Brantley Hargrove on Chasing Storms and Tim Samaras

The author will be at the Tattered Cover April 23.

April 23, 2018

Brantley Hargrove

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]

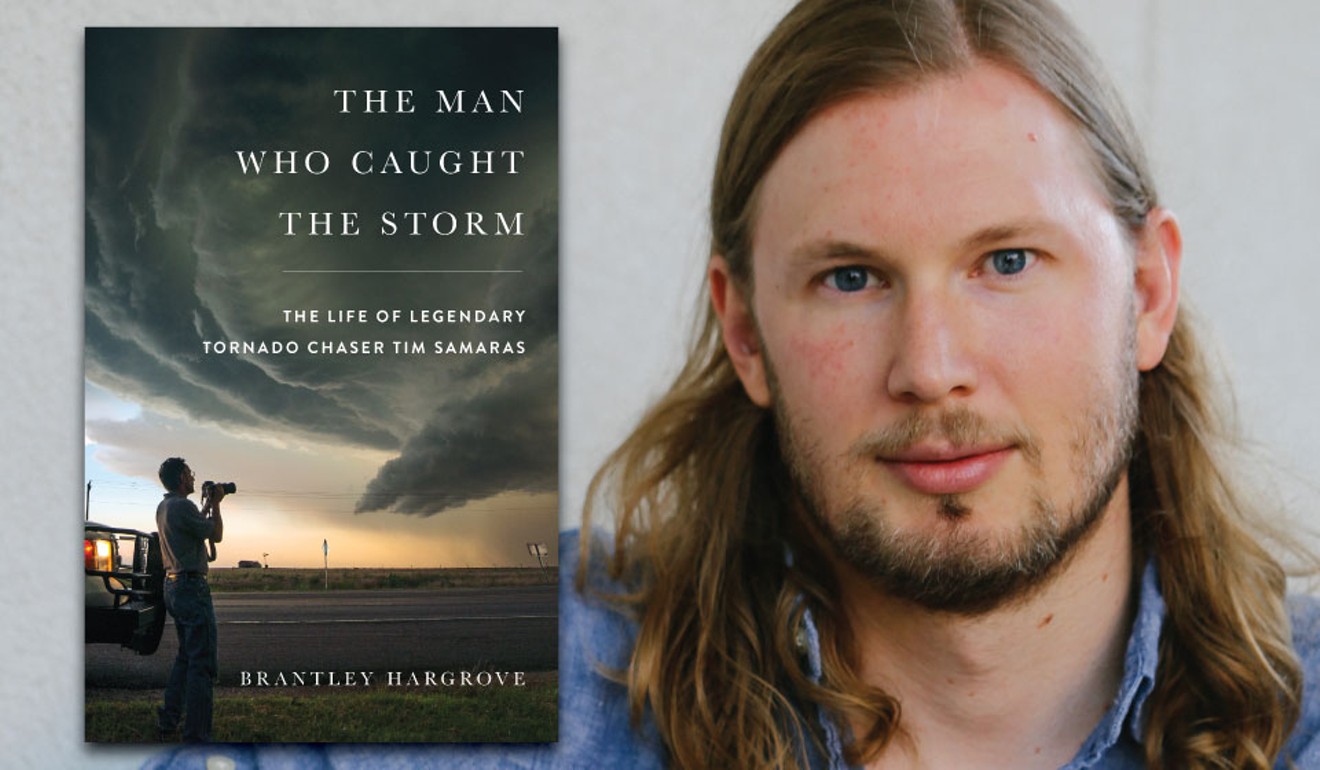

For decades, Tim Samaras chased storms, studying them and vastly expanding the science of what created such severe weather phenomena. Author Brantley Hargrove never met the Denver man, but as he researched his life and death — first for a cover story about Samaras for our partner paper, the Dallas Observer, then for the book The Man Who Caught the Storm: The Life of Legendary Tornado Chaser Tim Samaras — he came to know Samaras. In advance of Hargrove's appearance on Monday, April 23, at the Tattered Cover Colfax, he shared some of his thoughts on Samaras, storms, and writing books.

Westword: What drove you to write this book?

Brantley Hargrove: I grew up with the Twister generation. The year after the movie’s release, when I was fifteen, Jarrell, Texas, found itself in the path of a monster. Nearly thirty people were killed. To this day, it’s considered the most destructive tornado ever documented, pound for pound. I’d stocked shelves in that town’s general store the year before. I think I was primed for an unhealthy fascination. I’d seen firsthand what tornadoes can do. Here was a man with the guts to face them down and to learn from them. How could I not write about this person?

What made Tim Samaras become so interested in tornadoes and storm chasing?

It started with The Wizard of Oz. He was transfixed by the tornado on screen, which even by today’s standards still looks pretty lifelike. Growing up near Denver, on the doorstep of Tornado Alley, twisters were simply a part of his natural world. He wanted to see them up close, but he didn’t know how. In 1985, he saw a NOVA documentary about a troop of researchers who didn’t wait for the the tornado to come them. They chased it down with sophisticated probes. It was a revelation for Tim. He’d never dared to think such a thing was even possible. He wanted to do what these scientists did. He wanted to chase.

Why do you think that tornadoes are so compelling?

How often in the natural world do you witness something bigger than any skyscraper roaring over the plains like a vision out of a bad dream? High-end tornadoes contain winds that can loft an SUV for three quarters of a mile. They can strip a house down to its concrete foundation. To see a tornado like that is to feel as though you’re in the presence of an aberration — something that shouldn’t exist but is all too real.

I understand that you have decided to take on storm chasing yourself. Knowing the risks, what has made you decide to pursue it? What does your wife think?

To understand Tim Samaras and his world, I knew I needed to walk a few miles in his shoes. I had to see for myself what drew him away from home year after year, like a siren’s song. In Pilger, Nebraska, I witnessed an historic event. We saw four EF4 tornadoes in June 2014. They were each as wide as five football fields laid end to end. Two of them were on the ground simultaneously. That day, I think I understood Samaras a little better. Even after this book was already finished, I found myself drawn back out there. In 2017, a former TWISTEX member and I were forced to hunker down against the wall of a Pizza Hut as Hurricane Harvey’s eyewall passed over us. There’s something addictive about being there as the atmospheric equivalent of a nuclear warhead is detonating. We made it out unscathed, but my wife has since decided that my storm-chasing days are over.

We’ll see about that.

In the course of your research, you have become something of a tornado expert yourself. What are some of the most surprising things that you have learned?

I know just enough to be dangerous. What fascinates me most about tornadoes is just how little we really know. So many unanswered questions remain. We’ve gotten better and better at detecting the conditions most conducive to producing the really bad days. Yet sometimes these conditions are present and nothing happens. I found that out firsthand while I was chasing. There’s some signal in the atmosphere that we can’t see yet. In fact, we may not even have the tools to see it. I think that’s remarkable. Our dominion over nature is far from complete. There are still mysteries out there.

If someone wanted to become an amateur storm chaser, what advice would you give them?

Be careful. Respect the power of the sky. Take a Skywarn storm-spotting course. Find an experienced chaser willing to show you the ropes. And above all, keep your distance, especially from rain-wrapped tornadoes.

In the last few years, climate change has worsened. Has it had an effect on storms?

The jury is still out on the effect of climate change on severe storms. There’s some research out there that suggests the frequency of the highest-end events is increasing. As the oceans warm and evaporation rates grow, it makes sense that there’ll be more available heat and moisture in the air. That’s exactly what storms feed on. But there’s also research that suggests an attendant decrease in wind shear, which is also necessary to produce spinning storms. The prevailing theory now is that tornadic storms could be fewer in number in the future. But there’s a big caveat: When they do happen, they may be much, much more violent.

Samaras’s story is so inspiring, particularly that he was able to become such an innovator in the field of tornado science despite never having gone to college. You write, “He has long been fueled by his role as an outsider.” Could you elaborate on this?

Samaras never cared for sitting still in a classroom. He was one of those guys who learned best by following his own passions. He learned by doing. He never took the traditional route, and it had always worked for him. The guy went straight from manager at a mom-and-pop radio-repair shop to instrumentation engineer with a Pentagon security clearance and access to the military’s most dangerous weapons. Samaras came from a culture where you’re measured by what you can do, not by your academic pedigree. Suffice it to say the world of atmospheric science is a bit different. But tell him he isn’t qualified to do something and you’ve just guaranteed that he’s going to give it everything he’s got. Paired with his innate curiosity, I think ambition and a drive to prove the doubters wrong spurred him onto his historic measurement in Manchester, South Dakota.

Samaras was the first person to be able to measure the atmospheric conditions inside the core of a violent tornado using instruments of his own design, which you describe as “meteorology’s equivalent of the moon landing.” What made this feat so groundbreaking?

Prior to his measurement of the F4 tornado in Manchester, we had no data at ground level, from the core. Scientists who studied theoretical tornado structure had to guess at what was going on down there. Damage surveyors had to estimate wind speeds based on degrees of destruction to houses and buildings of irregular structural integrity. Radar — an exceptionally valuable tool — couldn’t direct its beam that low. The low-level tornado environment was a blank space in the equation. Samaras filled it in. It wasn’t an answer to all the questions; it didn’t solve the riddle. But it was a damn good start. He proved this was possible.

You describe Samaras as having been not a thrill-seeker, but very cautious, and how he was successful as a storm chaser because he “succeeded by toeing the line between danger and safety." What do you think went wrong for Samaras with his last storm?

Make no mistake: What Tim did — attempting to deploy probes inside tornadoes — was orders of magnitude more dangerous than my own chasing experiences. To get a probe into the core, Samaras had to enter the tornado’s path, a place in which the average chaser should never find himself or herself. During his last chase, everything that could go wrong, did. I believe Samaras, his son, Paul, and meteorologist Carl Young were attempting to head the tornado off in order to deploy. At the end, it did several things that caught them off guard. The tornado accelerated to highway speeds, grew drastically in size, and hooked sharply to the north, toward their vehicle. For much of their chase, the vortex had been wrapped in rain. I don’t think they even saw it coming.

Is there anything you want readers to take away from your book?

I hope they walk away from this book with a renewed sense of awe toward the wild and mysterious world around them. I hope it inspires some of them to contribute to what we know about that world, like Samaras did.

What books did you read in preparation for writing this book? Whom would you consider your biggest literary influences?

Mystery of Severe Storms, by Theodore Fujita, Tornado Alley, by Howard Bluestein, and too many scientific papers to list here. I think The Man Who Caught the Storm can be traced directly back to Sebastian Junger’s The Perfect Storm. When I was a freshman in high school, it was the first nonfiction book I’d ever read that had me hanging on every word, every page. I read it again — for probably the fourth time — as I was figuring out how to write my own book.

What are you working on next?

That remains to be seen, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it has something to do with natural phenomena. The world is an endlessly interesting place.

Brantley Hargrove will discuss and sign The Man Who Caught the Storm: The Life of Legendary Tornado Chaser Tim Samaras at the Tattered Cover at 2526 East Colfax Avenue at 7 p.m. Monday, April 23. Admission is free; the Simon & Schuster book is $26. Find out more at tatteredcover.com, and thanks to Simon & Schuster and Hargrove for this Q&A.

BEFORE YOU GO...

Can you help us continue to share our stories? Since the beginning, Westword has been defined as the free, independent voice of Denver — and we'd like to keep it that way. Our members allow us to continue offering readers access to our incisive coverage of local news, food, and culture with no paywalls.

Can you help us continue to share our stories? Since the beginning, Westword has been defined as the free, independent voice of Denver — and we'd like to keep it that way. Our members allow us to continue offering readers access to our incisive coverage of local news, food, and culture with no paywalls.

Newsletter Sign Up

Enter your name, zip code, and email

I agree to the Terms of Service and

Privacy Policy

Sign up for our newsletters

Get the latest

Arts & Culture news,

free stuff and more!

Trending

Use of this website constitutes acceptance of our

terms of use,

our cookies policy, and our

privacy policy

Westword may earn a portion of sales from products & services purchased through links on our site from our

affiliate partners.

©2024

Denver Westword, LLC. All rights reserved.

Do Not Sell or Share My Information

Do Not Sell or Share My Information