Audio By Carbonatix

The Colorado Civil Rights Commission has been slapped around plenty the past few years, mainly for ideological reasons. But a new report from Colorado auditor Dianne Ray chastises the panel for a multitude of other sins, including poor performance, a lack of transparency and general incompetence.

These assertions are certainly disturbing from a management perspective. But the study also shows that despite Colorado’s reputation as a progressive state where employees and citizens in general are treated fairly, nearly 7,000 people in the state formally complained about being the victim of discrimination, bias or the like between November 2016 and June 2019, the analysis period.

Not all of these claims progressed through the system, and the auditor’s office wasn’t able to assess each of the almost 1,300 that did – because data was incomplete for more than a quarter of them.

The commission, which operates under the auspices of the Colorado Civil Rights Division, is described on its website as “a seven-member, bipartisan board whose mission is to conduct hearings regarding illegal discriminatory practices; advise the Governor and General Assembly regarding policies and legislation that address illegal discrimination; review appeals of cases investigated and dismissed by CCRD; [and] adopt and amend rules and regulations to be followed in enforcement of Colorado’s statutes prohibiting discrimination.”

Still, the agency’s most prominent action this decade has involved Lakewood’s Masterpiece Cakeshop. In 2012, the bakery’s owner, Jack Phillips, refused to make a wedding cake for Charlie Craig and Dave Mullins, a gay couple, citing his religious beliefs. In May 2014, the commission ruled that Phillips was guilty of discrimination, setting into motion a long ramble through the judicial system that seemed to have ended in June 2018, when the U.S. Supreme Court sided with Phillips in a ruling that specifically took the commission to task.

The board fell short when it came to “the State’s obligation of religious neutrality” in considering Phillips’s actions, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in his majority opinion, which cited this comment from an unnamed member of that commission: “I would also like to reiterate what we said in the hearing or the last meeting. Freedom of religion and religion has been used to justify all kinds of discrimination throughout history, whether it be slavery, whether it be the holocaust, whether it be – I mean, we – we can list hundreds of situations where freedom of religion has been used to justify discrimination. And to me it is one of the most despicable pieces of rhetoric that people can use to – to use their religion to hurt others.”

Jack Phillips and his granddaughter at Masterpiece Cakeshop in Lakewood.

The beef between the commission and Phillips didn’t end there, however. The board opened up a new investigation of the baker after a complaint that he’d declined to bake a cake to celebrate a patron’s gender transition, prompting a lawsuit accusing the state of de facto harassment in the wake of the Supreme Court decision. The two sides didn’t agree to make peace until March of this year.

That’s not all. In February 2018, long before this resolution, Republicans in the state legislature opened up another line of attack by putting forward an appropriations proposal that would have defunded the commission. Ultimately that didn’t happen, but the agency was splattered with mud for months, with GOP reps arguing that it needed to be restructured.

Now there’s more blood in the water, thanks to the auditor’s report. Here are its key findings, which name-check both the commission and the Colorado Civil Rights Division.

• The Division did not complete its investigative work for 367 of the 933 complaints we reviewed (39 percent) within 270 days, as required by statute. On average, the Division took almost a year to complete its work on each of these delayed cases.

• The Division could not provide evidence that staff were actively investigating complaints for time spans ranging from 3 to 10 months for nine of a sample of 25 complaints.

• The Division’s records show the Division initiated time extension requests to complete its own work in 58 of a sample of 66 such requests we reviewed, when statute only provides for the complainant and respondent parties to request time extensions. The Commission approved all of the requests, which extended the 270-day statutory deadline, but could not provide evidence that it considered whether there was “good cause” to grant the extension, as statute requires.

• The Division did not maintain complaint information that was accessible in any aggregated form to support its decision-making, achievement of objectives, or external reporting, from November 2016, when it implemented its online complaint management system, through the end of our audit period (June 2019).

• The Commission does not operate in a manner that allows for transparency or accountability. It could not provide evidence in meeting minutes or audio recordings that it discussed the cases, applied rules and policies to the reviews, and how it decided the disposition of any of the 218 cases it reviewed in Fiscal Years 2017 and 2018. Further, the Commission votes in executive session, in violation of the Colorado Sunshine Law.

Many of the specifics are even more problematic. The report found Excel spreadsheets showing that 1,292 cases were filed and closed during the audit period, but complete data could be found for only 933 of them. For this reason, the auditor’s office was unable to review 359 cases that presumably existed at one point but left behind only traces.

The aforementioned sample of 25 complaints revealed more examples of justice either delayed or denied. In two cases, the division waited between four and five months after receiving initial information from the target of the complaint to so much as ask the original filer for a rebuttal. In another, there was an eight-month lag between receiving the rebuttal and contacting the complainant to continue the investigation. And in four cases, the office found no evidence of further inquiry after getting the rebuttal.

Granted, the number of complaints with which the commission must deal is astonishing. As you can see in the chart above, the number of those alleging wrongdoing in employment, housing or public accommodation, the three main categories the panel addresses, went from just under 1,000 in 2015 and 2016 to well over it during subsequent years.

Just as troubling, the 2019 total of 1,929 complaints is higher than in any previous year even though the digits only cover the first six months.

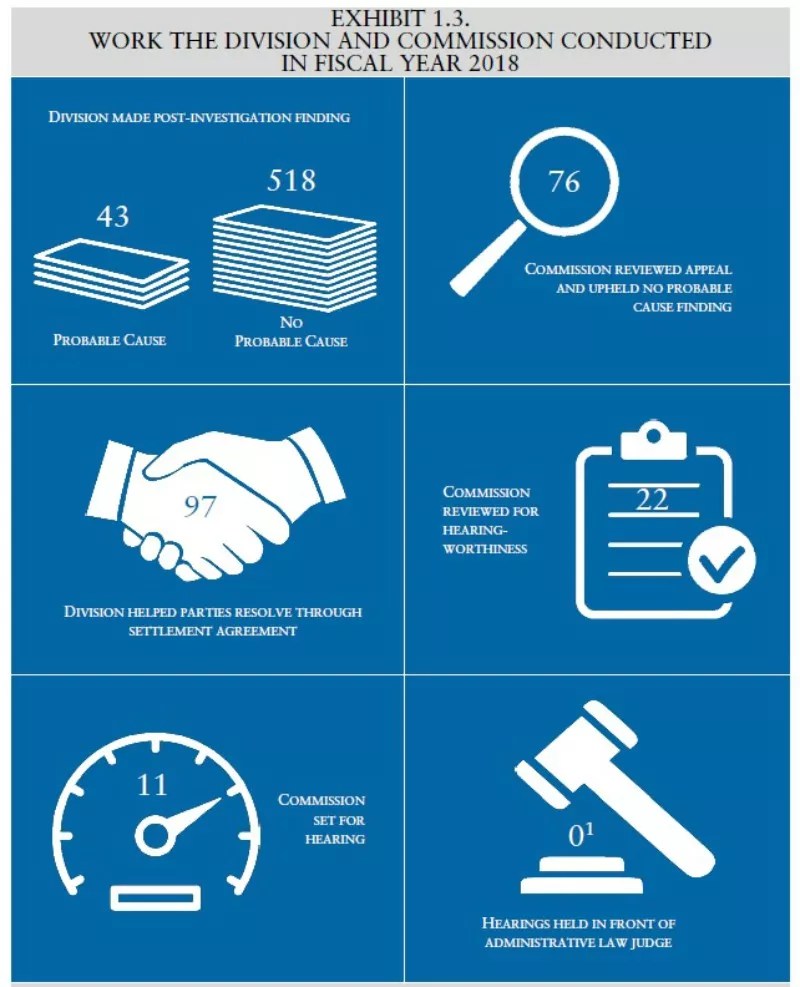

Complaints don’t always make it all the way through the process. Another graphic contained in the report breaks down the commission’s work in fiscal year 2018. Over that span, 1,693 complains were filed, but only 518 – fewer than a third – reached the post-investigation-finding stage. Moreover, 43 cases, or fewer than 10 percent, were found to have probable cause.

Appeals were filed in 76 instances when no probable cause was found, and on 97 occasions, the division participated in settlement agreements between the parties. But just 22 of the cases were reviewed to determine if they were worthy of a hearing, and only half of them won approval. Because all eleven of the latter were settled before a hearing could take place, not one of the controversies was heard before an administrative judge.

The following graphic, which encompasses the excerpt at the top of this post, lays out the particulars.

The auditor’s office put forward six recommendations for improvement, and not only shared them with the Colorado Civil Rights Division, but included the latter’s responses. The division agreed without reservation to three of them – plans to improve timeliness, upgrade its online CaseConnect filing system, and study the resulting data to figure out how best to address discrimination. These changes are supposed to be implemented by January 2020.

In the other three cases, the division equivocates by maintaining that it “partially” agrees with the recommendation. For example, the auditor’s office suggests that the commission should prohibit the division from initiating requests for time extensions, ask that extension requests actually give a reason why they’re needed and create a process by which the requests will be judged. The division pushes back, saying that it hasn’t been initiating the requests, putting the blame on the other parties.

In response, the auditor’s office points out that it found 88 percent of sample requests were initiated by the division. “This practice does not appear compliant with statutory intent or a plain reading of the law,” the report states.

An even more fundamental disagreement is centered on the office’s recommendation that the commission “should operate in a transparent and accountable manner” by “documenting the consideration of each appeal and hearing-worthiness case that demonstrates the application of the factors in rules and policies; discussing the factors in rules and policies, and commissioners’ perspectives on how these factors should be applied to each appeal and hearing-worthiness case, and use the discussion as a basis for decision-making; [and] voting on appeals and hearing-worthiness cases during open meetings, in accordance with statute.”

The response? “Because the commission functions in both a quasi-judicial and quasi-prosecutorial roles, the commission’s confidential discussions are not subject to documentation. The commission will not engage in creating a record of its deliberations.”

To get more details, click to read Colorado Auditor’s Report: Colorado Civil Rights Commission Management of Civil Rights Discrimination Complaints.