Today, October 20, Butcher's Crossing — the film starring Nicolas Cage that's based on the novel by John Williams — opens at theaters across the country. To mark the occasion, we're republishing this November 2010 piece by Alan Prendergast on the Denver author and educator.

It was 1962 when Joanne Greenberg started getting curious about a writer named John Williams. In those days, what passed for Denver's literary scene could (and often did) fit comfortably in one room — a small band of authors and culture promoters who bumped into each other repeatedly at cocktail parties, lectures, book signings and other events.

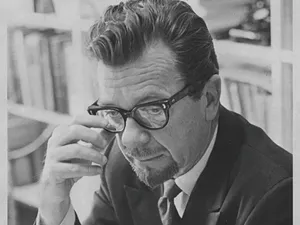

Greenberg was thirty years old. She'd just published her first novel, The King's Persons, and was working on a second, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, which would be a formidable commercial and critical success. Williams was a decade older, an English professor at the University of Denver and a smiling, urbane presence at parties — a drink in one hand, cigarette in the other.

"Williams? He writes Westerns," someone told her.

Greenberg didn't know anybody who wrote Westerns, and Williams didn't look like someone who did. He was short and dapper, with a neat beard and "a face like a five-day rain," she recalls. He invariably wore a white shirt, a blazer, an ascot instead of a tie — and sometimes a red cummerbund. Other than spies and diplomats, who wore a red cummerbund?

Yet that deeply lined face had seen things. After the two appeared on a couple of panels together, it became obvious to Greenberg that John Williams was a serious man — serious about his work and literature in general. When she learned that he had a new novel coming out, she decided to pick up a copy.

The book was Stoner. Sitting in a car in a parking lot, Greenberg opened her purchase with some trepidation. What if it was awful?

It wasn't a Western. It was the story of an obscure university professor, a teacher whose life and career are steeped in disappointment and failure. Greenberg slipped into the first couple of paragraphs — and was quickly in the deep end. "By the fourth sentence, I knew I was in good hands," she says now. "I was just sitting there, getting blown away."

Stoner's colleagues, who held him in no particular esteem when he was alive, speak of him rarely now; to the older ones, his name is a reminder of the end that awaits them all, and to the younger ones it is merely a sound which evokes no sense of the past...

As she was drawn into the oddly compelling work, Greenberg realized that this was how she wanted to write — clear as a mountain creek, without gimmicks or glitz, almost without words. It was the kind of seemingly effortless performance that requires tremendous skill and profound reserves of discipline and love. "He wrote like a Shaker would ski, without a wasted motion," she says. "It was without ego. But that doesn't mean without personality."

The next time she saw Williams, Greenberg raved about Stoner. The book is terrific, she said.

"I think so, too," Williams replied — and then, with typical modesty, began to chat about other things.

Williams published three masterful works of fiction in a twelve-year span, all misleadingly labeled as "historical novels" but vastly different from one another. Each one was greeted with wretched sales and was soon out of print — even though the last one, Augustus, won the National Book Award for fiction, the only work by a Colorado author ever to do so.

People sometimes confuse Williams with the African-American writer John A. Williams, or even with the composer of Star Wars. Yet every few years some astute and influential critic rediscovers Denver's John Williams, with the same shock of recognition Greenberg experienced sitting in her car back in 1965. "Why isn't this book famous?" C.P. Snow asked, writing about Stoner in 1973, after it finally found a publisher in Great Britain.

"John is almost famous for not being famous," Williams compadre Dan Wakefield complained in 1986. "This is Hemingway without bluster, Fitzgerald without fashion, Faulkner stripped of pomp."

Writing in the New York Times in 2007, Morris Dickstein called Stoner "something rarer than a great novel — it is a perfect novel, so well told and beautifully written, so deeply moving, that it takes your breath away." Other Williams enthusiasts have heaped praise on Butcher's Crossing — described as the finest Western ever written and as the first anti-Western — and on Augustus, an astonishing journey through the rise of imperial Rome.

Sixteen years after his death from emphysema at the age of 71, Williams has developed a cult following on college campuses, promulgated in part by generations of his former creative-writing students, now teaching in other MFA programs. And his work seems poised on the brink of much wider recognition. In recent years, all three of his major novels have been reissued in handsome paperbacks. Stoner showed up in Time earlier this year on a short list of "recommended reading" from Tom Hanks. And Focus Features has announced that a movie version of Butcher's Crossing is now in development with director Sam Mendes (American Beauty, Jarhead) and screenwriter Joe Penhall (The Road).

The man behind the work remains an enigma, though. Williams didn't like to talk about himself. People who considered him a dear friend heard scarcely a word about his experiences in World War II, for example, which haunted him for years, or his domestic upheavals (including four marriages). He never whined about the writing "process," loathed questions about where writers get their ideas, and rarely spoke of the sprawling novel about war and fine art he began working on shortly after Augustus, a project that remained unfinished when he died twenty years later.

"He had a private side that he kept plenty private," says Robert Richardson, the acclaimed Thoreau biographer who taught beside Williams at DU for nearly three decades, "without it affecting his friendliness or availability. He did not spend any time feeling sorry for himself, even when he was carrying around an oxygen tank. He was okay with who he was and where he was."

Yet a novelist of Williams's stature doesn't cut a swath through Denver without leaving some trace behind. Unlike Professor Stoner, he made a vivid impact on colleagues, friends and students, who credit him with shaping DU's writing program into one of the finest in the country. They remember a charming, irascible, hard-drinking and driven artist who cared far more about his own exacting standards than public expectations. A meticulous craftsman, he also left a revealing collection of personal correspondence, notes and drafts, all lovingly collected in a university library — although, curiously, not the university where he taught for thirty years.

The memories and papers tell a Williams kind of story — tough and unexpected and utterly without apology.

`"He was a plain guy," says Nancy Williams, his fourth and final wife, who was with him for close to 35 years. "He hated sentimentality or sugarcoating. He looked at writing as a job of work. He used to say that if he hadn't been a writer, he might have been a plumber."

But one hell of a plumber.

Whenever Williams discovered a novel he admired, he would announce that the writer was a "pro" — his most lavish literary laurel. But he had an even higher accolade for someone he found to be sincere and unaffected. Such a person "has no side," he said.

Williams grew up among people who had no side. He was born in 1922 in Clarksville, Texas, and raised in and around Wichita Falls. His grandparents were farmers; his parents knocked about during the Depression, sometimes a step ahead of the rent collector, until George Clinton Williams found a steady job as a janitor at the post office. John was eight or nine before he learned that George was actually his stepfather. He was told that his biological father had been murdered by a hitchhiker while John was still a baby.

By junior high, John had become a voracious reader, was working in a bookstore and dreamed of becoming a writer. A teacher's praise for an essay he wrote on the movie actor Ronald Colman all but sealed the deal. "It was one of the first compliments I ever had in my life about anything I'd done, and I said, 'My God, I've found my vocation,'" he recalled years later.

After high school, Williams enrolled in a junior college in Wichita Falls — and promptly flunked freshman English. He was too restless to study and eager to see the world. He had a deep, honeyed voice, and soon found work as a radio announcer. At nineteen he got married, then promptly joined the Army Air Force.

In 1942 he was shipped to India, where he served as a radio dispatcher on missions that flew over the Himalayas to supply troops deep in the jungles of Burma — "flying the hump," as it was called. After it was over, Williams rarely mentioned the two and a half years he spent in the China-Burma-India theater, other than to note that he used much of his tedious downtime to write and rewrite his first novel, Nothing but the Night, a murky psychological study of a troubled young dandy that he would later emphatically renounce. At some point he received a Dear John letter from the girl he'd married in haste before enlisting.

Decades later, asked by an interviewer if he ever saw combat, Williams acknowledged, "We were shot at occasionally" — then abruptly changed the subject. But his widow insists that the war burrowed into him much deeper than he liked to admit.

Nearly a thousand men and 600 transport planes were lost flying the hump — to enemy fire, deadly weather or treacherous landing strips hacked out of the jungle. Williams flew dozens of missions. He contracted malaria and saw the ravages of famine in India. Once, while lost with a volunteer squad sent to retrieve dog tags from bloated corpses in a downed plane, he was reduced to roasting monkeys on a spit. And while his C-47 wasn't equipped for combat, he later told his wife he was shot down while flying low over the treetops in Burma.

"He always thought it was a Japanese mortar that hit them," Nancy Williams says. "The trees broke their fall. He woke up outside the plane with two or three crushed ribs. The five guys in the back of the plane were killed, and the three in front lived. They had a compass, and they found the Burma Road and walked out.

"John had a bad case of survivor guilt for years after that. When he and I started living together, it was fifteen years after the war and he was still having nightmares. And guilt. And malaria. The war never went away."

Williams never doubted the necessity of the war. "But I finally think World War II brutalized this country," he said in an interview published in 1981. "People almost got used to people being killed."

In 1945 Williams returned to civilian life. He spent some time with his family, who had moved to California, then drifted to Key West, where he helped launch a radio station. He continued to tinker with his novel, sending drafts off to New York editors, who called it an overblown, overwritten short story. Discouraged but stubborn, Williams sent the manuscript to Alan Swallow.

It was a life-changing move. A Wyoming native, Swallow had founded a small press in Denver dedicated to bringing out serious new writers that mainstream publishers neglected. He was also in the process of launching a creative-writing doctorate program at the University of Denver that would be only the second of its kind in the country.

Swallow found Nothing but the Night "rather dreary" and "somewhat overdone" — but not so terrible for a first novel. He told Williams he'd publish it under his own imprint, even though he would certainly lose money on the deal. "You may well be a writer who needs to throw away two or three novels before the thing starts clicking," he wrote to the jubilant author.

The book was published in 1948 and disappeared quickly. Swallow agreed to publish a volume of Williams's poetry, too. More important, he persuaded Williams to come to Denver and resume his education at DU. Williams got his bachelor's degree there in 1949 and his master's the following year, working with Swallow in the classroom and doing various chores at the press, including setting type. A second marriage came and went; he'd married "too soon" after the Army, he later said.

Williams took his doctorate at the University of Missouri. His dissertation, on the Elizabethan poet and dramatist Fulke Greville, fared better than a second novel he wrote during that period about American bohemians in Mexico, which was rejected by 22 publishers. "Just too long and too pretentious," one editor wrote.

Dr. Williams collected his degree in 1954 and headed back to Colorado, to accept the only teaching job he'd been offered. Swallow had stepped down at DU in order to pursue his publishing business, and Williams succeeded him as director of the university's budding writing program.

At the time, DU was a small, isolated, distinctly under-endowed institution, an obscure backwater in the currents of academe. Williams had a staggering load of undergraduate and graduate courses — and a third marriage, one that survived into the 1960s and produced three children — and little time for his own writing. Still, he was determined, like Swallow, to take the supposed obstacles of working far from the publishing establishment back East and turn them to his advantage.

Shortly after his return to Denver, he began reading widely in the literature of the West. What he found was a lot of cheap myth-making and silly shoot-em-ups and little that seemed to address how people actually lived and struggled in that narrow window of time we now associate with the Wild West. Even highbrow authors tended to romanticize the region. "The subject of the West has undergone a process of mindless stereotyping," Williams wrote in a personal manifesto in The Nation, "by a line of literary racketeers...men contemptuous of the stories they have to tell, of the people who animate them and of the settings upon which they are played."

Williams began to ponder how best to convey the authentic experience of the frontier, the harsh elements and terrifying vastness of the place. The story that emerged from these musings concerns one Will Andrews, a young man who drops out of Harvard in the 1870s and heads west, brimming with Emersonian ideas about Nature and eager for an adventure that will unlock "the Wildness" in himself. Shortly after his arrival in the desolate Kansas town of Butcher's Crossing, he decides to bankroll what promises to be one of the last great buffalo hunts, at a time when the animal had been all but annihilated by the hide trade. Miller, a seasoned hunter, leads the expedition to a herd of thousands in an isolated valley in the Colorado Territory. But Miller becomes obsessed with killing every last buffalo; the men are trapped by the sudden onset of winter in the Rockies, and Andrews soon learns more about Nature's indifference than he ever cared to know.

Butcher's Crossing is a quantum leap from Williams's turgid early work, in language as well as subject. Every aspect of Andrews's ordeal, from the tedium and agony of riding horseback for days across empty prairie to the mindless killing and skinning of thousands of buffalo to the struggle to survive for months in the high country, is presented in vivid, stunning detail. Yet the prose is austere and almost unbearably dispassionate, the tale told crisply and clear-eyed even as it descends into brute slaughter:

Miller shot, and reloaded, and shot, and loaded again. The acrid haze of gunsmoke thickened around them; Andrews coughed and breathed heavily and put his face near the ground where the smoke was thinner. When he lifted his head he could see the ground in front of him littered with the mounded corpses of buffalo, and the remaining herd — apparently little diminished — circling almost mechanically now, in a kind of dumb rhythm, as if impelled by the regular explosions of Miller's guns.

Williams's agent entered the manuscript in a national fiction contest sponsored by Macmillan. It won second prize, earning the author $2,500 and a book contract. Published in 1960, Butcher's Crossing sold fewer than 5,000 copies in hardcover. No one knew how to market it; the New York Times assigned it to a reviewer of pulp Westerns, which incensed Williams. A paperback house wanted to reissue it, but only if the label "A Western" appeared on the cover. Williams refused.

Along with Oakley Hall's Warlock, Butcher's Crossing was one of the first serious novels about the West. Within a few years, the groundbreaking work would have plenty of company, as writers such as Cormac McCarthy and Larry McMurtry and filmmakers such as Sam Peckinpah and Robert Altman began to reinvent the Western myth or peel it back to see what lurked beneath. But in Denver, Williams became known as a writer of "Westerns" — even though his story of ideals crashing on the killing floor of experience is about much more than a buffalo hunt, just as Moby-Dick is about much more than a whale hunt.

After his death, Williams's widow opened the book for the first time in years and looked again at the remarkable section dealing with the slaughter of the herd, which goes on for forty pages.

"It struck me that the intensity of that passage comes from his own experience in World War II," Nancy Williams says. "He had seen so much death, so much senseless killing."

In the 1960s, DU's English department doubled in size, then doubled again. The growth was triggered by a surge in freshman composition classes, previously handled by a communications department, but it also signaled an explosion of baby boomers and older graduate students hitting college campuses, the soaring population of the region, and an increasing interest in advanced creative-writing programs.

When Gerald Chapman arrived as the new chair in the early 1960s, he became the eighth member of the department; there had been just four in 1959. By the time Chapman stepped down as chair eight years later, the full-time faculty had swelled to 28. "We had something very special going," Chapman says now, "an esprit de corps I've never seen anywhere else. John was part of making that happen."

In addition to teaching prosody, the modern novel and other English courses, Williams had built the writing program into one of the most academically demanding in the country, reasoning that most writers would have to find teaching jobs in order to support themselves. A doctoral candidate in creative writing was required to take the same load of courses as Ph.D. candidates in English literature, while producing a dissertation that might be a novel or a book of poetry.

"He'd say, 'It never did a writer any harm to be educated,'" recalls novelist David Milofsky, who taught at DU in the 1980s and is now at Colorado State University. "I wish more people felt the same way."

"It was one of the few departments in the country where the writers weren't at war with the academics all the time," says Bob Richardson, who arrived shortly after Chapman and stayed 27 years. "They tried to get writers who were open to the possibility that people who are scholars might also be smart, and scholars who respected writers. Because of John and his evenhandedness, it worked. It became certainly the most exciting and fulfilling department I've ever taught in."

The English profs were a tight-knit group, given to considerable socializing and parties. And alcohol was an essential lubricant of the gatherings, particularly if Williams was involved. When he first applied for a job at DU, Richardson was flown out for a "campus" interview that actually took place miles away. "The main part of the interview was being taken up to the mountains to a small cabin and made to drink too much," he recalls. "That way they very quickly found out who you are underneath. They weren't interested in prestige degrees. That's the great thing about Denver: What matters isn't where you're from, but whether you can do the job."

The camaraderie extended to graduate students, too, some of whom were as old or older than the youthful faculty. After lecturing in a fog of cigarette smoke through his allotted class time, Williams would adjourn to the Campus Inn with a gaggle of students in tow.

"John would buy the first pitcher, and then you'd talk literature for two or three hours," says Bill Zaranka, who arrived as a doctoral student in 1969, later headed the creative-writing program and is now provost emeritus at DU. "I remember being invited on numerous occasions to his house. He didn't hold forth; he'd talk about everything but his own work. But you never doubted where he stood."

Williams had high standards for his students. Some of his charges found him too brusque, too dismissive of writing that he didn't believe made the mark. He could be disorganized in his approach to paperwork and utterly disinterested in "fashionable" trends in literature or criticism. But others found him to be a generous friend and good listener, a brilliant and incisive critic — and a decided departure from a stereotypical professor.

"He came up the hard way," says Phil Doe, who studied with Williams starting in 1968 and became a lifelong friend, often joining him to work the sprawling garden behind the professor's house on South Madison Street. "He was a grand admirer of Willa Cather and people who weren't in the mainstream, people from humble beginnings with great literary skill. He thought education was a pretty private business. He'd open the door for you, and the rest was up to you. Some people accused him of being lazy about teaching and being more interested in his writing, but I didn't see that in his classes."

A Williams writing workshop wasn't the sort of group therapy one finds in MFA programs these days — but it wasn't a ritual of humiliation, either. "He would criticize a story as being 'the great unwritten story' that was still in the writer's head — he didn't get it out on the page," says Joe Nigg, who went to DU in the 1970s and has since authored several books on mythical beasts. "He wasn't mean at all. It had nothing to do with the personality of the writer."

"He would talk for an hour and meticulously dissect a story in the nicest possible way," adds Milofsky. "Nobody else would speak. When he would finish, he would say, 'Now, is there anything else wrong with this?' And there was nothing more to say. It was amazing."

Joanne Greenberg had such respect for Williams that she asked him to critique some of her work in progress — a rare leap of trust for an established author, and one she never regretted. "He was the consummate teacher," she says. "Ego and self-consciousness had no place. When you got his critiques, it was always about the work, and the work was important. I never came away from a session with him without being on a high."

Williams never coddled students, but he did take extra pains with those who he thought showed promise. Michelle Latiolais, now a published novelist and English professor at the University of California at Irvine, remembers her astonishment, back in her DU graduate days, when Williams descended on her after class with a stack of books and told her, "Ignore all of what you just heard. Read these authors."

"I had just withstood a very ugly workshop that he felt was off the mark," she says. "I was attempting a type of prose that John felt very strongly couldn't be taught, but he knew I would find all the tools I needed in the great writers."

Latiolais acknowledges that some students felt intimidated by Williams. Others were comfortable dropping in on him in his office, squeezing their way in among blizzards of paper and scattered books and knocking back a shot of Wild Turkey from the bottle Williams kept in his desk for rarefied conversations. But what he tried to impress on all his students, she says, was the high-stakes nature of their work: "John would point out the window at the 'real' world and say, 'Out there, that's an amateur performance.' The truth was on the page, through craft and artifice. He was very exacting, but he was never vicious, ever. It was just really serious, what we were doing."

Even as his real-world obligations multiplied, Williams was hard at work at his own high-stakes pursuit — a novel about the darker implications of a life devoted to study and teaching. It's the story of a farm boy, sent by his family to the University of Missouri to study agriculture, forty years before Williams arrived there; instead, he falls madly in love with literature.

William Stoner is a clumsy but earnest student. He marries badly, resulting in one of the bleakest honeymoons in fiction. He's an indifferent scholar, and it takes him years to figure out how to light a spark in the minds of his own benighted pupils. He has a doomed daughter, a doomed love affair with a graduate student, and a long-running feud with a colleague that cripples his career. The sacrifices he makes to hold on to what he loves most are horrific and ultimately futile. Yet in the end, Williams once noted, he has "more than most of us ever gain — his own identity."

He suspected that he was beginning, ten years late, to discover who he was; and the figure he saw was both more and less than he had once imagined it to be. He felt himself at last beginning to be a teacher, which was simply a man to whom his book is true, to whom is given a dignity of art that has little to do with his foolishness or weakness or inadequacy as a man.

Williams wrote the story longhand over a period of years, working from detailed notes and outlines. There are few revisions in what appears to be the original draft — an amazing feat for a book so careful in its language. Despite what sounds like dry and unpromising material, the novel is by turns engrossing, infuriating, painful and poignant. In one chapter, Williams wrings more genuine drama and suspense from an unscrupulous graduate student's oral exam than can be found in a stack of James Patterson potboilers.

It's tempting to see echoes of the author's personal turmoil in Stoner's disastrous journey. Williams's third marriage was falling apart as he wrote it; until he finally divorced, he spent part of each week with his family and part with Nancy, a teacher and former grad student with children of her own. But such a crude biographical interpretation diminishes the living, breathing character Williams created, a deeply flawed man the reader comes to know intimately and mourn. Stoner is "one of the few characters who really die in fiction," Harry Crews once wrote, a testament to the power of his creator's achievement.

It would be hard to conceive of a project more out of tune with the primal scream of the 1960s — the Age of Aquarius, Vietnam, psychedelia, James Bond, Mailer and Capote. Stoner was turned down by seven publishers. After the seventh rejection, Williams told Nancy, "Well, I don't have to write novels."

"That scared me to death," she says. "I knew how tough he was and that he meant it."

On the eighth try, a young editor named Corlies Smith, who'd discovered neglected talents ranging from Jimmy Breslin to Thomas Pynchon, managed to persuade the higher-ups at Viking to take a chance on Stoner.

The book sold abysmally. But like its protagonist's life, it would in time prove to be a singular triumph, wrapped in the trappings of failure.

After Stoner, Williams found himself increasingly in demand as a visiting professor or a speaker at conferences. He was encouraged to apply for and received prestigious grants and awards. He didn't have many readers, but they were the right ones — the high princes and satraps of academia and the publishing industry.

A year after the novel's inauspicious debut, grand punjab Irving Howe tossed Stoner a belated bouquet in the pages of the New Republic, generating a flurry of new interest in the already out-of-print work. A cult began to develop among teaching assistants, who thrust scarce copies of the book on one another as if it held the key to their vocation. At DU, the library's copy developed a crack down the spine, as waves of grad students prepped for orals by pondering the central clash between Stoner (a classicist) and his intellectual nemesis (a romantic).

One of the book's fans was poet and Dante translator John Ciardi, who presided over the oldest and most hallowed writing workshop in the country: the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference in Vermont. Ciardi invited Williams to join the staff of the two-week gathering, and he became a regular for the next seven summers, until Ciardi's departure in 1972. For Williams, it was an intense and exhilarating escape from routine, a chance to connect with the literary world well beyond Denver. He formed close ties with many of the "pros" he met, including Ciardi, Dan Wakefield, Isaac Asimov, Diane Wakoski, Harry Crews and poet Miller Williams. In many cases, he persuaded them to come to DU to lecture.

"He was able to talk about writing fiction in a way that helped people learning to write better than anybody I knew," recalls Miller Williams. "A lot of writers talk about it, but you can't use anything they tell you."

In the Ciardi years, Bread Loaf was also a floating bar of literary bad boys. Bloody Marys were served before lunch, with the real drinking starting in the afternoon and continuing well into the night. Nancy thought the whole affair sounded entirely too wild and only joined her husband in Vermont once.

"I hadn't planned to go," she says. "I had young kids, and it was hard to get away. But his buddies called and said, 'Nancy, please come. John is so lonely, and he won't sleep with anybody else.'"

"It was a feast of vanity," says novelist Seymour Epstein, who met Williams in 1966, when they were both at Bread Loaf for the first time. "A lot of drinking and a lot of talking."

Both World War II vets, Epstein and Williams hit it off from the start. Williams invited Epstein, who'd published the well-received novel Leah in 1964 but had no college degree, to teach for a year at DU; he ended up joining the faculty and staying for twenty years. Sy and his wife, Miriam, became close to John and Nancy, and every summer, the two men would drive together from Denver to Vermont for Bread Loaf.

"It was quite an experience," Epstein says of those trips. "John wasn't an easy conversationalist. I would do most of the talking. Around three or four in the afternoon, it was as though a light had gone on. John was beginning to feel the need for a drink, and there was a change of personality. He would become even more reserved."

Drinking, Epstein notes, brought his friend out of his shell. But then it would go on too long: "He used to come to our house and stay until one, two, three in the morning. Both of us were bug-eyed listening to him."

Yet there were peculiar gaps in the conversation. Williams never talked about the war with Epstein. And he was not given to shop talk, not only about his own work but about that of other writers.

"He thought it was outré, amateur to talk about your writing," says Epstein, now 92 and still writing. "He never would have offered me the job if he hadn't read my work. But I don't remember him ever saying a word about my writing."

Epstein knew that his friend had invited him to join the program at DU in part to give himself more time for his own writing. But Williams scarcely talked about the work in progress, a novel as radically different from his earlier books as Stoner was from Butcher's Crossing. It was about a key moment in ancient history that had been explored by everyone from Shakespeare to MGM — the assassination of Julius Caesar and the rise of his nephew Octavius to power amid intrigues involving Cleopatra, Brutus, Cicero, Mark Antony and others.

Williams wasn't interested in writing a Cecil B. DeMille epic or imitating Robert Graves. He particularly wanted to avoid doing a "modern" interpretation of ancient Rome. ("Determined not have Henry Kissinger in a toga," reads one note.) But he was intrigued by the challenge of working from the fragmentary historical record in order to construct an imaginary but plausible account of how Octavius became the emperor Augustus while sacrificing friendship, youthful ideals — even his own daughter, whom he exiled for adultery.

Largely on Irving Howe's recommendation, Williams obtained a Rockefeller grant that allowed him to visit Italy and scout the locations where it all happened. He also spent long hours scouring ancient texts in translation.

He wrote slowly and with great care, as always, working in an upstairs home office, writing longhand or typing on a Remington manual. "He'd start at eight, take his coffee up and write for maybe three hours," Nancy Williams says. "For him, a page was a good day. Two or three pages was a triumph. It didn't happen very often. Then he'd come down, have some lunch. Then he'd go upstairs and plan the next day's work for two or three hours."

The book emerged as a series of letters and journal entries from courtiers and spies, from Cicero and Marc Antony and the emperor's daughter Julia, and finally from Octavius Caesar himself. The mélange of numerous characters and voices became a stunning, polyphonous meditation on the elusiveness of power and the impermanence of empire. It's not Kissinger in a toga; in its tragic sweep, it's more like The Godfather in 3-D, but with one saving grace. Empires don't last, we learn, but the stories about them do.

With Augustus, Williams breathed new life into the epistolary novel and finally seized the attention of the literary establishment — or part of it, anyway. In 1973 the novel won the National Book Award, but Williams had to split the thousand-dollar prize with a co-winner, John Barth's Chimera. Some have argued that the award was an attempt to make amends for ignoring Stoner seven years earlier, but the tie also indicates the emerging schism in the book world between the experimental and the traditional, old forms and new.

Williams accepted the honor with grace and professed not to care if he had a thousand readers or a hundred thousand. He never expected to get rich off his work and treated every royalty check, no matter how modest, as an unexpected gift that must be spent immediately. He knew that his own versatility made it impossible for him to be what Greenberg calls a "dependable writer" — someone who, like Stephen King, delivers a reliable product for readers who just want more of the same — and thus he would never be a brand-name author.

Yet even the award failed to do much for sales of Augustus, and some friends detected a simmering resentment in Williams over the publishing business. "I thought he was one damn fine writer," Epstein says. "He treated the turndowns with contempt, and he should have. There wasn't a reason in the world why his books should have been rejected. You wonder how he could contain himself.

"But that's one of the interesting things about his drinking. All that rage was stored up, and it came out when he started his nightly booze — directed at the wrong targets. He could get very aggressive."

Williams's dependence on alcohol had gone largely unremarked amid free-wheeling faculty parties or in the boozy summers of Bread Loaf. ("Hope you are unlicensed, licentious, profligate, drunken, bloated, and happy, even though it be to your moral damnation," Ciardi wrote to him in 1971. "And more of the same to that damn metabolism of yours that need forego nothing.") But the effects became more pronounced as he got older, as did his chain-smoking. The drinking put a strain on his relationship with the Epsteins, and others as well.

"It hurt me badly," Greenberg says. "I told him, 'John, if I had your talent, I would take such good care of myself.' But he was great at waving things off."

"He could be a mean drunk verbally," Nancy says. "He could say some nasty things. He'd drink a little every day, too much on Saturday. Then he went to work and didn't work."

In the late 1970s, Williams was diagnosed with emphysema. He started showing up on campus tethered to an oxygen tank, but he refused to let it interfere with his long-established classroom routine. He'd take a puff of a cigarette, then a puff of oxygen, then resume his lecture.

Williams's last years at DU were marked by health troubles and rising grumpiness — about the state of education, the ugly new glass buildings downtown, the way Denver was starting to look as "fakey" as every other place. His doctors nagged him to move to a lower altitude, where he could breathe better.

Creative-writing programs were exploding on campuses across the country. DU, still clinging to what Zaranka describes as a "conservative aesthetic," was struggling to catch up. Williams no longer directed the writing program, but some rifts with colleagues had developed over the years that probably made the place feel less like home than it once was.

"I loved John, but there were people there who didn't feel the same way," says Milofsky. "Some people felt John was acting like a big-shot writer. The fact is, he was a big-shot writer. It's remarkable that more fuss isn't made over him."

Williams retired in 1985. He and Nancy moved to Key West, home to literary friends such as Richard Wilbur and James Merrill, but found the hospital services too limited for their needs. They relocated to Fayetteville, Arkansas, where several former Bread Loaf companions taught at the state university.

Shortly after his departure, Robert Pawlowski, who succeeded Williams as director of the writing program, nominated him for an honorary degree from DU. "They wouldn't have anything to do with it," Pawlowski says. "There was some feeling against John among certain people in the upper administration, some petty issues, I guess. But he was the most distinguished person in that department."

A fuss was made, finally, on March 29, 1986, with a series of readings and panels at DU and the Denver Public Library focusing on Williams's work. The guest of honor drove out from Fayetteville and basked in the appreciation and opportunity to see old friends — in some cases, for the last time. A special issue of the Denver Quarterly, the literary journal that Williams had founded twenty years earlier, was devoted entirely to essays, interviews and his work.

The highlight of the issue was a long excerpt from The Sleep of Reason, a novel about war and art forgery that Williams had started after Augustus. In some respects, the new work suggested his most ambitious design to date. Although many of its scenes are set in Washington in the Watergate era, "the novel ranges in time and place from the Quattrocento to the Napoleonic invasion of Italy, and from the Berlin of the Thirties to World War II in both Italy and Burma," he noted in a grant application.

The book had its origins in a trip Williams took to Portugal with Nancy in 1976, during which he began a thinly fictional account of his own wartime misadventure of getting lost in the jungle with a small team. He abandoned the sketch after fifty pages, though. "It was too close to his own experience," Nancy says. "He said he bored himself."

Williams found a more promising approach in an article in Esquire, a memoir by an art curator who'd been captured and tortured by the Japanese and spent the next twenty years trying to come to terms with the ordeal. Williams saw the potential of the story to become an exploration of identity, the consolations of art and the aftershocks of war — what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder.

By 1980 he'd written a hundred pages, including some riveting scenes of the hero's capture by the Japanese. Then he went into the hospital for removal of part of a lung that turned out not to be cancerous at all. It took him months to recover from the operation. There's no indication that he ever wrote any more of The Sleep of Reason, or any other fiction, in the last decade of his life.

"He always hoped to get back to it, but cigarettes and alcohol took their toll," Nancy says. "I think that's the main reason we don't have that wonderful book."

After the move to Fayetteville, the University of Arkansas Press reissued all of his published fiction, and the university library acquired his manuscripts and papers. Williams taught one writing course there as a favor to friends but found it almost beyond his strength; at one point he asked Greenberg to take over for a week.

"What did I find? So much love from those students," Greenberg recalls. "They were from all over the country, and I asked them what they were doing in Fayetteville, and they said, 'John.'"

He stayed at home, mostly, receiving friends and watching with great interest the squirrels and birds vying for the feeder outside his office window. Every week he'd get tidied up for the arrival of the cleaning lady, a middle-aged country woman with no side that he could visit with for hours.

There was another trip to the hospital and nurses and hospice care. "He never expected to live as long as he did," Nancy says. "We said goodbye a hundred times. He'd be lying there, and it was so hard to breathe. He'd say it was almost not worth it. But I would hear that word 'almost.'"

He died of respiratory failure on March 3, 1994.

Years earlier, he had considered using a line from Ortega y Gassett as an epigraph for Stoner: "A hero is one who wants to be himself." He understood too well that people set out to change the world and were instead changed by it — and sometimes crushed by it. Yet those who, like Stoner, pursued their work as a holy calling had the best chance, not of surviving — who does? — but of becoming themselves.

For John Williams, that was all that mattered.