VISIT DENVER via YouTube

Audio By Carbonatix

This is the first in a series about changes in gentrifying Denver neighborhoods.

Many parts of Denver have transformed over the course of the past decade or so – and none more than Five Points.

For much of the last century, the largely African-American populace of the north Denver neighborhood contributed mightily to the culture of the Mile High City even as many residents struggled to make ends meet in the face of historically discriminatory roadblocks that limited their opportunities. But new data illustrates how gentrification has shaken up the status quo, leading to an influx of young, moneyed residents and the departure of folks who simply can’t afford to stay in the only homes they’ve ever known anymore.

The information was culled from the Child Opportunity Index 2.0, a mammoth database unveiled in January by Brandeis University in Massachusetts. The project examines the 100 largest metro areas in the United States, including Denver, at a granular level, neighborhood by neighborhood, to reveal the sort of inequality set before many young people, particularly children of color, and it served as the foundation of our recent post headlined “Study: White Children in Denver Have Huge Edge Over Hispanic, Black Kids.”

At our request, a team headed by Clemens Noelke, research director for the Institute of Child, Youth and Family Policy for Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management, pulled together facts and figures for a number of Denver neighborhoods, including Five Points, by drawing from three U.S. Census tracts it encompasses.

The main sources are American Community Surveys that the U.S. Census Bureau pegs to the years 2010 and 2015, although they actually cover wider periods: 2008-2012 and 2013-2017. As such, they show what led to the conditions and scenarios being experienced by Five Points’ citizenry today.

The Child Opportunity Index 2.0 collected data on 72,000 census tracts nationwide, in association with 29 indicators. Each factor is weighted according to how strongly it predicts health and economic outcomes, with the results combined to create a single opportunity score between 1 and 100. The bottom of the scale represents the 1 percent of kids who live in neighborhoods with the lowest opportunity scores, while 100 designates the neighborhoods offering children the best odds of reaching their full potential.

Five Points’s overall numbers improved between the 2010 and 2015 reports as measured against the national average and the one for Denver specifically – from 38.1 to 45.6 for the former and 24.1 to 30.2 for the latter. But that’s only the start of the revelations in several broad categories, as outlined below.

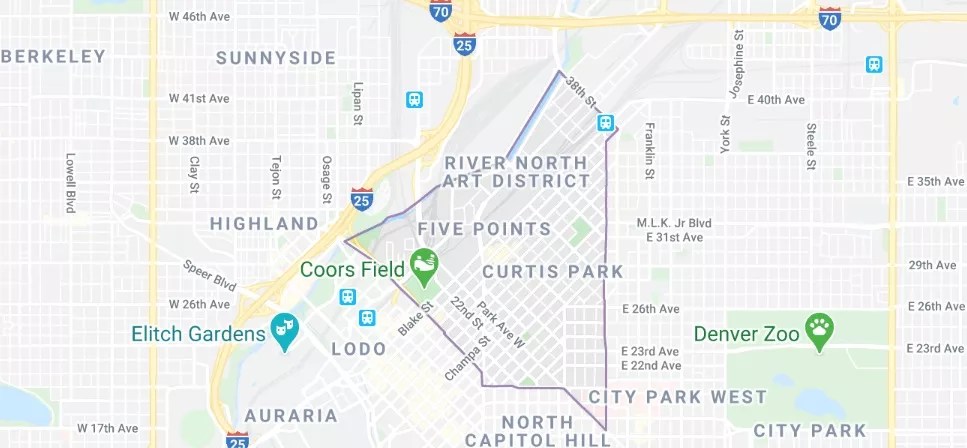

A map of the Five Points neighborhood.

Google Maps

Demographics

The number of children living in Five Points didn’t change much from 2010 to 2015, going from 1,575 to 1,592 – an extra seventeen kids under age eighteen. But the racial mix went through plenty of alterations, some minor and others profound.

The number of non-Hispanic white children fell by a modest amount, from 355 to 304, while increases were recorded in those deemed “not non-Hispanic white” (1,220 to 1,288) and children designated as Hispanic or Latino (537 to 643). But the real explosion involved children classified as “some other race or two or more races,” with the population jumping from 280 to 613.

In contrast, the total number of black children was more than halved – 601 to 287. This figure exemplifies the process by which this traditionally African-American neighborhood has transitioned, as many longtime residents and their children have moved on.

Economics

Were low-income folks who’d lived in Five Points for generations pushed out due to financial factors? Noelke cautions not to automatically make this assumption, noting that “without further information, it is not clear what is driving this change.” But the data certainly offers some intriguing hints.

Some statistics that may seem on the surface to be outliers really aren’t. For instance, home ownership rates fell from 36.2 percent in the 2010 survey to 27.8 percent in the 2015 version, and single-headed households went from 49.3 percent to 54.7 percent during that period. However, these figures are likely explained by families leaving Five Points and many of the newcomers being young and single and opting to rent places in apartment complexes that began popping up in the area during the development boom of the past decade, rather than buying existing residences.

Other categories underscore the shift to higher-income residents: median household income up ($59,082 to $65,538), high-skill employment up (53.8 percent to 59.0 percent), employment rate up (79.8 percent to 83.1 percent), and health-insurance coverage up (84.1 percent to 89.9 percent). Meanwhile, declines were registered in the public-assistance rate (14.9 percent to 13.7 percent) and the poverty rate (27.2 percent to 21.1 percent). In all likelihood, these trends have only accelerated during recent years, making it harder and harder for many longstanding Five Pointers to afford to stay in the neighborhood.

Education

By nearly every metric, children in Five Points did better toward the end of the decade than at the beginning. But this likely speaks to the migration patterns cited above, with better-heeled individuals bringing with them the sort of opportunities that weren’t available to many of those they may have displaced.

Adult education attainment, defined as the percentage of those 25 and over with a college degree, went from 52.6 percent to 54.9 percent, and high school graduation rates experienced a similar bump, 53.8 percent to 56.9 percent. Also of note were increases in third-grade reading and math proficiency, by 16 percent and 21 percent, respectively, and a 26 percent rise in the number of high-quality early childhood education centers within a five-mile radius. At the same time, the percentage of children eligible for free or reduced-price lunch slipped from 72.9 percent to 67.5 percent.

Early childhood education enrollment was off by an even greater amount, 58.7 percent to 32.7 percent – another indication that loads of families left Five Points and were replaced by young singles. Meanwhile, the percentage of teachers in their first or second year leaped from 9.4 percent to 23.4 percent, showing that the youth movement wasn’t limited to children.