Jacob Curtis

Audio By Carbonatix

Despite a slew of completed and ongoing clinical trials demonstrating the efficacy of psilocybin mushrooms in treating certain medical conditions, and being labeled a “breakthrough therapy” by the Food and Drug Administration, the primary compound in psychedelic mushrooms remains a Schedule I substance under the federal Controlled Substances Act.

Schedule I is the highest of the five tiers defined in the CSA. It’s a group of drugs that have no currently accepted medical uses, but a high potential for abuse – according to the federal government, anyway. (Marijuana also remains a Schedule I drug, despite forty states currently allowing residents to use medical marijuana.)

But a move by the Drug Enforcement Administration earlier this week could lead to psilocybin being rescheduled to Schedule II, which would open up its use under federal and state “Right to Try” laws for terminally ill patients. Colorado was the first state to pass a Right to Try law in 2014, with others soon following. In 2018, the federal government enacted the legislation, too, allowing terminally ill patients to “access investigational treatments that have passed basic safety testing (Phase I) with the FDA but are not yet available on pharmacy shelves.”

On Monday, August 18, a Law360 report detailed emails wherein the DEA sent a petition to move psilocybin from Schedule I to Schedule II to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The petitioner, Seattle physician Dr. Sunil Aggarwal, initially asked the DEA to drop psilocybin a level in February 2022. He was looking for a legal avenue to treat terminally ill patients with psilocybin, but the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against using psilocybin under Right to Try at time because it was a Schedule I substance.

But Aggarwal’s current attempt at rescheduling may be more successful. According to Vicente LLP founding partner Joshua Kappel, a cannabis and psychedelics attorney, the petition could find a more willing ear in the current HHS administration.

“In layman’s terms, the DEA transferring the petition to HHS really starts the process, and allows HHS to apply what they believe would be the right schedule as well,” says Kappel, who helped write the proposition that legalized medical psilocybin use and decriminalized a handful of natural psychedelics in Colorado.

A handful of promising psilocybin studies and trials are underway in Colorado, including one at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus where end-of-life patients take psilocybin as a palliative care treatment. In 2022, research at Johns Hopkins University determined that psilocybin could serve as a “substantial antidepressant” when paired with supportive therapy. Psychedelics such as psilocybin and MDMA have shown promise in treating post-traumatic stress disorder as well, with both drugs becoming increasingly popular among military veterans.

Kappel says HHS, headed by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., could suggest that psilocybin be rescheduled as Schedule III, meaning it has a moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence. The HHS secretary has vocally supported the use of psychedelics for depression and trauma.

Colorado’s Psilocybin Laws

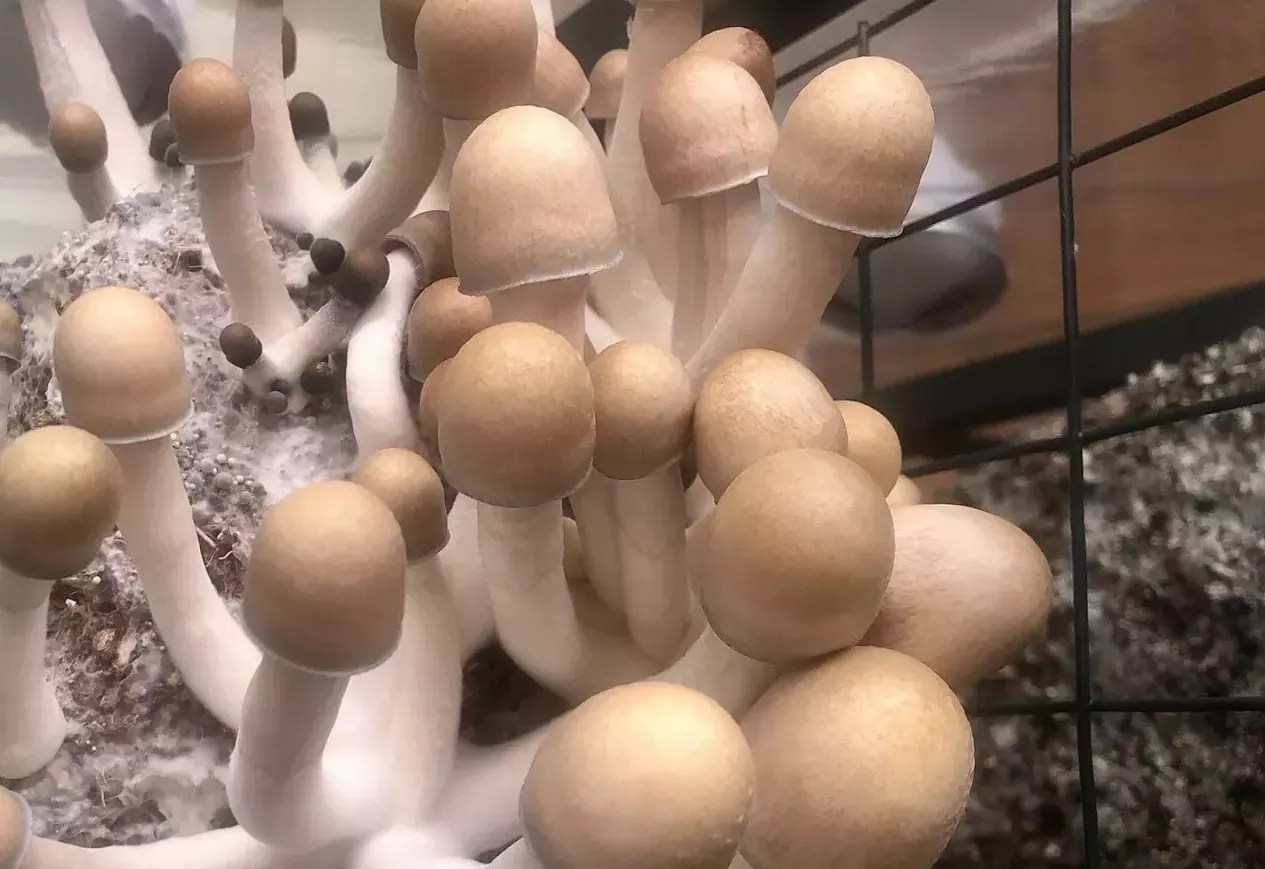

Colorado’s therapeutic psilocybin landscape, legalized by voters in 2022, is still getting off the ground after regulations and guidelines were written, with the first testing lab opening earlier this summer. A handful of licensed facilitators and cultivations have popped up across the state since.

If psilocybin shifts to Schedule II, which contains prescription drugs like opioids as well as cocaine and other stimulants, Colorado’s existing natural medicine framework would go largely unaffected, although it could face more federal oversight. However, a move to Schedule III could provide tax relief to businesses in the legitimate natural medicine field, Kappel says.

State-legal marijuana and psilocybin businesses are hamstrung by a part of the federal tax code known as 280e, a policy exception codified in 1982 to stop drug traffickers from writing off cash expenses on their taxes. Cultivators, labs, and healing centers could potentially get to write off their expenses under Schedule III, which they cannot do now.

A bump down two levels seems like an awful big wish for proponents of psilocybin treatment, but Kappel notes that Kennedy, whose views on traditional medicine are hardly traditional, presents a “non-zero” possibility as HHS secretary.

In the meantime, HHS will examine the rescheduling using the eight factors proscribed by law before making any determinations. But even a jump down to Schedule II would “really change the calculation under various Right to Try laws,” Kappel says.