Chris Rogers

Audio By Carbonatix

Louisville artist Terry Maker says that her work, large-scale and transformative pieces spun from everyday materials into meditations on existence, feminism, and the spaces between known and unknown, is very much connected to her faith.

“I’m a very liberal Christian,” she says, laughing, “which is very important to my walk in life, and my work. So I might compact into a very hard, dense papier-mâché process, both scientific and religious documents. So I might shred a Bible, for example, and then use those shreds and combine them with secular works of science so the two might live together. Like they do, I believe. Once those are conformed, you might see some traces of them — edges, forms, bits of the refuse of the recycled documents — but not enough to know exactly what’s in there. And thereby comes the mystery and the magic of what happens when these things are alchemically made to bring about another world entirely.”

Such is the artistic philosophy behind much of Maker’s work, some powerful examples of which are included in the Robischon Gallery’s new show Ostinatos, which runs through March 21. The name of the show borrows from the musical term for a continually repeated musical phrase or rhythm, and features artists like Maker who utilize repetition in their visual work as well. For a complete list of the artists contributing to the group show, see the Robischon Gallery exhibit page.

“It’s my use of the circle and the sphere, repeated over and over for the physical aspect of it,” Maker explains. Repetition was a major element in Maker’s last show at Robischon, an individual show of her work called Traces.

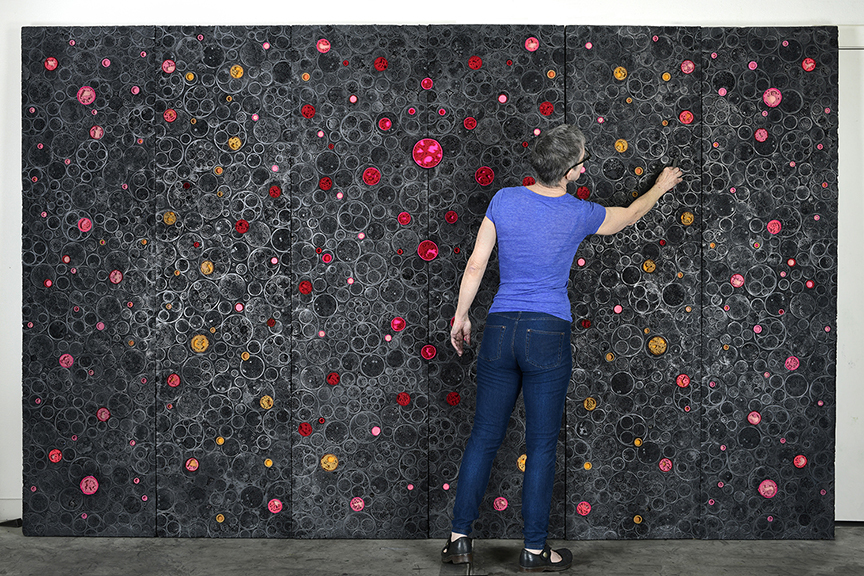

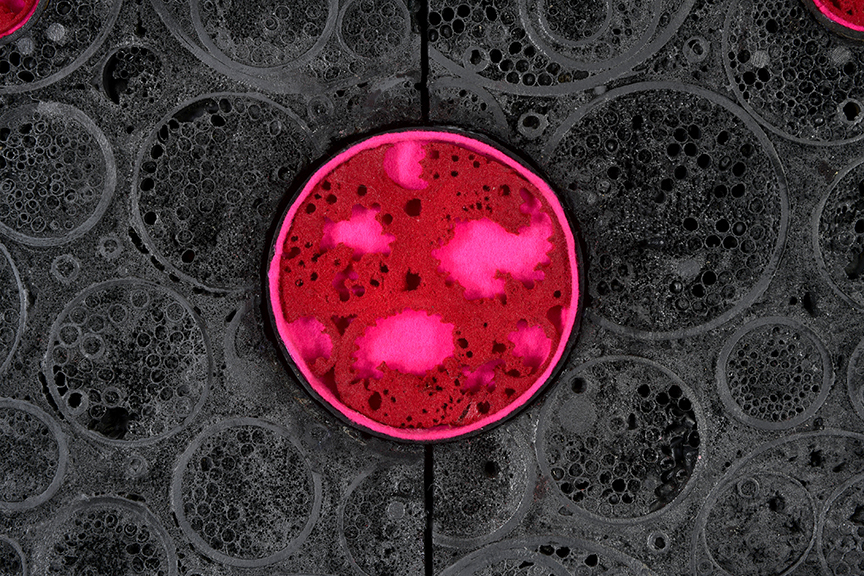

One of Maker’s major works in Ostinatos is “Veil,” a contemplative six-paneled work constructed of thousands of drinking straws in shiny black resin. “It’s teeming with objects,” Maker says, “but what really fills it are the little black voids that threaten to suck the viewer in.” But there are oases amongst the many emptinesses. “There are these various red and gold felted circular forms,” she says, “intended to create a haptic response. The desire to reach for those soft points of brilliance amongst the darkness.”

Chris Rogers

Another of Maker’s pieces in this group show is “Lace Map of the Known World,” which is a network of intricate lines, fissures and voids that may appear fragile up close, but its composition of compacted secular and spiritual shredded documents, foam, thousands of drinking straws, and cast resin elements makes for a hard and sturdy structure undergirding the delicate aesthetic. “The overall illusion is to a Renaissance map,” Maker says, “the kind that attempted the feat of portraying a globe on a flat surface through a surfeit of circles and lines. Sometimes we have trouble finding our way; this is a cartography of the soul, searching to find that better place.”

Much of the act of creation in Maker’s work tends to embrace tearing apart before the reconstruction. “I put my materials through extreme force, such as pressure, cutting, drilling, grinding, and shredding,” she explains. “Then I arrange the matter into abstract composition that hints at space, or the cosmos. In other words, I bury things, and then I kind of resurrect them.”

In terms of theme, some artists begin their process with a specific vision of what they see in their mind’s eye; others jump in and discover the vision as the process takes place. Maker says she does a little of both. “I start with an idea of where I want something to go, and then I take a leap of faith,” Maker says. “Artists have to be really brave, because they don’t know what’s really going to happen. We have ideas, and it’s exciting, and there are hopes and dreams. And then the journey happens, and the art starts to speak, and my consciousness or spirit starts to say, ‘Oh no, this isn’t where this piece wants to go.’ And then you do a dance, and sometimes it’s a really great dance.”

Maker describes herself as both a person and an artist who’s seeking liminal spaces. “These are thin places,” she says, referring to the old Celtic concept, “locations or moments where the veil between the physical earthly world and the spiritual eternal world is exceptionally porous. Liminal spaces are where the divine feels close.”

Which is where the work returns to faith, for Maker. “I think that as artists, we can be conduits of that,” she says. “When we make things, it’s not just a hard and cold thing. It is, I believe, a transmitting of a much more spiritual gift. It’s our journey, our path, and our duty. Especially in this hard world. It comes from something deeper. Even if you’re not religious, there is that gift that we receive. We get to use it and play with it. I truly think that we’re at a point in time we return to that acknowledgement, particularly in the too-often hateful environment we live in today.”

Ostinatos runs through March 21 at Robischon Gallery, 1740 Wazee Street.