Unsplash/Erik Mclean

Audio By Carbonatix

Rules designed to give more transparency to rideshare drivers in Colorado are meant to kick in at the beginning of February, but Uber has filed a lawsuit in United States District Court seeking to declare them unconstitutional.

Under two new state laws – Senate Bill 24-075 and House Bill 24-1129 – gig driving companies like Uber, Lyft and DoorDash must disclose to drivers and passengers, on a single screen, the total amount a rider paid before tip, the amount that went to the driver, and the amount of the tip after a driver completes a given trip. The laws also require that when a driver is offered a trip, rideshare apps must disclose the total distance and time a trip is expected to cover.

On January 11, Uber filed a lawsuit against Scott Moss, director of the Colorado Division of Labor and Employment, and Jared Polis, governor of Colorado, charging that those laws, passed last May by the Colorado Legislature, are illegal and should be overturned. (Colorado’s state legislature cannot be sued.)

Uber’s lawsuit claims that the regulations unconstitutionally compel Uber to speak in a way that contradicts the company’s right to freedom of expression.

“Even under the most generous reading, they do not further any legitimate state interest,” the lawsuit says of the two new laws. “Where novel regulation infringes upon the First Amendment’s rights of free speech and the government cannot meet its burden under the law to justify such infringement, as is the case here, then the law must give way to Uber’s constitutional rights.”

Uber is asking a District Court judge to temporarily prevent the laws from going into effect and to declare both of the state laws federally unconstitutional.

Both laws were passed after years of advocacy from gig drivers. Led by Colorado Independent Drivers United, a union of rideshare workers vying for better conditions in Colorado, gig drivers successfully pushed for transparency on driver pay, trip distance and driver deactivations, all of which are part of the new laws. Uber’s lawsuit does not mention the driver deactivation portion, but focuses on upcoming regulations requiring trip distance and driver pay disclosures to customers and riders.

The two laws are very similar, but they are split between transportation network companies (TNCs), which move people, and delivery network companies (DNCs), which move items or food.

“This lawsuit is a blatant attempt by Uber to dodge accountability and continue exploiting both its drivers and its customers,” Anthony Scorzo, president of Communications Workers of America Local 7777, the union overseeing CIDU, says in a statement. “Colorado passed these laws after months of negotiation and compromise, and Uber’s last-minute legal maneuvering is a slap in the face to the democratic process.”

Drivers say that rideshare companies have taken a higher percentage of the fares paid by riders over the years. When the cross-institutional Workers’ Algorithm Observatory examined data from over 13,000 gig drivers in Colorado, the academic organization found that only about 14 percent of what customers pay goes to drivers. The Observatory also discovered that base pay for Colorado drivers decreased from about $1.50 per mile in 2019 to around 50 cents per mile by 2024.

Uber says the company is trying to increase transparency on earnings, service fees and other operational costs, but argues that “hamfisted regulations” on speech are not conducive to that goal.

“We warned the legislature that the bill would have unintended consequences and have filed this lawsuit as a last resort,” Uber says in a statement through spokesperson Stefanie Sass. “Not only would this law lead to more unsafe and distracted driving, it would increase confusion, reinforcing inaccurate perceptions about how much of the fare Uber actually takes.”

Colorado Pay Disclosures Shame Uber, Lawsuit Alleges

The stated goal of Colorado’s new rideshare legislation is to provide information to drivers and riders about where fares really go, but Uber alleges that the intended effect of the law is to create the perception that Uber greedily takes every dollar that doesn’t go directly to the driver in profit. According to Uber, much of that money goes toward paying taxes, local fees and insurance costs necessary for the app to operate.

The lawsuit calls the legislation “overzealous,” arguing that “draconian” penalties for non-compliance with the legislation go too far. Under both laws, fines of $1,000 on a per-customer and per-driver basis are allowed, while the TNC act also authorizes additional $100 penalties for violating other aspects of the law.

Uber takes particular issue with sections of the law requiring rideshare companies to prominently display the payment information in a font 1.5 sizes larger than any other font on the screen. The company also argues that the legislation’s selected metrics of rider cost and driver pay alone don’t accurately portray how much Uber makes off of each ride. But to display what Uber says is a more accurate cost breakdown would require so much information on the screen that it would be unsafe, the company says.

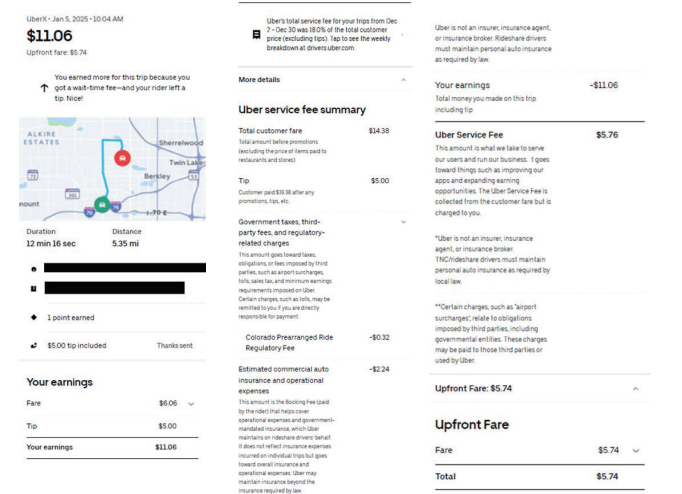

An example of a full service fee breakdown from Uber.

Uber lawsuit

“The Service Fee that drivers pay Uber is not the only amount that makes up the difference between what a rider pays and a driver’s earnings,” the lawsuit says, citing things like toll roads, mandatory driver insurance and “other government-mandated taxes.”

To note every item in the service fee after every ride on a single screen would lead to tiny text and way too much information for drivers who may already be hitting the road to their next destination, the lawsuit contends. According to Uber, having to create this disclosure page would also delay deployment of the current post-ride page that asks drivers to rate riders and vice versa, which is important for safety.

The disclosure page would take about fourteen seconds to load, Uber adds, compared to the rating page, which is instantaneous. According to the lawsuit, such a lag could contribute to safety incidents on the road.

Additionally, Uber argues that the weekly summary sent to each driver showing their earnings, various fees and taxes that make up the service fee and the total amount customers pay in one week is a more accurate picture of rider pay versus driver earnings than what would be seen on a ride-by-ride basis.

“The government designed these disclosures to shame Uber as to driver earnings by making them appear smaller than what they are relative to Uber’s revenues,” the lawsuit says. On the rider side, Uber argues that passengers already get receipts that explain where their money went, so the disclosure requirements are not necessary.

Uber Claims Unfair Burdens, but Drivers Aren’t Buying It

Uber’s lawsuit argues that drivers could be tipped less because of the laws, as well. Rather than a tip screen being the first thing people see after a ride, the disclosure page would be first and could take “about a dozen seconds” to pop up.

“Riders may not wait that long and may forget to tip or choose not to tip at all,” the lawsuit suggests. “Further, Uber would have to disable multiple tipping options, including the option to tip while on trip, because it would be prohibited from providing an option to tip until the mandated information is available, and it is not until the trip is complete.”

To meet the requirements of the law, rideshare companies would also have to tell drivers the aggregated mileage and time of each task when the task is first presented to a driver. Currently, Uber splits that information into legs showing time until pickup and time once the passenger (or food item) is in the vehicle. Uber says the current screen gives drivers more information than an aggregate measure, but Colorado’s new laws won’t allow the extra information to be included without creating a cluttered – and thereby unsafe – screen.

Finally, the lawsuit takes issue with the new requirement that Uber estimate how much drivers may need to deduct from their income in taxes. Uber is not a tax advisor and does not want to run into trouble if the estimates are incorrect, as circumstances vary on a person-to-person basis.

Uber also argues that Colorado has placed an unfair burden on the company to create different mandatory screen flows that are only required in a single state, increasing the risk of glitches and the cost of ongoing maintenance.

But driver advocates say the rules aren’t overly burdensome, and are designed with a specific purpose in mind.

“These transparency laws are about fairness – giving drivers the information they need to understand their earnings and letting riders see where their money goes,” Scorzo continues. “Uber’s decision to fight these basic protections in court shows that they care more about protecting their profits than supporting the workers who power their platform.”

Co-op Colorado, a rideshare app owned by drivers and designed to compete with Uber and Lyft, went live last fall and complies with the requirements of the new laws.

On behalf of director Moss, the Division of Labor and Employment says the office does not comment on active litigation. Governor Polis’s office declined comment.