“That overlooks some content or narrative that triggers the journey; it’s more about the kind of materials themselves,” Ward explains. “A lot of the time, my materials are overlooked or seen so much that they’re taken for granted, but there’s something about using them that animates them to tell a story — by using the familiar to bring the viewer into another experiential space.”

Nari Ward, "Amazing Grace," 1993. Baby strollers, fire hose, and audio component, dimensions variable.

Photo by Wes Magyar, courtesy of MCA Denver

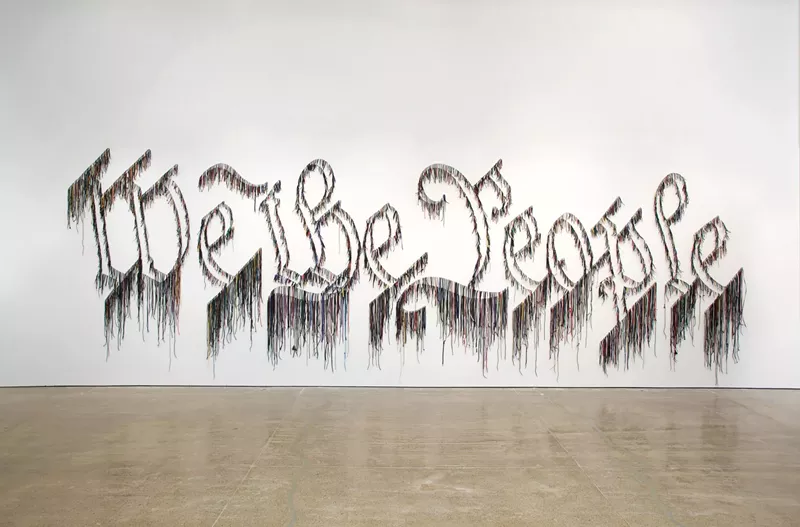

This becomes clear when you eyeball the work. MCA Denver’s new exhibition, Nari Ward: We the People, a survey of the artist’s powerful statement pieces from over the decades, teases both senses and sensibilities from afar and up close, as you realize that the physical works comprise big ideas built piece by piece, grain by grain, out of the salt of the earth.

Nari Ward, “Iron Heavens,” 1995, oven pans, ironed sterilized cotton and burned wooden bats.

Photo by Wes Magyar, courtesy of MCA Denver

Ward, an avid music lover of everything from “reggae to classical to jazz to new age,” also uses sound in various sculptural environments. Walking through “Amazing Grace,” you’ll hear the gospel hymn while looking at a landscape eliciting a sense of waste, overcrowding and life on the other side of the tracks. And 2008's “Glory,” a tanning bed created out of an oil barrel that’s designed to tan the American flag on a body, includes a recording of a parrot singing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Its inclusion was Ward’s chance solution to lighten up a piece that could be darkly misconstrued as a kind of coffin.

Nari Ward, “Glory,” 2004, fluorescent and ultraviolet tubes, computer parts, DVD, parrot audio, plexiglas, fan, camera casing elements, paint cans, cement, towels and rubber roofing membrane.

Photo by Wes Magyar, courtesy of MCA Denver

Harlem, where Ward has lived and worked for decades, is also a wellspring of ideas and activism for the artist. He says that while the nostalgic notion of the Harlem Renaissance has given way to the not-so-beautiful realities of gentrification and economic polarities, Harlem’s densely urban energy also leaves behind plenty of refuse, leaving him to cross one with the other. “You see things you might not see in places where there’s more of a landscape,” he explains. The result of that conflation is visible in his signature transformation of ordinary materials.

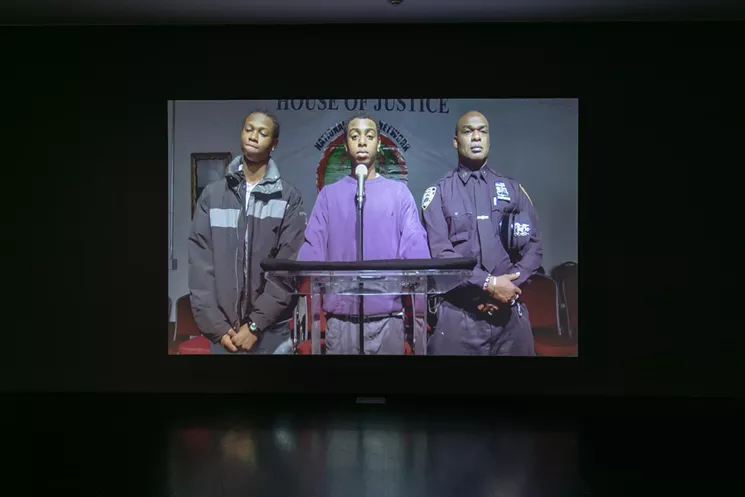

Nari Ward, “Father and Sons,” 2010 (still). Digital video projection, sound, color.

Photo by Wes Magyar, courtesy of MCA Denver

“Thinking about it, I wanted to try and talk about this strange relationship in American history: Policing in the U.S. came out of slave-catching,” Ward says. “White males were hired to capture slaves. There were so many of them, and that was a way to control them. That whole profession came out of that consequence. “But what about black policemen? How do they fit in?” he speculates. “'Father and Sons,' about a black policeman and his two sons, riffs on the irony of the situation, and how we still see the racist consequences of that relationship between policing and the real endangerment black citizens encounter today.

“African-American history is actually American history,” he adds. "It’s time to recognize and call it that. I use these different languages and codes — the symbols that are part of American history — in my works. It’s about bringing that to the forefront, in the moment, as shared experiences.”

Ward doesn't believe that these politicized works should only have power in the museums or galleries where they are displayed. He wants to send a message through his sculptural scenarios that might enlighten viewers and change someone’s mind, no matter where they are. “I use the platform of the gallery and material engagement and try to make something happen outside the museum,” he explains.

Nari Ward: We the People by The Museum of Contemporary Art Denver and Orange Barrel Media from Orange Barrel Media on Vimeo.

Nari Ward: We the People is currently on view at MCA Denver, 1465 Delgany Street, from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Tuesdays through Sundays, through September 20; Mondays from noon to 5 p.m. are reserved for MCA members only. Reservations for timed-entry tickets are required in advance online; find information and upcoming events in conjunction with the exhibition online.Nari Ward’s work will also appear on digital surfaces around downtown Denver along Speer Boulevard, as well as 14th and 16th streets. A new digital work by Ward, titled “LAZARUS Beacon,” based on poet Emma Lazarus's “The New Colossus,” the sonnet on the Statue of Liberty, is included in Night Lights Denver’s free stories-high art projection series on the side of the Clocktower, where it is visible Tuesdays through Sundays; visit the website for information and changing viewing times.