Bennito L. Kelty

Audio By Carbonatix

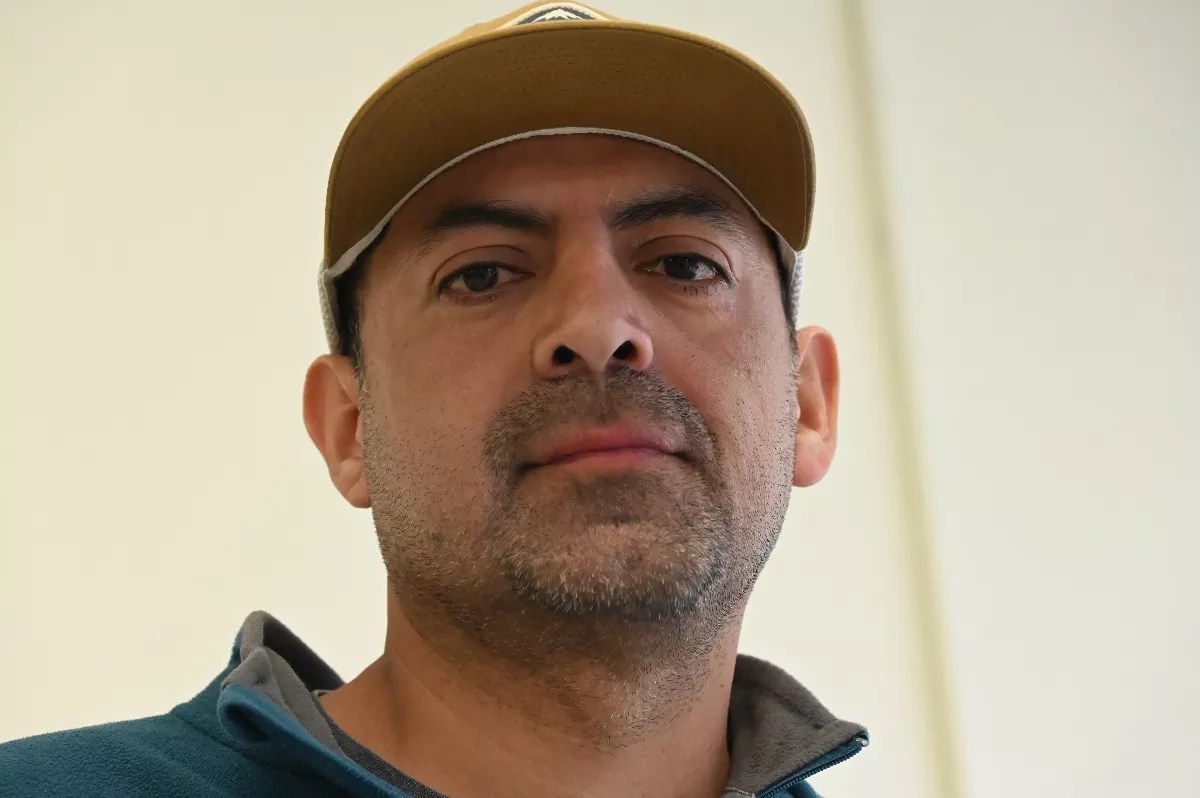

A native Spanish speaker, Mateos Alvarez can usually help the migrants and day laborers who come to the Dayton Day Labor Center looking for work. It’s been located at 1521 Dayton Street in northwest Aurora for close to a decade, and during that time has drawn Mexican men “and a sprinkling of Central Americans,” says Alvarez, who runs the center.

“I’ve always been able to know what’s going on with them and get involved, because even if they don’t speak English, they speak Spanish,” says Alvarez, who also heads the Aurora Migrant Response Network. “That’s never been an issue.”

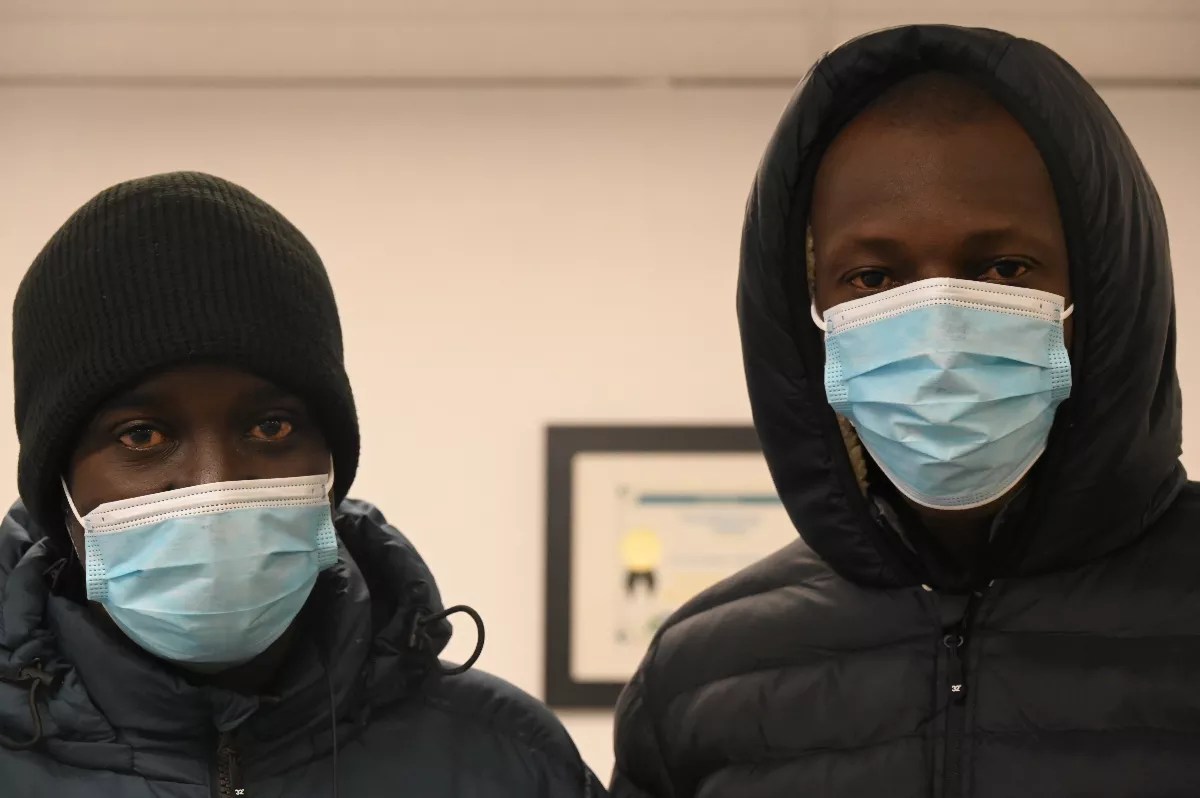

But even as metro Denver has been dealing with a large influx of Venezuelans and some Colombians over the past fifteen months, thousands of Mauritanians started arriving last spring as well…and most of them headed straight to Aurora. At first, Alvarez had no idea where these migrants had come from.

“I’m not talking a sprinkling. I’m talking hundreds of Mauritanians were standing outside our door here. We had no clue what language they spoke,” recalls Alvarez. “We tried to speak Spanish. And all we heard was Pulaar, Pulaar, Pulaar.”

Between four and six million people speak Pulaar, mostly in Mauritania and Senegal. Alvarez doesn’t. Struggling to understand the new arrivals, Alvarez finally went to Project Worthmore, a nearby nonprofit that’s part of the Migrant Response Network, to find an interpreter. That’s who told Alvarez that these migrants were from Mauritania, a country on the northwestern coast of Africa that sits by Arabic-speaking countries like Algeria and the disputed territory of Western Sahara, as well as the French-speaking countries of Senegal and Mali.

None of the migrants spoke Arabic, the official language of Mauritania, but a few spoke French. Some spoke Wolof. And they kept coming, says Alvarez, who estimates the number by now at upwards of 8,000.

Mamadou Dia, the owner of the Dia International Market, is from Mauritania and has been living in Aurora for almost 24 years; he’s seen the recent flood of Mauritanian migrants. “Most of them come here seeking help, and I try to help them because they’re my fellow citizens,” Dia says.”The only thing we can do is help each other, and I’m doing the best I can, from finding them lawyers or work.”

Dia says the Mauritanians are leaving their country because “it’s very one-sided there.” The majority of the country’s residents are Black Mauritanians, who speak Pulaar or Wolof but not Arabic, and they “are minimized” and not given the same opportunities as Arab Mauritanians,” he adds.

“It’s been happening for many, many, many years,” Dia says. “Everybody who follows the news and what’s going on around the world knows what’s going on in Mauritania.”

Mateos Alvarez leads both the Denver Day Labor Center and the Aurora Migrant Response Network.

Bennito L. Kelty

Through the interpreter, some Mauritanian migrants told Alvarez that they were escaping government repression. “From what they explain to me, it’s just that the current government is being repressive against them, retaliatory for not supporting the government,” Alvarez says. “A lot of them have stated that they were targeted, and a lot of family friends were concerned for their safety and asked them to leave the country because their life is in danger.”

The Mauritanians who have shown up in Aurora are all non-Arab, as far as Alvarez can tell, and they’re all devoted Muslims. “They all are very dedicated. They go to mosque every Friday,” he says. “They pray. They ask me if they can come in and pray in the corner there or do it outside in the alleyway, but they are very dedicated, very committed.”

While many mention political repression, other Mauritanian migrants have told Alvarez they’re fleeing slavery.

“They say ‘slavery,’ and I don’t know if they mean indentured servant or they’re working for others for very little or no pay over long periods of time,” Alvarez says. In 1981, Mauritania became the last country in the world to abolish slavery, and it wasn’t criminalized until 2007. But the U.S. State Department reported in 2021 that “slavery continues to affect a small, but not insignificant, portion of the country’s population in both rural and urban settings,” including Wolof communities.

Dia has no doubt that slavery is continuing in Mauritania.

“It is still, still, even if the refugees don’t acknowledge it, everybody knows what’s happening in Mauritania,” Dia says. “It’s real slavery. If you watch or read, you’ll see what’s happening there. Even these [migrants], if they’re not educated, they understand what’s going on there.”

Before Alvarez found an interpreter, he thought that the Mauritanians were coming from Venezuela along with other migrants fleeing economic collapse there. Instead, he learned that they’d left their native Mauritania and flown into Nicaragua, where they joined the Venezuelans and Colombians heading north. When they arrived in Texas, the Mauritanians even rode on buses with the Latin American migrants to Denver, but then skipped the Mile High City and went to Aurora.

“They followed the Spanish-speaking migrants and walked from Central America, up into Mexico and into the United States and, for some reason, to northwest Aurora,” Alvarez says. “What makes the Mauritanians different is they bypassed Denver altogether.”

Alvarez isn’t sure why they came to Aurora, but “a few of them got here and moved way out to Denver and didn’t have money and they didn’t like it in Denver and said, ‘Nobody looks like us,'” Alvarez says. But Aurora had a small Mauritanian community and a few Mauritanian stores, so it offers “a cultural connection that makes the Mauritanians feel comfortable,” he adds.

The Mauritanians come to Aurora because “everybody is going to follow somebody,” says Dia, who’s housing some of the migrants.

Before the 2023 influx, the U.S. government estimated that 8,000 foreign-born Mauritanians were living in the entire country, 3,000 of them in Ohio. But then racial tension flared in Mauritania in May after a Black man, Omar Diop, died in police custody.

On August 19, an Associated Press story reported that upwards of 8,500 Mauritanians had crossed the border from Mexico between March and June, with many learning about a route through Nicaragua via videos on TikTok and other social media. “The influx of Mauritanians has surprised officials in the U.S. It came without a triggering event – such as a natural disaster, coup or sudden economic collapse,” reports the AP. “Some who left say they’re again fleeing state violence directed against Black Mauritanians.”

More than 38,000 migrants have arrived in Denver since December 2022, mostly from Venezuela. According to Jon Ewing, spokesperson for the Denver Department of Human Services, Mauritanians are “not in our shelter system. … I have heard of the large number in Aurora.”

Ryan Luby, spokesperson for the City of Aurora, says, “We don’t have a mechanism to gather information” regarding the number of migrants now coming to Aurora, or their nationalities. Aurora has a reputation as a diverse place, calling itself the “World in a City.”

About 20 percent of its population of just under 400,000 is foreign-born, and it’s home to about 14,000 African immigrants, with almost half coming from the East African countries of Ethiopia and Eritrea and about 3,000 coming from West Africa, according to the U.S. Census. But that was before the recent flood of Mauritanians.

In October, the Migrant Response Network hired a French-speaking manager; through her, Alvarez has been able to communicate with the migrants who speak Pulaar. “When one only speaks Pulaar, through the network, in French, they locate one who speaks both English and Pulaar or French and Pulaar and they help each other out,” Alvarez says. As a result, the Mauritanians now know they’re welcome at the Dayton Day Labor Center.

“They learned about me and what this building was about,” Alvarez says. “That’s why they make this one of their refuges, because when we were able to communicate, we as our organization said, ‘You are welcome here and this is a safe space, and if you need anything, you make sure you connect with us.'” So far, though, he hasn’t been able to connect them with jobs.

Black Mauritanians who come here “deserve to work,” says Dia, adding that he hopes they earn Temporary Protected Status, a federal designation that allows immigrants who arrived in the U.S at certain times – including Venezuelans who got here before August – to work in this country.

“If they get TPS or work authorization, they can stand on their feet and help themselves, and they can contribute to this country,” Dia says. “I’m sure if they get help, they’re going to be very helpful to us in this country.”