Kurgu128/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

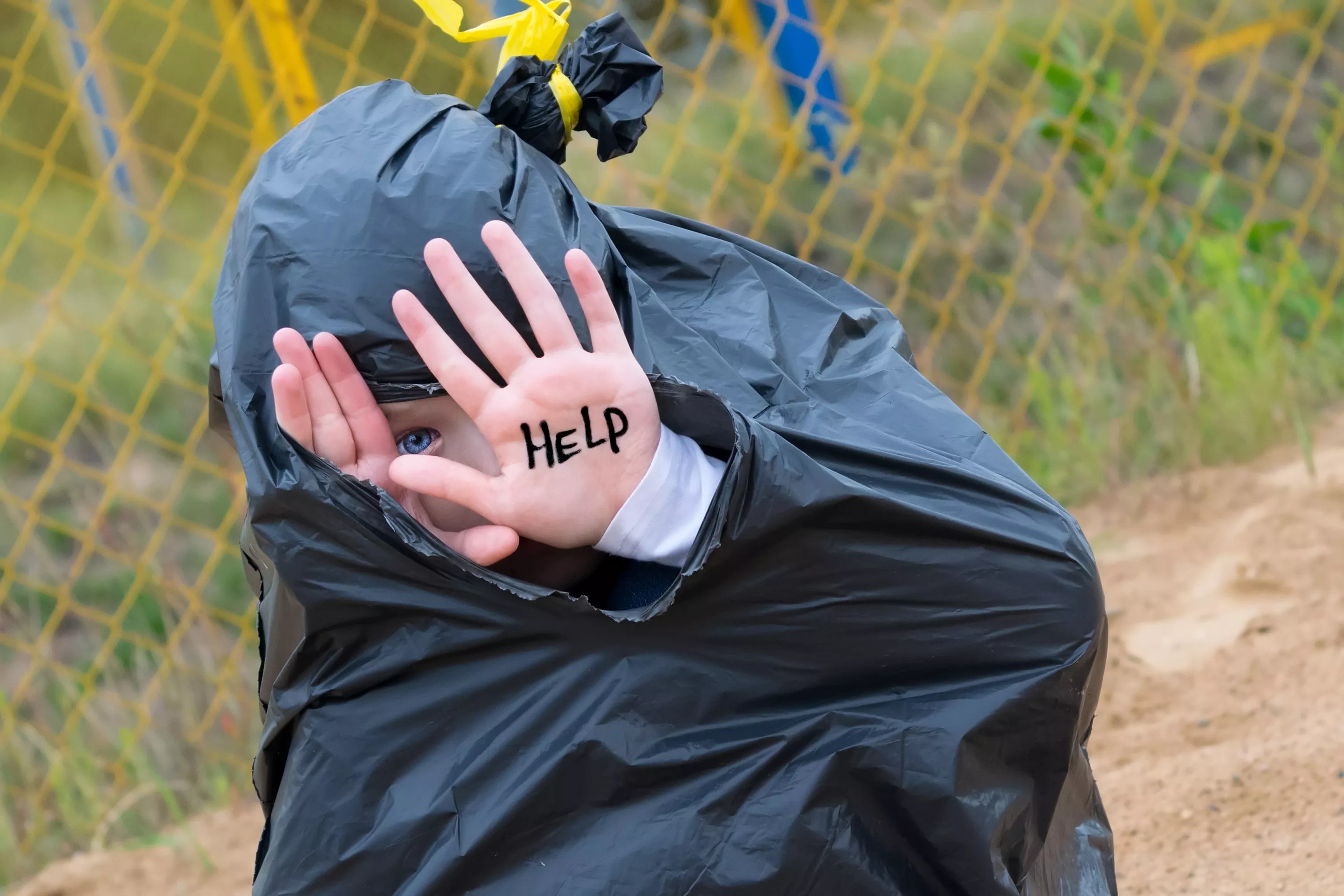

Colorado could soon overhaul its mandatory reporting law – and change its definition of child abuse and neglect.

The state’s mandatory reporting law, adopted in 1963, was the first of its kind in the nation, and though it has been amended 31 times, those changes have primarily added the types of professionals who must report rather than addressing how to make reports more accurate. In 2021, the state’s Child Protection Ombudsman released a brief detailing the lack of infrastructure for quality reporting in the state; the next year, the Colorado Abuse and Neglect hotline received over 200,000 reports, overwhelming the system.

In 2022, the Colorado Legislature established the Mandatory Reporting Task Force to examine the system; it released an interim report this month ahead of the 2025 deadline to deliver its final recommendations. In that report, the group explains why it decided that addressing the definition of abuse and neglect is the first step to improving mandatory reporting.

“The Task Force has routinely identified that Colorado’s current definition of abuse and neglect is too broad and conflates several circumstances – such as poverty – with child abuse,” the report says. “Without first addressing the definition of abuse and neglect, the Task Force cannot meaningfully recommend changes to the current mandatory reporting system or law.”

The group comprises 34 members ranging from those who have been impacted by mandatory reporting laws to professionals involved with mandatory reporting; it is chaired by Child Protection Ombudsman Stephanie Villafuerte.

Although members of the task force may have differing opinions, Villafuerte says each perspective has been valuable. And regardless of their differences, they all agree on one thing.

“There is agreement, no matter what, that Colorado’s mandatory reporting law is not working as effectively as it should,” Villafuerte says. “There’s nobody on the task force who’s like, ‘This is great. It works fine. Don’t touch it.'”

Nearly forty professions are included in Colorado’s mandatory reporting law. In its 2021 issue brief, the CPO argued that mandatory reporters know too little about their responsibilities.

“Studies show that more child abuse reports do not necessarily result in a greater number of substantiated child abuse cases and that untrained reporters can contribute to an overabundance of unsubstantiated reports – draining child welfare systems of much needed resources,” the brief said.

Additionally, there is growing evidence that mandatory reporting laws disproportionately affect families of color, low-income families and those with disabilities. In Colorado, for example, Black children are reported to the abuse hotline 1.27 times more than their percentage of the state’s population, according to data presented to the task force by Casey Family Programs.

According to Villafuerte, the task force also studied other states’ exclusions that stipulate poverty or homelessness alone are not a basis for child abuse reports.

“We, right now, under the law, are conflating poverty with child abuse,” Villafuerte says. “We’re saying that if a family doesn’t have housing or if a family doesn’t have adequate food that that child is in danger – not necessarily in danger of physical or sexual abuse, for example, but do they need resources? Yes.”

The only current mechanism for reporting that children are at risk and need resources, however, is through the child abuse and neglect hotline, which inevitably engages families with Child Protection Services who might not require that attention.

“I would say that that is the single greatest balancing act of the task force, is trying to figure that out,” Villafuerte says.

Another item that the task force plans to address is whether those who work with victims of domestic violence should be mandatory reporters. Currently, those advocates are required to report child abuse because the child is in an unsafe household or may need resources.

“What advocates are arguing is that having to be mandated reporters really puts them at odds with their client,” Villafuerte says. “They’re supposed to be taking sensitive information to help the family, and in the same breath, we’re requiring them to turn that information over potentially to the child abuse hotline.”

That can cause parents being abused to not report their abuse because they are worried they will be viewed as a bad parent or lose their child in the process. The task force plans to examine such situations more before it issues its final recommendations in 2025.

It will also work to clarify other vagueness in the mandatory reporting law, such as what it means to “immediately” report suspected child abuse. “Immediately” is currently not defined in Colorado. Additionally, it will consider what required mandatory reporting training should look like. There is no such requirement right now.

Training could include information about implicit biases, as well as the basics of when to report and why, in an attempt to combat overreporting of certain groups.

According to Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, Colorado’s task force has “done a better job than any other group” just by observing that such laws should be narrower, but Wexler still hopes the task force will go further in its last year and with its final recommendations.

“The Colorado commission said, ‘Before we recommend anything on who’s supposed to report and whether we want to change that, first we’re going to recommend how to narrow the law,'” Wexler says. “By the standards of what’s been done in child welfare for fifty years, it’s revolutionary. Now, it’s also not nearly enough.”

Wexler’s group argues that mandatory reporting should no longer exist – but according to Villafuerte, that’s not something the Colorado task force has contemplated. Still, Wexler says the potential for the task force to exempt domestic violence counselors and create other means of reporting when a child needs assistance beyond the child abuse hotline would be positive steps.

The task force has until January 1, 2025, to make its formal recommendations to the legislature.

“The next eleven months, we’ll be busy,” Villafuerte says.