Darrell Anderson

Audio By Carbonatix

Dancing has always been a spiritual experience for Cleo Parker Robinson, so it makes sense that she found a home for her company inside a church.

The 55-year-old Denver dance institution has operated out of the Historic Shorter AME Church in Five Points since 1987. More than a hundred years before that, the building was one of the first African American churches established in Colorado. It was destroyed by an arson fire linked to the KKK in 1925 and rebuilt the following year. By the time Parker Robinson moved in, it had been vacant for a few years, had pigeons living in it and needed repairs. Thanks to an agreement with then-property owner Denver Housing Authority, Cleo Parker Robinson Dance was able to rent the building for $1 a year, which allowed the nonprofit to retrofit the church into a dance rehearsal and performance space, then eventually purchase the building in 2021.

Dance companies don’t normally last as long as CPRD has, but CPRD isn’t a normal dance company.

Over the decades, its facility has been used for classes, rehearsals and performances — not just for CPRD, but other local arts organizations as well. “I never thought we’d outgrow the Shorter AME,” Parker Robinson says. “We serve a lot of different communities and arts organizations that use it, and that’s a wonderful thing because it makes it very vital, but we don’t always have access to our own space.”

Now there will be plenty of space for everyone. The $25-million, 25,000-square-foot Cleo Parker Robinson Dance Center for the Healing Arts opened officially on January 17, next to the Shorter AME space, after years of planning and about 18 months of construction. The expansion was funded by a $4 million Community Revitalization grant from Colorado Creative Industries, as well as tax credits and contributions from individuals and foundations.

Kristen Fiore

The building was designed by Fentress Studios, a Populous Company, and constructed by Mortenson. It includes four new dance studios; a big lobby, atrium and cafe area; windows made of electrochromic glass; solar energy panels to power the new facility; an administrative floor; a new state-of-the-art theater with retractable seats, a permanent Marley floor, stage structures built for aerial dance rigging, and more. The expansion doubles the dance center’s capacity; the old space will be used, too.

Parker Robinson is excited to expand the company’s healing arts offerings; that effort has been an important part of her life since childhood. The dance icon got her degree in psychology, education and dance from Colorado Women’s College in 1968, and for decades has built CPRD programming on somatic movement, collaboration with psychologists, and workshops and conferences based in healing.

“You’re using every part of who you are: Your mind, your body, your spirit, your emotions,” Parker Robinson explains. “And therefore, it’s almost like a cleansing. Anything that’s in your mind, anything that’s in your body, gets cleared away for that moment of time when you dance. …It’s such a celebration, of being in the moment, of being alive with someone else. …And when you feel like you’re living, you want to be here, and that’s the healing part.”

She would know.

Dancing Through It

Parker Robinson was born in Five Points, only a few blocks from her dance studio, to a Black father and a white mother in 1948. She remembers her family being followed by the police and having insults thrown at them, but things got even darker when she was ten, and her parents separated briefly. Parker Robinson moved with her mother and siblings to then-segregated Dallas, where her grandparents lived.

“That was traumatic,” Parker Robinson recalls. “I was a child who didn’t understand why the world works like this, why my mother could go certain places and we couldn’t.”

One of the only bright spots was going to church, where her mother was accepted despite being the only white woman there. With the rest of her life so chaotic, Parker Robinson found comfort in the structure there. “It was like choreographing a village,” she says. “You had the children, and the teenagers, and the elders, and the deacons. Everybody had a place.” This would later inspire the choreography for her dance, My Father’s House, and her efforts to open the doors of her dance studio to anyone and everyone.

While in Dallas, Parker Robinson fell ill and her kidneys began to shut down. The local hospital was segregated and turned her away. By the time she was admitted to a hospital, “my heart had stopped,” she says. Doctors suspected she’d spend the rest of her life bedridden, but her parents encouraged her to keep moving.

The family reunited in Denver when Parker Robinson was twelve; by then, she’d become nonverbal from the trauma. “It had a tremendous effect on me,” she admits. “I didn’t know how to talk to anyone about that experience. I couldn’t trust the world. I couldn’t trust my body, how one moment I’d wake up as a healthy child, and the next day I could die. I couldn’t trust anything.”

Playing basketball and kickball helped her start coming back into her body, but she didn’t find her creative voice until she started dancing at her family’s dances, where her father, an actor, and her mother, a French horn player, would invite family and friends to dance around the house. “My father and mother were amazing,” she says. “They encouraged us through dance to clean the house, be a team and talk about what we were experiencing. I could express those inner joys, inner fears, inner anger — anything. And I think that was the greatest gift I could have.”

Kristen Fiore

But she didn’t want to keep it to herself, so she started Cleo Parker Robinson Dance in 1970 at the age of 21. A few months later, her 19-year-old brother, John Whalon Parker, Jr., had a heart attack; a minister, he died suddenly while sitting at the table and reading the Bible. Parker Robinson says the sudden loss left a hole in her own heart, which was already heavy from recent events in the Civil Rights movement, including the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

As she observed her mother and her brother’s pregnant wife from her own grief, she realized that they were all mourning in different ways because they’d had different relationships with her brother. This sparked the creation of one of her masterworks, Mary Don’t You Weep, representing how the three Marys (the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene and Mary of Clopas) mourned Jesus’s crucifixion and the way people gather, grieve, love and help heal one another. It is a dance of sorrow and mourning, but it’s also part of a larger movement showcasing joy and community support.

“When I began to try to heal from all that, it was Mary Don’t You Weep that really helped me,” Parker Robinson says.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day was made a federal holiday in 1983, and Colorado first celebrated it in 1984; Parker Robinson would go on to take Mary Don’t You Weep to King’s alma mater, Morehouse College, in 1986, where it was performed for King’s family, Bishop Desmond Tutu, Jesse Jackson, Dick Gregory, Andrew Young and more for the first official national observance of the holiday.

Kristen Fiore

The Writing on the Wall

Today, Mary Don’t You Weep is preserved via Labanotation (a form of recording choreography) on the exterior walls of the Cleo Parker Robinson Center for the Healing Arts, a powerful emblem for the new facility that’s focused on becoming a spot for the community to gather and heal.

Parker Robinson likens it to “urban hieroglyphics,” but the Labanotation symbols were carefully written out, proofed and approved by dance professors Patty Harrington-Delaney and Julie Brodie; in the age of video, it’s a little-known and tedious way of transcribing choreography. Having it on the building is decorative and educational, but it’s also functional: The Labanotation is set on solar panels that power the new facility.

“We had to work together to make sure the visitors don’t see repetition on the facade, and if someone can read the Labanotation, they won’t see any mistakes,” says Kahyun Lee, the Fentress principal architect and interior designer for the project who came up with the idea after enrolling her son in a CPRD class and becoming deeply curious about dance and how it’s recorded.

Lee was also inspired by the company’s dance Salomés Daughters, which led to the 226 laminated glass fins displaying 55 colors and decorating the exterior of the new building above the Labanotation.

Kristen Fiore

These aren’t the only works of art inspired by Cleo Parker Robinson dances. A larger-than-life Junkanoo Queen was painted on the wall near the new atrium staircase by Denver illustrator and designer Jenn Goodrich. The painting is inspired by the Afro-Caribbean Junkanoo King in CPRD’s annual Granny Dances to a Holiday Drum and bears the names of CPRD donors.

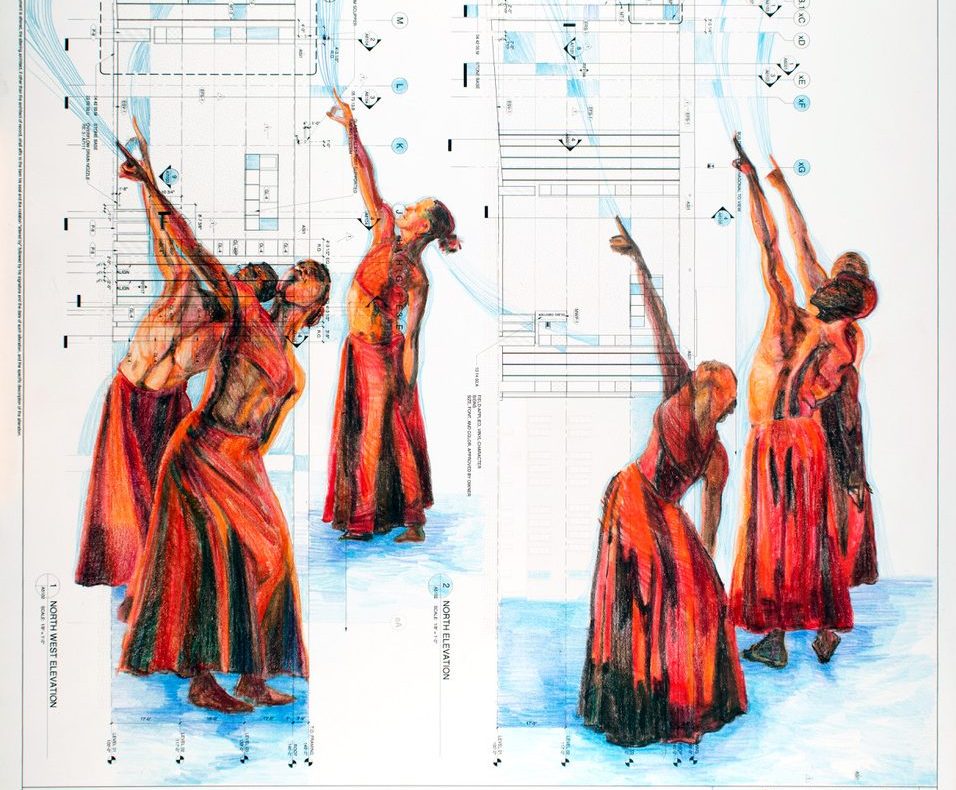

Meanwhile, Darrell Anderson, a well-known Denver artist and longtime friend of Parker Robinson, created three thirty-by-forty-inch colored-pencil drawings on blueprints of the new facility called “Rain Dance Series.” It depicts scenes from CPRD’s Raindance, with dancers moving gracefully in vibrant, flowing costumes.

“A dancer will dance for hours and hours to make movement that turns into music and color, and to land like a feather,” Anderson says. “With construction documents, everything has to be perfect, so you know where things are. So, my attempt was to integrate the two and show some of that process.”

Anderson says the artwork will be hanging in the new facility, which he sees as a powerful gift to the community. “It’s going to continue to make Cleo Parker Robinson an icon,” he says. “It made our community not only fascinating, but powerful. That’s always been my intent with my artwork. I have the ability to express my emotions through a two-dimensional surface, and she can do it with movement and color.”

Bringing in the Heart

Early in the mornings, when the sun hits the colorful glass fins just right, an array of hues reflects on the floor of the new Marcelline Freeman Studio. Later in the day, the 28-foot-tall studio becomes vibrant with dancers rehearsing as sunlight streams in.

The new facility is full of natural light and colors, with different areas color-coded by function: restrooms are orange, elevator areas are yellow and office spaces on the third floor are decorated with purple carpet, because that’s Parker Robinson’s favorite color, Lee says. Viewing windows in the boardroom and Parker Robinson’s office peer into the studios below.

Fentress Studios, which is known for its work on Denver International Airport, the Colorado Convention Center and the Denver Art Museum, as well as major projects around the world, designed each space to be multi-functional. The electrochromic windows remove the need for curtains and help with temperature control. The theater was built underground, which will also aid in temperature control and soundproofing.

Fentress Studios founder Curt Fentress, who first went to a CPRD performance almost fifty years ago after seeing it listed as a free thing to do in Westword, relishes what he calls “The Kiss.” That’s the place between the new building and the historic church, which, as a National Historic Landmark, had to be preserved.

Kristen Fiore

“The building really just kisses the church,” Fentress explains. “It doesn’t support off the church or have any structural connection to the church. It’s supported on columns that are set back from the foundation. There’s a space there, and there’s no chance of interrupting the foundation of the church.”

Mortenson, which has worked on projects including the DAM, Ball Arena and Coors Field, had to make a few adjustments.

“Fentress decided to go with an atrium-style lobby so that you would still be able to see the brick from the exterior, as well as when you walk in, and there’s a skylight that runs across the elevation that really showcases all the existing windows,” says Mortenson’s project manager Tori Vendegna. “…Across the entire elevation, there’s a five-inch expansion joint that runs up the vertical base, along the horizontal and back down the vertical base, so it will allow for any movement as the new building comes into its own and settles a bit.”

It was by no means an easy process, since everything had to fit on a small footprint of only 6,000 square feet. A neighboring dog park had to be demolished, as did the old facility’s annex, which is where its elevator was. For about a year, there was a two-lane street closure outside to give Mortenson more room for construction, which wasn’t ideal since CPRD is across the street from a Safeway.

But Vendegna says it’s been a once-in-a-lifetime experience. “I’ve always thought of a building as being almost like a body,” she says. “I think of the structure as the bones and the exterior as the skin. The interior makes up the insides of your body. But what I’ve really come to find out as they’re moving in their furniture and dancers are having classes is that they are bringing life into the building. They’re bringing in the heart.”

Kristen Fiore

An Invitation

Parker Robinson feels it, too. “The fact that we are connected to the Shorter AME Church, we already feel the ancestors that are in that space and moving into this new space,” she says. “It’s seamless. It’s like a spiral of energy.”

Lee sees the completion of the project as an invitation from Parker Robinson to the Denver community: “She is inviting everybody to come to the new space and telling them, ‘Come here, learn, engage during events and be together.'”

And for Parker Robinson, being together is kind of the whole point. “We’re all looking not to be isolated islands from each other,” she says. “We’re not islands. We’re here collectively. We come alone and we leave alone, but in the middle of all that, we become this larger being, and that’s the potential of working through all our bad stuff.”

Parker Robinson runs the artistic side of the company, while her son, Malik Robinson, followed in the footsteps of his late father, Tom Robinson, to take over the administrative side of the nonprofit. Malik, who became president and CEO of CPRD in 2024, has big plans for the dance institution, many of them related to access. “You can build a beautiful edifice, which this is, but there are still barriers to making sure that it’s accessible to people who are probably most in need of it,” he says. “We want to make sure that we’re providing pathways for those folks to come in, access it, experience it and benefit from it.”

And Parker Robinson’s message for Denver is to come on in.

“I want to fill these beautiful spaces with people of all ages and backgrounds, and have people dancing day and night, and people standing in Safeway or watching us perform from their car windows and coming in to meet new people,” she says. “It’s going to be a mecca for all kinds of creative experiences.”

The official opening and ribbon cutting is at 10 a.m. Saturday, January 17, with activities and tours throughout the day at Cleo Parker Robinson Dance, 2025 Washington Street. At another event on Saturday, January 24, the community is invited to meet teachers and take free dance classes. Advanced registration is required at cleoparkerdance.org.