Jay Vollmar

Audio By Carbonatix

On March 29, 2017, dozens of parishioners hastily gathered at Our Lady of Visitation. They weren’t at the little Catholic church in unincorporated Adams County to worship, commune or celebrate as they – and some of their parents, and even their grandparents – had for decades. They were there to confront three invisible representatives of the Archdiocese of Denver.

After a member of OLV’s parish council described the church’s promising financial health, a longtime congregant began to address the crowd. He spoke with the panache befitting a politician known to raise a little hell.

“I’m very honored to be here tonight, and I’m glad we’re videotaping this,” said former Denver mayor, U.S. Transportation Secretary and U.S. Energy Secretary Federico Peña, an OLV member for thirteen years.

Speaking through a small mic hooked to his tan blazer, Peña reminded parishioners of the day in November 2016 when Monsignor Bernard Schmitz, the archdiocese’s de facto head of community relations, and the Reverend Giovanni Capucci, a lawyer for the archdiocese, arrived unannounced at a church subcommittee meeting and informed members that by spring 2017, the archdiocese was going to terminate the one Mass per week held at Our Lady of Visitation and merge the congregation with the nearby, much larger Holy Trinity, at 3050 West 76th Avenue in Westminster.

As Peña spoke, he occasionally glanced at three empty chairs at the front of the room as if their intended occupants – Schmitz; Father John Paul Leyba, who had delivered Mass at OLV once a week for the previous six years; and Archbishop Samuel Aquila, who’d succeeded Archbishop Charles Chaput in 2012 – were present.

“Think about that,” Peña told the crowd. “It was announced. There was no discussion. I don’t recall anybody ever coming and asking you your opinion, our opinion, to get our feedback.

“But, Archbishop,” he continued, turning his attention to the empty chair in the middle bearing Aquila’s name, “you did not come to make that announcement.”

Federico Pe

Anthony Camera

After Peña finished, other parishioners spoke on behalf of Our Lady of Visitation, making their case to the invisible judge and jury. One speaker commended the church for helping him get through his wife’s death. Another recalled watching her father, Benito Garcia, and some of the other men from the surrounding Goat Hill community gut two streetcars that they used to build a church for the poor, mostly Latino, mostly agricultural workers who tilled fields in north Denver after World War II.

During their unannounced visit, Schmitz and Capucci had laid out reasons that the archdiocese wanted to cease Mass at Our Lady of Visitation. Considered by the archdiocese a “mission” of Holy Trinity, OLV had been sharing administrative staff and priests with the larger church since the late ’50s. But a recent shakeup at Holy Trinity had left the staff stretched too thin, and Father Leyba no longer had time to deliver Mass at both locations. They said the archdiocese wanted to focus on building churches in Denver’s growing suburbs. They argued that OLV’s congregants were too old.

The stunned parishioners quickly began fighting for their church. They raised money to keep OLV going. They started reaching out to retired priests who might be willing to offer Mass once a week at OLV. They encouraged members of the congregation to write to the archbishop over Christmas and through the new year, asking him to visit the church so that he could see for himself the community that had grown there over generations. But mostly, they searched for a sign that Archbishop Aquila was willing to listen and negotiate.

They didn’t get one. In March, Peña finally called a friend, a lawyer who represents the archdiocese, to find out whatever he could about the fate of the church. To his surprise, he learned that the archdiocese was planning to send representatives to a meeting scheduled two weeks later, when they’d officially announce the closing of Our Lady of Visitation.

Peña and Jerome DeHerrera, an attorney and OLV member, asked to meet with Father Leyba and Monsignor Schmitz in advance to try to come up with some sort of compromise. “We said, look, there are two ways we can deal with this,” Peña recalls. “We could have a big public fight and everybody will be very embarrassed, or we can work this out. So we had a meeting.”

At that meeting, on March 14, after Leyba and Schmitz reiterated the archdiocese’s reasons for closing the church, Peña and DeHerrera were ready with possible solutions. They had found four retired priests who were willing to conduct Mass once a week, and Peña would pay for an additional administrative assistant to relieve the pressure on Holy Trinity. OLV had $250,000 in the bank, and was well on its way to making some much-needed capital improvements, including a new roof and a repaved parking lot. The parish was healthy and active and might skew older, but how many Catholic churches in the United States could boast a wealth of young parishioners?

Leyba and Schmitz listened, then repeated their decision: The church was closing.

Dissatisfied with their response, Peña instructed his private lawyer to write the archdiocese’s attorneys, requesting that documents related to the decision not be destroyed in case they one day needed to be reviewed in an official capacity – like in court. “They took offense to that,” says Peña.

Sandra Garcia is head of the Goat Hill Catholic Society and a longtime member of OLV.

Anthony Camera

At Mass on March 26, Father Leyba announced that there would be a meeting between the archdiocese and OLV congregants at Holy Trinity on March 29. Pierre Lopez, president of the parish council and a longtime OLV member, stood and said, “Father, we want the meeting to be here: This is our church, these are our people,” recalls Sandra Garcia, a member of OLV since 1990 and now head of the Goat Hill Catholic Society, a group that later formed to advocate for the church.

“The entire congregation stood up and said, ‘We are having the meeting here!'” Garcia says. And that they did, filling practically every seat in the room save for three chairs.

After Our Lady of Visitation’s final Mass on April 30, 2017, about sixty congregants boarded two buses for a planned protest at the archbishop’s private residence in south Denver.

DeHerrera, who was traveling with Peña in a separate car, received a call from a spokeswoman for the archdiocese; she wanted to work out a deal and avoid the impending television spectacle. Her offer: A priest would be made available to give Mass at OLV once a month.

Peña instructed the buses to park a few blocks from Aquila’s home while he, DeHerrera and other members of the Goat Hill Catholic Society discussed her offer. DeHerrera thought it was a sound compromise, but he was in the minority; the members voted down the deal.

The closest that protesters got to the archbishop that day was the gate protecting his home. Aquila’s only personal interaction with OLV remains a meeting after that protest with Lopez, when Aquila gave the parish council president a letter reiterating his decision to end Mass.

On May 1, Lopez and Peña sent a letter requesting intervention by the Vatican to the papal nuncio in Washington, D.C., the official channel between the U.S. and Rome. They have yet to receive a response.

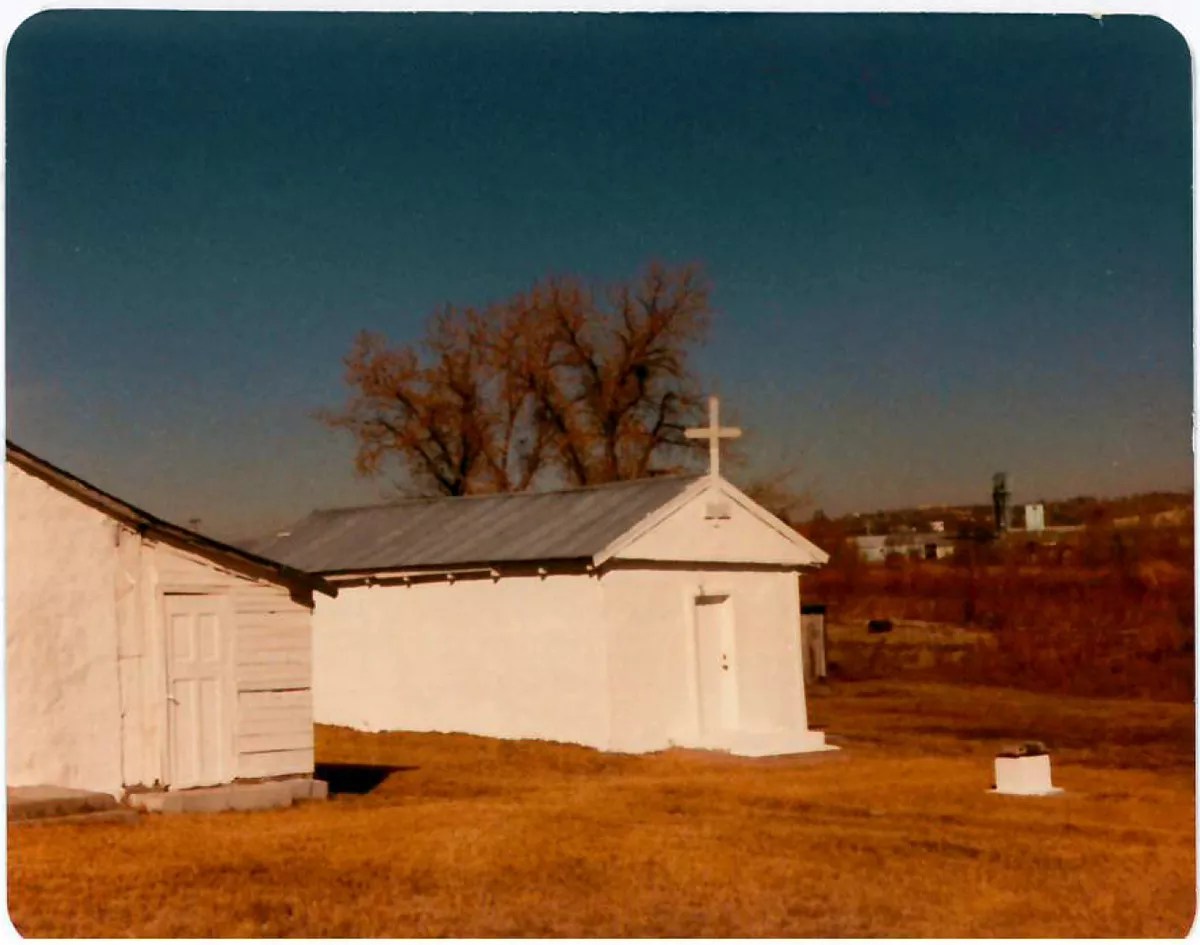

Once a bustling community and place of worship, the church now sits empty.

Anthony Camera

OLV members have their own theory about why the archdiocese closed their church.

Dotted with dilapidated homes, adult bookstores and liquor joints, the Goat Hill neighborhood – between Lowell Boulevard to the west, Pecos Street to the east, West 67th Avenue to the north and West 64th Avenue to the south – might be poor now, but it’s just a few minutes from downtown Denver, and a new light-rail station sits about a half-mile from the church. Both attributes make the property valuable. Parishioners have been repeatedly told by the archdiocese that the church won’t be sold – that in fact, the property will be used for events – but those events have yet to occur, they say.

After the archdiocese took the keys, it took control of OLV’s bank accounts. Last summer the church got a new roof that cost about $105,000, according to Adams County records; parishioners had gotten a bid for a new roof just a few months earlier that had come in at half that amount. Some members suspect the archdiocese drained OLV’s savings account so that even if parishioners were allowed to return to the church, they wouldn’t be able to sustain it for very long.

The archdiocese did not answer questions about OLV’s closure, but pointed us instead to a prepared “OLV Fact Sheet.”

Sister Kate Kuenstler is all too familiar with OLV’s plight.

When the Catholic Church’s sex-abuse cases erupted over a decade ago, United States bishops who’d come into their roles under popes John Paul II and then Benedict (Aquila’s way into the Denver archdiocese) were confronted with a sudden need to pay for civil lawyers, as well as cover fines and private settlements with victims. They turned to the “stable patrimony of the diocese, which are the church buildings,” says Kuenstler, who is helping OLV with its petition to the Vatican. The Rhode Island-based nun is one of the few canon lawyers in the U.S. who works on such cases; she is educated in the Code of Canon Law, a body of regulations that has governed the Catholic Church since the early days of Christianity.

Though there are several ways to close a Catholic church, U.S. bishops have taken the same path over the past fifteen or so years: They merge parishes, claiming one no longer needs its own campus, then relegate the empty building to secular use and ultimately sell it. The churches most often targeted are ethnic parishes that, like OLV, have a history of sustaining themselves and not relying on a diocese. The Archdiocese of Denver does not consider Our Lady of Visitation a closed parish; instead, it has “merged” with another church.

“The bishops of the United States have made a tactical decision, a strategic decision, never to use the other ways of reconfiguration – to always use merging, because they are always looking for cash that comes from the sale of the campuses,” Kuenstler says. “Merging is the only configuration where you end up with an empty church building and empty campus that you can sell.”

Kuenstler has helped 52 dioceses and 200 to 300 churches across the United States, Canada, England, Ireland and Wales over the last thirteen years, but she’s never won a merger case that made it all the way to Rome.

OLV congregants remain hopeful that theirs will be the first.

Jerry Roys was an altar boy at Our Lady of Visitation and is now an unofficial historian of the Goat Hill neighborhood.

Anthony Camera

As a kid growing up in the ’60s, Jerry Roys would rush to Sunday Mass at Our Lady of Visitation. But he wasn’t exactly eager to pray in Latin for an hour. The altar boy wanted dibs on the handful of robes that weren’t frayed at the bottom or too small. “OLV has always been a poor church,” he says.

Like many OLV parishioners, Roys has a familial connection to the church’s beginnings: His dad’s first cousin helped Benito Garcia build it.

A new wave of workers moved to Goat Hill from southern Colorado and northern New Mexico in the ’40s, lured by jobs in the fields of enterprises like Savery Savory Mushrooms. (The defunct farm’s water tower still stands near Federal Boulevard and West 110th Place in Westminster.) A priest would go around the working-class neighborhood, offering Mass in people’s homes.

In the late ’40s, that priest and Garcia asked the Denver Tramway Company, which was about to reach the end of the line thanks to the automobile, if it would consider donating a streetcar that they could use to build a church. After the company agreed, a neighborhood farmer sold his prize-winning hog to fund a raffle that raised money for a second streetcar. In 1950, Garcia donated a parcel of land in the North Lawn Gardens subdivision of Goat Hill to the archbishop for the creation of a church at 2351 West 65th Place.

Propping the streetcars on cinder blocks, Garcia and other men from the community gutted and merged them, then brought in a cauldron to serve as a heater and erected a wooden cross. And just like that, Our Lady of Visitation was born.

Roys’s father, a Trinidad coal miner, moved his family to Denver in 1961 after his mine closed. They lived in Congress Park before relocating to Goat Hill.

The morada down the street from OLV stands as one of the few in the U.S.

Courtesy of Sandra Garcia

Roys’s parents practiced different kinds of Catholicism. His father was a penitente, a member of a religious group indigenous to northern New Mexico and southern Colorado whose origins can be traced to fifteenth-century Spanish Catholicism. Legendary for their dramatic displays of penance, including self-flagellation, penitentes have morphed into more of a brotherhood that helps impoverished Latino communities in secular and non-secular ways. The shift from devout religious order to social group happened after Mexico won its independence in 1821 and Spain withdrew its priests, leaving many communities in what’s now the southwestern United States without spiritual leaders – or any leaders at all. The penitentes filled in. Roys says his father never went to church with his family, but he can remember him praying every day and visiting the morada, a gathering space for penitentes that today stands just down the street from the empty OLV building.

Roys never asked his father why he didn’t attend church. But history offers some clues.

Up until the late ’40s, many Catholic churches were segregated. White congregants were allowed to sit in the main pews, and congregants of color were relegated to the balconies. (It wasn’t just a church practice: Signs on restaurants around Colorado and across the U.S. discouraged “Hispanics and dogs” alike from entering.) The Catholic Church’s stance regarding Hispanics and other racial and ethnic communities gave rise to ethnic parishes such as Our Lady of Visitation.

Roys remembers his mother as a devout Roman Catholic, so old-school that she wouldn’t let the family eat breakfast on Sunday before they took communion. That didn’t stop Roys and his friends from drinking the sacramental wine before Mass, though. “You’d get all buzzed out,” he recalls. “Boy, my mom gave me a whooping one Sunday because she could tell.”

Our Lady of Visitation was a welcoming place for Hispanics in a metro area that was very much segregated, and offered a respite from the violence and poverty that started strangling north Denver in the ’60s.

By the time Roys was fourteen, he knew three or four guys on his block who were dealing dope. “I always say I grew up on a block with almost eighty kids, and about a quarter of them ended up doing some kind of time, including me and my youngest brother,” he recalls. “But there were also the guys who became professors and doctors. There were a lot of hard workers.”

When Roys was in grade school, local farmers would come to Goat Hill at the end of the school year to recruit kids to work their land. Roys started working the fields when he was about nine. “That’s what you did every summer until you went into the Army or you graduated and got a job doing your dad’s work,” he says. “The reason we worked in the fields is because they weren’t going to hire us to work at McDonald’s or some place like that. We weren’t going to get that job.”

Jerry Roys, second from right, on the day of his First Communion.

Courtesy of Jerry Roys

One summer, Roys was working at a field near West 52nd Avenue and Wadsworth Boulevard in Arvada. He and his friends would usually get a ride back to Goat Hill from the farm, but one day their ride never showed and they had to walk home. “On the way back, cops stopped us and wanted to know what we were doing, where we were going, where we were coming from,” he remembers. “It’s like, get back to your side of the tracks; you know where your place is.”

That place is complicated, full of culture and community but lacking in infrastructure and adequate schools. Up until about 2009, Goat Hill didn’t have any sidewalks. To this day, some of the more residential areas, including the street where OLV is located, still don’t. Roys recalls teachers at his elementary school mocking students who would track mud inside. “They didn’t have anywhere to walk,” he says. He can easily name at least five guys from the neighborhood who were hit by cars – including his brother, who was hit by a car in Goat Hill.

Roys went to college for journalism but now works with his hands. Like his father, he can do it all: roofing, pouring concrete, construction. About seven years ago, Roys started working on a documentary about how difficult it was for children in the neighborhood to get to school. He showed Adams County officials a photo of a child walking to school in the snow; the kid wasn’t much taller than the fender of a car. He was told to form a committee that could look into the issue.

Roys stopped attending Our Lady of Visitation years ago and says he no longer subscribes to a specific religion but instead refers to himself as “spiritual.” He still keeps up with OLV and its congregants, many of whom he’s known his entire life. And until OLV closed last year, Roys was a faithful attendee of the church’s annual bazaar.

The fundraiser drew thousands of people from the community and beyond, shutting down the block around OLV for three days every July. Hundreds of volunteers manned booths, organized horseshoe tournaments and hosted bingo games. Bands played for free.

More than a way for OLV to bolster its coffers, the bazaar was a celebration of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, a region infused with the cultural remnants of Spanish colonialism, northern Mexican heritage and such American values as striving for a better life than your parents had. People who can trace their lineage to the small towns that dot this region are adamant about how they describe themselves. They are either Chicano, Hispanic, Spanish-American, Mexican-American or just straight-up American. Each descriptor carries its own history and turmoil. Many don’t speak Spanish; in the ’50s and ’60s, second-generation Mexicans often got in trouble for speaking their parents’ native tongue in school, which kept them from passing it on to their kids. If they were living in Denver at that time, they remember how the Anglo kids in school would gawk at their lunches of tortillas and beans. The irony of Mexican food’s popularity in the U.S. these days isn’t lost on them.

Almost anyone you ask in the neighborhood will tell you that the bazaar had the best, most authentic Mexican food around: pots of beans, tamales, green and red chile, tortillas handmade by the abuelitas of Goat Hill. That’s why congregants like to say that OLV was built “one tortilla at a time.”

OLV founder Benito Garcia and his wife, Eloisa, celebrating their fiftieth wedding anniversary.

Courtesy of Sandra Garcia

Although Roys hasn’t been involved directly with OLV for years, its closure still feels personal. “The archdiocese has taken away their opportunity to serve God,” he says.

Sister Kate Kuenstler doesn’t view the archdiocese’s decision regarding OLV in religious terms, she says, because the bishops with whom she has dealt don’t. Their decision to merge parishes is strictly business; churches are registered corporations, their archbishops the presidents and CEOs.

“We’re not dealing with theology of beliefs or the sacramental life of the community,” she explains. “We’re talking about what is a corporation only. [Parishioners] see themselves as a community of believers who gather on a Sunday and form a system of care and concern and belief. None of that, none of that, none of that is considered by the bishop. If he did, there would not be this trauma right now within the parish.”

Archbishops must follow a procedure to merge parishes. First they must issue a decree stating that the merger will happen. Parishioners can appeal that decision; however, the judge is the bishop himself, meaning the decree’s creator can reject its appeal.

If an appeal is rejected, parishioners have the option of requesting a review by a body of Vatican officials who work under the Pope. The process can take anywhere from two to five years, during which time the church sits in a sort of purgatory, unable to be used by parishioners or sold.

An archbishop must provide a “very grave” reason for unconsecrating a church, such as the building being no longer fit for use. That’s why Kuenstler advises her clients to secure a report on the quality of the church building and an assessment of the property’s worth “so we know what the bishop is looking at.”

“None of that, none of that, none of that is considered by the bishop. If he did, there would not be this trauma right now within the parish.”

According to Adams County, OLV’s land and buildings – a brick-and-mortar church replaced the streetcars decades ago – are worth $455,892. However, that figure doesn’t take into consideration factors that could potentially add value to the property, such as the nearby light-rail station or recent improvements to the buildings.

Should the Vatican rule against them, OLV parishioners have hinted that they will take the case to civil court. But few American judges are willing to wade into canonical territory, according to Terry Kelly, a Denver lawyer assisting OLV. “It’s very awkward as an American lawyer and American civil lawyer to try to understand and explain canon law that is applicable here,” Kelly says.

The governing body that enforces the Code of Canon Law, the Catholic Church, is ruled by the Pope. He resides in the Vatican, an independent state in Rome, and his powers are both practical and mystical. As far as Catholics are concerned, he is God’s representative on Earth, interpreter of all dogma. But he and his government can also change rules, such as how Mass is delivered. Under the Pope are cardinals, who serve in countries around the world, and under them are the various levels of bishops, priests and deacons, who serve in dioceses.

Although they take their orders directly from the Vatican, archbishops bring their own political and social leanings to their dioceses.

Aquila is widely seen as a conservative whose primary concern is abortion, which he regularly portrays as the gravest threat to society in his column on denvercatholic.org. He was the first Denver archbiship to observe the National Day of Remembrance for Aborted Children, in September 2016. In a column published a month later, he implied that voters in that year’s presidential election should consider Donald Trump because the Republican Party supports the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits federal funding for abortion. “Catholic voters must make themselves aware of where the parties stand on these essential issues,” Aquila wrote. “The right to life is the most important and fundamental right, since life is necessary for any of the other rights to matter.”

But Aquila was also asking the Denver diocese’s estimated 550,000 Catholics – more than 50 percent of whom are Latino – to consider voting for an isolationist candidate who’d called Mexican immigrants rapists. In 2017, Aquila urged the diocese to support children brought into the U.S. under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, but also indicated in his letter that the diocese would sever ties with any DACA employees should the program be rescinded.

Some OLV congregants argue that Aquila’s political advice and his stance on DREAMers indicate that he does not consider the priorities of the majority of his followers. To them, that’s more evidence that Aquila is not weighing the cultural significance of Our Lady of Visitation in the working-class Latino community that it serves.

Adding salt to the wound is a $6.5 million private residence that Aquila built for himself and other diocesan leaders in 2014. The archdiocese maintains that the residence was built with private donations and also serves as a community center. “I’ve never heard of any events happening there,” Peña says.

Churches are owned by archbishops and must pay dues to the archdiocese, even if they are self-sustaining. That’s a system that very few American courts will challenge because of the constitutional separation of church and state. “I think the canon law powers, for the archdiocese and for pastors, is basically a medieval monarchy, meaning the king can do no wrong and the king can do whatever the hell he wants to do,” Kelly says.

Still, Kelly thinks OLV has a fighting chance to prevail in civil court. “The property is deeded from Benito Garcia to the archbishop of Denver for the benefit of Our Lady of Visitation,” he points out. “Whether the parish could prevail by saying that their trustee, the archbishop, should be removed as the trustee for not operating the property for the benefit of Our Lady of Visitation is what the legal question, I think, should be.”

But the challenge would prove lengthy and expensive. “Let’s put it this way,” Kelly continues. “We’re working as hard as we can to avoid that and doing whatever we can, in every other form, to avoid that sort of confrontation.”

Kuenstler acknowledges the challenges ahead for OLV, even though the Vatican is ruled by a pope whom many consider a man of the people. But friendly and approachable as he may seem, Francis is still presiding over an ancient, complex institution whose membership is in the billions.

“Winning isn’t everything,” Kuenstler says. “The reason I take on cases that have quality stories, quality evidence, is to report to Rome what the bishop is doing so the Vatican can pay attention to a bishop that is abusing his people. We tell the Vatican the truth. If I did this to win, I’d have ended twelve years ago.”

Children receiving their First Communion at Our Lady of Visitation in the 1950s.

Courtesy of Sandra Garcia

When Federico Peña moved to Denver in 1973, the late Chicano political activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales was in his prime. “There were all these political movements of Latinos fighting society, fighting police, fighting courts, fighting government,” Peña says. “There was a sense of discrimination in the broader community.”

Peña’s own mayoral election was a rebuff to the good ol’ boy network that then dominated Denver politics. Four years after being elected to the General Assembly in 1979, he defeated incumbent Williams McNichols Jr. to become the first Latino mayor of Denver. After his second term, he was selected by President Bill Clinton to lead the Department of Transportation, then the Department of Energy.

Unlike many OLV parishioners, who can trace their roots to the same small towns in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, Peña grew up in south Texas. He came to know OLV through his father-in-law, Lloyd Quintana, a thirty-year member and deacon.

Peña didn’t join OLV just to score points with his wife’s father, though. He found Our Lady of Visitation’s austerity and tight-knit community a respite from other Catholic churches he’d attended in Denver. The “little church,” as it’s known in Goat Hill, had room for no more than a hundred parishioners and was regularly packed. Mass was said in English, but the hymnals were sung in Spanish and accompanied by soft guitar music. Instead of rushing home when Mass ended, parishioners stuck around to catch up with each other, snacking on doughnuts and coffee. Photos of servicemen and -women who’d grown up in the church lined the walls.

That’s all on hold now. While former OLV parishioners wait to hear if the Vatican will side with them, a few have joined Holy Trinity. Others are hopping around various parishes in town, trying to find a new spiritual home.

Our Lady of Visitation sent surveys to 130 parishioners gauging their involvement in religious life after the church had closed; about 100 responded. Fifty-nine respondents said they were attending mass on a regular basis, though only eight were going to Holy Trinity. Fifty-seven reported that they were attending mass less frequently, and forty said their pastoral needs were not being met. Comments attached to the survey reflect respondents’ difficulties in finding a new parish and their growing sense of distrust of the Catholic Church as a whole: “Not interested in the Catholic Church.” “Do not trust archdiocese and leadership.” “Have not found church where I feel comfortable.” “Catholics betrayed us in our trust.”

Peña hasn’t returned to a Catholic church since OLV closed.

He says that OLV’s members see their current struggle as another fight to preserve their culture in a country that has yet to fully embrace them. “That’s the history here,” he says. “The archbishop doesn’t understand that, apparently. He doesn’t understand that he’s dealing with a very sensitive historical cultural community that feels very deeply about its roots.”