Evan Sem

Audio By Carbonatix

History can be written on the walls of a city, and in 2020, Denver’s walls haven’t stayed blank for long.

Artist Austin Zucchini-Fowler graced boarded-up buildings with paintings of heroic nurses and other first responders, while Koko Bayer wheat-pasted the word “Hope” inside a heart to comfort a city in crisis. Businesses offered up walls where Thomas “Detour” Evans created massive portraits of Isabella Thallas, Sandra Bland, George Floyd and Elijah McClain.

But at the same time that the Spray Their Name crew was commemorating victims of racist law enforcement and other violent acts, Black Lives Matter murals by Karlee Mariel and Armina Jusufagic, newcomers to the scene, were scribbled over with anti-Marxist scrawls, and the artists had a Slurpee hurled at them while they were painting an image of two masked women kissing. Anti-racists have modified white-supremacist graffiti, and in turn, white supremacists have modified anti-racist graffiti. Days after Denver cops unloaded less-lethal weapons into crowds of demonstrators, the city commissioned artists to paint the words “Black Lives Matter” on Broadway. With money from Denver Parks and Recreation, the Black Love Mural Festival hired artists to paint plywood protecting historic sculptures in Civic Center Park, just after protesters had vandalized and knocked over monuments to Christopher Columbus and the Civil War.

During the pandemic, street-art festivals have multiplied as cities and organizations realized that they’re one of the few cultural activities where social distancing comes easy – and that can also have economic benefits.

Currently, Crush Walls is back for its eleventh year, this time both online and in the RiNo Art District and an ever-expanding circle of neighborhoods around it. Over the summer, the Black Actors Guild organized the first Colfax Canvas Mural Fest in Aurora. Last month, Babe Walls, an event highlighting women and non-binary artists, brought murals to low-income housing projects in Westminster. At the end of August, Colorcon returned to the Golden Triangle for its sophomore edition, and this past weekend, Street Wise Boulder, an artivist fest, wrapped up its second year of wrapping Boulder businesses in political paintings.

Rural Colorado has also jumped on the trend, with the Fraser Mountain Mural Festival up in the Rockies and the Some Girls and a Mural collective painting murals on grain elevators and wind turbine propellers on the eastern plains.

No matter the mark or the message, right now someone in Colorado is contemplating the writing on the wall – plotting to scribble over it, exploit it for a new real estate project…or simply celebrate it.

Thomas “Detour” Evans and Hiero Veiga’s portrait of George Floyd.

Kyle Harris

While it’s tempting to view all this creative activity as something new, the history of street art in the Mile High City stretches back at least half a century, to a group of artists involved in the Chicano civil-rights movement.

In 1968, nineteen-year-old Emanuel Martinez stuck out his thumb and hitchhiked from Denver to Mexico City. The young activist, who’d worked alongside Corky Gonzales since age fifteen and had been involved with the Crusade for Justice from the beginning, also dabbled in muralism, and was on the hunt for muralists to train him.

Over the previous three decades, muralism had largely dried up across the country, after Franklin Delano Roosevelt had put 10,000-plus artists to work nationwide through the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal project during the Great Depression. The sweeping paintings commissioned by the WPA for government buildings across the country were in part inspired by Mexico’s government-funded mural movement of the 1920s, which helped that country form its national identity after the Mexican Revolution.

Led by Los Tres Grandes – David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera – the movement turned public spaces into permanent art installations honoring the agricultural and spiritual legacy of both Hispanic and indigenous cultures. The artists used paint to write the nation’s history. Their works were aesthetically bold, grounded in the past yet fiercely modernist. They conveyed the sweeping emotions of a new country with ancient roots and defined what muralism would be for the next century.

“I was very inspired by the Mexican muralists and wanted to do what they did, which was educate people about their culture and instill pride in who they were,” Martinez recalls. While Rivera and Orozco had been dead for years, Siqueiros was still living, and the young Denver artist succeeded in finding the master muralist and then studying with him.

Armed with newfound knowledge, a revolutionary spirit and a deep commitment to his indigenous heritage, Martinez returned to Denver to begin his career. But there was a problem: He had to help build a mural scene from scratch.

Denver in the 1960s was not the street-art mecca it has become over the past twenty years. There was little institutional support for public art, and any wall art you might spot around town was most likely a commercial message or advertisement painted decades before.

Martinez had his own message. In the same way that the Mexican muralists had created a sense of Mexican cultural pride, he wanted to instill an appreciation of Chicano culture in Denver. To do so, he longed to paint monumental murals, public art that would assert the presence of his community in the history of the region, that would inspire people to embrace their heritage and spiritual traditions, and that would remind the city permanently of long-forgotten myths, stories and people. Through large-scale works on public buildings, he wanted to create art that would be as unmovable as the sculptures of genocidal explorers like Christopher Columbus that littered parks across town. His was a quest that demanded massive walls. Instead of being confined to galleries and museums that mostly ignored Chicano artists at the time, he wanted his work to be loud, irrefutable proof that his community was resisting colonialism and was here to stay.

“I was very inspired by the Mexican muralists and wanted to do what they did.”

In 1969, Martinez fantasized about painting a mural at La Alma-Lincoln Park. Chicanos mostly used the grounds of this spot just south of Colfax in west-central Denver, but whites dominated the pool. He and his friends set out to change that.

“We decided the pool should be community-controlled,” he recalls. “At that time, it was just Anglos who managed the pool and the lifeguards. Three of us guys left the Crusade and moved into the housing projects. Our goal was to take over the swimming pool, which we did.”

Part of their plan involved creating a mural that would assert the Chicano community’s right to use the park. But securing a place from the city to paint in those days wasn’t easy.

“They wouldn’t let me paint anything on the wall unless I was an employee, so I became a lifeguard,” Martinez says. “I went through the safety testing and all that.”

He painted his first mural on a garage in Lincoln Park that housed lawnmowers and trucks.

“The agreement I had with Parks is they allowed me to do the murals, but they weren’t going to finance them in any way,” he says. “I had to get my own paint.”

A nearby paint-supply store that was trying to dump recently outlawed lead paint donated everything he needed. He drew the composition on the wall and recruited kids from the neighborhood to do the painting. This collaboration made it a true community mural – a tradition that Martinez says he fears no longer exists. (The practice has not been totally obliterated: This summer’s massive Black Lives Matter street mural on Broadway by Adri Norris and street-art entrepreneur Pat Milbery involved hundreds of volunteers.)

Detail of “La Alma,” by Emanuel Martinez, La Alma Recreation Center, 1325 West 11th Avenue.

Evan Sem

After that first project, Martinez began to paint other buildings in the park. He started leading workshops with kids and was appointed the head of La Alma Recreation Center – a position he only took because it allowed him to continue making art on the walls and teaching the art form to youth. Eventually, Denver Parks and Recreation head Joe Ciancio, a pillar of the Italian-American community, agreed to hire Martinez full-time as a muralist if he would help lure Chicanos into voting for the re-election of Mayor William H. McNichols Jr.

“I wasn’t into McNichols,” admits Martinez. “I wasn’t really into the Democratic Party or anything. I agreed and said, ‘Sure, I’ll do what I have to do. I just want to paint murals in the community.'”

Martinez prides himself on being the first and last official muralist of the City of Denver.

In 1970, he recruited Roberto Lucero to lead a mural-painting project at Columbus Park on the north side of town, where the population was changing from largely Italian to primarily Chicano. Lucero designed a piece featuring the Aztec Sun Stone and the leader Cuauhtémoc.

After the mural went up, Ciancio and then-City Councilman Eugene Dimanna, a prominent Italian tavern owner, balked. “They called me in the office and told me, ‘We don’t like what was done, and we want you to paint over it, because you’re our city muralist,'” Martinez says, noting that since the park was called Columbus Park, they wanted an image with Columbus in it. “That would be the last guy I’d put in there. That would be the absolute wrong thing to do. I wasn’t going to paint over my friend’s mural.”

So the city fired him.

“I lost my job. So what?” he says. “That kind of ended my era of working with the city except as a muralist.”

Martinez and other muralists involved in the civil-rights movement of the ’60s, including Carlota EspinoZa and Leo Tanguma, continued to paint the walls of Denver through the ’70s and ’80s, asserting Chicano culture as a defining part of the city’s history. Their work received international attention, and in 1978, filmmakers producing a documentary about the murals of Denver made Martinez a central part of the film.

“They wanted to do a mural that could be shown on the film in one or two minutes,” he says. “La Alma approached the filmmakers and asked if I could do a new mural on the new rec center there. I agreed to do that. I didn’t get paid for it. I wasn’t on real good terms with Parks and Rec at the time. I told them, I’ll do it. I got the community involved. They filmed it from the very beginning to the very end, with these short shots they condensed into a minute or two. That was the birth of the ‘La Alma’ mural.”

The iconic mural, rich with symbolism, pays homage to the spirit of Denver’s west side and the communities that intersect there.

“The sun radiates behind the silhouetted city, while an eagle embraces two female faces, one representing the moon and the other, earth,” Martinez writes in his artist statement. “A contemporary figure portrays the strength of our youth, on his shirt, the Mestizo symbolizes the mixture of Spanish, Indian and Mexican descent. The ancient indigenous figure holds two vessels bearing a constantly burning flame conveying the vitality of cultural energy. Clutched in the claws of the eagle, a human fetus and skull, symbolizing both life and death. Perched on the braid of the female figures, an outstretched butterfly represents rebirth. Emerging below, an ear of maize signifies fertility and prosperity.”

Community members helped Martinez paint “La Alma,” and over the years, they have protected it. In the early ’90s, after teenagers from the nearby housing project tagged the mural, activists asked Martinez for alternatives to turning them in to the police. The artist submitted a proposal to the city to restore the painting. He received a grant, and the kids who’d tagged “La Alma” helped him repaint it, bringing new meaning to the term “restorative justice.”

“It was front page of the Rocky Mountain News, how I got these taggers to paint the mural,” he says. “They were really excited about it. They loved it. … I had other people help, too, not just them. It became a real community mural that the community protected.”

Mural by Emanuel Martinez at Kachina.

Danielle Lirette

Over the years, Martinez has consistently demanded that the city do more to support artists of color. His advocacy for equity in arts funding, as he tells it, has not won him many friends.

Since the city started funding public art through the one-percent-for-art program created during Federico Peña’s administration, Martinez says that Denver has only commissioned him to do one piece – and that work no longer exists.

“I’ve been an outspoken critic of Arts & Venues not giving enough money proportionately to people of color and people that are local,” he explains. “Most of their big money has always gone to out-of-state artists and to white artists. … I don’t want to sound like a sore loser or something, but that’s the way it is.”

Although he continued to apply for Denver commissions in past years, he doesn’t apply much these days.

“I’m getting too old to be dealing with this, where I’m frustrated about this,” he says. “My files of rejections are a lot bigger than mural commissions that I’ve gotten from the city.”

He’s also baffled that while he was one of the first people to paint a mural in Mestizo-Curtis Park, he has not painted a new mural in the RiNo Art District.

“I know the guy that started the RiNo district there,” Martinez says of Tracy Weil, the artist who helped found the RiNo Art District and is now its director. “I’m disappointed with him, too. For one thing, he told me the first mural he saw down there was my mural at Curtis Park. He said, ‘At some time, I want you to do a mural in the RiNo district. … I’ll consider you doing a mural here since you’re pretty much a pioneer.’ I said, ‘Yeah, duh, I think I should.’ It hasn’t happened yet, and I’m not going to bug him about it. Maybe he just forgets about it, I don’t know.”

“I love his work – he’s an icon,” Weil responds. “We followed up but never heard back from him. Happy to connect, as throughout the year we get several requests for murals, and we’d be honored to have one of his works in the district.” He adds that he’d love for Martinez to apply to be part of Crush, too.

More than fifty years into his career, though, Martinez isn’t eager to fill out applications. Crush’s organizers, he says, should come to him.

Zehb + Plezo work in conjunction with Cromaj on a mural in the Erico Motorsports alley.

Lauren Antonoff

These days, the organizers of Crush are, well, crushed beneath a mounting pile of applications from artists who want in on the action. The eleventh edition of the festival, which runs through September 20, had around 730 people apply for spots; roughly 100 artists were accepted. While some of those artists are from around the country, most of the people painting murals in RiNo right now are from Denver.

Crush is the baby of artist Robin Munro. The festival, and Denver’s street-art scene as a whole, was a latecomer to a movement that swept the world over the past few decades, turning what had been considered graffiti into a legitimate – sometimes too legitimate – art form.

Some think the street-art movement goes back much further than that. Alexandrea Pangburn – who works for the RiNo Art District, helps organize Crush and founded Babe Walls – says the street-art movement originated 64,000 years ago, when Neanderthals chronicled their hunting trips on the walls of their caves.

The street-art movement has long claimed different origins and aspirations from those of the Mexican and Chicano muralists, who situated themselves from the beginning in a fine-art tradition. But there are commonalities: All of these artists paint walls, they often make political statements, and their work shapes how a city defines itself, whose stories matter and whose are erased.

They’ve also become more popular with local governments, which began recognizing that street art can be used as a graffiti-prevention tool. Graffiti writers were less likely to tag a mural than a blank wall, and if they were paid, they were less likely to vandalize property. In 2009, Denver Arts & Venues launched the Urban Arts Fund, a graffiti-prevention program funded by the city’s public-art program that has recruited more than 4,500 youth to work with artists who have painted 350-plus murals around Denver, covering over 500,000 square feet of walls, canals and other public spaces. While the program has been a big hit over the past decade, the fund is currently on hold as the city deals with COVID-19 restrictions and Arts & Venues suffers through severe budget cuts.

Mural by Edica Pacha at 2347 South Street in Boulder.

Evan Sem

Government officials haven’t just used street art to prevent graffiti, however. During the coronavirus pandemic, some state agencies are embracing it. The Colorado Tourism Office, for example, has recognized the explosion of murals around metro Denver, and is now working with Colorado Creative Industries on travel itineraries focusing on outdoor art that will persuade Coloradans and out-of-state visitors alike to see these works for themselves. “We definitely see the opportunity to shift from indoor spaces to outdoor spaces,” says CTO director Cathy Ritter, who notes that a tour along the Colorado Creative Corridor was already one of the agency’s most popular offerings. Soon there will be more such routes shared at colorado.com.

In recent years, politicians, developers and other boosters have taken advantage of the confluence of art, politics and economic growth to push “creative placemaking,” a raging movement in which they collaborate with artists to shape a neighborhood’s image and attract investment.

Since Denver Chicano muralists claimed the west side as their canvas decades ago, nowhere has creative placemaking been on display as blatantly as in the RiNo Art District. Through murals, the arts nonprofit has carved out what many newcomers consider a neighborhood of its own tucked into what is officially Five Points.

A mural by Max M. Coleman on the Larimer Street side of Crema Coffee House.

Lauren Antonoff

Through Crush and the work of the district, industrial warehouses and new developments became canvases for all manner of creative expression: pop art, abstract designs, even activist statements. As the area became popular, developers bought up old warehouses, displacing many of the artists and galleries that had called RiNo home, and built more new developments that attracted new residents. Trendy restaurants and bars popped up, and RiNo became the hottest spot in town.

“We track that it drew 1.5 million people a year, the murals alone,” says Weil. “That’s throughout the whole year.

It’s a destination. We still have galleries and studios and things like that, but people respond to the murals as a big draw, and they frequent those locations and shop at the galleries and studios. It’s really been beneficial to creating a place that people want to go and take a selfie. It’s really created a great draw. A lot of the businesses see the value in that.”

Over Crush’s eleven years, the artists painting the murals have been paid, developers have profited and the city has gained another argument for calling itself a world-class arts destination. But along the way, the festival has also attracted plenty of criticism, both inside and outside RiNo.

A Crush Walls mural by Diana “Didi” Contreras in the S+P Parking Lot on the northwest side of Larimer Street.

Lauren Antonoff

Artists complain that they don’t get enough credit for their work: People shoot those selfies by the murals and never tag or mention their creators. Businesses sometimes use the paintings as backdrops for ads – which has led to copyright fights in court. Earlier this year, Miami artist Diana “Didi” Contreras sued Illinois-based Cannabistry Labs for using a photo of a mural she painted at the 2019 Crush in an Instagram ad without permission or payment.

Lucha Martinez de Luna – Emanuel Martinez’s archeologist daughter, who heads up the Chican@ Murals of Colorado Project and serves as the first curator of Hispanic, Chicano and Latino History at History Colorado – blames Crush and the RiNo Art District in part for the gentrification of Five Points, Curtis Park, Globeville and Elyria-Swansea. She contrasts the murals of the Chicano movement with the ephemeral pop art of Crush: Chicano artists created the murals to preserve their community; the new generation of street artists too often cheerfully paints over work in the name of creative expression, creating economic violence in the process.

Martinez and others argue that Crush should spend less money bringing in international artists and put more cash into the hands of artists from the surrounding neighborhoods. Yet Weil says that’s what the event has been doing all along.

“It’s always been a local festival, and primarily most of the artists are from Colorado,” he says. “Sometimes we have international artists come, but this year we’re staying mostly local, with ten or twelve artists driving in or flying in through the country.”

Local muralist and sculptor David Ocelotl Garcia wishes that the new generation of street artists involved in Crush would steep themselves in the traditions of Denver’s mural scene and honor the indigenous artists who have been painting here for decades. “What I see a lot with the Crush murals is a lot of big paintings, which are cool,” he says, then adds that it’s not cool when they undermine longstanding communities of color. “Some are better than others, but they – for lack of a better word – are perverting the essence of muralism, which is very disrespectful, but also comes from a lack of knowledge.”

These new murals need more story and a better reason to take up so much of the city’s landscape, he argues.

Another recent criticism of the street-art scene, and Crush in particular, is that it has failed to include people of all genders. That’s what inspired Pangburn to start Babe Walls, a festival run by women and non-binary artists.

Pangburn, who was born in Kentucky and spent a few years in Ohio, moved to Golden in 2017. She started working with the RiNo Art District and eventually Crush as an artist and then an organizer. “There wasn’t a lot of representation for women and non-binary,” she recalls. “There were a few artists I’d met in my work at RiNo Made. I wanted them to be a part of this vision I have that would be a women-run festival and would be all women and non-binary.”

Alexandrea Pangburn is the founder of Babe Walls.

Crush Walls

Starting in November 2019, she and a group of artists began organizing that event. They hooked up with Christina and Mike Eisenstein and Peter LiFari, who manage low-income housing for families and own several large-scale apartment buildings in Westminster. The Eisensteins and LiFari lent their outside walls to a festival that the organizers scheduled for May but pushed back to August because of COVID-19.

Throughout the summer, Babe Walls organizers reached out to the neighbors through bilingual letters, trying to get them to buy into the project.

“It’s a fairly large Latino community up there,” Pangburn says. “We were having to work with language barriers, of course. … Because this was a residential neighborhood, we were coming into these people’s community. I wanted to do the best job we could to make sure we weren’t invading.”

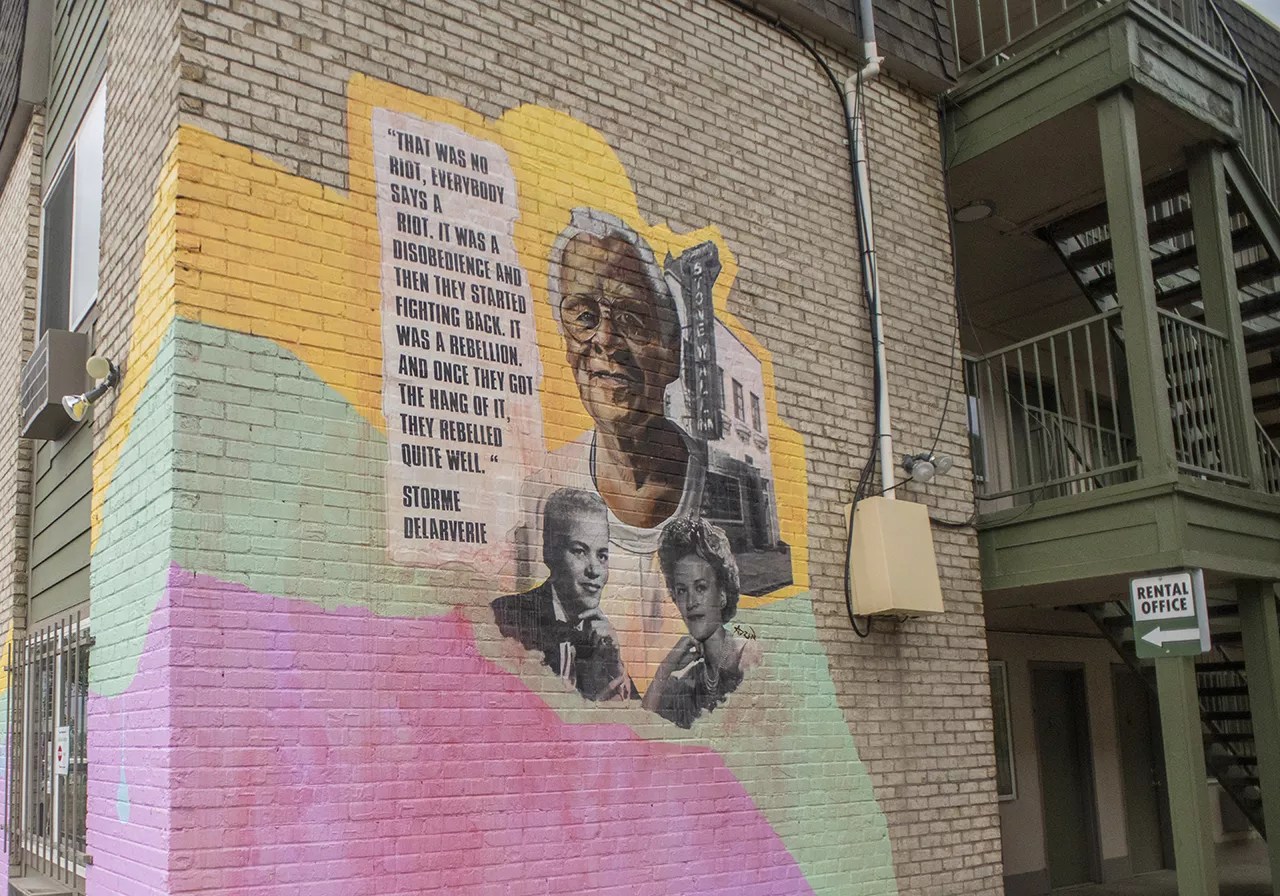

A diverse lineup of more than two dozen female and non-binary artists wound up painting those Westminster walls with colorful murals. Chelsea Lewinski created a massive black-and-white portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe, Kaitlin Ziesmer painted charming birds wearing helmets, and Adri Norris wheat-pasted revolutionary portraits of Ella Baker and Stonewall uprising veteran Stormé DeLarverie. Spectators came in to watch the artists work – 150 people at a time because of COVID-19.

Residents displayed a mixed response to the hundreds of art lovers who watched the artists paint outside their apartment windows, says Pangburn. Many were excited and talked about how the festival and murals made them feel safer, while others were irked by the intrusions. One artist found herself in a confrontation with a resident, but the spat ended amicably.

When Babe Walls attempts to go national – a goal for the project – all of those experiences will prove valuable lessons for how artists from the outside can be more respectful to the communities where they are painting. And while gender parity in the street-art scene continues to be an issue, Pangburn is seeing progress. “This year, more than ever, I’ve seen more women in the scene be able to have that space,” she says. “I don’t know why that is – because this year has been so crazy anyway.”

Adri Norris at work at Street Wise Boulder.

Peter Kowalchuk

Colorcon, the street-art festival in Denver’s Golden Triangle neighborhood, included an all-women and non-binary lineup in 2020. Street Wise Boulder, a mural festival also in its second year, says it is committed to equity and diversity.

Even Crush is doing better, Pangburn says: “I’m on the Crush committee. Being a part of that organization has really helped gender equity. Last year, the first year I had started helping, was one of the highest years of women we’ve had so far.” This year it’s even higher. The festival also has more BIPOC people represented in the lineup than in most years, says Weil.

But broader representation among the artists is not enough, argues Martinez de Luna. More neighbors need to be involved, too.

“There is this danger of everybody trying to reach out to these marginalized communities,” she says. “That danger is making these symbolic gestures. Oh, we’ll just add more people of color on the list…. Meanwhile, their communities are completely being displaced and the gentrification is going on. How can you justify you’re going to do this huge mural festival? You sprinkle in some people of color, and that takes care of the whole problem? Those conversations – we don’t have those kinds of conversations. They’re uncomfortable, and money is always involved.”

Martinez de Luna has been keeping an eye on emerging mural festivals, looking for people who are doing it well.

“I went to Babe Walls,” she says. “The name was terrible, but it was an interesting concept to have just female muralists – but at the same time, it felt strange. These random walls on these newer apartment buildings – there was really nobody from the community involved. It was just a lot of people going to visit the artists. Crush feels the exact same way. There are a ton of people there, but I don’t see people from the community there.

That’s probably because nobody’s left. Everybody’s gone. When I talk to elders in the community, working at History Colorado, they’ve never heard of Crush. They don’t know what that means. They don’t know about RiNo. They avoid those areas entirely. A lot of communities can’t afford a coffee there, let alone go there, look at murals and have something to eat.”

Mural by Danielle SeeWalker at 72nd Avenue and Hooker Street.

Evan Sem

Plenty of groups have continued the tradition of community-based murals and art for years, de Luna says. There’s the decades-old work of the Chicano Humanities and Arts Council, one of the galleries central to the foundation of the Art District on Santa Fe, which has provided an exhibition space for many muralists. Anthony Garcia and the Birdseed Collective have organized community-based murals with youth in Globeville and beyond since 2009. And D3 Arts and the Westwood Creative District, which are aspiring to incorporate murals and art into the neighborhood without displacing residents, have become a home for a younger generation of artists.

Some festivals are doing better than others, she adds, name-checking the Fraser Mountain Mural Festival and Street Wise Boulder, though she wishes the latter included more elders.

Mural of Storm

Evan Sem

Leah Brenner Clack, the head of Street Wise Boulder, says that her festival brings artivists committed to social justice to what has become a gentrified, wealthy, white university town. And while civil-rights-era artists aren’t represented, there were artists over forty on the roster, she notes.

Clack moved to Boulder 25 years ago and says she made it her life’s mission to champion artists in the city. While residents haven’t always been receptive to murals, in recent years they’ve seen how street art has transformed other cities’ urban landscapes for the better, and have been moved by the political content of the work.

“Art has always been historically tied to protest, change,” Clack says. “It’s been a voice for the people. People and artists are using this platform more than ever to express themselves, to unite.”

Part of what makes her festival unique, she adds, is that she doesn’t just invite tried-and-true artists. “There were artists in the festival this year who were painting their first mural ever,” she says. “It’s a big opportunity when artists get that chance. I feel like it’s so important to be open and inclusive.”

But not everybody on the scene thinks that inexperienced artists should have a crack at their own wall before working their way up through the ranks.

Mural by David Ocelotl Garcia at the Dairy Arts Center, 2590 Walnut Street in Boulder.

Evan Sem

David Ocelotl Garcia, who says he’s a traditionalist when it comes to what goes on city walls, hopes people study with mentors and don’t just watch a YouTube video, work up a fast design in Illustrator without thinking about what it means, and barf it onto a wall.

“The hard part there is trying to convince [young artists] that learning the basics, going back to the fine art and connecting with your medium physically is very important,” he says. “Murals now, they’re all digital all the way through. … They’re making these Illustrator murals, where they go on a computer and Photoshop it in somehow. They find a way to separate the color. It’s really technical and very digital.”

It’s also inauthentic, he says. He likens the process of painting to a sweat lodge, and argues that people have to be physically engaged with the work in order for it to be meaningful.

“A sweat lodge is a physical thing,” he says. Painting over digital projections is “like saying we’re going to do a virtual sweat lodge.”

Along with the digital art comes a troubling disposability, he adds, pointing to how each year, artists paint over the murals from previous years at Crush.

In part, this is because there are so few blank walls left in the RiNo Art District. But it’s also because muralism is impermanent by its very nature, says Weil, and many of the artists like it that way. “Most murals are temporary,” he explains. “That’s sort of the nature of the beast. The mural and the street-art movement was started by graffiti writers, right? That’s how it came together in the first place.”

But the history of muralism, as Garcia understands it, doesn’t come out of graffiti writers. Los Tres Grandes and local elders like Martinez paved the way, even if younger artists have forgotten them.

“People are coming in with this mentality that everything is replaceable,” he says. “That’s the mentality people are bringing in, especially business owners and even developers. They come in and say, ‘We’re going to remake this place. We’re going to bring in our own vision and make our own community.’ It’s a very dictatorship mentality. That’s something very sad. It’s been happening forever here. We talk about native struggles in the states and everywhere. If you come in with this mentality of conquest, man, that’s old. We’ve been going through that for so long now, it’s crazy.”

Murals by Kaitlin Orin and Kaitlin Zeismer at 71st Avenue and Hooker Street.

Evan Sem

Nowhere are those tensions more evident than in northwest Denver, where Italians, then Chicanos and now white people have made themselves at home.

“Ever since they’re developing Highlands, [Chicanos] have been being displaced,” says Garcia. “I came in not that long ago to create this painting at the gazebo there at La Raza [Park]. They’re going to call it now Plaza de La Raza instead of Columbus Park. I kind of came in there when it was pretty much Highlands full force, and here I am painting Mexican-American history. It’s interesting to think about. If a lot of the community here is predominantly white now, it’s going to be an interesting thing. I don’t know the implications.”

Cultures also collided when the Mana Supply Co., a soon-to-open dispensary, painted over one of his murals off Federal Boulevard. The lease should have protected the painting, Garcia says, and when dispensary workers whitewashed it, they violated that contract.

Garcia and the Chican@ Murals of Colorado Project confronted the business owner, Matthew Volz, explaining what the mural meant to the community and the damage his business had done. He apologized.

“Right now, we’re negotiating to have David repaint the mural,” Martinez de Luna says. “If that happens, it will be the very first time it happened. We’re so tired of this now.” After all, Chicano murals, including some by her father, have been painted over by new building owners and renters many times before.

At first, Garcia says, Volz was receptive to the idea of paying him to repaint it – but then he saw the $60,000 price tag and quit responding to communications. (Volz has not replied to Westword‘s request for comment.)

When Martinez de Luna, who is advocating for legal protections for public art, thinks about the disposability of murals and street art, she worries about what it means from an archeological perspective.

“I have a really large project in Mexico,” she explains. “I’m excavating a site that’s 5,000 years old, and I come home, and I go to the north side of Denver, and it’s like, wow, my whole community that I grew up with is gone. And here I am excavating this site that is 5,000 years old. When you think of an archeological site, what do you excavate? The elite houses, monumental art, public art. If you come to Denver in 1,000 years or 500 years or even 50 years, there will not be any public art of Chicanos. There will be no trace of them. The same in Globeville and Swansea. It’s cultural erasure. They just never existed.”

That’s her fear. But she’s also holding out hope that her efforts will help preserve Chicano art and history in this city, and that artists and funders can find a better way to move forward.

As part of her work with the Chican@ Murals of Colorado Project, she’s bringing younger Latinx artists together with veterans to collaborate on a mural in La Alma/Lincoln Park, where her father’s works have stood for half a century.

When she held a meeting about the effort earlier this year, 35 artists showed up, many of them young. She plans to have them work with master artists such as Tanguma, EspinoZa and Martinez on a project that will bridge the generations. But funding for this less trendy work is harder to come by than money for Instagram-friendly eye candy made by the hot new artists.

“I’m racing with time trying to create some of these opportunities with muralists to paint their last murals,” she says. “It’s so heartbreaking to see all this money funneled into these festivals. Why don’t they consider their elders?”