Unsplash/Erik Mclean

Audio By Carbonatix

At the beginning of February, both Uber riders and drivers in Colorado received messages informing them they needed to update the app.

The required app updates are due to two new laws passed by the state legislature last year requiring gig driving companies like Uber, Lyft and DoorDash to disclose more payment information to drivers and riders.

Now, gig driving companies must share, on a single screen, the total amount a rider paid before tip, the amount that went to the driver, and the amount of the tip after a driver completes a given trip. The new laws also require that the apps disclose to drivers the total distance and time a trip is expected to cover before they accept the task. The laws are very similar but split between transportation network companies (TNCs), which move people, and delivery network companies (DNCs), which deliver goods or food.

Uber tried to prevent the laws from taking effect with a lawsuit in January and requested a preliminary injunction in the meantime. But a District Court judge denied that request, keeping the laws and app updates active for now.

The company argues that the two laws unconstitutionally compel Uber to speak in a way that contradicts the constitutional right to freedom of expression. Uber also contends that the new laws require too much informational text that could cause safety issues and unfairly give the impression that Uber greedily takes every dollar that doesn’t go to drivers in profit. The reality, according to the lawsuit, is that some of that money goes to taxes and insurance costs the company is required to pay.

At the end of January, drivers received a message from Uber with the subject line, “Negative impacts of new Colorado law.”

“Riders will no longer be able to tip during trips, which will mean millions in lost earnings for Colorado earners every year,” the message read. It also warned of a “text-heavy rating screen that increases the risk of distracted driving.”

Plus, Uber said drivers would lose access to four Uber Pro rewards: area preferences, priority support, premium support and extra destination filters. Area preference allows drivers to select one of five districts within Denver to work inside for two hours per day if drivers maintain a high ride acceptance. According to one active driver, Uber’s suggestion that the new laws necessitate these eliminations is untrue.

“There’s nothing in the law that says you can’t have area preference,” says Elliott Awatt, an Uber driver who is part of Colorado Independent Drivers United, a union that formed to push for better conditions for rideshare drivers and advocated for the new laws. “I’m on a team of people that reviewed that law and we’ve not found anything that says that the law requires them to do this. This is strictly retaliation.”

Awatt believes the change is designed to turn drivers away from CIDU by making it seem like their advocacy for the legislation actually hurt drivers. The same goes for the other rewards drivers can no longer access, he says. In all cases, nothing in the law seems to point to those rewards not being allowed anymore.

Priority and premium support enable Uber drivers with a certain rating to call a support number and speak to a real person instead of going through the company chatbot when problems arise. Even something as simple as someone leaving their wallet behind is more complicated with a chatbot involved, Awatt says.

“I honestly have safety concerns about that,” he adds, noting drivers now have to find a place to pull over and park to use the support bot, which cuts into earnings. “I’ve had situations where it’s taken an hour or two for someone at Uber to respond, versus I can make a phone call and we take care of whatever that small issue is really quickly.”

Finally, the extra destination filters allowed drivers to pick two destinations per day they needed to get to so Uber could route them in that direction. That was helpful for drivers who took riders between cities, such as a trip from downtown Denver to a suburb like Parker where demand isn’t as high. Now, Colorado drivers don’t have the option to get back to their home area while working except through luck of the draw.

“We made these changes to comply with the law,” Uber says through a spokesperson, citing the legal requirement to disclose total amounts given to drivers before riders can tip as an example. “Because the total fare is not final before the trip is over, we could not allow riders to tip until after the trip is over. …During the legislative process, we warned that this law would have unintended consequences and this is one of them.”

Uber said impacts to rewards “occurred as a consequence of compliance with the law” but did not reply to multiple questions about which parts of the law required those changes.

Both Co-op Colorado, a rideshare app owned by drivers that went live last fall, and Lyft comply with the new rules. According to Awatt, Lyft has always shown the exact pickup and destination addresses to drivers before the law requiring those measures went into effect.

“If Lyft can do it, I believe Uber can too,” he says.

Testing Out Uber After Colorado’s Required Changes

Although Lyft’s compliance updates add almost zero extra difficulty to the ride and tipping process, Westword found the Uber app buggy during our test run since the changes took place.

The ride request process was the same as always, and a pickup outside the Westword office and subsequent ride to RiNo went smoothly with a polite, safe driver.

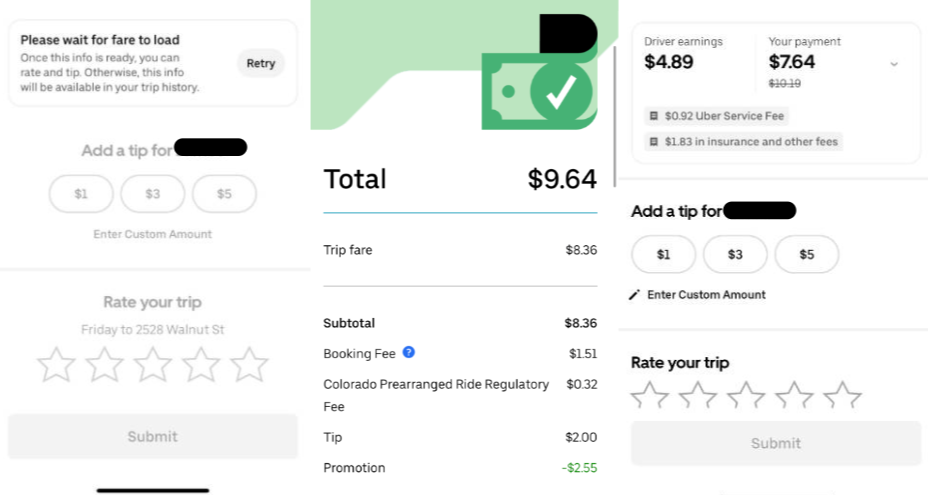

On the rider end, we couldn’t see how much the driver would make before or during the ride. True to Uber’s word, we weren’t able to find an option to tip during the ride despite clicking around into every window on the app we could find.

After the ride was over, a screen popped up instructing us to wait for our fare to load.

“Once this info is ready, you can rate and tip,” the screen said. “Otherwise, this info will be available in your trip history.”

In the lawsuit, Uber had warned it could take “about a dozen seconds” to load the information, resulting in some riders giving up before they could tip. It was much worse during our test. After waiting five minutes, the screen still hadn’t repopulated with fare information, and hitting the “retry” button seemed to do nothing.

At that point, we gave up on waiting out the screen and went into our trip history. There, we could tip immediately. We also had an emailed trip summary that arrived one minute after our ride ended with a tip option.

Any rider who wants to tip will definitely be able to, but waiting was frustrating and seemed unnecessary.

The three tip and fare information screens we saw after Uber’s new updates.

Uber app screenshots

Another item Uber had emphasized in the lawsuit was that screens fitting the requirements would be too wordy. This was not our experience. The screens felt clean and easy to understand.

On the driver side, Awatt says he’s found the same to be true. He also said the rider rating screen, which Uber anticipated could take fourteen seconds to load, has been popping up quickly after rides without a noticeable delay.

Uber’s lawsuit also warned tips could decrease because of the laws, but Awatt says he has found either his usual tip amount or even higher tips in some cases.

“If anything, when passengers are presented with the proper information, they actually tip better,” he says. “It’s my opinion that Uber doesn’t want the general public to see what they’re up to, because then you guys are going to get on our side and demand a change.”

Solidarity between drivers and riders is the top item Awatt hopes emerges from the app changes, even if they do provide a learning curve at first.

“I want riders to pay attention to what their drivers are actually going through,” he says. “At the end of the day, you’re a member of this community, and I’m a member of this community. You need a ride, and I have a vehicle. This technology company that’s based in Silicon Valley is literally taking 50 percent or more of every trip, and that’s hard-earned Colorado money that has to leave the state of Colorado.”