ksenia_bravo/iStock

Audio By Carbonatix

As demonstrated by a recent study, the gap between the healthiest and least healthy counties in Colorado is vast, and the reasons for these differences have every bit as much to do with nurture as they do with nature.

“What really affects your health more beyond access to health care and genetics is the environment you live in,” says Dr. Tista Ghosh, interim chief medical officer for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. “Do you have access to good food and a safe environment? Do you have the ability to exercise? All these social structures in place that support your health play a far bigger role than health care.”

The latest data comes from the “2019 County Health Rankings” assembled by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in conjunction with the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, and the Colorado-specific report underscores Ghosh’s point about factors that are tangential to health playing a major role in determining the overall well-being of a community.

Take the impact of high housing costs, which make it more difficult for people living under such circumstances to afford healthy food, proper medical care and so on. Of Colorado children living in poverty, 61 percent of them are part of households that spend more than half their income on keeping a roof overhead. This level of housing-cost burden impacts between 8 percent and 23 percent of households in assorted counties in the state.

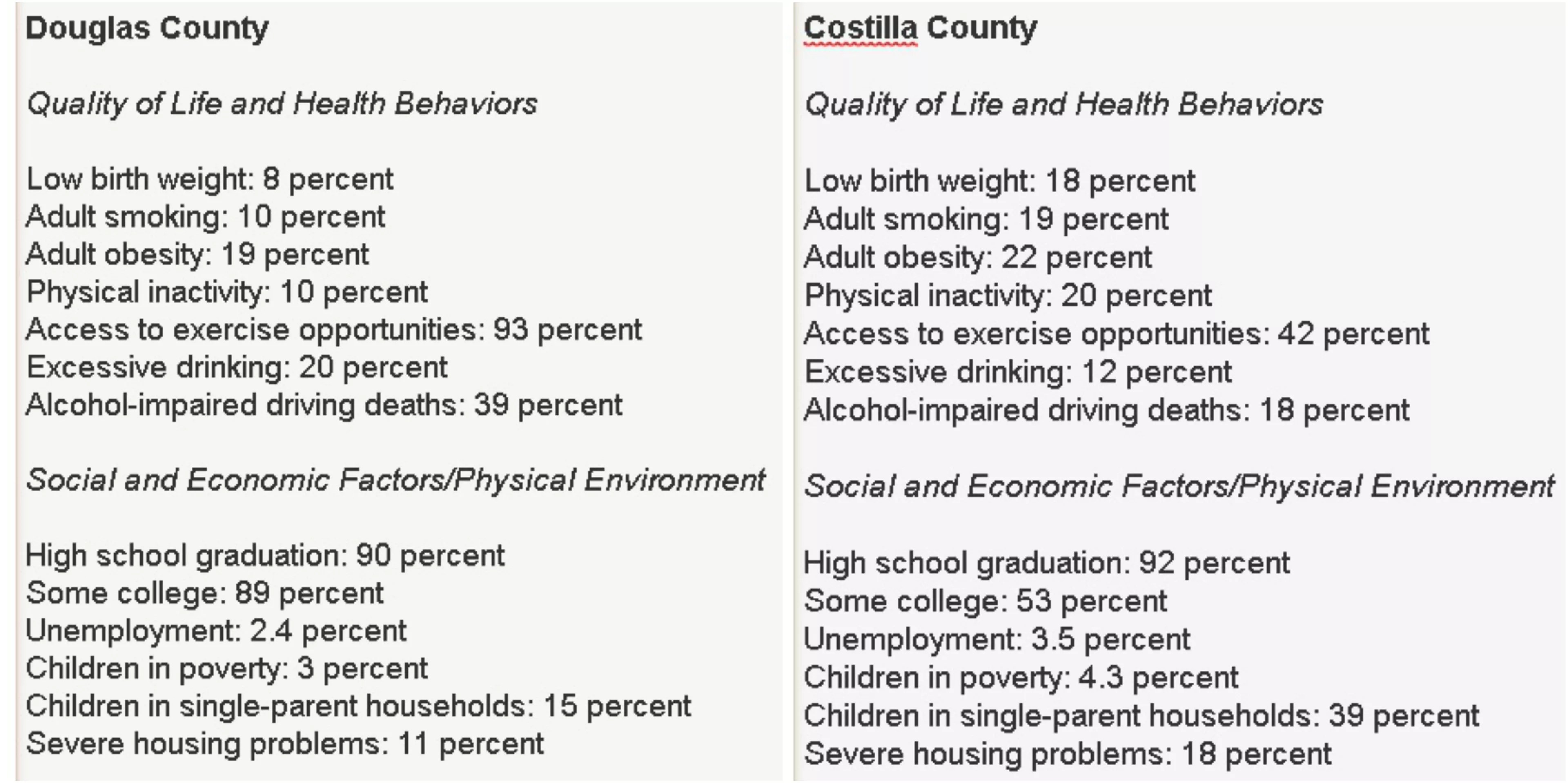

The report ranks sixty counties (excepting four for which complete statistics weren’t available) from the most to the least healthy, and those at the top of the chart tend to be urban and affluent. The metro area’s Douglas County lands at number one, followed by Pitkin, Eagle, Boulder and Broomfield counties. In contrast, those at the bottom of the list tend to be rural and economically challenged. Costilla County, in southern Colorado along the New Mexico border, sits at number 60, preceded by, in reverse order, Huerfano, Las Animas, Conejos and Pueblo counties.

Why did Douglas and Costilla end up on opposite ends of the roster? The numbers tell the story. Below are side-by-side comparisons of key categories. As you’ll see, the ones in Costilla are consistently worse than those in Douglas and sometimes twice as bad or more. The only significant exceptions involve alcohol consumption and drunk-driving deaths, which are more problematic in Douglas than Costilla.

Westword image

These figures illustrate issues that Ghosh understands well.

“We see this all the time,” she says. “It’s a sad but true fact that poverty is probably one of the biggest causes of disease or negative health outcomes. Counties that are more affluent tend to have better health outcomes than counties that don’t.”

This phenomenon is known in the public-health field as “the social determination of health,” she goes on. “People think health is all about health care. But actually, access to health care only determines about 10 or 20 percent of your health. Other social norms determine the rest.”

Bridging the divide exemplified by the Douglas and Costilla stats is “a huge challenge,” Ghosh admits, “and it’s one we’re actively working on, though it’s not so easy to solve, obviously. We have an Office of Health Equity at the state, and a Health Equity Commission, a group from around the state that advises us on these issues. We look at the data and what’s driving health issues, including housing, transportation and food access, and we try to work across sectors so we’re not only staying in the health lane.”

For instance, “If CDOT is going to build a road somewhere, we ask, ‘Have we thought about the health considerations? Have we thought about food access in a certain community? And how can we increase SNAP [Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program] enrollment?’ SNAP falls under the Department of Human Services, so we try to work with other departments as far as moving the needle on some of these issues [goes]. But these are big structural, systemic issues that don’t go away so quickly.”

Despite these problems, Colorado as a whole remains healthier than plenty of other places in the country. “We’re the least obese state, for example,” Ghosh acknowledges. “So if you’re just looking at the overall data, you’d think we’re doing pretty well. You need to get more granular and look at local-level data. Then you’ll see that not everybody is doing well, and not everyone has the same opportunity to do well.”

Cultural differences, including parts of the state where smoking is much more prevalent, are part of the picture, too. But while the CDPHE funds education efforts on topics like these in counties with overall health struggles, Ghosh says the state is also “trying to empower local communities themselves to work on these issues. We have grants called Communities That Care, where we’re actually giving some dollars and helping to build infrastructure in the communities so people will get together and look at their health data and decide what their biggest problems are and how they want to tackle them instead of us telling them what to do. They’re choosing their own leaders and getting buy-in to broad engagement in the community.”

In the meantime, Ghosh sees the latest report and others like it as “a call to action” in a state where health equality from rich counties to poor ones has not yet been achieved.