National Ice Core Lab

Audio By Carbonatix

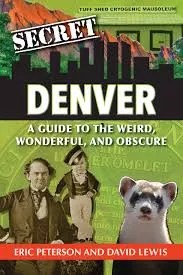

Denver authors David Lewis and Eric Peterson just wrote the book on wild and weird places around the Mile High City. Some are ideal spots to explore during the Halloween season, including Cheesman and Congress parks, which were both built on an old graveyard (as was the Denver Botanic Gardens); the Oxford and Brown Palace hotels are also rumored to be haunted.

But for tales certain to send a shiver down your spine, it’s hard to beat the sagas they dug up connecting Colorado to the Cold War and other chilling eras. “I loved writing about the National Science Foundation Ice Core Facility,” says Peterson. “I wasn’t aware it existed before we started working on the book last year, and was surprised to learn of its critical importance in climate research. To be clear, it’s not obscure in the scientific world…but it was new to me.”

Here are four icy excerpts from Secret Denver: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful, and Obscure.

DENVER’S COLD WAR TIME MACHINE

Ever wished you could travel back to the bad ol’ days of the Cold War?

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has something special going on at its Denver regional headquarters: a journey back in time.

That’s because its Region VIII headquarters is two sites in one. The building acts both as a working office for Rocky Mountain region emergencies and a model Cold War fortress.

The headquarters’ main building was constructed in 1969, when nuclear fear and paranoia ruled the day and guided the FEMA building’s design. That’s why the complex is constructed on two levels; the upper level is under three feet of earth, and the lower one is entirely below ground.

The FEMA headquarters was made mainly of steel, for strength, and concrete, to protect occupants from gamma rays. It was constructed to withstand the worst conceivable nuclear attack, with main and back-up generators, a 5,000-gallon water tank supplemented by an 800-foot-deep well, and air intake designed to filter out radioactive particles.

On the north side of the lobby, steel vault blast doors lead to an underground bunker. At one time, this underground portion of building 710 included male and female dormitories, medical facilities, a kitchen and lunchroom, and, most impressively, a giant coffee urn built right into the plumbing.

Many of these features are gone now, alas, and 710’s bunker consists mostly of windowless offices, albeit with ultra-fancy communications equipment.

Another set of doors leads from the lobby through a long hallway illuminated on either side by lights embedded in the floor, rather like the lights that run along the sides of a jet plane’s corridor. These lead to building 710A, which today is an almost normal-seeming office space-for an underground emergency management agency, that is.

WE ALL SCREAM FOR ICE CORES!

Why is there a massive freezer in a Denver suburb with ice samples from all over the world?

Located just west of Denver at the Federal Center in Lakewood, the National Science Foundation Ice Core Facility (NSF-ICF) has the world’s largest collection of ice cores available to researchers.

Ice cores are cylindrical samples drilled from glaciers and ice fields all over the world. The lab describes them as “frozen time capsules.” Scientists analyze samples from the cores for various research efforts, most of which focus on understanding the past climate states of the Earth.

The NSF-ICF collection includes more than 22,000 meters of ice cores from Antarctica, Greenland, and North America in all. The facility’s primary freezer is big (55,000 cubic feet) and cold: the cores are stored at a temperature of 36 degrees below zero Celsius.

The cores are stored in metallic tubes on shelves in the freezer. When a scientist requests a sample, staffers at the NSF- ICF take it to a slightly warmer (24 degrees below zero Celsius) room to meticulously cut a piece from the core and ship it to the scientist’s lab.

The largest ice core at the facility is from the West Antarctic Ice Shield Divide project, measuring a whopping 3,405 meters in length (more than two miles). Scientists are using it to track changing levels of greenhouse gases and climatic shifts over the past 68,000 years.

This missile silo outside Bennett is for sale.

Loopnet

LOST AND FOUND MISSILE SILOS

What happens when the government decommissions a nuclear weapons facility?

There are eleven former federal missile launch complexes on the plains east of Denver: six Titan I and five Atlas E sites. Both varieties were equipped to fire intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) with atomic payloads halfway around the planet beginning in the early 1960s.

After the facilities were decommissioned in the mid-1960s, the federal government sold them to a variety of public and private owners. One has been converted into a park, others are being used for commercial purposes, and yet others are being converted into private residences.

The missile sites have everything an aspiring supervillain or doomsday prepper would want in a home: plenty of acreage, multiple underground silos, a command center, and a network of connecting tunnels.

However, many of them are also polluted with a variety of nasty chemicals; cleanup and remediation is ongoing.

The pollution hasn’t stopped a few enterprising individuals from taking on these massive fixer-upper projects: one owner in Kansas converted an Atlas E complex into a “subterra castle” with 47-ton blast doors leading into a cozy but impenetrable abode.

As of early 2020, one Titan I complex (near Bennett, about 30 miles east of Denver) was on the market for $4.2 million. The listing highlighted 50,000 square feet of space on 210 acres, with a half-mile of tunnels. The owners were marketing the Cold War relic as a potential hemp farm.

LAMB SPRING’S PREHISTORIC SECRETS

What prehistoric hunting site south of Denver yielded record numbers of mammoth remains?

Lamb Spring isn’t even a spring, its waters having died a natural death in 1970. Today the site appears to be a nondescript patch of rolling prairie a couple of miles east of the foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

Yet the 35-acre Lamb Spring Archaeological Preserve is an important prehistoric site where scientists have found evidence indicating that Paleo-humans lived and hunted in North America more than 8,000 years ago.

In ancient days, the spring was a favorite watering hole for ancient American horses, ground sloths, camels, bison, and Columbian mammoths, great beasts standing about 13 feet high and weighing as much as 11 tons.

That’s why Lamb Spring was a popular place for human hunters, who used spears to kill bison-and possibly other animals-that had gathered to drink.

Lamb Spring’s oldest layer yielded the world’s largest collection of Columbian mammoth remains-perhaps 33 of the great beasts.

Reidy Press

Radiocarbon dating shows mammoth bones at Lamb Spring from a period of about 500 years, some nearly 12,000 years old. It appears those ancient mammoths died of natural causes and might have been scavenged by humans in the neighborhood.

Scientists are doubtful, but some are intrigued by mammoth bones there with what could be butcher marks, along with a great stone that might have been used as an ancient butcher block.

The dig at the site also uncovered a higher layer of Cody Culture-era bison hunters about 8,000 years old, including several stone knives and scrapers.

The excavation since has been filled in, awaiting further funding. All that’s visible now is a metal hut containing reproductions of ancient knives and tools and a copy of a skull of a young female mammoth. The original was discovered at Lamb Spring’s low point, precisely where the hut is located.

Secret Denver: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful, and Obscure, by David Lewis and Eric Peterson, and published by Reidy Press, is available at secretdenverbook.com and Mutiny Information Cafe.