Sara Fleming

Audio By Carbonatix

Early in the morning on Wednesday, September 11, a Denver police officer shook Angel Rayas out of the tent where he has been living near Sonny Lawson Park in Five Points. The wake-up call wasn’t out of the ordinary – Rayas says police wake him and others in his community along the block frequently, conducting “check-ins.”

But this time was different: Two days earlier, city workers had posted notices directing encampment residents to remove all personal property from the area. Rayas says that the night before, officers had repeatedly warned them they’d have to clear out.

More cops came, as did an inspector from the Department of Public Health and Environment. A few hours later, a Public Works trash truck showed up along with a privately contracted haz-mat team and a crew of inmates from the Denver County Jail, who were directed to pick up trash and personal belongings left on the ground. Within a few hours, the encampment of about fifty people was in disarray: Some residents had already packed up and moved on, others were lingering in the hopes they could stay, still others were debating whether they could leave their tents and blankets on the grass while they found food without risking them being taken.

Terese Howard, the principal organizer of Denver Homeless Out Loud, and other activists organized to pressure the city to back down from a full-scale sweep on that day, citing a pending lawsuit settlement between the city and lawyers representing Denver’s homeless population. In the end, the city allowed people living in the encampment to stay after the area had been cleaned, and DPD only issued warnings.

In August 2016, attorney Jason Flores-Williams filed the lawsuit against the city over its practice of taking unhoused people’s personal property during sweeps and cleanups, arguing it violated constitutional protections against unlawful search and seizures, as well as the right to due process and protection from cruel and unusual punishment.

The lawsuit settlement, reached in April, is set to go into effect as official city policy after a final approval hearing on September 23. It stipulates that the city must post written notice seven days prior to large cleanups and sweeps and 48 hours prior to the seizure of any personal property, as well as take measures to reduce the need for such cleanups, such as installing porta-potties, trash cans and lockers in areas where unhoused people reside.

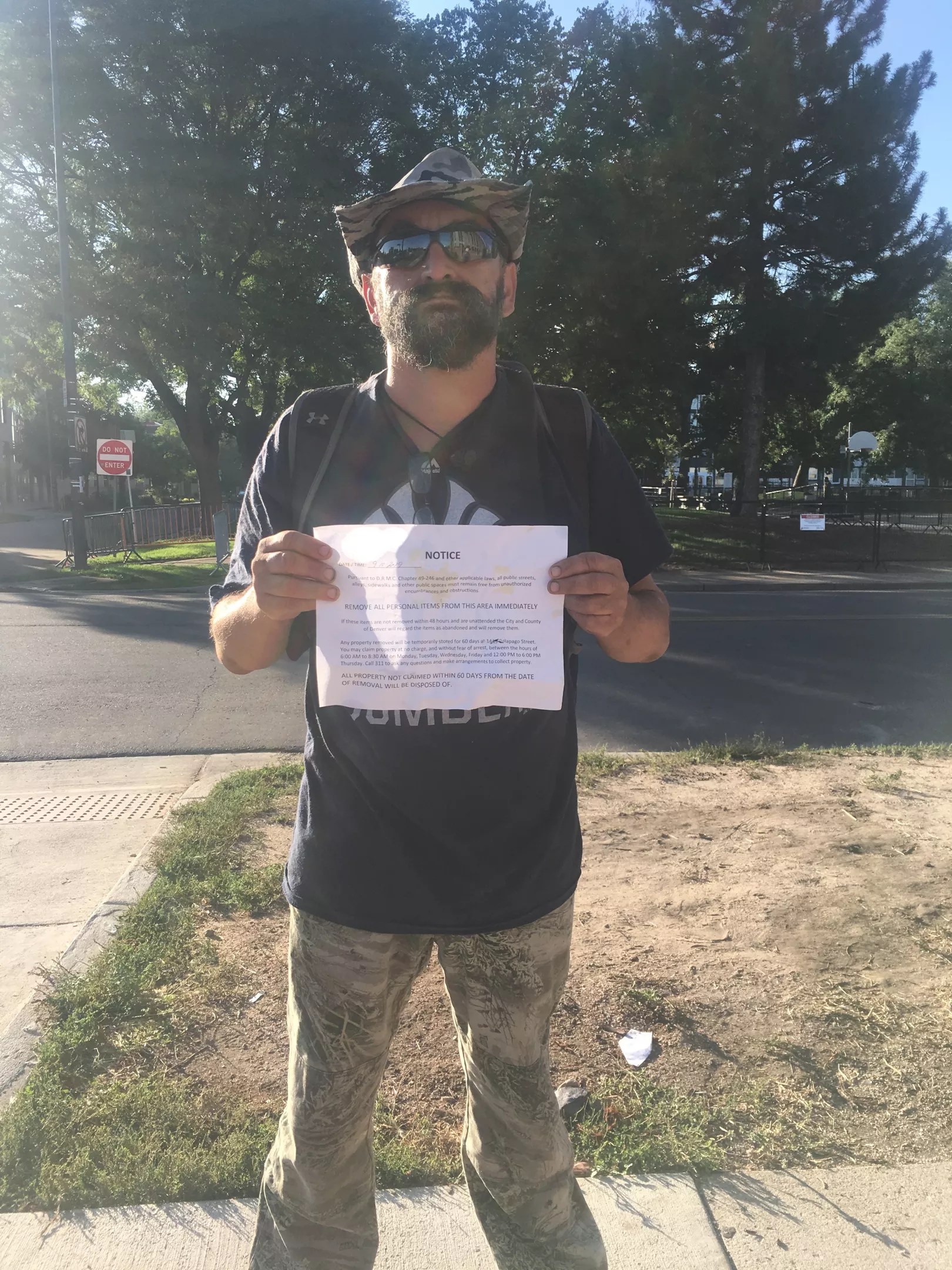

Wolf, who has been living in the encampment on 24th and California, holds a notice he received saying that the city will seize property unless it is moved within 48 hours.

Sara Fleming

“Before,” Flores-Williams says, “Denver would come to you and say, ‘Give us your shit and then you get out of here.’ Swept along. And then that stuff, which may be the only stuff you have in the world…ends up getting thrown in the trash. So if you think about it along constitutional lines, that’s the equivalent of walking into somebody’s house and taking your car. That’s what the lawsuit ultimately was about.”

Flores Williams says the lawsuit settlement is a “landmark expansion – or assertion – of rights, depending on how you look at it, for the poor and dispossessed.”

Even when the settlement becomes official, it won’t stop the city from legally being able to dismantle camps, ticket people for violating the camping ban, or effectively enforce it by threatening to do so.

Denver Police Department Sergeant Brian Conover, who supervises a DPD homeless outreach team, says he was merely enforcing Denver’s urban camping ban, which prohibits the use of any kind of shelter – tents, tarps, sleeping bags or blankets – on public property in the city. Conover told confused advocates on September 11 that the lawsuit would not change the Denver Police Department’s actions. “We are not doing any seven-day stuff, we are not doing any 48-hour stuff. We are enforcing the camping ban violation, that’s it,” Conover said of his team’s current enforcement policies.

Howard says what she saw – the number of cops and the presence of other agencies – indicated that the city wanted to sweep the encampment out completely on September 11, which would violate the settlement’s requirement to post notification seven days before large sweeps and cleanups. “If you do not define roughly fifty tents as a large encampment, I’m not sure what is,” she says.

The various city agencies involved in the enforcement didn’t have a clear line on what type of enforcement – sweep? cleanup? general check-in? – was intended for that day. Another sergeant who was briefly at the scene, Kenneth Chavez, told Westword that cops were backing up a health inspection based on “suspicions of rat infestation.” Tammy Vigil, a spokesperson for Denver Public Health and Environment, says the agency was responding to increased complaints in the area, but hadn’t heard specifically about rodent activity. Doug Schepman, a spokesperson for the Denver Police Department, deferred to Public Works as “taking the lead” on the enforcement action. Meanwhile, Nancy Kuhn, a spokesperson for Public Works, portrayed the enforcement as part of its regular cleanups, writing in an email to Westword, “The 24th and California location was becoming an area that needed some extra attention and we posted a note to let the people there know we were coming and to ask them to move their belongings so we could clean.”

No personal property was confiscated, according to Kuhn. Though police didn’t issue any citations or make arrests, they did issue written warnings that threatened such measures if people in the encampment did not leave.

Joe, a man who has been living in the encampment near Lawson Park and requested that only his first name be used for this story, lamented the city’s policies as he watched police tell him and others to pack up and move out of the area without directing them elsewhere. “You shouldn’t be able to take something from people if you don’t have something of equal or greater value to replace it with,” he said. “It doesn’t have to be where you’re just kicking people on like a can…What have you done? All you’ve done is taken people where you knew where they were and scattered them.”

Another resident of the encampment, who goes by the name Wolf, echoed that sentiment. “I’m diabetic. When I wake up in the morning I have to take my sugar, do my insulin, take my medication. … I’m trying to do what I have to do in order to get through my day. To have someone screaming in my ear and telling me I’m gonna get arrested just because I’m not jumping to as soon as they say anything, you know, it’s, I don’t know, it’s hard for me to do, and it’s even harder for the disabled and older people that come here. We’re trying to survive, and they’re trying to run us out of existence.”

According to Howard, these experiences with police, as well as the confusion between agencies’ roles in the sweeps, is par for the course. But Howard and Flores-Williams are hoping that when the lawsuit settlement goes into place, it will clear things up. The Denver Police Department and Public Works will have to be trained on the new policy.

Lisa Calderón, mayoral candidate and now Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca’s chief of staff, says her office is pushing for a meeting between Denver Homeless Out Loud and agency heads. “These are our constituents as well,” she says of the people living in the encampment. “A lot of this, for us, is around process, consistency, notice and reducing the confusion. We don’t want people to be afraid that they’re going to jail when a cleanup needs to happen, but a sweep shouldn’t be under the guise of a cleanup.”

Flores-Williams and Denver Homeless Out Loud have been doing outreach to the homeless community all summer to spread the word about the settlement. Flores-Williams estimates that he has talked to about 700 to 1,000 people in Civic Center Park, and says he has held three meetings at the Central Library, explaining the lawsuit and roleplaying how to assert the rights it establishes.

“This isn’t something that happened in a lawyer’s office and, woo hoo, we’re all great. This is a movement,” Flores-Williams says. “It’s about people taking responsibility for the enforcement of their own dignity and rights. It’s me going down on the street and handing everybody a tool: You can demand to be respected.”

Flores-Williams and civil-rights firm Killmer, Lane and Newman will split over half a million dollars in attorney’s fees. Flores-Williams says this was not about money, and that the fees are relatively modest for a high-profile class-action case.

Andy McNulty, an attorney with Killmer, Lane and Newman, has taken a step further. He filed a motion in court on September 10 to dismiss a camping ban citation against Jerry Burton, arguing the camping ban is unconstitutional, violating the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. “[The camping ban] is targeted at a specific discrete group of people who had no political power, because people with political power wanted those people to be forced out of the city of Denver,” he says. If granted a hearing, there’s a small chance a judge could overturn the ban.

Flores-Williams calls the settlement a first step, but says it has the potential to change the character of the city, as well as its record on homelessness. “This is the sort of thing that makes a city unique and special, is when it recognizes the dignity of every citizen regardless of what they have in the wallet or how much money they have in the bank,” he says. “Instead of being this sanitized and gentrified place where there’s no soul and no spirit, it’s a city where we’re all interacting and trying to figure out our way forward together.”