Maggie Holland

Audio By Carbonatix

D’Evelyn High School senior Maggie Holland just won a Boettcher Scholarship to study environmental engineering at the University of Colorado Boulder. She says she was inspired by her time at Bear Creek Lake Park – and her work to save it.

Holland calls Bear Creek Lake Park the heartbeat of Lakewood; she’s there almost every day. Since she was hit by a car in sixth grade, she’s used the park as a safe place to longboard, bike and run. She recently completed her first marathon at Bear Creek Lake Park.

On one of her runs, Holland learned that the park could be at risk. After spotting a “Save Bear Creek Lake Park” sign, she went online and added her name to the Save Bear Creek Lake Park email list; she told founder Katie Gill that she was willing to help in other ways, too.

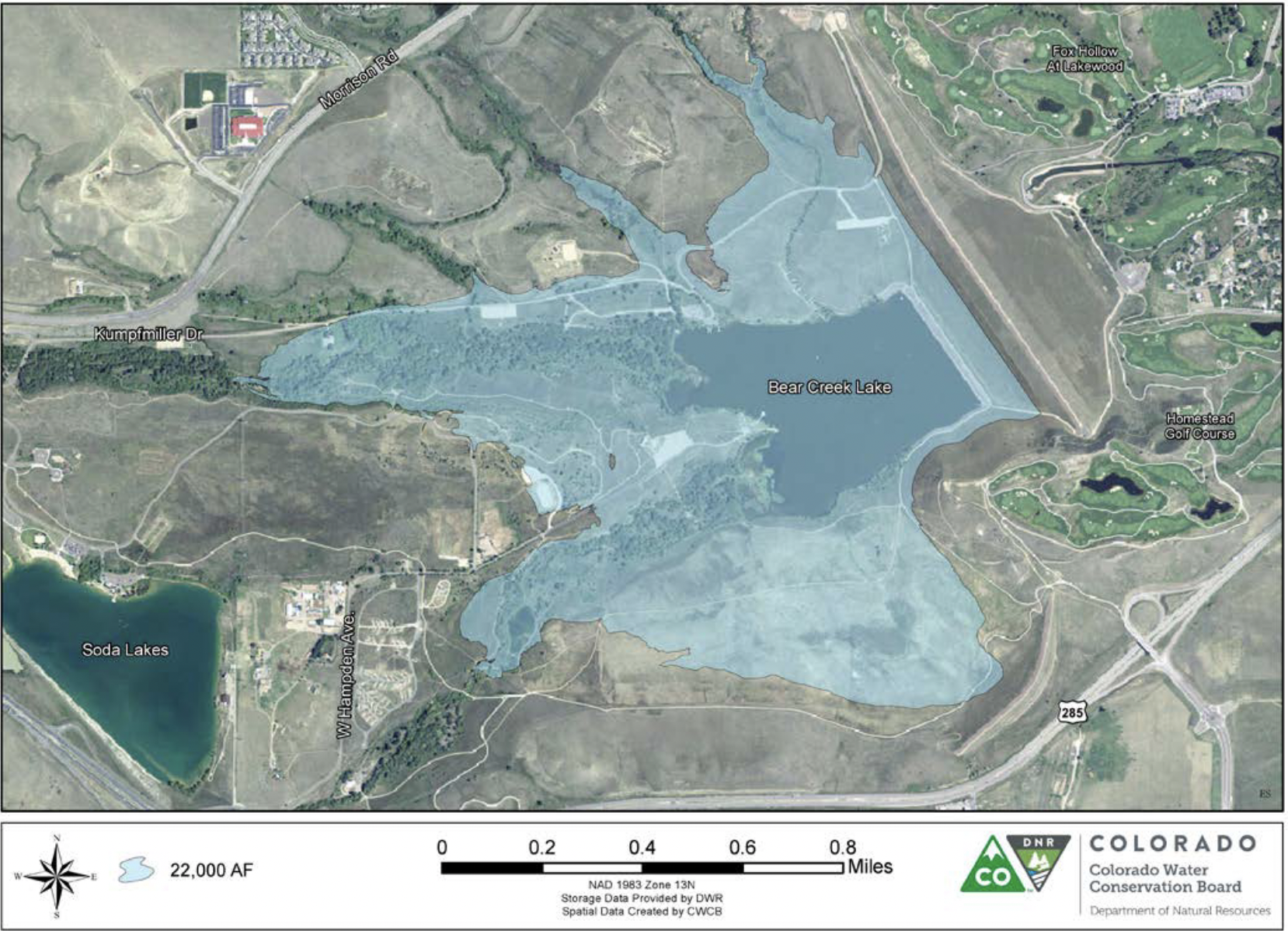

Gill, a member of the Morrison town board, does her work with Save Bear Creek Lake Park as a private citizen. She started the organization in 2019 after she saw what she thought was a typo in a newsletter from the Bear Creek Watershed Association, saying there had been a suggestion to increase the maximum storage volume of Bear Creek Lake from 2,000 acre-feet to 22,000 acre-feet. But the number was no typo, and that concerned Gill, because increasing the volume of the lake would reduce the area of the park devoted to animal and plant habitat and human recreation.

“It was originally built for flood protection, and in the interim, it’s become this place which so many people enjoy as a park,” Gill says. “Bear Creek flows into the park from the west, and Turkey Creek flows in from the southwest, and if they were to put another 20,000 acre-feet of water into that reservoir, it would inundate over a mile of Bear Creek and all of that habitat.”

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is currently working with the Colorado Water Conservation Board to study whether water storage can be added to the park’s purpose.

The plan would increase the lake’s size.

Colorado Water Conservation Board

Bear Creek Lake is part of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Tri-Lakes Project that also encompasses the Cherry Creek and Chatfield dams and lakes; the original goal of the project was flood control. The dam at Bear Creek was completed in 1982. That same year, the City of Lakewood established Bear Creek Lake Park, leasing the land from the federal government. In contrast, Cherry Creek and Chatfield are both state parks.

“I’ve heard some people say, ‘Well, let’s have another Chatfield,'” Gill says, noting that Bear Creek Lake can’t support motor boats and Chatfield’s level of lake recreation because it simply isn’t big enough. “The other big problem with this, which really separates it from Chatfield, is there would be significant fluctuations in the pool level,” she adds. “There’s not enough supply in Bear Creek to fill it up to a large new level all the time.”

Through Save Bear Creek Lake Park, Gill has gathered supporters who are now asking the Army Corps of Engineers to consider alternative ways to increase water storage in the state without flooding the park. Gill says the organization’s mailing list has over 700 names; 120 people attended the Lakewood City Council meeting on March 28 to urge the city to protect the park.

Maggie Holland says Bear Creek Lake Park is her safe place to longboard.

Maggie Holland

At its April 26 meeting, the Lakewood City Council responded, issuing its first live proclamation since 2020. According to the Proclamation Supporting Save Bear Creek Lake Park, “Substantial weight will be given to the alternatives identified by Save Bear Creek Lake Park that will provide the same level of water storage to the State but would have significantly reduced impacts on both the people who reside within the area served by Bear Creek Lake Park and those who come from beyond that area to use this beautiful park, as well as all of the animals and creatures that call this park home.”

Every member of the council approved the proclamation. Councilwoman Sophia Mayott-Guerrero noted that even though her ward doesn’t border the park, her constituents have all said they support keeping it as is.

Gill sees the Lakewood proclamation as a signal to other entities, especially the Army Corps of Engineers, that they need to take people’s concerns seriously. While the Army Corps of Engineers did not respond to a request for comment, the Colorado Water Conservation Board sent a statement through Marketing and Communications Director Sara Leonard.

“The Colorado Water Conservation Board values its partnership with the City of Lakewood and looks forward to continuing to work with the City as the Bear Creek Lake Reallocation Feasibility Study continues,” it says. “It is important to remember that this is just a feasibility study, and does not guarantee that a storage project will be approved. As is part of any feasibility study that uses CWCB funding, determining the environmental and social impacts of any potential project is a critical element to determining if it is worthwhile and multi-beneficial for the local community.”

Identified alternatives include making the lake deeper rather than wider and creating a second lake elsewhere in the park.

“The estimated supply-demand gap for water for residents in the area that the Bear Creek Lake Park reservoir would reach by the year 2050 is estimated to be about 400,000 acre-feet of water,” Holland says. “The expansion that we’re talking about…would only count for 20,000 acre-feet, which is about 3 percent of the overall water storage. To put it in the vernacular, the juice ain’t worth the squeeze.”

Holland is pushing for a long-term plan that preserves the park for city-dwelling nature lovers. Not everyone can afford to get to the mountains, she notes, and Bear Creek Lake Park makes nature more accessible to families of different financial backgrounds.

Liam Hopkins, a Green Mountain High School student, agrees. A Colorado reptile enthusiast, he points out that the diversity of animals at the park is a rare asset, especially so close to a large metro area. Park rangers once gave him permission to enter the park after hours; he and his friends spotted seventeen tiger salamanders, the Colorado state amphibian. He’s also seen owls and rare snakes like the Western milk snake, which he describes as the “Holy Grail of Bear Creek.”

“I couldn’t imagine life without having [the park] there,” he says.

Maggie Holland and her family are Bear Creek Lake Park regulars.

Maggie Holland

Hopkins and Holland have worked together to advocate for alternatives to flooding the park, and both spoke before Lakewood City Council last month.

“Having that young voice there to show that this park matters to the young people, this park matters to the future generations to come, I think is a really, really important part of the project,” says Hopkins.

They won’t be as young by the time they know the fate of their beloved park: According to a feasibility study memo, any decision on Bear Creek Lake could be two years away.