Photo by Michael Roberts

Audio By Carbonatix

For movie junkies, the Denver Film Festival is a drug-free speedball that lasts twelve days but whose effects are potent enough to linger for months.

The fest’s 44th annual edition, which wrapped up yesterday, November 14, contained the usual mix of great films, terrible films and those in between. Here are brief takes on the seventeen features I caught (out of 140 total) after the opening-night unspooling of the aggressively lousy Spencer, which I described November 4. The items are largely presented in the order I saw them, but with one notable exception: I saved the best for last.

Red-carpet snapshots prior to the November 4 C’Mon C’Mon screening at the Ellie Caulkins Opera House.

Photo by Michael Roberts

DFF44 was a hybrid festival, with in-person events supplemented by online access to more than fifty selections. And while there were some technical glitches, the Denver Film Festival app allowed attendees to catch films whose screening times conflicted with other stuff they wanted to see. In my case, that included my Thursday, November 4, viewing of director Joanna Hogg’s Archipelago, dubbed by the fest as a “true animated film about invented islands.” The quasi-narrative consists of portentous voiceovers that seem like cutting-room-floor scraps from Last Year at Marienbad, but Archipelago serves as an intermittently interesting compendium of animation styles – rather disconnected, but sometimes gorgeous.

The film I enjoyed far more on that Thursday was Potato Dreams of America, a semi-autobiographical coming-out comedy from director Wes Hurley. The saga follows a kid named Potato who embraces his sexuality after moving from Russia to the U.S. as a boy. The movie had a budget that probably couldn’t cover the cost of a single Spider-Man web shooter, but it’s funny, irreverent (Potato’s imaginary best friend is a woozy Jesus Christ) and ultimately empowering, without the heavy-handedness that often weighs down such projects.

The best part of The Taking, a doc about Monument Valley’s iconic deployment in scads of movies, including several classic Westerns by the late director John Ford, was its introduction. The Saturday, November 6, screening of the film was dedicated to former DFF artistic director Brit Withey, who died tragically in 2019; its director, Alexandre O. Philippe, wrote a lovely paean to his late friend that was introduced by fest co-founder Ron Henderson and read by Withey’s significant other, Ruth Tobias. Too bad the film itself turned out to be less than the sum of its parts, given a format that paired randomly assembled clips with overblown punditry that seldom added much insight.

That’s Denver Film Festival co-founder Ron Henderson in front of the big screen at AMC 9 + CO 10 prior to a screening for The Taking.

Photo by Michael Roberts

Also disappointing was the November 6 bow of Red Rocket, the latest from acclaimed indie director Sean Baker, known for Tangerine and The Florida Project. Baker’s latest focuses on a down-on-his-luck former porn star and dedicated dirtbag, played by Simon Rex, who returns home to Texas to regroup. Rex gives a committed performance, but the story will likely wear out its welcome for anyone who isn’t charmed by redundant scenes of him grooming a hot teenager named Strawberry to become his ticket to a skin-flick comeback.

Fortunately, All These Sons, which I watched on Sunday, November 7, proved much more meaningful. Co-directed by the team behind 2018’s first-rate Mining the Gap, Bing Liu and Joshua Altman, the documentary embedded the viewer in two Chicago programs with the goal of preventing young Black men from becoming gang members and/or homicide statistics. Among the mentors is a man who is making amends after committing a well-known murder during the 1980s, then losing his own son to gun violence. The results are profoundly moving and inspirational, yet Bing and Altman (who took part in an excellent post-screening Q&A) avoid platitudes and easy answers.

Monday, November 8, was marked by France, in which Léa Seydoux, who’s suddenly everywhere (see her in both the James Bond flick No Time to Die and Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch), portrays a celebrity journalist named, yes, France, who begins to unravel after getting involved in a minor traffic accident. The melodramatic shenanigans seldom make much sense; director Bruno Dumont doesn’t appear to have much interest in paying off storylines (a tragic auto crash is essentially a casual throwaway) or maintaining consistent characterizations. But at least Seydoux is a fascinating camera subject who can look breathtakingly perfect or strangely flawed in the same shot. If only she’d been given more to do than cry, which she did more often than Meryl Streep has in her entire career.

A far better effort from the same country was director Jacques Audiard’s Paris, 13th District, which graced the screen Tuesday, November 9. Filmed in luminous black and white, the narrative concentrates on three millennials traveling the same bumpy road to romance but with some surprising detours along the way. Memorable turns by stars Lucie Zhang, Noemie Merlant, Makita Samba and talented rocker Jehnny Beth, as a cam girl named Amber Sweet, are set aglow by a vibrant aura of exploration and discovery.

The thrill of this experience was tempered later on the 9th by The Siamese Bond, which I watched online. Director Paula Hernández draws strong performances from Rita Cortese and Valeria Lois, as a mother and daughter who take a journey together to check out some apartments left to the latter by her late father, and there’s some spicy banter at times. But Clota, Cortese’s character, never develops, and becomes increasingly tiresome during a seemingly endless bus ride that left me feeling as trapped as the figures on the screen.

The first selection on my agenda for Wednesday, November 10, was Stanleyville, which I viewed online. The Canadian production, directed and co-written by Maxwell McCabe-Lokos, has a premise with a whiff of Squid Game about it: Five quirky contestants compete in a game that turns out to have life-and-death consequences. But in this case, the prize isn’t escape from mountains of debt and existential desperation, but a habanero-orange compact sport utility vehicle. The absurdism that follows is neither especially amusing nor gripping in the slightest. As the credits run, most viewers will think to themselves, “How odd,” and then forget about Stanleyville forever.

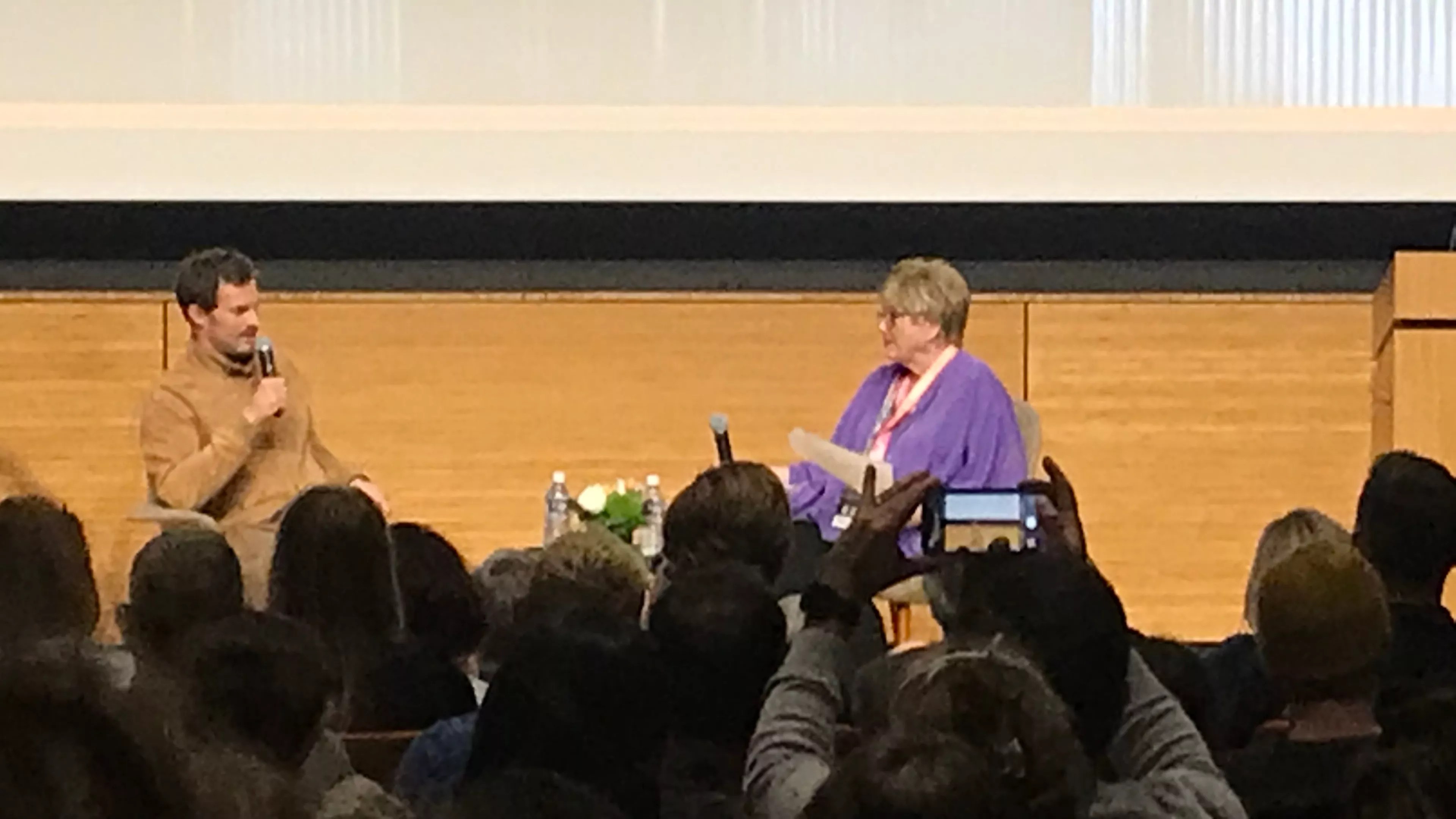

Jamie Dornan during a hilarious Q&A with Sheila K. O’Brien at the Denver Botanic Gardens.

Photo by Michael Roberts

That evening was also highlighted by the fest’s biggest star-get: Jamie Dornan, the sort-of title character from the unintentionally hilarious Fifty Shades of Grey series, who headlines Belfast, a semi-autobiographical effort by writer/director Sir Kenneth Branagh. The event took place at Denver Botanic Gardens’ new theater, and even before the lights went down, plenty of laughs were generated by a Q&A with Dornan conducted by Sheila K. O’Brien, the woman behind the fest’s spotlight on Irish and U.K. cinema, who was as casually unfiltered as your funniest aunt after her third martini. She confessed to getting hot and bothered at the sight of Dornan in the fine mini-series The Fall even though he spends most of his time killing females, tried to goad him into singing (he gave the request a hard pass) and kept pressing for a funny anecdote from his career until he finally acquiesced. He revealed that Dame Judi Dench, who plays his mother in Belfast, has hated going to the movies ever since being traumatized by Bambi as a child.

The movie itself, another flick mainly filmed in black and white (but with a few Wizard of Oz-like transitions to color), was set during the late 1960s, when the differing worldviews of Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland exploded into violence shorthanded as “the troubles.” Branagh contrasts these incidents with bucolic family scenes involving his nine-year-old surrogate, played in sitcom-like style by young Jude Hill. This juxtaposition results in something of a curiosity – an amiable portrait of an ethno-nationalist conflict in which no one ever seems to be in that much danger and escaping the mess is just a bus ride away. It looks great (visually, this is Branagh’s best film), as do Dornan and company do, and the score, filled with Van Morrison tunes, could hardly be more winning. But while Belfast proves an agreeable experience, it’s also a thoroughly lightweight one, especially given the subject matter.

Thursday, November 11, brought another celebrity to the Ellie Caulkins Opera House: Clifton Collins Jr., one of those actors whose face is better known than his name (he was in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, Ballers, Veronica Mars, Westworld and more). But that could change with Jockey, in which the frequent supporting actor takes center stage as an aging rider who is dealing with a health crisis when he learns he may be the father of a track up-and-comer. The film is very much an old-style indie: earnest and sincere (sometimes painfully so), with virtually no irony. It’s more admirable than memorable, but Collins deserves the Oscar buzz he’s receiving thanks to a performance that undercuts the script’s creaky elements with naturalistic simplicity.

Jockey star Clifton Collins Jr. raises an eyebrow outside the Ellie Caulkins Opera House.

Photo by Michael Roberts

During a post-screening conversation with former Denver Post film critic Lisa Kennedy, Collins expressed his appreciation for being given the festival’s annual John Cassavetes award by proving that he actually knows and prizes the work of the bauble’s late namesake. In addition, he talked about the challenges of shooting Jockey on a budget so microscopic that the film, which is ostensibly about horse racing, doesn’t actually depict a complete race, instead showing Collins in tight close-up. The whole thing was done on a twenty-day schedule with a crew of just ten people.

I started festing virtually on Friday, November 12, by accessing Try Harder! online, and I’m glad I did. The documentary explores the pressures on members of the student body at Lowell High School in San Francisco, a majority Asian-American institution (one pupil calls it “Tiger Mom central”) whose attendees are single-mindedly focused on getting into the nation’s top colleges. Because Lowell has an extremely selective admissions process, the majority of students are academically extraordinary, but that only makes it more difficult for individuals to stand out, and aspirants of Asian descent must deal with a particularly virulent form of racism; their achievements can be downgraded because they’re viewed as what a teen commenter describes as “grade-grubbing A.P. robots.” Director Debbie Lum draws out her subjects with curiosity and great compassion while taking the time to remind us that beneath it all, these exceptional young people are still just kids.

Friday’s second feature was ClayDream, whose fest summary describes it as a David vs. Goliath story in which the late claymation pioneer Will Vinton is pitted against Phil Knight, the Nike gazillionaire who ultimately took control of the former’s company and handed the reins to his son, Travis Knight. But the portion of the film dealing with the ways in which Vinton invited a shark into his pool and wound up being swallowed by him is just an episode in what is actually a soupy doc about Vinton’s failed attempt to turn himself into the next Walt Disney. Problem is, Vinton’s biggest claim to fame was a California raisins commercial in which the wrinkled snacks played “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” a curio that really hasn’t aged well. Moreover, the younger Knight transformed the studio he was handed into Laika, whose filmography, exemplified by Coraline and ParaNorman, is much more impressive than anything Vinton turned out.

Saturday, November 13, began with an early-afternoon Ellie Caulkins red-carpet presentation of Torn, a National Geographic documentary inspired by the life of Alex Lowe, who was widely regarded as the planet’s best mountain climber prior to his 1999 death in a Tibetan avalanche. But the project has a much greater goal than simply lionizing a lost thrill-seeker. The director, Alex’s eldest son, Max Lowe, was ten when his dad died, and he fills the movie with searing interviews of his younger siblings, Sam and Isaac, his mother, Jennifer, and her second husband, Conrad Anker, who lived through the avalanche and found his life’s purpose, and enduring love, while working through a fierce case of survivor’s guilt. The offering becomes, in essence, an anti-adventure film that examines with unblinking honesty the struggles endured by those left behind when a superhero falls.

A North Face executive interviewed (second from left to right) Max Lowe, Jennifer Lowe-Anker and Conrad Anker after the Denver Film Festival screening of Torn.

Photo by Michael Roberts

The psychological force of Torn was felt by the audience and participants alike. Max Lowe, Jennifer Lowe-Anker and Conrad Anker were on hand to take part in an interview after the film was over, and while introducing them, Denver Film CEO James Mejia had to stop twice to get his emotions in check. The three interviewees had equivalent moments that drove home the inadequacy of the term “closure.” Raw, moving, beautiful.

Oh, yeah: Crying in a mask sucks.

At the opera house that evening, the closing-night opus was King Richard, about Richard Williams, who gifted the sporting world with a couple of its most intriguing figures: his daughters, tennis superstars Venus and Serena Williams. Because it’s an authorized biography (the Williams sisters are among its executive producers), director Reinaldo Marcus Green and screenwriter Zach Baylin resist casting a too-critical eye on Richard; the occasional accusations that he was a huckster and a self-promoter bounce right off. But the pair succeed at shaping the yarn into a genial crowd-pleaser with more than a little help from star Will Smith, whose trademark likability hasn’t been this laser-focused in years, plus charming performances by Saniyya Sidney and Demi Singleton as Venus and Serena. And then there’s Jon Bernthal, whose version of comic exasperation while portraying coach Rick Macci would have been perfectly appropriate for Cannonball Run.

Like King Richard, Bernstein’s Wall, a documentary about the late composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein at the Sie FilmCenter on Sunday, November 14, was made with the participation of family members. But director Douglas Tirola delivers a more fully rounded look at his central figure. Because he uses vintage recordings of Bernstein, one of the most media-savvy figures in the world of classical music during the twentieth century, as narration, Tirola only touches glancingly on the homosexuality he hid from the public. But he digs deeply into Bernstein’s inability to follow up West Side Story with a hit of equivalent magnitude, and there’s a fascinating section on the blowback from a party he hosted for the Black Panthers that author Tom Wolfe witheringly satirized in what became an important episode from the book Radical Chic. The latter section is spiced with excerpts from White House tapes in which President Richard Nixon repeatedly rips the unapologetic liberal. No doubt Bernstein would have loved hearing every minute of them.

As for my top film at this year’s festival, I am absolutely shocked to reveal it was C’Mon C’Mon, which got the Ellie Caulkins Opera House treatment on Friday, November 5. Why? It stars Joaquin Phoenix, who specializes in my least favorite form of acting – the kind that’s so broad you can see it from outer space – and was hyped by previews that made it seem like a trite lesson in how children are our future. But writer-director Mike Mills’s look at a radio journalist who reluctantly agrees to care for his nephew (Woody Norman) while his sister (Gaby Hoffmann) helps her ex-husband navigate a mental health crisis subverts every possible expectation, including mine about Phoenix. He gives a performance that’s warm, subtle and clear-eyed. Hoffman is just as good, and Norman is a pint-sized miracle: Either Mills did an incredible job of drawing him out, or he’s the most preternaturally gifted child actor I’ve seen in years. Moreover, he trusts the intelligence of his audience in ways that directors such as Spencer‘s Pablo Larraín clearly don’t, and the rewards of this approach proved very rich, indeed.

I left the theater after C’Mon C’Mon feeling both overwhelmed and dumbfounded that the effort had been infinitely better than I’d anticipated. That’s why we go to the movies – and why I love the Denver Film Festival.