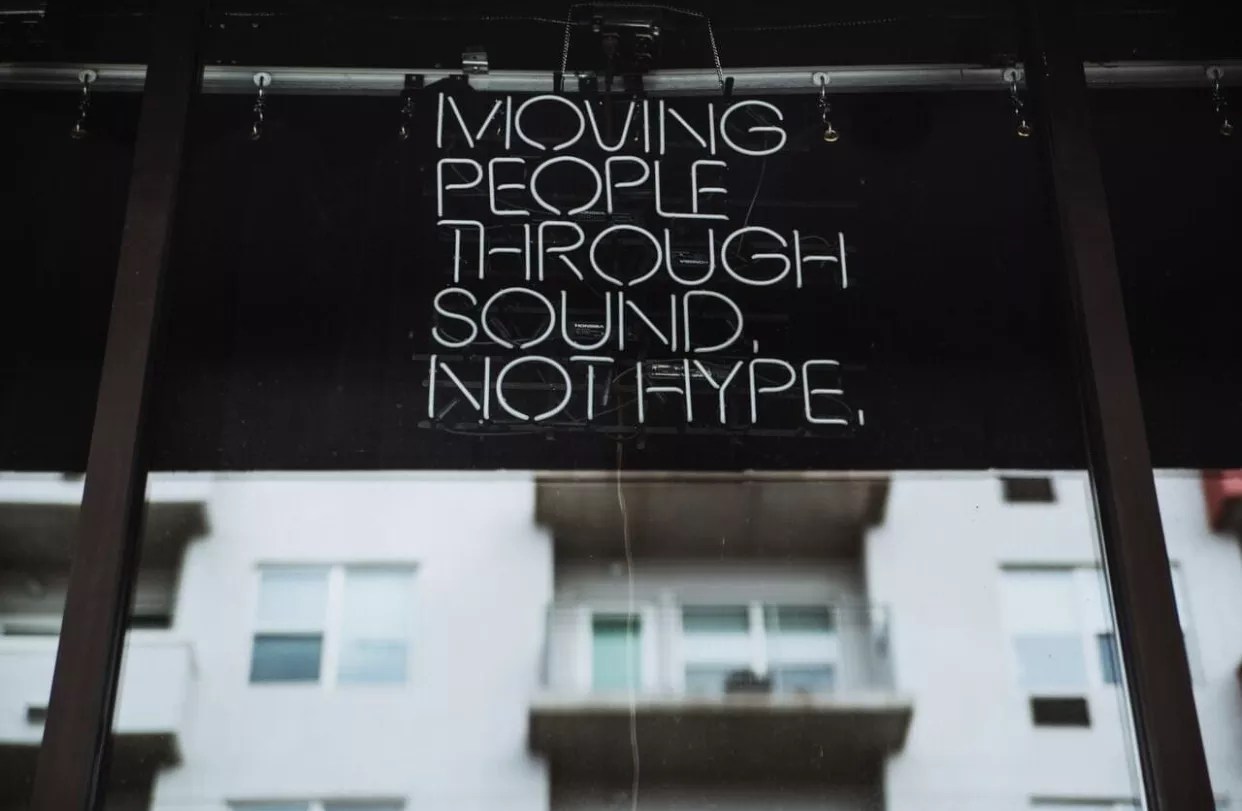

Sub.mission

Audio By Carbonatix

Imagine it’s 2009: People are talking about this new type of electronic music called dubstep. People are using phrases like ‘the metal of electronic music’ and ‘that wub wub sound.’

Love it or hate it, dubstep was undeniably different, heavy and ear-blisteringly unrefined in a time when electronic music was polished to a crisp. While the rest of the country was beginning to take notice of this “new sound,” it had already taken root in the Mile High City, cementing Denver as a hub for emerging EDM.

Now imagine it’s 2012: Dubstep is in every facet of mainstream culture. It’s in everything from car commercials to the headlining act of every major electronic music festival. What was once a novel and captivating experiment in noise and destroying trends became, well, background noise.

Looking back on the subgenre’s early time in the music scene, the question everyone was too busy having a good time to ask was: Why Denver? While the sound was blowing up in Europe and places like New York and Los Angeles, Denver was right there on the forefront. Who was responsible?

The answer is Nicole Cacciavillano, owner of the Black Box and one of the first promoters in America to book European dubstep artists. “It happened so fast. For so long we were throwing parties that no one had any idea what dubstep was. We were selling out Cervantes’, and none of the corporations had any idea what was happening. It was like this tightly knit unit of people even though it was a thousand-plus capacity at the time,” she recalls. “We were just doing it; we were loving it. That was 2010, 2011. Those days were the best, before it got tainted. That’s what the underground used to be. Now you say dubstep and everyone knows exactly what you’re talking about.”

Cacciavillano grew up in Philadelphia, where she gained an appreciation for drum-and-bass music and the rave scene. “I was super into the underground culture. I just liked the whole idea of the map points and the hidden parties, and the choose-your-own adventure,” Cacciavillano reminisces. She attended Mansfield University on a basketball scholarship and studied education. After college, she was working as a teacher when she visited Colorado for spring break (after a Google search of Colorado drum and bass), and fell in love with the place. She relocated to Denver around 2004 and jumped right into the electronic-music scene.

The Black Box is Denver’s place for EDM.

Sub.mission

Cacciavillano’s first show was in 2007 at Quixote’s (which she would eventually own and rename the Black Box in 2016), with U.K. dubstep pioneers Hatcha and Benga. She would continue to champion dubstep in Denver, a sound her booking and talent agency, Sub.mission, would be known for.

“At the time, dubstep didn’t really exist in America. And so myself and a couple of other promoters from around the country started bringing in artists, started pushing the 140 sound out here and trying to find venues that would let us bring in sound systems,” recalls Cacciavillano. “Back in those days, we didn’t have any choice but to book someone from overseas to come play. They would have to ship their records, because it was still turntables at that time.”

This practice, while logistically difficult, would prove to be the right recipe for building a vibrant underground electronic music scene. Dubstep slowly found a home in Denver as Cacciavillano began throwing shows at bigger and bigger venues until she began working with AEG and reached the ultimate prize as a promoter: Red Rocks.

“The first Red Rocks show I did was Global Dub [in 2012], and I remember looking up from back stage, and it was that moment where I was like, ‘Holy crap, dubstep is at Red Rocks,’ and I looked up into the crowd and all the glow sticks, and I started crying,” reminisces Cacciavillano.

While it was a height for the genre and pinnacle of her promotional career, the experience was bittersweet. Dubstep started out as anti-establishment, but not so much anymore. It was supposed to be too weird, too noisy for corporate America, but here it was at one of the most well-known venues – and there was no going back. “It was not how I would’ve envisioned this underground sound that came from the U.K. would make its debut,” Cacciavillano says. “It was also the moment when I knew everything was changing: The sound had penetrated the mainstream market. But the bigger the mainstream, then the bigger the underground – which is great for me, so I can’t really complain about it.”

Leading up to the explosion in dubstep’s popularity, Cacciavillano was working as a teacher and continuing her education until her two lifestyles could no longer co-exist. “I got my master’s in working with behavior, so mainly with kids with autism, but with behavioral issues as well. After that I went on to get my doctorate, and all I have is my dissertation left, but I quit teaching…around 2011 to do music full-time,” recalls Cacciavillano. “Because by then it was insane. I was the only dubstep promoter in Denver. We were doing a weekly Electronic Tuesdays, which turns thirteen this year, then going in to teach on Wednesdays was not fun. And it wasn’t fair for my students for me to show up tired.

“Surprisingly enough, my behavior background works really well with drunk people,” she adds. “I can’t say my training has gone to waste at all.”

Cacciavillano’s experience seeing dubstep go corporate led her to the realization that if she wanted to maintain a creative aesthetic for the music as she saw it, she would need her own venue. She opened the Black Box in 2016 and launched the Sub.mission talent booking agency, which now represents around eighty electronic artists across the globe. She says she bought a venue with small capacity because it maintains the “culture” of dubstep. “It’s no pre-recorded sets, it’s not people who are so blown out from playing everywhere who have no time to produce music and keep up with themselves. What we look for is just raw talent,” she explains. “People who care, people who have passion, people who are still in it for the right reasons. People who are still pushing boundaries.”

Like most venues and entertainment companies, particularly such independent ones as the Black Box, the COVID pandemic left Cacciavillano with plenty of soul-searching to do. While there are many new challenges as a result, she doesn’t see them all as bad for the industry. If anything, she sees it as a chance for music fans to regain some control over the spiraling music festival industry.

“Because of oversaturation in Denver and America…fans are really going to start to dictate what’s what – because they’re not spending money on the same old, same old,” says Cacciavillano. “If they have already seen an artist and it wasn’t special, they’re not going to spend their money. I think unless festivals can come up with creative solutions and lineups that are different from each other, then people aren’t traveling. It’s the same with large-scale events. I know right now large-scale events are struggling with attendance because people just don’t want to go out as much. They don’t drink as much as they used to, they’re not partying as much as they used to. Kids just don’t have enough money to go out every night of the week like they used to.”

With this in mind, Cacciavillano reiterates what it means to be an independent venue and her hopes that fans will see the value in what it means to have a place representing the underground music scene.

“When you’re working with an independent promoter, there’s only so much money. We don’t have investors. Please buy tickets, buy a drink, alcoholic or non-alcoholic, it helps us stay open. It’s like anything: Once the corporations get involved, it changes things. You know, people are very happy to play one-hour sets for hundreds of thousands of dollars,” she says with a laugh.

But at the Black Box, she says, “when artists play, they’re still playing for the fans; they’re playing for the culture.”

Find shows at the Black Box, 314 East 13th Avenue, on its website.