Jay Vollmar

Audio By Carbonatix

When Bruce Wayne Carl moved into the one-bedroom apartment on the end of an old rowhouse complex at 37th and Marion last year, each of the five connected units had their own gate, their own little front yard behind a wrought-iron fence. Carl hadn’t been there long when he noticed some workers messing around out front; when he asked, he learned that someone had offered to buy the antique fencing.

To Carl, the loss of the fence was acceptable, but he worried about the old pine that had grown through the wrought iron and become part of it. “What can I say?” says Carl, a 38-year-old musician and bartender who has some construction skills. “I love trees.” So he went out with an angle grinder and cut the tree free from the fencing so that it wouldn’t need to be removed, too.

That tree still hunches over the sidewalk, offering what shade it can, a single black rail embedded in its trunk – all that’s left of the wrought-iron fence. But like the building the fence used to front, this tree is hanging on in a rapidly changing neighborhood.

Bruce Wayne Carl lives in a very changing RiNo.

Evan Semon

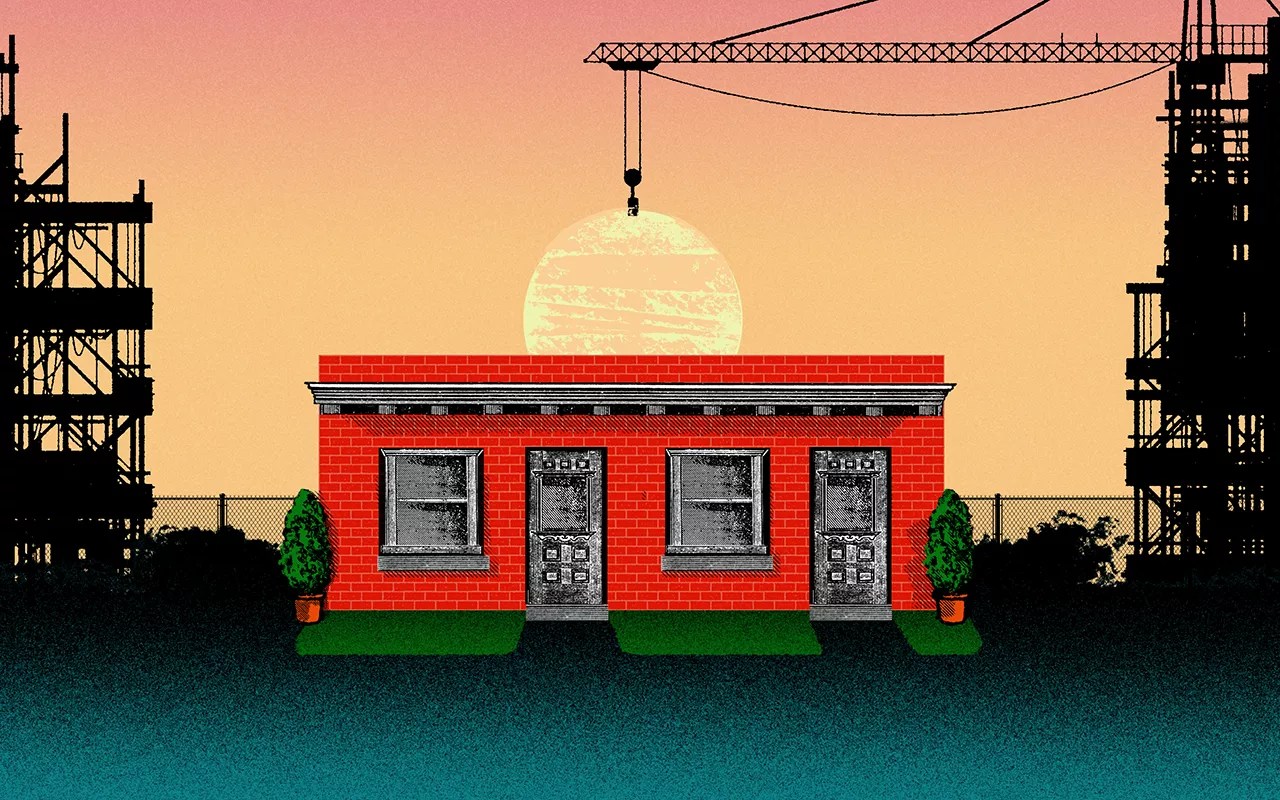

The rowhouses that stretch from 3739 to 3747 on Marion Street in Denver’s RiNo Art District – almost splitting the border between the Five Points and Cole neighborhoods – are the sort of multi-family dwellings that were plentiful in Denver a century ago. Unremarkable in architecture, utilitarian in purpose from the start, they’re nothing a historical society might champion, nothing that would cause much of a stir when the salvage companies inevitably come for the brass doorknobs and old lintels while impatient bulldozers wait to clear the land for whatever comes next. Something taller, sleeker, denser, the glass and steel too slick to hold much history.

And make no mistake: That will soon be the fate of this property, one of the last holdouts in an area once studded with small homes, storefronts and warehouses. It now lies in a valley created by the five-story Collective RiNo apartment complex to the south, the up-market seven-story Catbird Hotel to the north, and a still-under-construction nine-story apartment building to the west.

No original homes are left a block away on Blake; there are just two duplexes and a single two-story in the 3700 block of Walnut and a few more old residences on Downing before Five Points melts into a gentrifying sea of pop-ups and scrape-offs and new builds, mostly larger complexes or million-dollar townhomes. To the east of Marion, the Cole neighborhood, most of which is still residentially zoned, is just starting to evolve, turning over from the street corners inward, with a few holdout homes hanging on in the middle of the block. But most of the area dubbed RiNo nearly two decades ago has changed beyond recognition.

New construction continues onward and upward, increasing both population and profit. A property that had a three-story limit gets an exemption to allow five; five stretches to seven. Last year, some Curtis Park residents felt overshadowed by a proposed development between Lawrence and Larimer and 26th and 27th streets that needed a zoning change – and got it from the city.

And there are more big projects looming on the horizon.

The row of homes at 3739 to 3747 Marion Street.

Teague Bohlen

The rowhouses on Marion, which started out as affordable living space for working-class Denver and remain that way today, may have no historic significance, but over the past 120 years, they’ve built their own backstory.

Much of it is lost to history, but not all. The Denver Public Library does not have a complete digital collection of city directories, but it does have one from 1905, when the population of the Mile High City was somewhere between the Census marks of 133,000 in 1900 and 213,000 in 1910. Thanks to the Corbett & Ballengers Annual Denver City Directory from 1905, we know that the first inhabitants of the northernmost unit – 3747 Marion Street – were two gentlemen: salesman Edmund J. Taymans and George C. Junk, the latter listed only as working for a “Com Co.” By 1911, they’d moved out, and the apartment was the residence of one Louis G. Hagus, a driver for the Lindquist Cracker Company at 35th and Walnut. In 1915, it was the shared home of meatcutter Adolph H. Behr and Frank Gyllenston; in 1920, assistant foreman at the Welcker T&S Company Peter H. Fling lived there; in 1923, fireman Ross Rodebaugh and his wife, Nellie, were the occupants.

In 1924, the first edition of the Denver Householders Directory listed this address as the residence of Raymond and Mabel Wickell. Max and Helen Dendorfer called it home from 1926-29. In 1930, it housed Rich and Alberta Church, and in 1931 it was listed as vacant. William Haffner lived here from 1933 to 1935, John and Juanite Dombeck from 1936 to 1937, and so on for another 75 years, a line of residents likely ending with Bruce Wayne Carl.

This wasn’t a home where families lived for generations; it was a small place for a working man or a young family to rent while getting a leg up, close to jobs and public transportation. In 1905, the nearest streetcar stop was about a block away; 118 years later, the A Line is only a block to the northwest, and the light-rail stop at 30th and Downing is just a short walk to the south.

The exteriors of the rowhouses are sturdy red brick with some modest masonry details along the roofline and midway down the front facade. The roof is flat, probably tar paper originally; Carl says there’s not much in the way of insulation, but he’s okay with that. Five front doors in a row face Marion Street, mirrored along the alley with small enclosed porches that are little more than mudrooms, storage or both. The yards out back are used for both parking and gathering. There are lights strung from the trees to the clapboard porches that light up the darkness, allowing the nighttime sharing of beers, passing of joints, storytelling. It’s all a little messy, a little muddy, and well-loved in evidentiary fashion.

Bruce Wayne Carl rents the home at 3747 Marion Street.

Evan Semón

The inside of 3747 Marion has both age and charm. There are at least eight layers of paint on the remaining wood trim, probably more on the walls themselves. It’s a shotgun layout, 550 square feet straight back: one front room leading to a central room, at some point separated by pocket doors. Carl says that when he moved in, one pocket door was still hanging on. The front is his living space – plenty of room for a futon and a desk for his music and writing. The center room comfortably holds a king-sized bed with some storage space and a closet. From there, through a door to the right, there’s a galley kitchen with three more doors: one to a surprisingly generous pantry space, one to a small but serviceable bathroom, and the last the back door leading to the enclosed porch and backyard. The architecture is “still clearly early 1900s,” Carl says, and he loves every detail. “The moldings, the doors – everything is big. The ceilings are high, the walls are solid. It’s what you hope for in a place like this. It’s not some cookie-cutter place like they’re building all around us.”

Maybe not cookie-cutter now, but it might have been back in 1905, when the salesmen moved in. Carl says his rent is $1,100 a month, a solid deal for a one-bedroom, one-bath with a backyard and parking. Still, that monthly payment is more than twice – possibly almost triple – the annual salaries of Taymans, Junk, Hagus and all the other tenants who laid their heads at 3747 Marion in its early days.

Today the place is a far cry from what it was as recently as 1998, when current owners Jan Buckstein and Diane Watts bought the fiveplex for only $117,000. It was “pretty rough and tumble,” Watts recalls. All of the units were in various states of disrepair; one unit was heated only by the gas stove. The previous owners had purchased the building just a couple of years before and already wanted out. Crime was high, rent was down.

But Watts recognized potential. She remembers driving by, realized she could see downtown from the street in front of the units, and considered the values of similar city-center real estate in Chicago and New York City. “I knew I had to get that property,” she says.

The rowhouses are surrounded by new builds.

Teague Bohlen

Watts recalls that the area was largely Hispanic – the “for rent” signs she saw were only in Spanish, and they advertised rents of about $425 per unit. Many tenants came through as the years went on, most of them families that would set up plastic pools in the shade of the front yards, kept safe from the street by those wrought-iron fences. Mothers would sit there and talk with each other, sipping cold drinks and watching the kids splash.

Not all of the residents were so wholesome. Watts recalls a few stories about drug dealers and prostitutes. The most remarkable story was the 2008 murder of Henry Blair by Warren Worthington, a tenant of the complex. Worthington was the son of Colin Powell’s second-in-command in Vietnam, and ran a nearby body shop; he’s now serving life in prison. “Such a sad story,” Watts says.

That episode aside, she and Buckstein have enjoyed owning the property. “It’s been a good investment, but it’s also been good to rent to people who need a place like this to live,” says Watts. “Working people, nice families. It’s been a good way for us to give back a little.”

But now they plan to sell, because they both want to retire. And in this hot market, it’s unlikely the next owner will want to play landlord to just five tenants when there are more lucrative possibilities.

Evan Semón

The current occupants who could lose their homes are cut from the same cloth as many of the residents who’ve lived here through the decades. Next door is Yan Nuang Soe, a Myanmar refugee who drives for Uber and works on EDM in his off-hours. The middle apartment is where Katy Chapo lives; she’s a poet and a chef. One apartment down is Cory Sahr, who is also in the service industry. On the other end is Manny Lakanu, a chef by day but a rap artist, too, with a sonorous baritone voice perfect for spoken-word art. Together, they are and aren’t a family; they come from different backgrounds and ended up in the same complex by circumstance.

But they share that common backyard: They put together a garden last summer, and have a firepit where they can visit with each other. Carl helps Yan when he runs into language barriers, on visits to the DMV and other spots. Katie shared a poem with Carl when he moved in as a gesture of welcome. They are united, for now, by place, both geographically and in life.

Carl says he doesn’t know how long it can last; he was only able to move in because the previous tenant anticipated that the rowhouse would soon be sold and relocated before he was forced to.

Carl hails from Queens originally, and yes, Bruce Wayne is his real name. “It got me in a lot of fights as a kid,” he recalls. “I didn’t use it for a while, but it’s my name, you know? So I’m embracing it.” And Gotham – or New York City, to the non-comic-book world – wasn’t his scene. So he traveled around a bit and ended up in Portland, Oregon, for about ten years; in 2013, he moved to Denver because he needed a change. “The Pacific Northwest can be a gloomy place,” he says. “When I heard how much sunlight Denver gets in a year, I decided to get out of the rain and head toward the light.”

“She wanted to make changes and raise the rent, so they didn’t renew my lease.”

He lived in Arvada before relocating to 3747 Marion, a move propelled by a situation familiar to renters in metro Denver. “A new owner had just bought the place I was in and wanted to start renovating,” Carl says. “She wanted to make changes and raise the rent, so they didn’t renew my lease. This place came up; it was exactly what I was hoping for, and I did everything I could to get in here. It’s the way things work, right? Something bad happens, something good happens. It was perfect and amazing and serendipitous.”

Carl used to bartend at the Mercury Cafe under original owner Marilyn Megenity, before she retired and the club changed hands mid-pandemic. He still works in the service industry, while also developing his music career. “I’d always written poetry,” he says, “and then the poetry turned into songs. The music culture is so strong here in Denver that it inspired me to jump into it.”

One of the first songs Carl released – under the name Warbler BC; he’s since gone back to using his real name – was “Starry Gown,” which was included in collection #3 of Timestamp, a compilation album series of regional music made during the pandemic; that program was a collaboration between Free People Records, the Underground Music Showcase and Loudspeaker. “That was amazing,” Carl says. “I got a lot of great feedback, and it opened things up nicely.”

He says he was never aiming for a specific genre of music; he didn’t know how to describe it until he got some input from reviewers, who said that it most closely resembles “dark dream pop” with some gothic influences. He now calls it indie rock, but at the same time dislikes labeling it. “It’s still evolving, I think. On the plus side, a lot of people have remarked that it’s very authentic, but it’s also not specifically my goal,” he explains, adding that he likens it to making soup: “You never quite know how it’s going to turn out, but you keep adding ingredients, and hopefully it’s a wonderful surprise, something that’s never been tasted before.”

Teague Bohlen

Carl has been making that soup on Marion Street for only about a year, but he’s still borne witness to a lot of changes to the skyline. “When I moved in, that skyscraper over there that’s constructed up to its third floor now was just a hole in the ground,” he says, pointing to the nine-story “multifamily project” in process to the west. “Before that, my neighbors say it was just old houses with squatters, homeless people living there. It’s all going up so incredibly fast, which of course is making everything around it change just as quickly. It’s remarkable. And it’s everywhere.”

He’s heard that the owners of the fiveplex will probably sell this summer. “We’re all hoping it lasts a little longer,” he says, “but it probably won’t. They’ve already told us it’s inevitable.”

What’s also inevitable is the loss of the creative community when creatives can no longer afford to live in the community they’ve helped to build. It’s an old story in RiNo, and all over: Artists of all stripes come into a part of town because it’s affordable; they make it attractive because of their energy, because of their creative works. Prices go up, developers come in, and the creatives are priced out.

“We’re all just living and working and trying to enjoy the time we have left here.”

Carl doesn’t begrudge the property owners wanting to make a profit off his place, but as he points out, “This is a creative town. We couldn’t even live here without places like this. The people right next door in the condominiums with the Tesla chargers and the chrome gates and everything, everything, everything – they throw away stuff that we couldn’t afford with a month’s pay.”

But there’s a more incalculable loss. “It’s a kind of lifestyle that’s going away,” he says. Shared yards, incidental communal living, knowing your neighbors to a degree that they become your friends. Most buyers and well-heeled renters today are looking for their own space, not one that they share. But absolute privacy is a perk; it’s the opposite of what American life used to be, before six-foot backyard fences and divided patios.

“Things are always changing,” says Carl, but change begets change, and not always in the way a city might want. “Things are always in flux here. I think that adds to the creativity, keeps things from getting stagnant. We’re all just living and working and trying to enjoy the time we have left here.

“That’s what we do. Live moment to moment. Deal with the future as it comes at us. It’ll be sad to leave this place. But what’s even more sad is that there’s probably very few places like it left to go.”

These last holdouts are disappearing fast in Denver.

Do you know of a holdout house worthy of a profile? Post a comment or send information to editorial@westword.com.