Joel Long

Audio By Carbonatix

Between a tiger and a hawk is a bolt of lightning red as rage, electrifying the water.

“This is sick,” I say while staring at a struggle between the heavens and the earth.

“You like it?” Joel Long asks me. “Hell yeah, man,” I reply.

“You can have it.” He takes the silk scroll off the wall, rolls it up, and hands it to me with a spirit of generosity that’s partially responsible for the spread of irezumi (the Japanese word for “tattoo,” meaning ‘to insert ink’) throughout the Front Range and the rest of America.

When news happens, Westword is there —

Your support strengthens our coverage.

We’re aiming to raise $50,000 by December 31, so we can continue covering what matters most to this community. If Westword matters to you, please take action and contribute today, so when news happens, our reporters can be there.

Roar of the Sky by Joel Long

Joel Long

Japan’s history has flirted with the acceptance of tattooing since the end of the Edo period (1603-1867). Outlawed in the Meiji period (1868-1912), once Japan opened its borders, tattooing was forced underground, where it became associated with criminal elements such as the Yakuza; tattoos still have an air of taboo in present-day Japan. However, sailors and tourists enjoyed the art form, and the demand grew as designs migrated overseas. In a paradox of censorship, the art flourished. Joel Long operates Floating Picture World, a store of silk scroll prints and original paintings, while tattooing out of Bolder Ink in Boulder. Bruce Michael

Tattooing wasn’t legalized again in Japan until the end of WWII in 1948, when the Allies occupied Japan. With an open world, artists like Kazuo Oguri (Horide) and Norman Keith Collins (Sailor Jerry) began a collaboration that fostered the mutual evolution of Japanese and American ink. Today, tattoo artists still find inspiration in Japan’s rich archive, adopting designs for clients of all backgrounds. In that pursuit, they balance a responsibility to protect the heritage of Japanese tattooing while furthering its proliferation.

Sam Yamini founded Dedication Tattoo in 2013, and he brought a style of Japanese-inspired tattooing to Denver that’s magnetic and bold. “I started tattooing in 2001, and back then, there were very few people that specialized in anything. We weren’t globalized like we are now. The only exposure to other tattooing you got was through tattoo magazines,” he remembers.

Yamini’s foray into Japanese tattooing began in Texas. “I moved to Dallas and started working at a shop where one of the guys did large-scale Japanese tattooing on a regular basis,” Yamini remembers. “As I started to see it, that was it. It was timeless. The best tattoos are not attached to a trend.” They crash through society like waves, year after year, eroding the barriers between cultures.

History serves as the momentum carrying Japanese tattooing forward. “Tradition is about doing something for a specific reason, not just the way it looks. It’s important to acknowledge where something came from and show as much respect to it as you can,” he continues. “That perspective isn’t always consistent. A lot of people just see it as a tattoo, and they’re happy to make adaptations to it.”

Sam Yamini Tattooing a Koi Fish.

Edward Simpson

Yamini says he tries to follow tradition as closely as he can. “There is a correct way, but we ultimately do what the client wants,” Yamini explains. “The imagery does have significance, so it’s not as simple as getting a flash tattoo off the wall. Consistency is an important part of the logic behind the imagery. For example, you won’t typically split seasons across a bodysuit. A whole piece would be one season.”

Everything has a place, and each element of a tattoo adds to its story. Yamini helps set this expectation for each of his clients. “If you want a full bodysuit, you want your back done first. Everything starts off the back and wraps around to the front. So if you get your arm done first, you don’t want it to impact what you get later.”

Yamini is a conduit for dreams. “People are looking for empowerment and self-actualization in every respect,” he says. “They’re looking to change their body with a meaning or a message. They’re choosing a deliberate path, suffering, paying for it. All of these bring a sense of accomplishment, whether that was a goal or an unintended consequence.”

In that service, he’s solidified his place. “For me, it’s more about being connected to something bigger than myself that spans the test of time.”

Dave Regan is a local tattoo artist with a practice that specializes in Japanese-inspired work.

Dave Regan

Dave Regan is another local tattoo artist with a practice that specializes in Japanese-inspired work. He’s also a journalist, illustrator, and author of several books, including his most recent release, Hormino: A Western Perspective, published by Afterlife Press. He runs Tradition Tattooing in Arvada, offering a strong interpretation of Japanese tattooing with occasional hints of an American traditional influence. Each tattoo is a sword with firepower. “What I saw with Japanese work that I loved is that it has a narrative,” Regan says. “It offers people the opportunity to explore grandiose stories.”

Borrowing from that library comes with a cultivated respect. “As a Westerner, you’ll get to a certain level, but you’ll never get higher if you don’t learn the language or travel,” Regan says. Even so, he acknowledges, “There’s something about it that feels disingenuous, but I do travel. I do study Shinto, Buddhism and garden. It doesn’t make me an authority. But it does give me a perspective.”

Regan stays malleable with an active presence in the Rocky Mountain Bonsai Society. “To me, the missing link for Westerners is nature. I get more out of shutting up and sitting in a garden for eight hours rather than sitting in a tattoo shop staring at dragons for 8 hours,” he says. “Getting into the garden work changed me completely. The custodial nature of what we do improved me as a tattooer. My job is to study the space and make improvements where I can.”

Primarily, Regan is trying to maintain harmony. “Horimono [a bodysuit] is what you want for yourself, or what you want for the world around you. There’s not a lot of memorial or attachment to the past,” he notes. “The biggest limitation as a client is expecting a specific result. Nobody knows what they really want. They just know they want a tattoo… The best result requires freedom.”

A Back Piece by Sam Yamini

Sam Yamini

This hinges on a relationship between the artist and the client. “Everybody gets the tattoo they deserve. Each session is an exchange of energy,” he says.

Regan hopes the tattoos help people grow and learn more about the culture. He remembers his mentor and the impact he had on him. “Joel [Long] is the reason I do this,” he says. He’s been a huge part of my life and an influential part of my work. He helped me see what my work could be.”

Presently, Long operates Floating Picture World, a store of silk scroll prints and original paintings while tattooing out of Bolder Ink in Boulder. “I’ve been at this shop for roughly 23 years,” he tells me. He also shares the space with his apprentices, Francesco Arlotta and Graham Scott, a new generation of tattooers perpetuating the art form.

“There’s this mythological buffet. The look is very different and special. It hits you. Not everything does that,” Long shares.

His approach is a vetting of the individual, a hunt for details to weave into the piece. “If they talk a lot, give them two dragons with mouths open. If they’re quiet, I might keep the dragon’s mouth closed,” he remarks. But the hunt doesn’t always reap a bounty. Long works on instinct. He states the truth plainly. “Sometimes I have to turn people away. I’m proud like that.”

Of the figures people get tattooed, he mentions warriors, tigers, angels (karyÅbinga), and various creatures of heaven and hell. However, amongst an expanse of options, he admits his niche. “A lot of my specialties are tigers, dragons, hawks, occasionally warriors… A lot of people say that tigers are my specialty.”

Every work is a canvas containing multitudes of explosions. “It’s in the shapes that you use,” he says of his style. “Plus, when you tattoo, you operate with certainty. One line in, one line, one line. You have to be assertive and definitive. Everything’s everything and nothing’s nothing, and nothing’s everything and everything’s nothing.”

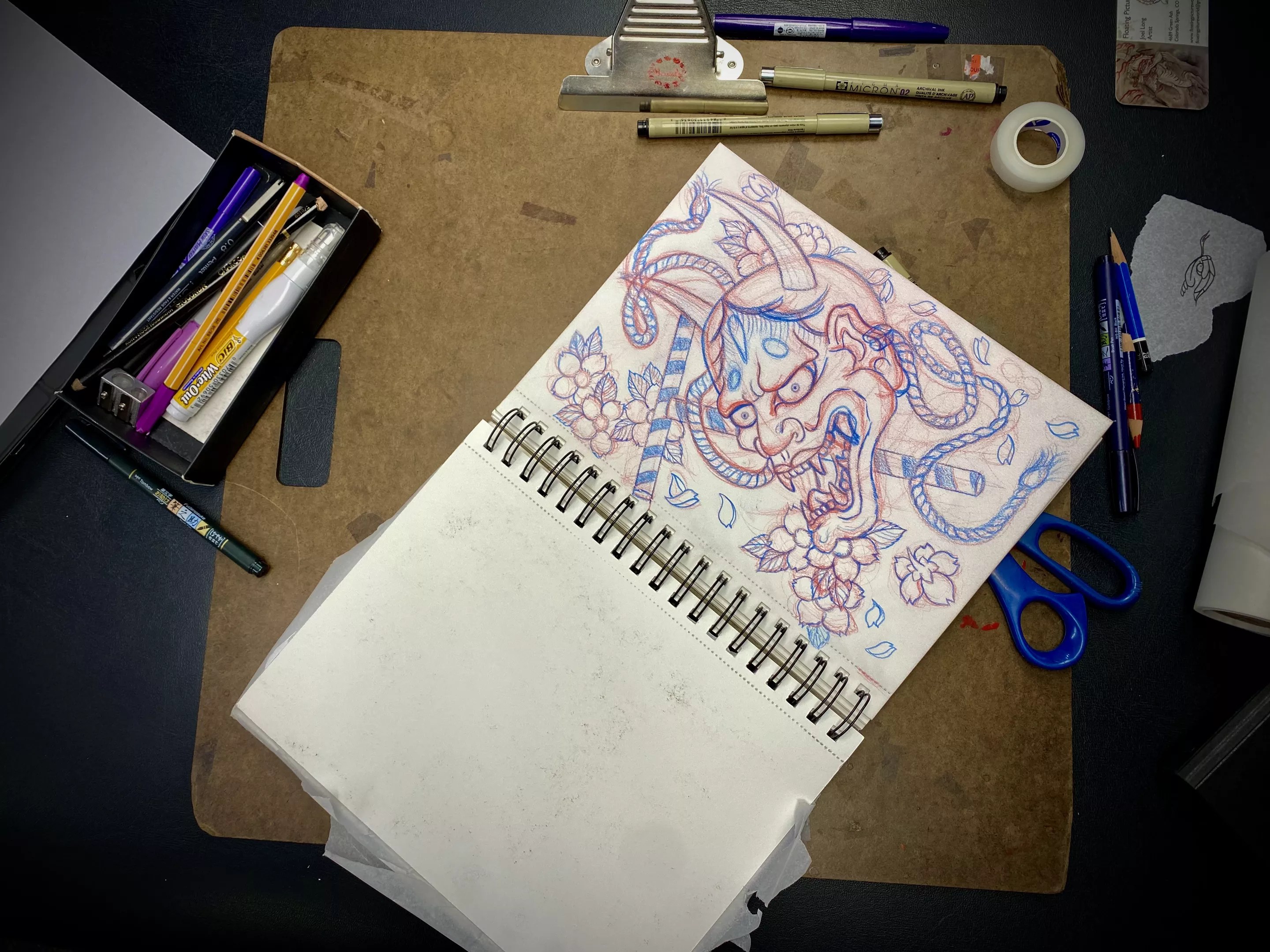

Sketch of a Hannya Mask by Francesco Arlotta

Edward Simpson

Arlotta nods while drawing from the corner, listening to a philosophy that must be familiar by now. “Me and Frank went to Italy and he tattooed his countrymen. I drew a tiger and he tattooed it,” Long divulges. “For my tigers, I’m thinking about what he’s doing. He’s like, ‘What’s up, motherfucker? He’s checking you out – [positioned] in the South. I call that the royal stance,” he remarks.

When pondering his wish for people interested in Japanese tattooing, Long leaves me with a bit of wisdom: “The wind is hissing something important to you. Listen.”