he says, he had tried to hide his erratic behavior from listeners and employers. But because tiny WKTN-AM in Saint Petersburg-Tampa had so few callers, Marvin was forced to do hours-long monologues to fill time--and what came out, he believes, was the real Jay. "I could either come in and be a creative character and be a phony, or I could just be myself," he says. "That was my choice--to be a manufactured item or a real human being. And I had no interest in being a manufactured item. I didn't want to be something I wasn't."

In the beginning, Marvin was primarily an ideologue, pummeling Ronald Reagan's America from a leftist perspective. But by the time he'd moved to WFLA-AM, another Saint Petersburg-Tampa station, he says, he'd begun to leaven the politics with humor and anecdotes about his life that dealt with, among other things, his mental condition. Sudden oscillations in his disposition were also part of this package, as they still are, but Marvin feels that they have more to do with his personality than with either his disorder or the drugs he takes for it. He may seem to be out of control at times, but he says he's not. In his opinion, the only time he's lost it on the air occurred in Chicago after he'd sworn off his medication; the next day, he divulges, he tried to kill himself by driving his car into a tree. Since then, he's generally followed his doctor's orders. "I take one Zoloft, two Klonopin, pills for high blood pressure and a diuretic," he says. "It's a pain in the ass taking all that stuff, but I always make sure I do it."

Well, almost always. There are days when Marvin resents his regimen and leaves the capsules and tablets in their containers. On those occasions, Mary, who works as a literary agent (she represents the prose and poetry of Marvin and singer-songwriter Tom Russell, among others), serves as a safety net. If he sounds down and depressed on the air, odds are good that Mary will call and ask if he skipped his medication. And Marvin, who generally brims with bravado, will sheepishly confess that he didn't and promise to do better tomorrow.

Marvin has been on a career upswing since his treatment breakthrough. He had a solid following at WFLA-AM, and after a seven-month detour in Milwaukee, he scored with fans of Chicago's WLS-AM, a talk giant whose signal can be heard in 38 states. When Marvin left WLS to take the KHOW position, rumors circulated that he had been fired, but that's not so. He left on his own after WLS was sold to ABC, a network owned by the Walt Disney Company that he says censors controversial hosts. He gives credit to Jacor Communications, the Cincinnati company that owns KHOW and seven other stations in the Denver-Boulder area, for letting him be himself. Plenty of listeners are pleased by the results: Although Marvin trails KOA-AM's Sports Zoo in the afternoon ratings by a substantial margin, his numbers are big improvements over those of his predecessors, and they keep rising. He won't reveal how much he's being paid by Jacor beyond saying, "I'm not some highly paid radio performer, but I'm managing for the first time in my life to put a little money away."

The growth in Marvin's popularity reflects a modest mellowing in his approach. The Jays heard during his early KHOW broadcasts were much more abrasive than the ones on display now, and reviews in the daily newspapers were caustic. Mention these notices and the cantankerous Marvin surfaces. "They bothered me because they were unfair," he says. "It's unfair to have a guy move his family to a city with the best intentions and then be on the air for only two days before people start writing awful things about him because he's not doing quote-unquote National Public Radio."

By the same token, Marvin does allow that his style is idiosyncratic. Some of his critics have painted him as a radical, and so does an autobiographical paragraph attached to Second Skin, which describes him as "one of the only openly leftist talk show hosts on commercial radio today." But this descriptive is too rigid. He's still enamored of revolutionary Cuba; on the walls of his modest Denver home, he proudly exhibits a framed autograph of Fidel Castro and numerous photos and posters depicting Che Guevara, who he says "was Christ-like." But at the same time, he openly supports Treasurer Bill Owens, a Republican whom political opponents see as a water-carrier for various far-right causes, in the gubernatorial race. Marvin has also been exceedingly kind of late to Denver mayor Wellington Webb; when Webb appeared in-studio with him in late February, softball questions like "When did you first move to Denver?" and "How did you meet your wife?" were the order of the day.

If there's a contradiction here, Marvin doesn't see it. About Owens, he says, "I don't agree with everything he stands for, but I found him to be very candid, very open and not afraid of an argument--and in this day and age, we need that."

As for Webb, Marvin contends that the mayor "has a plan to make this city even greater--and I really like him. I think he's the kind of person who pretty much tells you how it is, and either you like him or you can lump it."

The same goes for Marvin. He may sound dogmatic, but his political convictions are actually as multi-faceted as his psyche--and he's proud of it. "I opposed sending troops into Iraq when I was working in a town [Saint Petersburg-Tampa] that had a military base," he says. "When the Gulf War started, people wanted to lynch me. They even had to call the bomb squad. Then, after that, I supported a police chief who had been accused of being racially insensitive, because I didn't think he did it, and all of a sudden all my so-called liberal friends accused me of being a fascist. But fuck those people. I'm never going to stick to a party line. I never have and I never will. I'll do as I please and I'll think as I please, and if people don't like that about me, I'm sorry."

After a pause, he adds, "Actually, I'm not sorry. I'm not sorry at all."

Marvin has taken some heat from people who might agree with him if he lowered his voice. Last November, after the racially motivated shootings of Oumar Dia and Jeannie VanVelkinburgh, Marvin spoke forcefully against white-supremacy groups and neo-Nazis. But at a November 25 rally dubbed "Hate Not Welcome Here" that Marvin had tirelessly promoted, he was blasted by Rabbi Steven Foster of Denver's Temple Emanuel for helping create a divisive atmosphere. Marvin reacted not by trying to explain himself to the rabbi, but by repeatedly excoriating him on his show. (Foster declined to comment about Marvin for this article.)

The motivations behind other attacks on Marvin make more sense. After Marvin condemned skinheads, unknown people broke his car window, trespassed on his property and poisoned one of his three beloved dogs. The dog, named Papito, survived and is fine, but the incident caused Marvin to redouble his efforts to keep himself and his loved ones safe. After cabdriver Daniel King, a longtime local gadfly known for his support of a ballot amendment supporting the right to carry concealed weapons, made comments that Marvin viewed as inappropriate and later appeared at a restaurant at which he was eating, the host filed a temporary restraining order against him. King admits to having contacted Marvin numerous times in regard to a case in which he was cited by police for trying to get cabbies at Denver International Airport to sign a petition, and King even confesses to suggesting that they engage in a boxing match--for charity, he swears. But he shrugs off the suggestion that he's been stalking Marvin. "He's an Alan Berg wannabe," King says. "And to paraphrase Lloyd Bentsen, I knew Alan Berg--and Jay Marvin is no Alan Berg."

About this, Marvin agrees. Marvin supporters have played up the comparison between their hero and Berg, an outspoken KOA star who was killed in 1984 in the driveway of his Cherry Creek residence by members of a white-supremacist group called the Silent Brotherhood. But Marvin refuses to play along. "I think that's giving me too much credit," he says. "He was much better than I am--much more talented, smarter."

This may be so, but an argument can be made that no Colorado talk-show host, with the possible exception of Ken Hamblin, has riled up Denverites like Marvin has. He's hardly one-dimensional: When he plays obscure tunes from the Sixties to the Nineties, discusses cult movies (he's a big booster of director Jim Jarmusch), recommends books (one recent caller was exhorted to pick up Albert Camus's The Stranger) or makes light of the week's headlines with Alexander--whose newscast was named Denver's best at this year's Colorado Broadcasters Association banquet--he can be hugely entertaining. But the Marvin persona that seems to stick with most folks is the Last Angry Man. Even Mary, who calls Marvin "a teddy bear," says she understands why. He recently asked her something about Bill Clinton and Whitewater prosecutor Kenneth Starr, and when she declined to answer, he unleashed his verbal weaponry against her.

"That's just the way he is," she says. "I had to tell him, 'This isn't your talk show.'"

That altercation ended in laughter--and on this day, so does Marvin's show: The last half-hour is dominated by speculation about how Siamese twins enjoy separate sex lives. As Marvin hands over his headphones to the next host, Sebastian Metz, and heads downstairs, he is exhausted and hoarse, but satisfied. "I'm not perfect," he says. "And I don't want to be hated. But I'm sure as hell not going to lie or be disingenuous just to please somebody. And I'm not scared of losing my job. If I lose it, I lose it. That's life. I'll survive. I think I'm just lucky to be here. With everything I've gone through in life, I'm lucky to be in Denver." After a pause, he says, "Hell, I'm lucky to be alive."

With that, Marvin steps onto the sidewalk in front of the building and heads toward a vehicle parked at the curb. The federal law enforcement officer is behind the wheel, waiting for him.

Visit www.westword.com to read related Westword stories.