Photo by Michael Roberts

Audio By Carbonatix

The just-concluded 45th annual Denver Film Festival was the first since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic to be an entirely in-person experience, and over the course of its twelve-day, November 2-13 run, there were plenty of indications that patrons were eager to watch movies on something other than Netflix. Not all of the seventeen screenings or events I attended were packed; less than half the Ellie Caulkins Opera House was full for the emotional opening-night presentation of the ambitious but flawed Oscar hopeful Armageddon Time. But nearly every seat was occupied at several screenings, and even the most obscure flicks attracted a sizable number of cineastes who seemed to savor the experience even when the main attractions fell short.

To get a sense of the 2022 edition, here’s a look at my DFF45 diary:

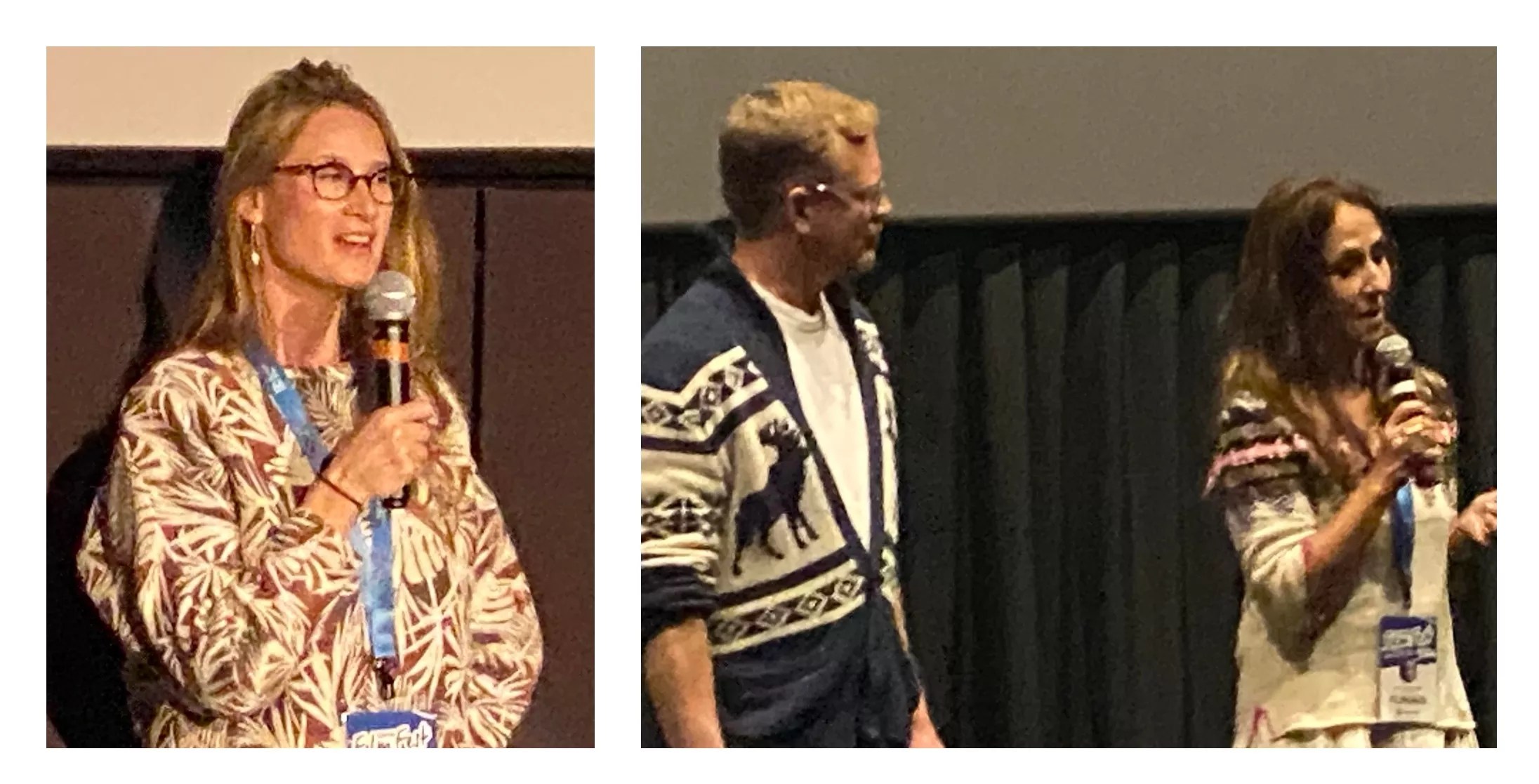

Three How to Blow Up a Pipeline creators (from left): producer Isa Mazzei, writer/producer Jordal Sjol and director Daniel Goldhaber.

Photo by Michael Roberts

How to Blow Up a Pipeline, Thursday, November 3, at the AMC 9 + CO 10, is the latest from Boulder director Daniel Goldhaber, and it offered a primer on how to do a lot with a little. The film’s budget likely wouldn’t have been enough to cover the cost of Tom Cruise’s masseuse on Top Gun: Maverick, yet Goldhaber was still able to create a tense, engrossing tale about a group of climate activists dedicated to taking radical action. The movie’s title is perfectly descriptive, with the camera tracking an attempt to stop oil flow in one section of Texas by explosive means with such precision that some viewers may fear it will give similarly inclined folks some bad ideas. But while the assorted characters tend to top out at two dimensions, the talented cast, which includes Forrest Goodluck, Sasha Lane and Jake Weary, makes them compelling even when their motivations seem too pat, and the fast pace and a propulsive score that recalls early John Carpenter helps compensate for the financial limitations. Afterward, Goldhaber, on hand for a Q&A, said he was inspired by heist movies, and he clearly did his influences proud.

Empire of Light, Friday, November 4, at the Ellie Caulkins Opera House, is being promoted as a valentine to movie palaces of the past, but don’t go into it expecting Cinema Paradiso. The latest from director/writer Sam Mendes is essentially the British twin of Armageddon Time, since both films are set in 1980 and revolve around race relations. Olivia Colman, who acts as if the obvious effort she’s exerting should earn her another Academy Award nomination (she’s probably right, since Oscar voters seldom reward subtlety), plays Hilary, a lonely, unhappy woman struggling with mental health issues who meets Michael Ward’s Stephen, a Black fan of the two-tone ska movement who’s targeted by skinheads and National Front thugs. The couple’s tender but not wholly believable relationship forms the spine of the story, which seems so tangential to the theater around which the action revolves that my son, who accompanied me, saw the entire enterprise as something of a bait-and-switch – and he’s got a point.

Butterfly in the Sky, Saturday, November 5, at the AMC 9 + CO 10, is proof that sincerity and a good subject can take filmmakers a long way. The documentary traces the history of Reading Rainbow, a PBS educational program that starred LeVar Burton, fresh from his television debut in the slavery epic Roots. There’s nothing particularly revolutionary about the way directors Bradford Thomason and Brett Whitcomb present the material; they lean heavily on interviews and clips. But the snippets, including a song in which the members of Run-D.M.C. rap about how much they love books, are charming, and everyone involved, including Burton, so obviously had their hearts in the right place that those watching can’t help but feel the love.

The Grab, Saturday, November 5, at the AMC 9 + CO 10, is a documentary that takes on a much heavier topic: how food and water are replacing fossil fuels as the motivator behind many global conflicts. The focus is on a nearly decade-long probe conducted by Nate Halverson on behalf of the Center for Investigative Reporting, with director Gabriela Cowperthwaite using him as a common thread to weave together examples of the phenomenon in the United States, Africa and war-torn Ukraine. The film presents scads of convincing information – too much, in fact. Rather than narrowing their focus, Cowperthwaite and Halverson, who were present for the screening, keep broadening it to the point where the the doc becomes something of a data dump. Viewers will learn a lot, but only if they’re willing to laboriously sift through the results rather than simply absorbing them.

(From left) Battleground director Cynthia Lowen and The Grab producer and subject Nate Halverson with the documentary’s director, Gabriela Cowperthwaite.

Photos by Michael Roberts

Battleground, Sunday, November 6, at the Sie FilmCenter, looks at the fight for and against abortion rights in the two years prior to the U.S. Supreme Court’s overruling of Roe v. Wade. But what makes the documentary unusual is the decision by director Cynthia Lowen to front-load material from anti-choice boosters, advocates and spokespersons, who are allowed to espouse their views for nearly half the running time without substantial challenge or pushback – and they get more opportunities for close-ups even after their ideological opponents join the spotlight. Lowen, who spoke after the screening, emphasized that she is a fervent advocate for abortion access, but she also confirmed that the interviewees who feel differently have all seen the movie and like it – and no wonder, since they’ve been afforded a roomy platform. Whether the neutral presentation gives pro-lifers enough rope to hang themselves or serves as an informercial for their opinions will be up to each viewer to determine, but either way, the effect is unsettling.

The Lost King, Sunday, November 6, at the Sie FilmCenter, is the latest entry in an idiosyncratic subgenre of British film that explores a lovably awkward true-life eccentric’s magnificently odd obsession. (The Duke, a 2020 film about a man who stole the Duke of Wellington’s portrait in part to protest having to pay for a TV license, is a recent example.) The protagonist is Philippa Langley, who waged an ultimately successful campaign to unearth the corpse of King Richard III in large part because she felt Shakespeare’s depiction of him as a cruelly disfigured tyrant was unfair. The plot, assembled by Steve Coogan, who co-stars, is rather slight and uses the dopey gimmick of having Richard’s apparition regularly appear before Philippa. Still, the wobbly contraption holds together surprisingly well, thanks largely to star Sally Hawkins and director Stephen Frears, both of whom tend to be forgotten when lists of current cinematic treasures are assembled, even though they absolutely deserve to be included. Quirky and lovely in equal measure.

The Son, Sunday, November 6, at the Sie FilmCenter, could not be more different, or less laudable. The title character is Nicholas (Zen McGrath), and from early on, he makes it plain that he’s going through a terrible mental health crisis that his divorced parents, played by Laura Dern and Hugh Jackman, fail to address in even close to an effective way. Instead, they either dither or offer shallow encouragement or empty gestures as the teen careens ever closer to the metaphorical cliff. The slow march toward the inevitable plays out by way of intermittent outbursts briefly interrupted by a cameo from Armageddon Time star Anthony Hopkins, who won an Oscar for The Father under the supervision of director Florian Zeller. Neither Jackman nor Dern are likely to follow suit owing to the lackluster material, Zeller’s utter lack of visual flair and stereotypical dourness epitomized by the moment when “It’s Not Unusual,” a Tom Jones song used to score a dance scene, is faded out in favor of the most depressing ballad the creators could find.

She Said, Monday, November 7, at the Denver Botanic Gardens, which details the New York Times inquiry into accusations of sexual crimes against Miramax boss Harvey Weinstein, could have been just as much of a slog. But against all odds, the film version of a book by scribes Megan Twohey (Cary Mulligan) and Jodi Kantor (Zoe Kazan) is a model of smart Hollywood adaptation. Rather than channeling Lifetime and hiring an actor to reenact scenes of abuse, director Maria Schrader and screenwriter Rebecca Lenkiewicz smartly take the All the President’s Men approach of following Twohey and Kantor as they try to get enough evidence on the record to make Weinstein pay for his horrendous crimes. Granted, there’s more hugging in the newsroom than most reporters see in a career, and the Times‘s tremendous resources (the paper pays to fly Kantor to London simply to knock on the door of a potential source who hasn’t been answering calls or emails) are taken for granted. But the revelations more than earn this particular love letter to journalism, and the performances are uniformly first-rate – especially the one delivered by Andre Braugher as Times executive editor Dean Baquet, who should send Braugher a thank-you note immediately.

Living, Tuesday, November 8, at the Denver Botanic Gardens, is a ’50s-set British variation on Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru, a 1952 film drawn from Leo Tolstoy’s 1886 novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich – which means there’s not a lot of suspense about whether Williams, a civil servant portrayed by Bill Nighy, is going to wind up in a coffin. But the bitter comes with plenty of sweet. After receiving a terminal diagnosis, Williams considers shaking off his bourgeois malaise and going wild, but he soon comes up with a far more apt way to leave his mark – helping to cut through reams of red tape and bureaucracy in order to create a park in the middle of London’s crumbling inner city. The tone set by director Oliver Hermanus is so low-key that it’s only a step or two removed from silence; Nighy delivers most of his dialogue in a quiet murmur, and with the exception of Aimee Lou Wood’s turn as an upbeat former co-worker, most of his castmates seem to know that raised voices are against the rules. But if there’s a certain sleepiness about the project, Living‘s conclusion offers the happiest sort of sad ending.

The Inspection, Wednesday, November 9, at the Denver Botanic Gardens, co-stars Raúl Castillo, recipient of this year’s DFF Excellence in Acting Award, and in talks before and after the highly anticipated new flick unspooled, he didn’t disappoint. He seemed genuinely pleased by the honor, and if he proved a bit geographically challenged (at one point, he guessed that Snowmass was “north of here”), his description of his winding career path (prior to becoming an actor, he was a fledgling punk-rock musician) was brightened by a sense of wonder and gratitude. But while his work in The Inspection is solid, the film itself proved rather underwhelming. Writer/director Elegance Bratton’s semi-autobiographical study of Ellis French (Jeremy Pope), a queer Black man trying to survive Marine boot camp circa 2005, strikes too many stereotypical beats, with several plot twists, including not one but two problematic shower scenes, corresponding more snugly than necessary with hoary gay-panic tropes. Clumsy staging and a resolution built around an energetically de-glamourized Gabrielle Union as Ellis’s unsympathetic mom that lands with a thud also do damage, leaving The Inspection feeling less like a fresh look at a familiar milieu than a missed opportunity.

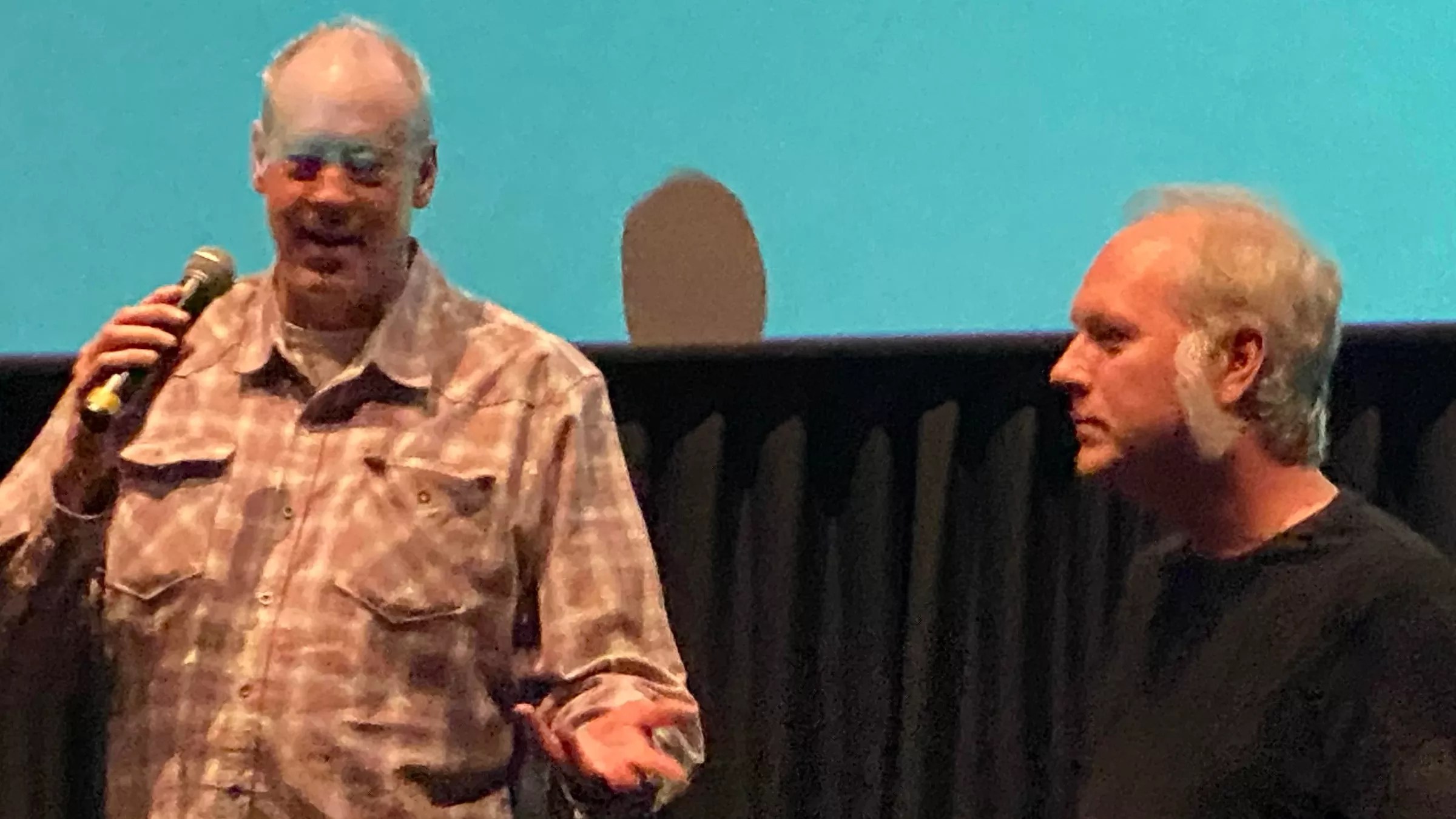

Writer-director Julian Rubinstein and Terrance Roberts, the subject of the film The Holly.

Photos by Michael Roberts

The Holly, Thursday, November 10, at the Ellie Caulkins Opera House, probably wouldn’t have been anyone’s prediction for the festival’s biggest draw. Rather than a star-studded spectacle, it’s a gritty exploration into the repercussions of a Denver-area shooting that took place back in 2013. But writer-director Julian Rubinstein’s adaptation of his 2021 book of the same name attracted a throng of more than 1,000 that was diverse, attentive and enthusiastic. Exuberant applause broke out at the climax of the scene in which Terrance Roberts, a former gang member turned anti-gang activist, was found not guilty of attempting to murder Hasan Jones, an active gangbanger, at a peace rally near the former shopping center that gives the documentary its name, even though Roberts’s presence at the Ellie clearly demonstrated that he wasn’t behind bars. The film itself is raw and passionate, and if its allusions to stealthy conspiracies, political opportunism and the exploitation of a community for profit and prestige are necessarily less detailed on the screen than on the page, the depiction of Roberts’s odyssey still leaves a mark. Afterward, Rubinstein, joined on stage by Roberts, said he couldn’t understand why the overwhelming majority of city officials he’d invited to see the movie had either declined or failed to respond, even though the reason is obvious: It makes them look terrible.

Please Baby Please, Friday, November 11, at the AMC 9 + CO 10, is a minor but lively tribute to early-period David Lynch: a Blue Velvet riff produced with the resources of Eraserhead that’s built around characters whose sexuality starts out fluid and ends up a gas. The performances by Andrea Riseborough and Harry Melling, as a couple who begin to break out of their shells after encountering a street gang whose members seem to have wandered in from a particularly rough-trade revival of Grease, are comically arch, as is a cameo by, of all people, Demi Moore. And if too much of director Amanda Kramer’s enterprise is secondhand, there’s a genuine spark to several quirky musical numbers, including one in which Riseborough cavorts with a series of household appliances. It’s capable of inspiring you to ask your vacuum for a dance.

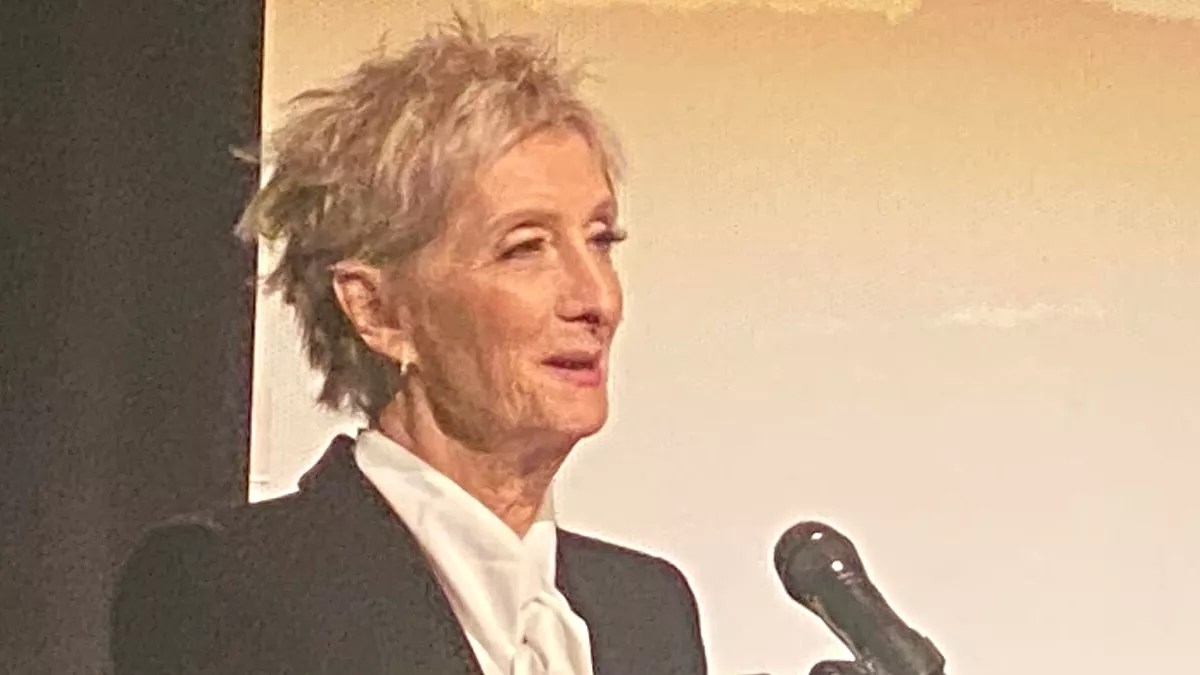

Mark Mothersbaugh autographing a fan’s energy dome and talking about his contributions to Pee-wee’s Playhouse.

Photos by Michael Roberts

An Evening With Mark Mothersbaugh, Friday, November 11, at the Denver Botanic Gardens, gave an overflow crowd a chance to hang out with the co-founder of the iconic new-wave band Devo, who’s gone on to become a prolific composer for film and television; his credits range from Pee-wee’s Playhouse to Thor: Ragnorak. Mothersbaugh is in his early seventies now, but as he mingled with fans before the show started, happily autographing one fan’s vintage Devo “energy dome” at one point, the joyful obstreperousness of his younger days was on full display. The presentation melded conversation and video snippets, and Mothersbaugh rambled at times, albeit amusingly: He actually had trouble recalling the name of a certain centrally located park in New York City. But he also shared loads of diverting anecdotes, revealing, for example, that he slipped subliminal messages into commercials he scored (a Hawaiian Punch spot was embedded with the phrase “Sugar is bad for you”) and satisfied director Wes Anderson’s desire for a new melody similar to a previous ditty by playing the old one backwards. That’s our kind of de-evolution.

Andy Falconetti of Sissy Fuzz and the Apples in Stereo’s Eric Allen at the screening of The Elephant 6 Recording Co..

Photo by Michael Roberts

The Elephant 6 Recording Co., Saturday, November 12, at the AMC 9 + CO 10, is a documentary about which I can’t pretend to have the slightest objectivity. I was the music editor at Westword during the 1990s, when the cheerfully inventive Elephant 6 collective was in full flower, and I took endless shit for the amount of coverage we lavished on acts such as the Apples (starting before they added “in Stereo” to their moniker), the Minders, Dressy Bessy and so many more, rather than hyping some hot hair band playing Herman’s Hideaway. As such, director C.B. Stockfleth’s salute is basically a feature-length argument that we were right all along. The music continues to sound great, and the depiction of camaraderie among the assorted acts was delightfully free of bitterness and backbiting. Afterward, Andy Falconetti of the Elephant 6-adjacent combo Sissy Fuzz and Apples bassist Eric Allen kept the good feelings flowing – and Allen even hinted at the possibility of new music from his group. Please make that come true.

Sheila McCarthy accepting the Denver Film Festival’s career-achievement award prior to the screening of Women Talking.

Photo by Michael Roberts

Women Talking, Saturday, November 12, at the Ellie Caulkins Opera House, finds director Sarah Polley using a 2018 novel by Miriam Toews to explore the responses of Mennonite women to persistent and horrific sexual abuse by males in their community circa 2010. Polley elicits performances that are very good (Rooney Mara), superb (Ben Whishaw, Judith Ivey and Sheila McCarthy, who received the fest’s career-achievement award and spoke before the film ran), and absolutely riveting (Jessie Buckley and Claire Foy are both Oscar-worthy), and her imagery merges the bucolic with the shocking. Yet these assorted elements never truly jell. The script is the equivalent of a play opened up only slightly for a different medium, with the overwhelming majority of the action taking place in a hayloft, and it becomes obvious so quickly what the women must do (despite the protestations of a character played briefly by Frances McDormand, a co-producer of the film) that the inherent drama of the premise soon sags. An impressive acting showcase that doesn’t quite work as a movie.

Turn Every Page: The Adventures of Robert Caro and Robert Gottlieb, Sunday, November 13, at the Sie FilmCenter, documents the half-century-long working relationship between Caro, author of The Power Broker, an influential profile of Robert Moses, and a multi-volume exploration of President Lyndon B. Johnson that stands among the greatest-ever political biographies, and Gottlieb, arguably the most celebrated book editor of the era. At 87, Caro is still trying to complete the final book of his LBJ series, while Gottlieb, 91, is hoping to hang on long enough to add his touch – and director Lizzie Gottlieb (the latter’s daughter) presents them as the last of a dying breed. Humor abounds: Caro still uses a typewriter and carbon paper, while Gottlieb insists on editing with a pencil – and discovers near the end of the film how difficult it is to find one in a 21st-century publishing house.

The movie will never be a blockbuster, but those who saw it were clearly glad it exists – and equally pleased that such obscurities are championed by the Denver Film Festival.