Photo Illustration From Shutterstock Images

Audio By Carbonatix

Just about every schoolkid in Jefferson County knows that you don’t have to go very far to find a place where monsters partied. The place is Dinosaur Ridge, a segment of the Dakota Hogback that runs along the southwestern edge of the metro area like an undulating backstop, separating the hubbub of the plains from the foothills beyond.

Geologists believe the hogback was created fifty million years ago, in the same upheaval that formed the Rocky Mountains. A hundred million years before that, Dinosaur Ridge wasn’t a ridge; it was the shore of an ancient seaway, a popular beach destination for the Jurassic set.

In 1877, Arthur Lakes, a professor at the Colorado School of Mines and one of the premier fossil hunters of his day, uncovered an impressive collection of dinosaur bones on the west side of the ridge, including remnants of Stegosaurus, Apatosaurus and Allosaurus. In the 1930s, while building the Alameda Parkway over the hogback, workers found hundreds of dinosaur tracks embedded in the sandstone on the east side of the ridge. Over time the find became recognized as the most significant track site in the country – not only because of the sheer volume of prints, but for the quality of their preservation and the tremendous information they yielded about the creatures that had made them.

For nearly thirty years, the track site has been maintained by a volunteer group, the Friends of Dinosaur Ridge. The group operates a modest visitor center and takes the curious up to the tracks in vans. (Alameda was closed to auto traffic over the ridge several years ago to help protect the site.) The place now attracts 160,000 visitors a year, including busloads of schoolchildren. And important research continues to be done there.

Last year, Martin Lockley held a press conference at Dinosaur Ridge to announce the latest eye-opening breakthrough. A University of Colorado Denver emeritus professor and one of the world’s leading experts on dinosaur tracks, Lockley has been studying the Dinosaur Ridge repository for decades. His team had recently discovered dinosaur “scrapes” at the ridge and at other sites in western Colorado, which he believed to be evidence of prehistoric foreplay – a kind of courting ritual between giant theropods that required the males to demonstrate their prowess at scooping out a nesting location, similar to what some species of modern birds do.

“This is really a big deal,” Lockley explained, “because it helps to verify the close relationship between carnivorous dinosaurs and birds…. I rank it as one of the top discoveries of my career as a paleontologist.”

The announcement triggered a blizzard of articles in media outlets in several countries, oozing with references to dino whoopee and secret love nests. But even as news of the discovery was spreading around the world, another lumbering, awkward mating dance was under way in Jefferson County, one that could have a profound effect on the future of Dinosaur Ridge and the Rooney Valley below.

Dinosaur Ridge, the most significant dinosaur track site in the United States, was discovered in the 1930s by workers building the Alameda Parkway over the hogback.

Anthony Camera

It’s a courtship not quite as old as the hills, but just as primal as dinosaur sex rituals: the Real Estate Stomp. It involves an amorous developer, bearing promises of jobs and tax revenues and other sweets; smitten and pliant bureaucrats, seemingly just as eager to consummate the arrangement; and a chorus of irate neighbors, open-space advocates, environmentalists, dinosaur fans and others who, while passionate in their own way about Dinosaur Ridge and the area surrounding it, just aren’t in the mood to be wooed.

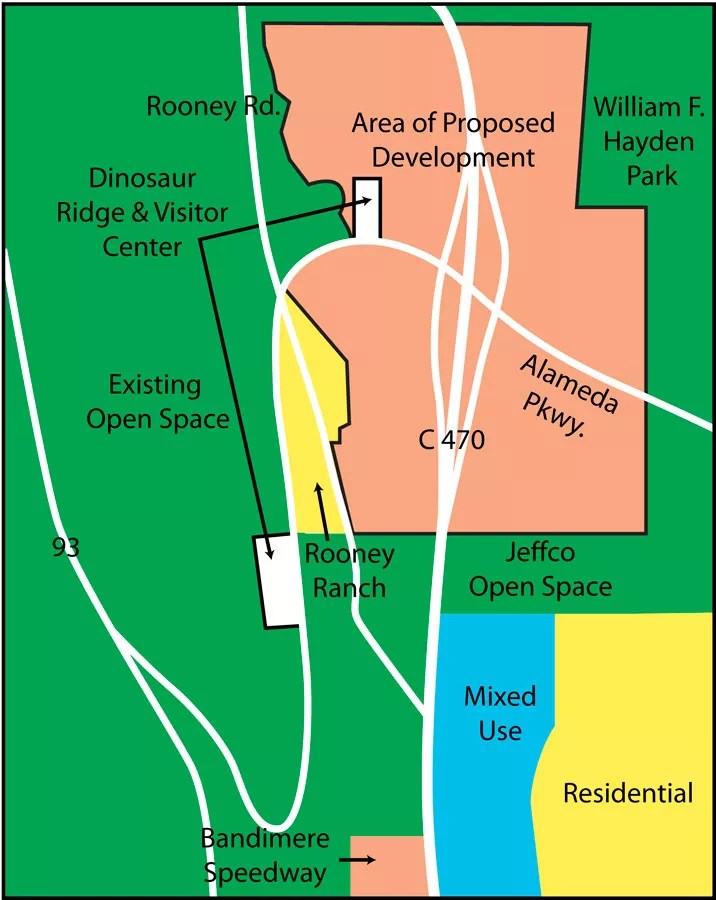

On Tuesday, January 17, Jeffco’s board of county commissioners will consider a proposed zoning change for a planned 140-acre development on four parcels straddling the four corners of the Alameda and C-470 interchange. The change would allow for a proposed hotel and gas station southeast of the interchange and, on the northwest quadrant, up to four car dealerships, which would surround the Dinosaur Ridge visitor center on three sides.

Representatives of the developer, Three Dinos LLC, have described the request as “a minor change” in use for property that’s been zoned for commercial development for nearly a decade. But opponents of the plan say there’s nothing minor about the impacts the development would have on adjoining open-space land, on wildlife, on nearby hiking and biking trails, and on one of the last scenic vistas in the Rooney Valley, which has seen increasing encroachment by highways, the Solterra housing development, a motocross park, Bandimere Speedway and other projects.

The proposal has created deep divisions within the Friends of Dinosaur Ridge. After discussions with the developer, the group’s board voted not to publicly oppose the rezoning in exchange for a pledge from Three Dinos to provide financial assistance that could aid in relocating the visitor center and upgrading its services. But some dissenters in the group, including Lockley, fear that the increased traffic and commercial activity will overwhelm the site and dramatically alter a visitor’s experience.

An aerial view of the interchange property, looking southwest; Dinosaur Ridge is to the left, with the visitor’s center in the foreground.

“It’s going to be a travesty to put car dealerships or warehouses in there,” says Lockley, who resigned from the FDR board last summer. “This is a legacy decision. Jefferson County’s motto is that they’re the Gateway to the Rockies, not Gasoline Alley.”

“It’s absolutely true that the actual tracks will not be impacted by a car dealership,” notes FDR boardmember and geologist Bob Raynolds. “But we’re walking down a path that will be very hard to reverse. We live in Colorado for the beautiful ambience. Why would we destroy it? We chip away at it, and we’re cutting off our own foot, one toe at a time.”

But while the Friends of Dinosaur Ridge have decided to stay neutral on the rezoning question, 42 other opponents showed up at a planning-commission hearing last month to voice concerns of their own. (Other than Three Dinos representatives, only two commenters spoke in favor of the development.) They lamented the effect that bright dealership lights would have on the area’s dark skies and the possible disruption of a long-established raptor migration route. They questioned whether the additional jobs are worth the sacrifice of the last vestiges of a 150-year-old ranch and whether the proposed twenty-foot buffer between the development and existing open space is adequate. And they marveled at the unusual, somewhat circuitous process by which the northwest parcel became slated for development back in 2007, with little public scrutiny or comment and over the objections of the county’s own planning staff.

“Right there is where that valley comes together,” says Eric Brown, a research scientist and president of Dinosaur Ridge Neighbors, the most vocal group opposing the rezoning. “To do large-scale retail there makes no sense. We want to be respectful of the property rights of the Three Dinos, but how we arrived at this situation has been inappropriate from day one. County officials have acted against the recommendations of stakeholders and staff all the way through this deal.”

Brown’s group has launched a website, Save Dino Ridge, and collected 21,000 online signatures opposing the rezoning. But the group has an uphill battle in attempting to thwart a planning process that’s been under way for some time and has the backing of some formidable players. The public face of Three Dinos is Greg Stevinson, developer of the Denver West office park and the Colorado Mills shopping center – and son of the late Chuck Stevinson, who founded an auto-dealership empire now operated by Greg’s brother Kent.

A prominent donor to the campaigns of several county officials and, for seventeen years, the chairman of Jeffco’s Open Space Advisory Committee, Greg Stevinson is widely respected in the western suburbs for his philanthropy and his business acumen. In recent months, he’s put in many hours tinkering with development plans and meeting with FDR boardmembers, Morrison and Lakewood officials and others to try to allay concerns about the rezoning – while cautioning opponents that his group could choose to build an even less desirable mix of fast-food outlets, big-box retail and warehouses under the existing zoning.

“We’re going down a tougher road because we’re trying to do this right,” Stevinson says. “The easy thing would be to say, ‘Screw this. Let’s just go ahead and build – or let someone else build – a shopping center.'”

But to some of the development’s critics, no amount of camouflage or conciliatory design features can hide what they consider an incongruous juxtaposition of fossils and a fossil-fuelish commercial explosion. The dispute, they suggest, says volumes about the county’s emphasis on job creation and commercial development over its natural wonders. They regard the planning decisions that set the process in motion as a failure of imagination, a lost opportunity to make Dinosaur Ridge the centerpiece of something special and unique rather than a bare-bones roadside attraction swarmed by development.

“If you include Red Rocks, this would be the mother of all world heritage sites,” says Lockley. “I’ve looked at dinosaur track sites in many countries, and we really are so far behind the rest of them. This is a world-class site, and you’re making a world-class mistake if you develop it inappropriately.”

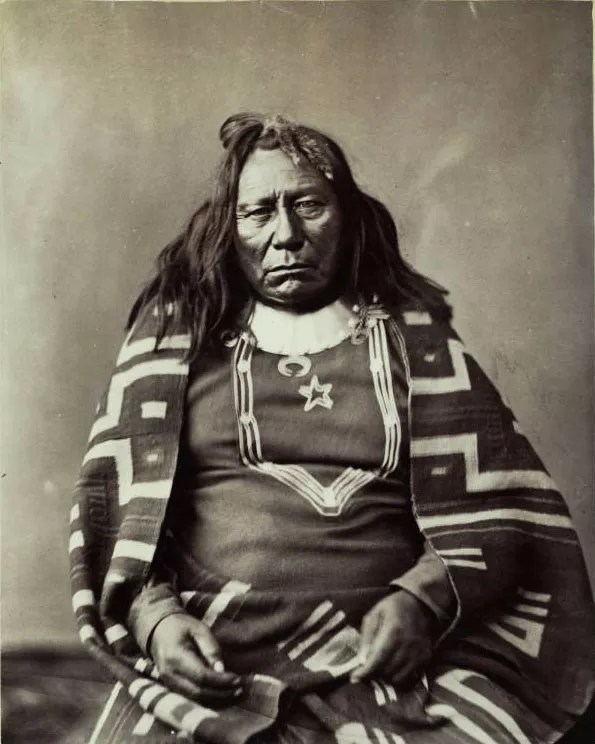

The Rooney ranch, which once spanned 4,500 acres, was homesteaded by Alexander and Emaline Rooney in the 1860s.

Paul Murillo, Library of Congress Archives

In 1859, Alexander Rooney came to Colorado from Iowa in search of gold. He found something better: an unsullied valley spreading out between Green Mountain and the hogback, well supplied with natural springs and buffalo.

Over the next year, Rooney and other members of his family made seven wagon trips back to Colorado. They brought tools, a piano, Rooney’s bride, Emaline, and, eventually, Morgan horses and Galloway cattle. Rooney made a treaty with the Utes and often hosted Chief Colorow, who had designated a large ponderosa pine on the hogback as a place to hold council.

At one point the Rooney Ranch stretched over close to 4,500 acres. But as more settlers arrived, the property dwindled. It was parceled out among subsequent generations, sold piece by piece to pay escalating property taxes, condemned for the C-470 highway. What remains is a small compound of ranch buildings and equipment next to a few cattle and horses on a pasture west of the Alameda-470 interchange – part of the 150 acres purchased by Three Dinos in 2008 for a reported $3.5 million.

“The Rooney family has been really blessed to live in such a remarkable place,” says Rich Rooney, a member of the family’s fifth generation, who grew up on the ranch – and spoke last month at the planning hearing in favor of the rezoning of the property.

“We never thought it would be car dealerships,” Rooney says, “but I don’t fault Greg Stevinson at all. It’s important for the family to back the winning team – and that’s Greg. Jefferson County is going to get more out of a car dealership than a private residence here.”

The acquisition of the land by Three Dinos, as well as the initial rezoning of the property from agricultural to commercial use, was a complicated transaction. Back in 2006, when county officials were first approached about rezoning the area for commercial development, the Rooney family still owned the land. But it was under contract to Terra Norte, an entity whose registered agent is Mary Beth Jenkins, founder of the Laramie Company, a commercial real estate heavyweight. A consultant working for Terra Norte wrote a letter to the Jeffco board of county commissioners, urging it to “consider a county initiated rezoning of the land in order to insure consistency of timing and processing, and a cohesive result.”

The proposed development on all four sides of the Alameda/C-470 interchange would surround the current Dinosaur Ridge visitor center.

Westword

Government-initiated rezoning isn’t all that uncommon; Stevinson points out that the City of Denver has recently taken the lead in upzoning part of the RiNo district in anticipation of future development there. But the rezoning of the Rooney parcel was actually triggered by a request from the potential developer, and the board of county commissioners was happy to oblige. Terra Norte didn’t have to go through the usual application process and fees. Only eight citizens and one representative of a brick company in the area attended the 2006 community hearing on the county-initiated rezoning. On one planning document, the level of community interest in the proposal was deemed “low.” The same document declared that the issues raised by the proposal were “none.”

Not everyone in county planning agreed with that assessment, however. A draft document, prepared by planning staff but never signed, points out that land-use guidelines for the C-470 corridor sought to discourage “big-box retail” and encourage office and light industrial use. The area also included “visually sensitive areas” that would be difficult to protect under the county’s medium-scale retail zoning. The document concluded that the “proposed rezoning is not compatible with existing land uses.”

But that draft was deep-sixed. The version that was submitted to the planning commission, authored by Jeffco’s development and transportation director, heartily recommended that the rezoning be approved. It stated that Jeffco’s leaders “have the unique opportunity to promote advancement of economic development, which may not necessarily comply with all aspects of our land use plans.” It also stressed that the Jefferson County Economic Development Council (JCEDC) – a private entity that receives generous financial support from county coffers, counts a substantial roster of the region’s elected officials and business leaders among its members and has played a significant role in shaping county land-use policies – was keen on seeing the parcel become a kind of “Tech Center West.”

“This is a legacy decision. Jefferson County’s motto is that they’re the Gateway to the Rockies, not Gasoline Alley.”

Yet the planning commission still had reservations. It approved the rezoning in three quadrants, but not in the northwest parcel, the one surrounding the Dinosaur Ridge visitor center, regarding that parcel as “necessary for backdrop protection.” But that exception was soon overruled by the three county commissioners, who unanimously granted Terra Norte exactly what it had asked for. A few months after the zoning change, Mary Beth and Bill Jenkins joined with Stevinson and his longtime friend John Mullins, a former director of Colorado’s Office of Business Development, to form Three Dinos and complete the purchase of the land.

Stevinson says that he and the other principals had been “looking for some opportunities in the area” and thought the parcel at the interchange was perfect; it was an “obvious commercial node” that could support retail, light manufacturing and possibly even a tech center. The county was willing to initiate the rezoning, he adds, because the buyers’ vision fit in with the kind of job creation the then-county commissioners were seeking to promote.

“They wanted jobs and tax-generating activity,” he observes. “Their argument was – and I have to agree with it – you build a full diamond interchange, it should be generating jobs and a tax base. It shouldn’t be open space, and it shouldn’t be residential.”

At the time, Commissioner Kevin McCasky had declared that the creation of “primary jobs” was a top priority, since one out of every three members of Jeffco’s workforce commuted to jobs outside the county. Whatever the merits of McCasky’s plan, the ease with which the board of county commissioners could ignore land-use provisions and staff recommendations in pursuit of their own agendas is startling. Critics of county government have long lamented the degree to which power in Jeffco, which has a population of more than half a million, is concentrated among just three elected officials. Arapahoe and Adams counties, for example, each have five commissioners.

“When you’ve got a county with a population larger than Wyoming’s and it’s run by three people, you only need two of them to run everything,” notes Mike Zinna, a gadfly and radio host who frequently locked horns with the McCasky board and now lives in California. “That’s the way it works in Jefferson County.”

Paleontologist Martin Lockley, who

Anthony Camera

Zinna believes the county’s approach to growth issues is highly influenced by the economic development council, now known as the Jefferson County Economic Development Corporation, which is “allowed to operate in the shadows without any oversight. It allows the commissioners to do a lot of recon and deal-making without having to call a public board meeting.”

Stevinson is a former member of the JCEDC but says he hasn’t been actively involved in the organization for decades. Still, during his forty years in real estate, he’s forged relationships with just about everybody who matters in county eco-devo circles. “You can trace so many of the land deals that get done in that county back to people who are connected to Stevinson,” Zinna insists. “This guy is so wired in.”

Two of the three commissioners who approved the 2007 rezoning later left office under a cloud of litigation or ethics investigations. In 2011, McCasky resigned midway through his second term to take the job of executive director of the JCEDC, shortly after voting to increase the county’s annual payments to the organization to $400,000. The Colorado Independent Ethics Commission later found that McCasky had violated the rules of conduct for government employees by failing to disclose the obvious conflict of interest, but no penalty was imposed. McCasky left the JCEDC in a restructuring last spring.

The other commissioner, Jim Congrove, ended up as the defendant in a civil-rights lawsuit filed by Zinna, who claimed that county officials (and Congrove in particular) had harassed him, put defamatory material about him on an anonymous website, hacked into his e-mails, and otherwise tried to thwart his investigations of the commissioners’ back-room wheeling and dealing. Congrove died in 2012; Zinna is still trying to collect $500,000 in legal fees after a federal appeals court ruled that he was entitled to more than the trial judge was willing to award him.

Three Dinos partner Greg Stevinson (right), seen here testifying before county planning officials last month, says his company is trying to develop the property

Congrove’s and McCasky’s travails had nothing to do with the Three Dinos project, but that deal took some strange turns of its own. Six months after the land was rezoned from agricultural to commercial, the commissioners approved a $6 million loan to the just-formed Green Tree Metro District to help fund construction of the Alameda-470 interchange. At the time, the three board members of Green Tree were all principals of Three Dinos: Stevinson, Mullins and Bill Jenkins. Additional funding for the interchange was provided by Carma, the developer that owned the Solterra housing development.

One longstanding condition of the interchange construction was that Alameda would then be closed to vehicles over the hogback, in order to protect Dinosaur Ridge. But only months after Three Dinos purchased the Rooney property, the company filed a lawsuit against Denver and Jefferson County, asserting that since the road over the hogback had been “abandoned,” rights to the road now belonged to Three Dinos, under a reversion clause in a deed signed by Otis Rooney in 1936, granting the original Alameda right-of-way.

The lawsuit went to mediation. Three Dinos eventually gave up its claims, but not without some recompense. The county paid $1.4 million to purchase nineteen acres from the company for open space – a price some observers considered inflated, but the county had already increased the value of the land by rezoning it. Three Dinos also acquired in the settlement a hunk of the Alameda right-of-way just west of the interchange, ensuring that the road couldn’t be expanded. The deal led to a showdown between the county commissioners and county administrator Jim Moore, who criticized the open-space purchase and refused to put the item on a consent agenda. Fired shortly thereafter, Moore later settled his own wrongful-termination lawsuit against the county for $175,000.

Stevinson describes the litigation over the road as a “friendly quiet title suit.” “I’d never sued anybody in my life,” he says. “But our concern was, if we start to sell this property, the reverter clause could transfer to somebody else. We weren’t in it for the money. It was purely to determine who owned it.”

In 2011, another controversy erupted over the commissioners’ decision to grant a ten-year extension for repayment of the $6 million loan to the Green Tree Metro District. An article in the High Timber Times noted that Green Tree boardmembers Stevinson, Mullins and Jenkins had all made campaign contributions in the past to commissioners McCasky and Faye Griffin. (Records indicate that between 2006 and 2014, Stevinson alone contributed $34,000 to the campaign funds of four commissioners, including $4,000 to Griffin’s 2006 campaign for county treasurer.) McCasky, who’d received $9,000 from the trio, told the newspaper that he was in favor of canceling the loan altogether, viewing it as an “economic investment” in the area.

The main reason for the loan extension was that nothing had yet been built on the property, nothing that would generate fees to repay the loan. Over the years, Stevinson says, Three Dinos was approached by various people proposing oddball projects for the property, including a velodrome, an outdoor entertainment venue, a dinosaur-oriented theme park, and even a possible relocation of the National Western Stock Show and the Jefferson County fairgrounds. But none of the pitchmen had figured out how to finance needed infrastructure and bring a water supply to the area.

“There was no water out there at the time,” Stevinson says. “We knew it was coming. It was a question of when.”

The water came, and became more affordable, as the Solterra development began to fill in. Three Dinos began exploring a range of options for each of the four parcels: warehouses, retail, possibly even some apartments. Over many months, there were several discussions with Harley-Davidson, a potential anchor tenant, but the company decided on another location. The idea of several car dealerships to anchor the development – none of them owned by the Stevinson family, by the way – began to look like a real possibility.

The move would require another change to the zoning of the property. But by this point, the county had demonstrated its commitment to getting something built at the interchange many times over.

Dinosaur Ridge Neighbors, a group opposed to the rezoning at the interchange, turned out in force at last month’s Jefferson County planning commission hearing.

Anthony Camera

Where some see doom, others see potential. Friends of Dinosaur Ridge board president Kermit Shields sees the development descending on the land around the visitor center as an opportunity to start planning for a better visitor center – one closer to the track site, one that could offer visitors a better experience than the current cramped parking and pit toilets.

“My personal opinion is that if we stayed at the current site, we’d be pretty much strangled there,” Shields says. “If we could preserve that whole valley and not have any development there, that would be great. But we don’t have many options right now. We’re trying to make the best of it. [Jeffco] Open Space and Three Dinos are cooperating with us, and I think we’re going to come up with a solution in the end that’s going to be good for all of us.”

The land the visitor center sits on is owned by Jeffco Open Space; the Friends operate there under a lease agreement that expires in 2018. Tom Hoby, the director of JCOS, has proposed moving the center to other open-space land along Rooney Road, closer to the track site. The old 1.5-acre site would be turned over to Three Dinos, which would donate three acres from a corner of its southwest parcel for visitor center parking. It’s part of a larger strategy Hoby hopes to implement that would preserve open space west of a gulch that runs north-south through the Rooney property, providing a buffer zone that would help protect the track site and the location of Chief Colorow’s tree.

Born a Comanche, Chief Colorow was adopted and raised by the Muwache Utes.

W.G. Chamberlain, Denver Library Western History Collection

“Right now that particular property west of the gulch is owned by Three Dinos, and they have some plans for flex office space,” Hoby says. “If that occurs, that’s really challenging for the Dinosaur Ridge visitor center, for the tree, for park visitation in general. We want to try to acquire what’s left of Rooney Gulch.”

Hoby’s agency doesn’t have the resources or the inclination to try to purchase the whole northwest parcel; under its current commercial zoning, Hoby figures that land is worth close to ten times what Three Dinos paid for it nine years ago. “For forty acres, we’d be doing our best negotiating to get it for $9 million,” he says.

At last month’s planning hearing, Hoby pointed out that his agency doesn’t pursue commercially zoned property. More than a third of its $33 million annual budget goes to debt service, paying off a bond-financed purchasing spree from fifteen years ago. “We’re very careful and strategic about how we spend open-space funds,” he told the planning commission.

Stevinson has praised Hoby’s proposal as a “creative idea.” For its part, Three Dinos has offered to donate $175,000 to the Friends of Dinosaur Ridge for every car dealership that opens. The money provided wouldn’t be enough to open a new visitor center, but Stevinson has pledged to help the group with fundraising as well as “seed money.”

Lockley estimates that it might cost around $10 million to build a proper visitor center and add structures to protect the tracks from vandalism and erosion. He suspects the FDR board was under some pressure, with its lease in the balance, to endorse Hoby’s plan and reach an accommodation with the developer. “That’s not the way it’s supposed to work,” he says. “The county should be neutral.”

Hoby denies issuing any ultimatums to the board. “We’ve talked to them about, ‘Hey, this is an opportunity – but it’s up to you,'” he says. “I wasn’t telling them anything they didn’t already know.”

Of course, the Friends of Dinosaur Ridge are not the only interested party that the developer is seeking to appease. After the planning hearing, Morrison town administrator Kara Zabilansky filed a written objection to the rezoning, noting that the proposal still included plans for a grocery store – when, weeks earlier, Stevinson had “specifically confirmed” to Morrison’s board of trustees that Three Dinos would take the store out of the application rather than compete with Morrison’s own development plans in the Rooney Valley.

“This idea of having some sort of pastoral, visionary gateway — that horse left the barn a long, long time ago.”

Stevinson says the company is now seeking a “boutique grocery store” for the southeast parcel. “We have been approached by large national grocery stores that want to come here,” he says. “We have, out of deference to Morrison, made that our last choice.”

Three Dinos is also promising boutique car dealerships. The notion strikes some of the opponents as absurd, given car lots’ reputation for harsh lighting, tacky displays and streamers, noisy service bays and loudspeakers, all on what is essentially a sprawling parking lot. But Stevinson can enumerate a dozen reasons that dealerships are preferable to other forms of development that Three Dinos could plant in the same spot. They draw less traffic than fast-food drive-thrus, fewer trucks than warehouses. The lights can be mostly shut off at ten at night, while distribution centers might run around the clock. The developer can dictate what routes must be followed when customers are taken out on test drives, minimizing neighborhood impact. The jobs might not be “primary jobs,” as the JCEDC defines them, but they’re higher-paying than what you get with most retail.

Stevinson acknowledges that many people who bike the trails, hike Dinosaur Ridge or take in the view from Solterra have been accustomed to thinking of the area as open space, or pasturage, or something else that it isn’t. “The concerns I hear, about how people like the cows and the pasture, are the same things I heard when Solterra was being built,” he says. “The whole area isn’t some sort of pristine open space. You’ve got the motorcycle park, the clay pits, Bandimere and 4,000 more homes coming in right across the street. This idea of having some sort of pastoral, visionary gateway – that horse left the barn a long, long time ago. This is on a full diamond interchange, with an intent all along to build a commercial tax base. We’re trying to do this with the least impact we can.”

Eric Brown (left) and Randy Stafford of Dinosaur Ridge Neighbors question the role pro-growth forces in county government played in designating the area for commercial use.

Anthony Camera

He points out that his Denver West development generates $2 million a year for Jeffco Open Space. “I’m pretty damn proud of it,” he says. “We generate twelve to fifteen thousand jobs. If we can keep employment opportunities closer to home, people travel less. There has to be an economic component to open space. You have to find areas to generate the base you need to preserve and protect.”

Jefferson County’s planning commission thinks so, too. After listening to hours of public comment on the Three Dinos application – almost all of it negative – the panel voted 5-2 to approve the rezoning request, sending it on to the county commissioners for a final review. Several members cited Stevinson’s participation in the deal as a significant factor in their decision.

“I’m feeling good about who we have in front of us,” stated commissioner Dawn Moore. “If it was anybody else, it could be a harder fight.”

“It would be very easy to be swayed by the history and the personality of the applicant,” added chairman Tim Rogers. “I’m comfortable with what the applicant is proposing. At the end of the day, I think it’s the right decision for the community.”

Eric Brown of Dinosaur Ridge Neighbors points out that the five members of the group who voted for the rezoning all work for real estate or property management companies, energy firms or other pro-growth forces in the county. The two dissenting votes came from a retired IRS investigator and a hydrologist. The composition of the board is one example of what Brown sees as a drastic imbalance in favor of development throughout the higher echelons of Jefferson County government. Members of his group have been talking to other citizen groups about possible court appeals or recall campaigns.

“There seem to be some very inappropriate relationships and conflicts of interest here,” he says. “If this gets approved, we believe we have strong grounds for appeal – not necessarily on land use, but in administrative law. There’s grounds for going after the county commissioners for not doing their duty as public trustees.”

In preparation for next week’s vote by the county commissioners, members of Brown’s group have spent hours familiarizing themselves with land-use plans. One, software architect Randy Stafford, has made several trips to Golden’s Taj Mahal, digging out files from archives, poring over handwritten notes, discarded drafts, letters of intent – trying to trace how elaborately crafted documents espousing the protection of heritage and historic sites, natural features and precious viewsheds all seemed to be supplanted, with just a wave of a pen, in favor of commercial interests.

Stafford is a second-generation Jefferson County native. He grew up near Kipling and Quincy in the 1960s, in what was then the westernmost neighborhood in the metro area. Beyond his street were a lake, cows, fields of wheat stretching to the hogback. He was a young man when Governor Richard Lamm made his infamous vow to put a “silver stake” in the plan for a highway called 470 around the southwestern edge of the metroplex, recognizing that beltways didn’t contain sprawl but hurled it ever outward.

Lamm relented. The beltway arrived, along with the steady march of subdivisions. Stafford and his wife rode bikes in the Rooney Valley and figured it was too far from services to be ruined, even as the developments crept closer.

Alexander Rooney’s grandson Alex built a picnic area beside the Colorow Tree, where the Ute chief held council.

Paul Murillo, Library of Congress Archives

Recently Stafford hiked up to the Colorow Tree, the 400-year-old ponderosa pine that the big chief used as a place of reflection and parlay. He had never been there before and found the view astonishing: the city, the plains, Green Mountain, Soda Lakes to the south. The tree had arrived long after the last Allosaurus had devoured the last Stegosaurus in the neighborhood. Yet the Colorow Tree had outlived so many creatures, tribes, explorers, speculators that had come to the valley since.

“It was interesting to me that a Native American chief selected that site,” Stafford says. “I’m not a terribly sentimental individual, but to me, it’s kind of a spiritual site. It’s a link to what used to be here before we got here. It’s also a good place to reflect on what’s happening here, the different values of the people involved.”

The longer Stafford stayed by the tree, the more he found the view troubling. “We’ve got a lot of people who just want to develop commerce on the land and don’t appreciate the historical and scenic value,” he says. “It’s worth fighting for the conservation of the land.”