Edward Simpson

Audio By Carbonatix

Chicano tattooing has an undeniable power in American imagery.

“I feel like how far it’s gained traction shows how popular and accepted Chicano culture has grown across the country and globally,” says Santiago Padilla-Jaramillo, a Denver tattooer. “Now there are a lot of people in Denver trying it out with their own style. There’s a lot of professional shops and a lot of people who are self-taught who have studios.”

The origins of Chicano tattooing go back to the Pachuco counterculture of the 1940s and ’50s. Under the burden of a long history tied to discrimination, segregation and mass deportation of Mexican American citizens, young Latinos latched onto a vibrant means of self-expression that found conduits through zoot-suit fashion, fast nightlife, gangs and jazz. The subculture also created a space for tattoos, first emerging in the shape of the Pachuco cross, a design typically stabbed with a sewing needle dipped in India ink.

As Pachuco culture declined in the 1960s, the Chicano movement began, and the style was further developed in prisons as a means of self-expression and trade. Tattooers would use a single needle, producing body art with fine lines, intricate shading and high contrasts of black and gray.

Denver’s community of savvy tattoo artists maintains the art form today, perpetuating the imagery of Chicano communities while cracking through perceptions of what it can be. These artists bridge the gap between folk art and fine art in an expression that is its own slice of Americana.

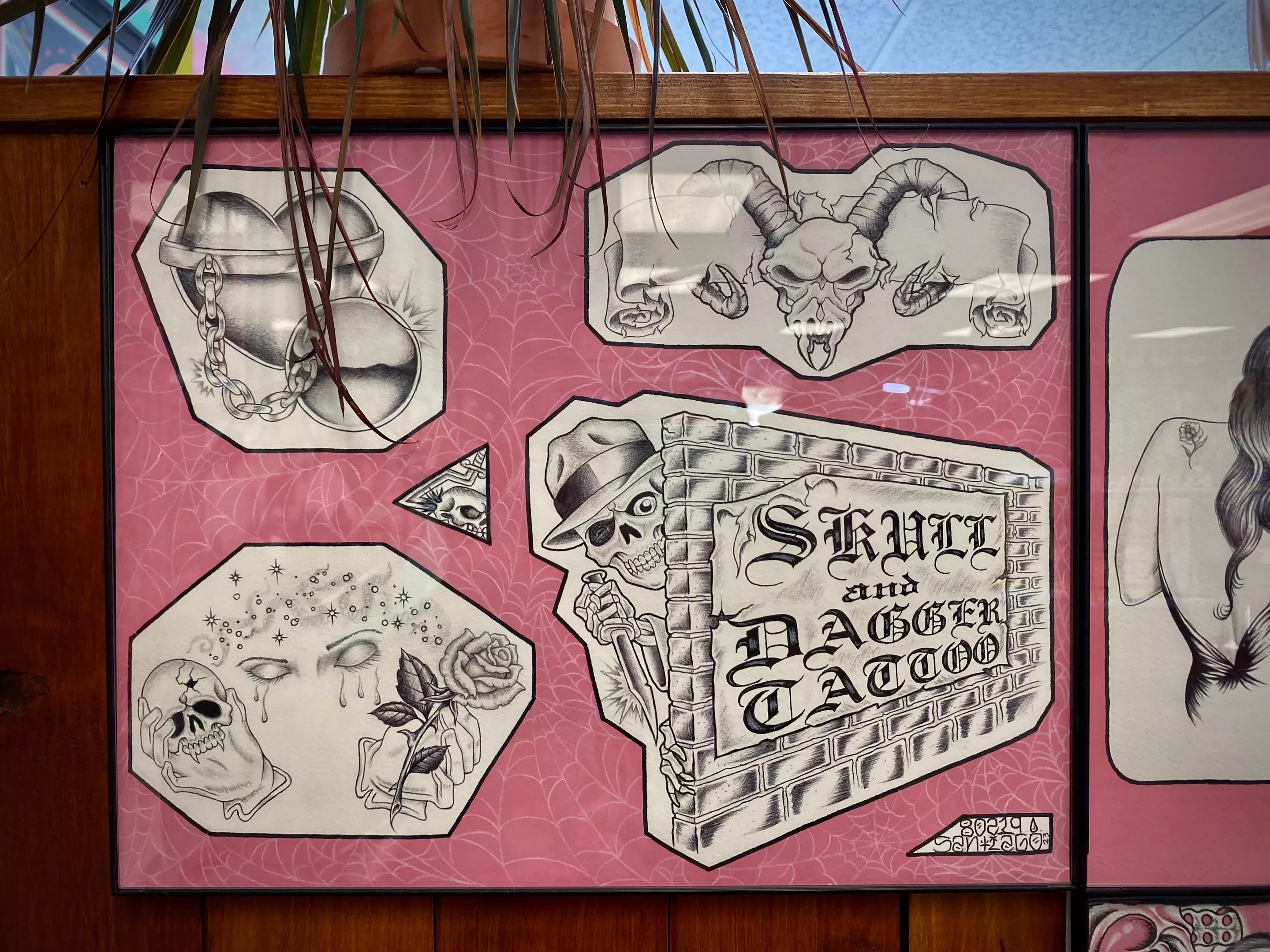

Santiago Padilla-Jaramillo sitting at his station in Skull and Dagger Tattoo Co.

Nicola Huffstickler

Padilla-Jaramillo co-founded Skull and Dagger Tattoo Co. in Littleton in 2023, and has a wealth of knowledge about Chicano art and its influence on the Denver area. Raised in south Denver, he says that his ties to community drive his tattooing.

“My introduction to tattoos was my dad. He was very covered. I remember there were a few times he visited me at school when I was five or six, and all the kids would ask me about his tattoos,” he recalls. “He got tattooed by a guy named Thomas the Priest. Some of the first tattoos I saw [were] done by him.”

His father instilled an unabashed love for art and fringe culture in his blood. “He would be working on five different paintings, and he’d have references sprawled out everywhere,” Padilla-Jaramillo remembers. “My dad has always been a radical person. He grew up in the punk-rock scene in Denver and was pretty heavily involved in that. He was always going against the grain.”

Tattoo flash by Santiago Padilla-Jaramillo

Edward Simpson

Although there weren’t a lot of shops known for Chicano tattoos when he was younger, there were a few individuals creating designs that stood out, says Padilla-Jaramillo: “Chuco Estilo, Gordo Ink…then another guy named Hector Huerta. These are guys I’d see most of the people I grew up with getting tattooed by. Anyone with really nice Chicano tattoos, they were from these people.

“As I ventured out, I started to see some other [local] tattooers like Lorenzo Baca,” he continues. “There were also some guys that I grew up with that tattooed out of their house. I don’t know if I want to put their names out there, but they were out of a project on Kentucky and Irving, and there were a lot of really nice tattoos.”

The first time Padilla-Jaramillo put a needle to skin was at the early age of fifteen. However, he doesn’t acknowledge that as a true credit to his résumé. Now 29, he says he was only tattooing as a hobby until he made the conscious decision to devote himself to the craft five years ago. Since then, he has shown his work in such spaces as the popular Desert Rider exhibit at the Denver Art Museum in 2023.

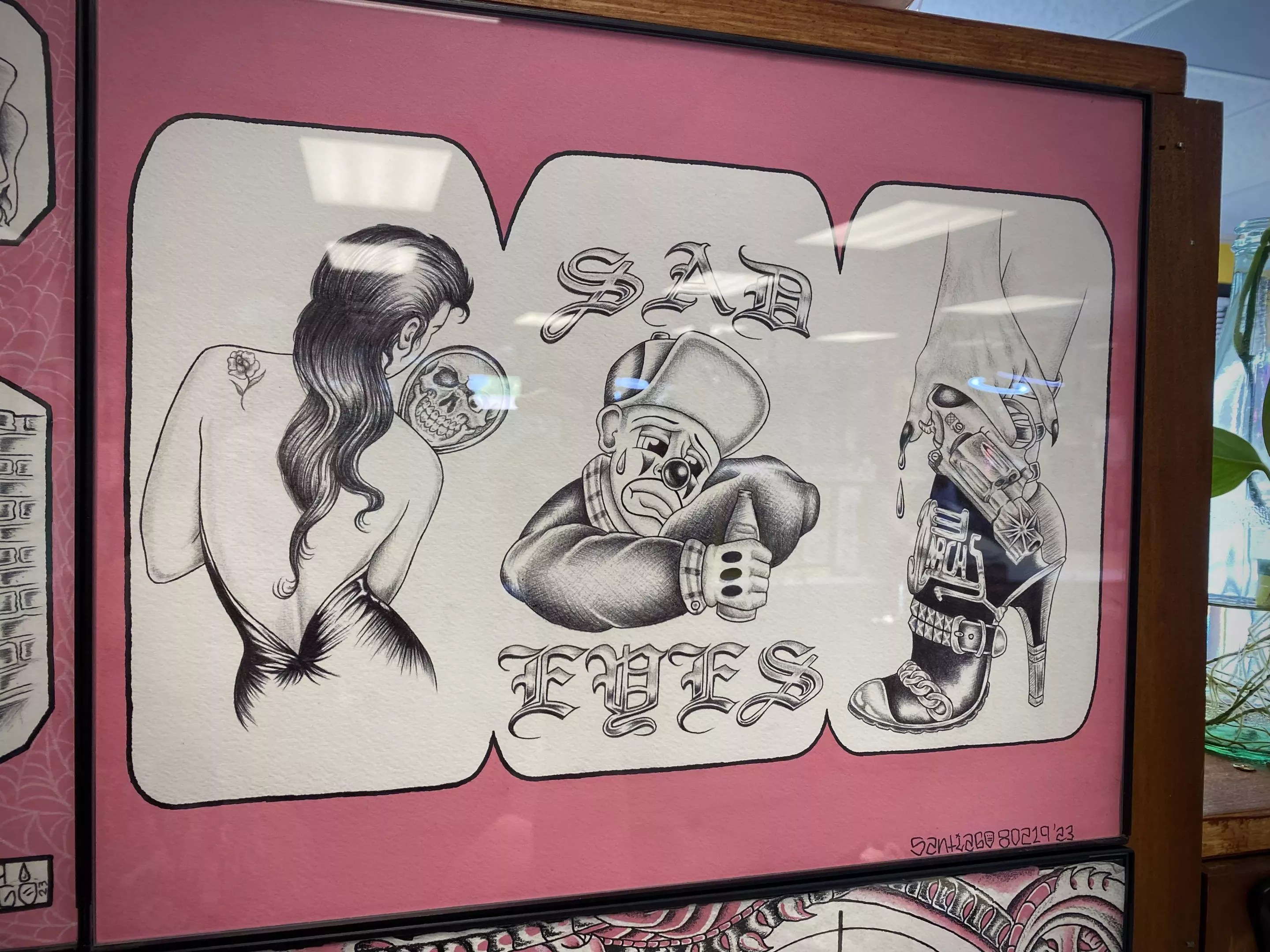

A Sad Payaso by Santiago Padilla-Jaramillo

Edward Simpson

He describes a “reflection of duality” as a common theme in Chicano art: “I feel like we’re a passionate people, so when we feel things, we feel them greatly. When I talk about duality, you look at the images, and some can be beautiful, but they may also contain imagery that makes you uncomfortable, facing a reality where people are in prison or projecting some trauma from their life. I feel like that’s why the ‘smile now, cry later’ [theater masks] is one of the biggest images in what we do, because it shows both sides.”

“Nothing is more important than your ride, your ruca [girlfriend], and your rola [music],” Padilla-Jaramillo remembers hearing as a kid. These themes repeat like a trinity of Chicano culture, serving as strong reminders of what is held close.

When asked what impact he hopes to leave, the sentiment is heartfelt. “I want people to look at my work and see someone loved it,” he says. “I want them to love it, too.”

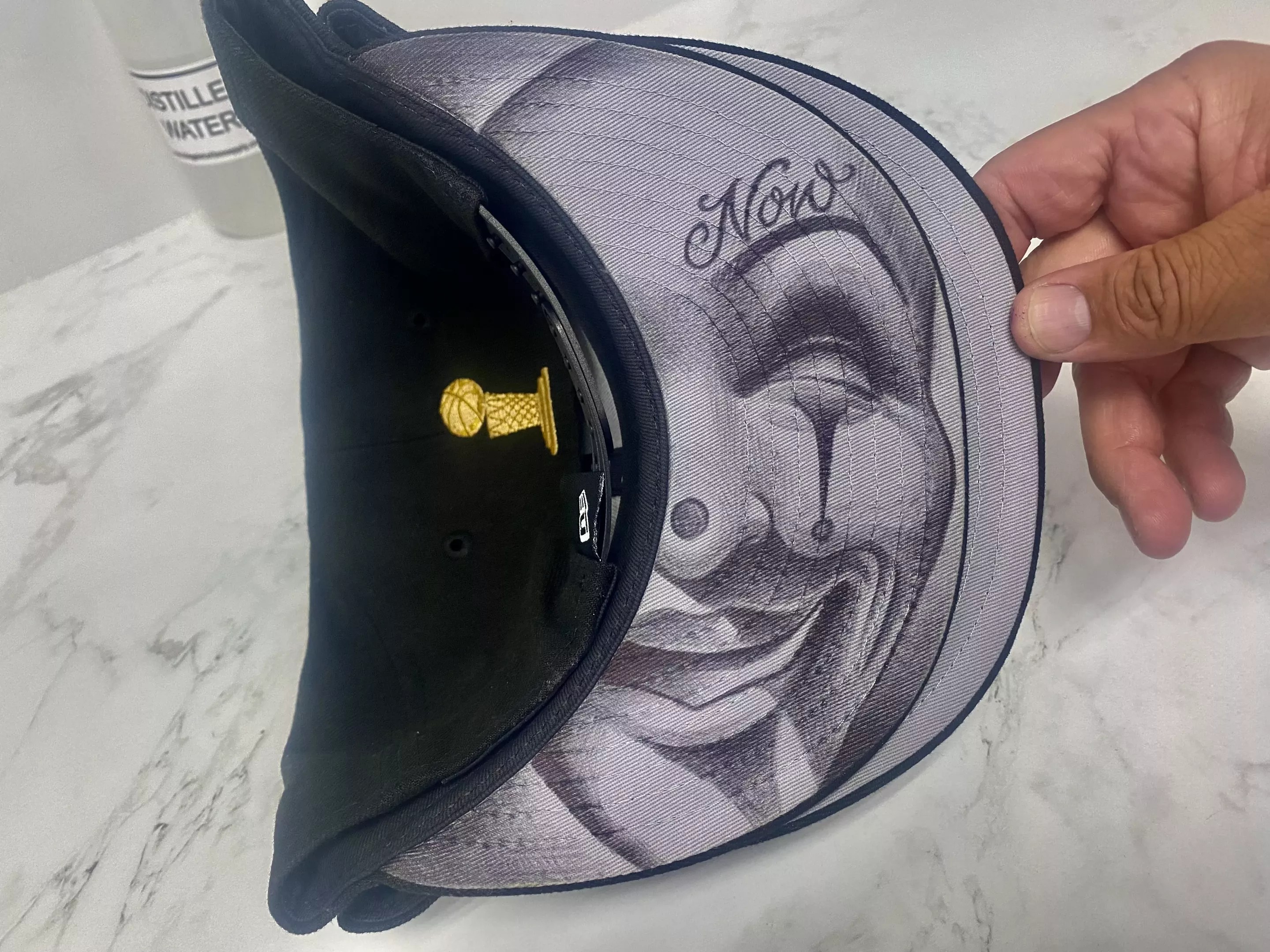

A comedy mask on a hat by Artis Garcia.

Edward Simpson

Artis Garcia, owner of Ben Franks Tattoo Co., is another tattoo artist from Denver who has witnessed Chicano tattooing’s popularity boom. “Tattooing was just another medium,” Garcia says of his overall artwork. He never imagined the potential it could hold. It has afforded him opportunities to travel the world, share his work at conventions and collaborate with artists on an international level.

He remembers tracing vehicles off different pages of lowrider magazines at a young age, and his interest in art progressed naturally. “Fifth grade is when I discovered graffiti,” Garcia recalls. His first introduction to tattoos was through people who wore them home from prison. “There was no Mexican American representation in the Denver tattoo scene at first.”

He did tattoos at parties, growing his skill set through the live wire of nightlife. “You’d go to someone’s house and ask them, ‘Hey, your mom or sister got a hair dryer?’ And that would be the motor,” he says. “Then you’d use a pen or guitar string as a needle. You’d get the guitar string and cut it.” While people waited, they would “use a nail file and sharpen it” so it didn’t hurt as much.

However, like anyone trying a hobby for the first time, Garcia experienced growing pains. “I did my first one when I was fifteen, but it was terrible. I was so bad and I knew it, so I stopped,” he says. “Twenty-one is when I was like, ‘Let’s try it for real this time, because last time it didn’t go so well.'”

Luchador love at Skull and Dagger Tattoo Co.

Edward Simpson

It wasn’t until he met Butchy James, a now-deceased tattooer from Denver City Tattoo Club, that Garcia was able to receive some formal training. “I met Butch when I was in a shop [Preying Mantis], but there was a lot I didn’t know about tattooing the right way. We just became friends, and he was like, ‘Hey, man, as a friend I want to tell you, you gotta redo some shit,'” he says.

“He started me from the beginning doing small tattoos, traditional stuff, building me up. He used to say, ‘Once you know the rules, now you can break them,'” Garcia adds. “Butch taught me it was a lifestyle. He used to say, ‘We are pirates.'”

As times have changed, so have the reasons that people get tattoos. “More people used to have a desire to represent with the tattoos they got. It was to show where you’re from or to keep something close you held dear, but tattoos have become more of a fashion choice today,” Garcia explains. He’s happy to do whatever a customer wants, though: “Sometimes, someone just wants a girl.”

Chicano art is always evolving. In that evolution, Garcia is happy to find new ways to explore the medium. For example, he reimagines the tradition of drawings on handkerchiefs, also known as “paños.”

“It was a prison thing. They’d get them in prison and draw on them and send them home. They’d wear them or hang them out their back pocket. My new thing is I do hats or shoes with a ballpoint pen,” he says.

Today, Garcia is forty, with a fully developed set of skills and a thriving business. But for him, tattooing is not about notoriety.

“I’m not interested in leaving a legacy. I care about making sure people have tattoos they like, leading with an example of passion and fostering a community of appreciation,” he says. “I don’t care about anything else. Me and the person sitting in the chair, that’s what matters. I want to make sure we both like it.”