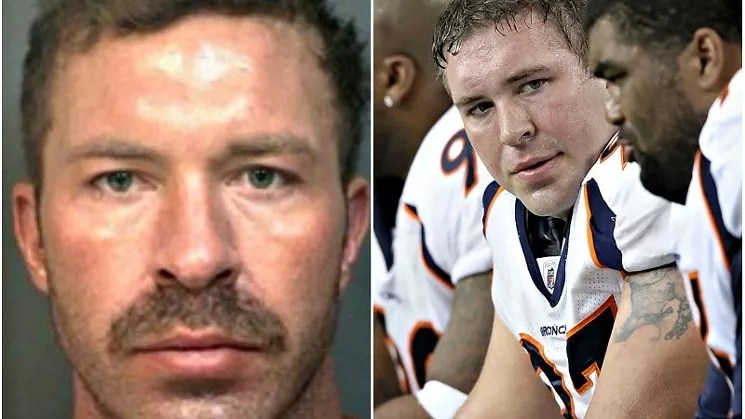

Boulder Police Department/Christian Petersen via Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

Millions of people across the country are excited to watch the Super Bowl match-up between the Kansas City Chiefs and the San Francisco 49ers on Sunday, February 2. But former NFL quarterback and Castle Rock resident Mike Boryla is focused on an event twelve days later: the February 14 arraignment of Justin Bannan, a CU Buffs alum and ex-Bronco with a history of concussions. Bannan was arrested last October for shooting and wounding a woman in Boulder while under the delusion that he was being chased by members of the Russian mafia.

In addition to being an attorney, author and playwright, Boryla, who’s in his late sixties, has become one of the nation’s most energetic critics of the National Football League and what he sees as its lip service when it comes to brain injuries. “It’s clear to me that NFL football cannot be played safely,” he says. “It cannot be done.”

He sees Bannan as a tragic case in point. En route to the police station after being taken into custody last fall, the former player reportedly told officers that he suffers from hydrocephalus, defined by the Alzheimer’s Association as “a brain disorder in which excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) accumulates in the brain’s ventricles, causing thinking and reasoning problems, difficulty walking, and loss of bladder control.” And during a December hearing at which a judge upheld attempted murder charges against him, Bannan’s attorney, Harvey Steinberg, telegraphed his likely defense by way of this rhetorical question: “It’s not relevant that he may have had 25 concussions during the course of his career and may suffer from CTE?”

Many former football players have been diagnosed with CTE, or Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a condition associated with concussions and repeated blows to the head, and onetime CU Buffs haven’t been excluded from the lengthening roster of victims. Recall that Heisman Trophy winner Rahsaan Salaam died by suicide in a Boulder park circa 2016. His brain wasn’t tested for CTE after his death, but his family believes that damage to this organ by the disease contributed to his fatal act. When his Heisman was auctioned off in 2018, a portion of the proceeds went to CTE research.

Boryla was on NFL rosters for only a handful of seasons; he was drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles in 1974 and retired as a member of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 1978. “The Lord just told me to quit, even though I didn’t know how dangerous it was. None of us did,” he recalls. “And if I hadn’t made that decision, I’d probably be dead. I’d already had three concussions. If I’d played another five years and had three or four more, it wouldn’t have been pretty.”

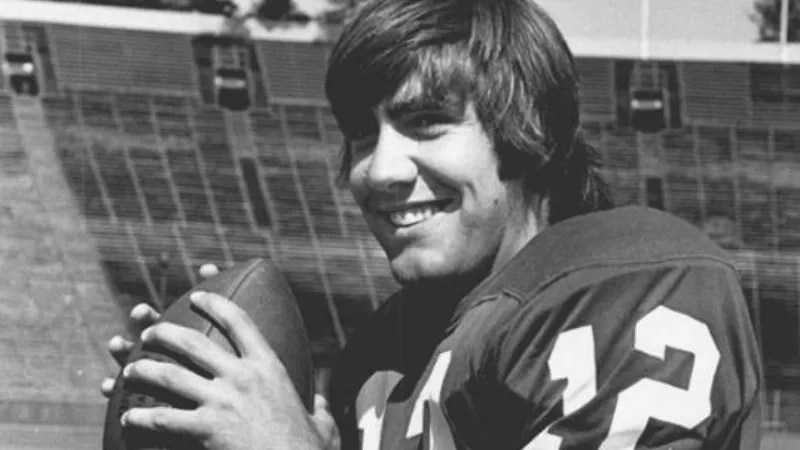

Mike Boryla during his years playing quarterback for Stanford University.

Courtesy of Mike Boryla

Boryla began playing football in Denver as a third-grader, and he became a local hero as a signal caller for Regis High School. In 1968 he won a Denver Post Gold Helmet Award as Colorado’s outstanding senior gridiron performer and was, in his words, “probably the most highly publicized high school athlete in the history of the state up until then,” thanks in part to his next-door neighbor, beloved Denver7 sportscaster Starr Yelland. “He used to give me as much airtime as some of the Denver Broncos. It was really embarrassing.”

He was a star basketball player, too (his dad, Vince Boryla, had been a forward for the New York Knicks), and he subsequently earned a hoops scholarship at Stanford University – “but being the dumb shit I was, I decided to play football instead. I asked them to let me try out for quarterback.” Boryla ended up becoming an All-American, a designation that included being flown to Chicago for a (fully clothed) photo shoot for Playboy magazine. Afterward, he remembers, “I went to a nightclub with some of the other All-American football players, and it was so wild and crazy I had to leave. I took a cab back to my hotel room and spent the rest of the evening studying the Book of Isaiah – and that’s pretty much how I made it through pro football. I did Bible studies by myself while my teammates were out partying.”

On the field, Boryla got only a limited number of opportunities to show his stuff. He made ten starts for the Eagles in 1976 and tossed two touchdown passes in the Pro Bowl. Then he jumped to Tampa Bay, only to suffer a season-ending knee injury in 1977. He played only one game for the Bucs in 1978 before choosing to walk away. “I left a huge amount of money on the table,” he allows, “but the Lord told me to quit, and I didn’t do another interview for the next 35 years – and I didn’t go to a Philadelphia Eagles game, a Stanford game or a Regis game in all that time.”

Instead, Boryla enrolled in the Florida-based Stetson University College of Law, and upon his graduation, he returned to Colorado and completed an advanced degree at the University of Denver before becoming a different kind of pro: “I practiced sophisticated business law for 26 years, then became the director of a home for unwed mothers in Arvada called Shannon’s Hope.”

During the latter stint, Boryla penned a one-man play called The Disappearing Quarterback, which he saw as a type of “apology letter to the wonderful people of Philadelphia to explain why I had to leave so abruptly.” He performed it forty times in Philly during 2014 and 2015, a schedule that necessitated him leaving Shannon’s Hope. Today he’s a full-time writer with several books available on Amazon, including a version of The Disappearing Quarterback.

Here’s a trailer for the play:

Boryla’s activism related to CTE stems from his observations of several former athletes he knew, including the late lineman Mike Webster, “who is featured in the movie Concussion, with Will Smith. He probably suffered 5,000 sub-concussive blows to his head, and he died very young. He had been living in his car and was shocking himself with a Taser gun in the head in order to fall asleep at night – and I found out he was having hallucinations that the Pittsburgh Steelers, the team he played on for eighteen years, were trying to kill him. And then there was my friend Jesse Freitas, who was a quarterback at Stanford, too; after I beat him out, he transferred to San Diego State. He also died homeless in the back seat of his car, and I’d heard these stories about him for twenty years – how he’d just lost it, how he was paranoid and thought everyone was trying to get him.”

He also references a pair of players who have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in the past year; he declines to name them in order to protect their privacy, but notes that “they’re very famous.”

His own prognosis is more positive: “I had a six-hour neuro-psychological examination about a year ago, and at the end of it, the doctor said, ‘Mike, you’re doing incredibly well.'” He admits to suffering occasional memory lapses that he navigates with the help of his wife, with whom he raised four sons – and while he had to have both knees replaced in 2018, he knows how fortunate he is to still be mentally capable.

“The average NFL career is about three and a half years, and there are studies that show the average life span for NFL players of my generation is 55 years – and every year of NFL football takes more off your life span,” he contends. “When we former players get together to talk about this, we always say the same thing: ‘Once you get to sixty, you’ll get to eighty. But the main thing is getting to sixty.'”

In recent years, as CTE fears have risen, the NFL has addressed the issue by making changes in the game related to targeting and blindside blocks, among other things, and sought to incorporate helmet designs intended to make the sport safer. But Boryla thinks that’s just window dressing.

“Here’s the deal,” he says. “Study how God designed the two and a half pounds of gray matter inside this heavy, thick skull surrounded by a quarter-inch of fluid. Then read the Second Law of Thermodynamics and look at the fact that nose guards are now 6’4″ and 350 pounds and run forties in 4.9 seconds. Then you can understand why NFL football can’t be played safely today. When I was a second-year quarterback at Philadelphia, we played the Minnesota Vikings in a game, and I got hit by the most valuable defensive player in the league – Alan Page, who became a Supreme Court justice in Minnesota. I thought he was huge at the time, but he was 6’4″ and 245 pounds. Now there are wide receivers who are that big.”

These factors make the idea of sitting down in front of the Super Bowl repulsive to Boryla – and that extends to the local squads. “I haven’t watched a Denver Broncos game since Bubby Brister was the quarterback,” he says. “I can’t watch it. It makes me sick. I can’t even listen to the announcers. They’re always giggly and laughing, like, ‘This is really a lot of fun.’ But what’s happening to the players isn’t fun. I won’t go to an NFL football game again.”