Evan Semón

Audio By Carbonatix

Members of our community are heroically holding the line of democracy by serving as elections officials, but they’re feeling the heat. A few, like Amber McReynolds, have moved from the Denver Elections Division onto a national stage. Others, like Denver Clerk and Recorder Paul López, are preparing for the next very local challenges. And still more, like Pam Anderson, who ran for Colorado Secretary of State and lost to incumbent Jena Griswold, have not given up on the process.

Like Anderson, George Stern, past clerk and recorder of Jefferson County, is contemplating his next move. Stern served as Jeffco clerk during the 2020 presidential and 2022 midterm contests, constantly putting out fires of controversy fueled by misinformation – while simultaneously putting out actual fires as a volunteer firefighter. He did not run for reelection, though, and we caught up with him after his successor was sworn in, when he felt free to be candid about being a nonpartisan clerk in a swing county during a polarized era.

Helen Thorpe: I’d like to help others understand your background, and then I want to ask you about the threat level in this arena, and after that perhaps we could head in a more positive direction and talk about how we make sure things get better.

George Stern: Sounds good. Certainly what I’ve been living in the last four years.

Where did you grow up?

Maplewood, New Jersey. My parents were both journalists, and they met in D.C., at the Washington Star before it went defunct. Then my mom was at USA Today and freelanced for a bit. My dad worked at a couple different places before a long career at the New York Times. I have two older brothers, so there are three boys.

Maplewood’s school district was half Black when I did K-8 there. Then we moved to New Hampshire, and I lived there from fourteen to eighteen, and it was super different. That, plus exposure to national politics was my [epiphany]: “Oh, there isn’t diversity everywhere. There are inequities that I care about and that should be talked about nationally.” That all came together with me starting to care about politics.

How did you start working in that sphere?

High school in New Hampshire was when I became politically active; it was the 2004 presidential election. Because it was the New Hampshire primary, we had all the candidates coming through, and that’s what piqued my interest.

I had been raised by two journalists, and it was required that we be aware of what was going on – but not political. When I would say, “Well, who are you guys voting for?” They would respond, “We don’t talk about that.” It was very journalistic. They were telling me what was going on, not their thoughts on what was going on.

Then I became the head of the Democratic Club in the fall of my junior year. And I never had worse grades in my life. I decided that presidential politics was far more important and just let everything else go, because I went all in.

Was there somebody running who inspired you?

For most of the club, it was probably Howard Dean. He appealed to young people, to progressive folks. Whether it was because I didn’t have enough political background or because I was the son of journalists, I took a neutral approach. I worked for all of them. Our club would say yes to anyone who asked for help, making phone calls, knocking on doors, doing whatever they needed us to do.

How did that interest in politics deepen during the two years between high school and college?

I graduated high school in 2006 and took two years off before going to college. During that time, I worked for John Edwards, who was running for a second time. In 2004, Edwards had been the close second behind John Kerry and became his running mate. Then from the day John Kerry lost, Edwards was running for president again.

He was the only person talking about the inequalities that I had seen. His theme was two Americas, and going from what I had seen in New Jersey to what I had seen in New Hampshire, it resonated. He was the only one talking about poverty and about educational inequality.

So I deferred college and moved to North Carolina. I don’t think my parents were thrilled about it, but they said: “You do you. You’re eighteen, you’re an adult. But you’re on your own. We’re not funding this excursion of yours.” So I ensured I had a paycheck before I went. I lived in North Carolina for a year and a half, until [Edwards] lost the first few states and then dropped out just before Super Tuesday.

Then you went to college…

George Stern is in the public eye even when not in public life.

Evan Semón

I came into Columbia as a twenty-year-old, and my birthday is in October, so within three weeks, I was a 21-year-old freshman. I loved campus; I spent all kinds of time on it. I found friends very quickly, but I lived on a floor with seventeen- and eighteen-year-olds and did not feel as connected to them. And that probably pushed me more outside the dorm and into the campus in the city. But I was in a hurry because I had come in at that age, so I did it in three years.

Between Columbia and Harvard Law School, I worked as a teacher out here, down in Colorado Springs. I taught high school math and was a baseball coach.

Can you explain how in the next three years you worked for one of our former governors, at McKinsey & Company, a global consulting firm, and in the White House? Were those jobs you held after you finished your law degree at Harvard?

I worked at those places during law school. I knew I wanted to be out here in Colorado, so I came out here both summers. The first summer, I worked for former governor John Hickenlooper in the Office of Legal Counsel, and also at a law firm. It’s common in law school to split your summer between two internships, to let you get more experience. I divided my time between the public sector and the private sector. I decided law firms were not for me, but the public sector could be. My second summer, I did an internship with McKinsey to gain more experience in the private sector, and also did an internship in the governor’s marijuana office.

In between those summers, during my second year of law school, I got a law clerk position in the Office of White House Counsel for Barack Obama, and Harvard let me do that for credit. I spent from January to June of 2015 in the White House, where there are 25 full-time attorneys and five law clerks who are all law students. The Affordable Care Act came before the Supreme Court, same-sex marriage came before the Supreme Court, and the immigration executive orders were being defended. It was an amazing time. We were in what President Obama called his fourth quarter, when he had no more elections in front of him. It was fun to govern because we were using the power of the office to push the agenda through. And then I had to leave to make it out here for my second summer, where I had agreed to work in the marijuana office. …

I can’t hold a job, is the story of my life; my wife was reminding me of this. She’s been the breadwinner for us for a while. You know, I was a teacher for two years, so I did not make much money, and then I went to law school, where I never did paid gigs for very long. Maybe I made a few thousand from the law firm my first summer and then McKinsey paid me well for half a summer. When I worked for the State of Colorado, neither of those jobs were paid. And then I was deep in debt when I graduated from law school. But I had these awesome experiences.

When I graduated, I happily accepted a job from McKinsey as a management consultant and worked for about two months, and then Donald Trump got elected in 2016. And I said, “Oh, I need to get back to the public sector.” I remember I was out of town on a project on Election Day, and was out bowling with a colleague of mine. It was late, and we just wanted to get out of the office. The election results came out, and I said to him, “I don’t think I’m going to be here very long.”

And I was there for about another six months.

George Stern was elected Jefferson County Clerk in 2018.

Evan Semón

Why did you want to run for office?

I knew I wanted to be in the public sector. I did not know I wanted to run, but the legacy created by an administration I had loved, it was all at risk. A year prior, I had been defending the Affordable Care Act, defending same-sex marriage, defending immigration executive orders, and now a person who sought to undo all of that had been elected. I had liked the idea of working in the private sector as a way to gain experience that I could use in government and pay off my debt, but when things were not good, I felt I needed to get back to the public sector. I had no idea what the path would be, and just started showing up to a bunch of stuff. My wife and I would show up, and often we were the youngest people in the room by like forty years. We had almost all elected Republicans in Jeffco at that point. The clerk and recorder was running for reelection, and no one was willing to challenge her because she’d won thirteen out of thirteen previous elections. So I looked at that office and found that it had the DMV under it – which I describe as a consultant’s dream, because it is everybody’s least-favorite agency, and consultants like going to the worst and trying to make them better – and then elections, which I had been passionate about for a long time. So I said, “Sure!”

I’ve trained as an elections judge, but the laws that govern elections are so complicated.

And I learned that on day one in the job, because I thought I knew the law pretty well, and I had a lot to learn. Staff is amazing. I mean, the talent drain happening in elections is a big problem, because we depend on career people who know what they’re doing.

Let’s talk about that. Threats have happened in various counties and at the state level.

This has been a challenge for the last few years. Certainly, it was something I didn’t intend to navigate. Clerks flew beneath the radar until 2020, and then we learned pretty quickly that anytime we responded to a threat, we would get many more. When someone asks me about them, I say, yeah, they’ve increased, but I don’t like to draw attention to that. You’re often telling them why they’re wrong, which just feeds the troll.

What bothered me more than anything else was how it would affect the staff. You could physically see it taking a toll on them. Right after the 2020 election, I mean, I’m a Jefferson County Clerk and Recorder, and I was on CNN, you know? That shouldn’t be happening. That happened because of the climate we were in. But the brighter my star shone, the worse my staff got it. And the more I faded from view, the better it was for them. And so that became a difficult calculus.

Some measure of speaking out was important because it helped legislation pass that brought more federal dollars to fund election security, but especially when I decided I wasn’t running again, I was like, “I think I need to insulate staff from this.” At that point, I decided the incoming threats needed to come through me so the staff didn’t know what people were saying and doing. It was hard to see, you know? Front-line staff members would be answering the emails, and they would get someone saying crazy things, and they would be like, “Oh, God, I really didn’t sign up for this.” So we tried to protect people from what was ultimately really, really sad.

What are some developments that you think are worth sharing?

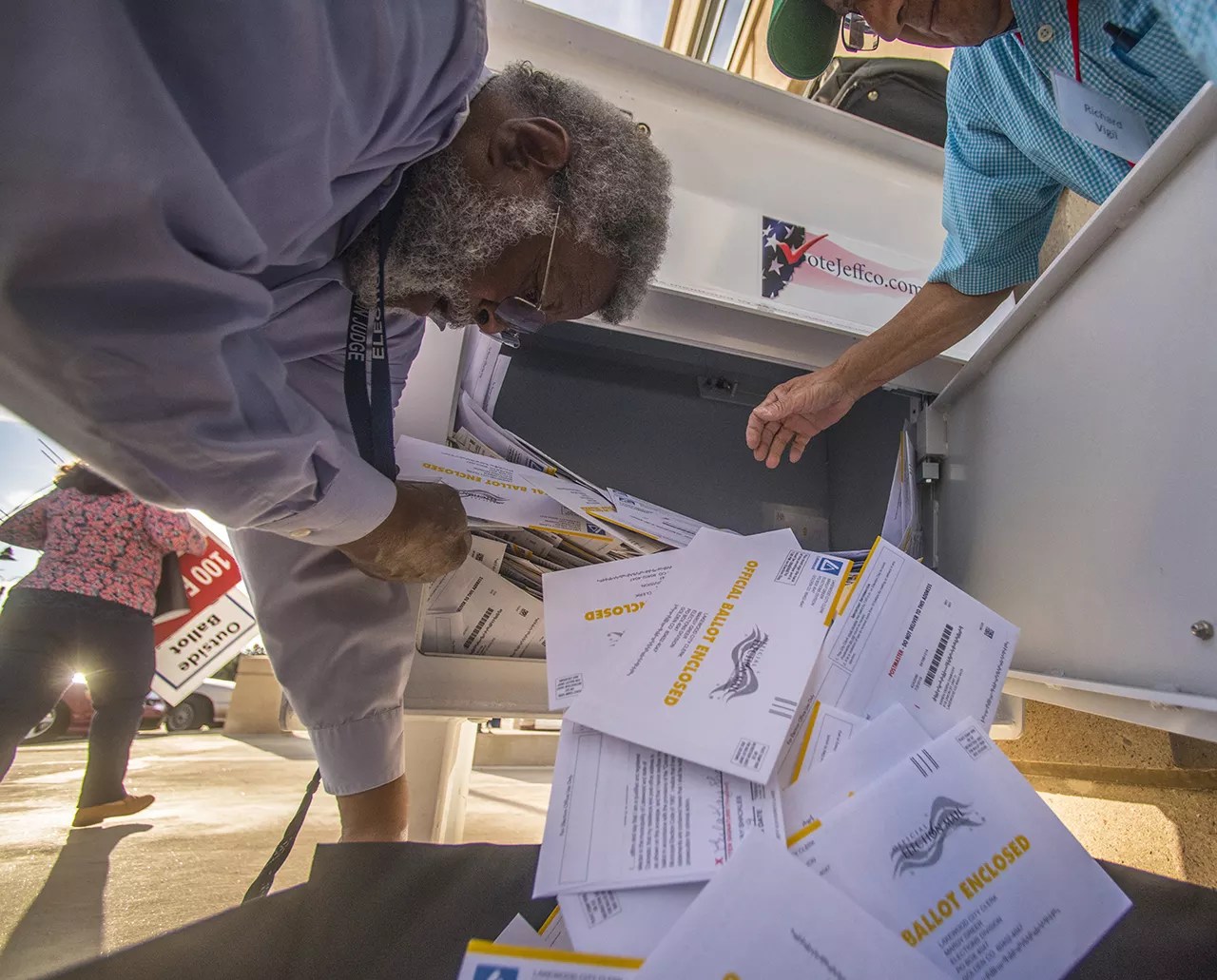

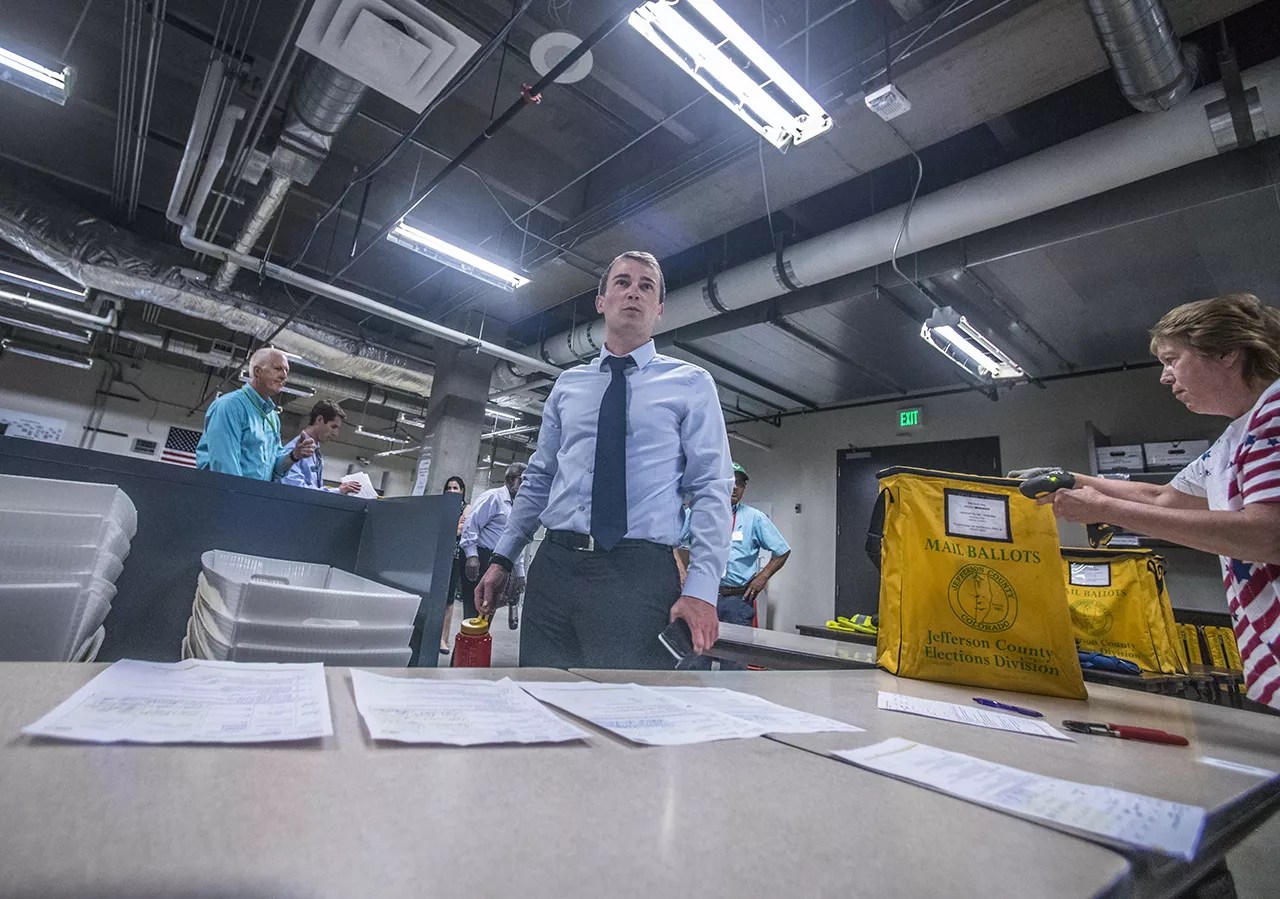

Despite all of this, I hired 700 election judges this past November. In this past election, there were 700 people who were willing to come forward and help. Both by law and intentionally, they’re of different political affiliations. So I had 700 people from across the political spectrum who knew there are risks in this realm, who are staffing vote centers that anyone can walk into, and who are working at our ballot processing facility. We’re a large swing county. They know that puts targets on you, and they were raising their hands to do the work. That gives me hope. And the coolest thing to see is, at every single table, a D is sitting next to an R. At every single vote center, you’ve got people who – you know, in the early days, they’re sitting there twiddling their thumbs – are forced to talk to people of different political affiliations for nine hours at a time. And it’s amazing to watch. People of different political affiliations are laughing together, they have brought in baked goods for each other, they are asking about how a kid’s music performance went, or how a sports game went. They care about each other. And when they come back for the next election, it’s like watching people on the first day of sleepaway camp, with these friends they haven’t seen in ten months. They’re hugging and catching up and they couldn’t be more thrilled. We are creating this every year and proving there is still the ability to get along, to be neighbors with people, even when you don’t agree with them on everything.

The divisiveness is part of the national rhetoric, but it is really on the fringe. Most people just care about having a functioning democracy where we all get a voice. And it leaves me, as someone who has to hear the absolute worst from the fringe, to see this incredible example of democracy at its best, of people signing up to work with people of different affiliations to make our democracy function. I’m left with net hope for the future; that’s what inspires me and others. I tell those 700, go tell all your friends and neighbors about what you experienced so we spread this hope.

I think the positive message is what’s been missing from the news.

Exactly. During this past election, we would dig into our website traffic, where we have pages of information on election security, answering all the questions and debunking all the misinformation. And then pages on how you register to vote, where is your voting location. In some cases, the traffic was twenty to one in favor of the how-to-vote pages. On the security page, there wasn’t much traffic – people didn’t really care about that. What they cared about was how to vote. They cared about finding their voting location, they cared about turning in the ballot. But the media coverage, every interview request I got, was about election security. This is the point: The coverage is not matching the reality. And look, it’s a sexier story that two years ago, a sitting president tried to overthrow the results of the election to stay in power. I get that. But at the end of the day, what most people were asking our office about was, how do I vote? They would say, “I trust this process. I don’t care about the conspiracy theories or your responses. I care about: How do I cast my ballot so I can participate?”

George Stern oversaw the Jeffco election office.

Evan Semón

What kinds of mistakes do people make?

The biggest mistake in our system is waiting until the last minute. It’s much easier if you don’t procrastinate.

We mail ballots all over, to Iraq and Afghanistan. Students might go to college out of state, but they consider Colorado their primary residence, not the dorm room, and we’ll mail them ballots. You can register to vote up until 7 p.m. on election night, but you have to do it in person if it is less than eight days out. So voting becomes harder the longer you wait. Vote centers are boring places for the first two weeks that they’re open. But then come Monday, and then really come Tuesday [Election Day], and they are hopping. So don’t wait till the end if you don’t want to stand in line. Come anytime in the two weeks before, and you’ll have it to yourselves.

What else do people do wrong?

People will forget to sign, or they’ll sign their spouse’s envelope. Take the signature seriously. People don’t think we’re checking it. They think it’s like, you know, signing a credit-card pad, which no one really scrutinizes anymore. We check every single signature. Sign like you signed the last few times. If you sign the ballot on the steering wheel of your car and it’s a terrible signature, it will get rejected. Our process lets you address that, up to eight days after, but that’s another step. Don’t make yourself have to go through another step.

Your successor was just sworn in. How does the next clerk get ready for the job?

The clerks association is very good about trainings. We get sworn in during odd years, so there isn’t an election until November in most counties, so you have time to learn. It’s harder in the smaller counties, but in a county like Jeffco, I had just over a hundred employees, and only two of them left with me. So there’s a ton of institutional knowledge in that building.

Do you favor having elected clerks or appointed clerks?

It’s a very good question. When I was first running, and early in my time in office, I agreed with many people who said, “Isn’t this crazy that we are electing nonpartisan election officials, and because of the cycle we do them in, we run partisan?” You know, I had a D by my name, and most of my colleagues who ran had Rs by their names. And I think electing a nonpartisan clerk in a partisan race is silly. But the reverse argument, which I think holds a lot of merit, is that the way to have the most accountability is to have the person directly accountable to the people. Having a layer of elected officials or bureaucrats in between the voters and the clerk would make the clerks accountable primarily to someone who might ultimately be on the ballot, which you never want.

I think ultimately, by being elected, I was fully independent. I did not report to the commissioners. I did not report to the secretary of state. I reported to the voters.

It would be a problem if I reported to three elected county commissioners whose elections I had to oversee. That would worsen a perception problem that exists.

The concern many have is this hypothetical concern that you’re putting partisan people in office. And if people were appointed, you could appoint independents or whatever. I will say from personal experience at all levels of government, first, appointees are rarely apolitical. They are sometimes even more political than elected officials. But second, the vast, vast, vast majority of clerks do not do the job in a political way. Some of my closest friends are my Republican colleagues who are clerks. I am inspired by many of them. I consider them heroes for the ways they’ve been standing up to things in the last few years. We are examples of nonpartisanship. We try to be nonpartisan in a way that’s good for the office itself. But being elected lets us stay accountable to the people rather than to some official who might try to force us to do things in a certain way.

Why didn’t you want to run again?

No easy answer. A lot of it was the feeling that I had campaigned on doing a set of things four years ago, and we did them. I had accomplished what I had set out to do. I think we dramatically improved, and I worry that if I did four more years, I would get stale. It was better to let someone new come in, with new ideas. Also, my wife and I had two kids while I was in office, and that just changed the pace of life and what I’m looking for out of my career at this moment. That was a big part of it.

After one term in office, George Stern moved out of the Jeffco clerk’s office and back into private life.

Evan Semón

Do you have a vision for your future?

I will certainly be in public service again at some point in my career. I have a desire to serve. But I loved the private sector while I was in it, so my next role might be private sector. If I can find interesting work that offers hard problems to solve with good people, that’s what fills my cup. But I envision being back in the public sector sometime in the next two to ten years, because this is where I get most filled up: by the impact of the public sector. There’s an old Methodist saying, “Do all the good you can for all the people you can for as long as you can.” And that’s ultimately what I want to do. I want to have as much impact as I can. I’ve added to that, in the last two years, a caveat: “…while also prioritizing your family and making sure you’re being a great and present dad and husband.” And that’s important to me.

I have one more question. Why did you want to fight fires while also being clerk?

I continue literal firefighting today. Golden is a combination fire department, where we have both volunteers and career staff. Most rural communities are all volunteer, while most cities have all career departments. It’s often in the suburbs, in that urban-rural divide, where you get these combination departments. In Golden, we were exclusively volunteer as recently as ten years ago, and then we started transitioning by hiring some career people to be on duty at all times. But we don’t have enough of them to get a rig out the door, so we have to have volunteers to supplement. I started doing that before I was in office, and because it’s a volunteer position, I could continue it while I was in office, and I’m continuing it after. It’s my favorite thing I do.

Why is that?

As I’ve said, what I get filled up by is solving hard problems with good people. I mean, we speed around the city solving problems. I pinch myself every time we roll out of the bay on the rig. Let’s see if we’ve gotten a call while we’ve been sitting here. Yes, at 1:56 we did get a call. So once I leave, I will turn my pager on, and if we get a small call that this shift crew can handle, I don’t do a thing. But if we get a bigger call, I’ll respond to the station and be on the second rig that goes out of the bay.

Honestly, it couldn’t have been a better thing. My fellow firefighters, we range in politics from the far right to the far left. We range in income. And we have all kinds of professions: We’ve got career firefighters, law enforcement, teachers, engineers, attorneys and elected officials. It’s such a cool cross-section. Good elected officials try to find people who will stand up to them. My fellow firefighters are happy to give me a ribbing any day of the week.

This interview was lightly edited for space and clarity.