Verizon, the $233 billion telecommunications company, created the Denver Tech Future website, which it calls a “community-focused initiative." According to Denver Tech Future, 5G will lay the groundwork for the Internet of Things, in which the basic items of our daily existence — refrigerators, lamps, cars, etc. — will send data to each other automatically. It will help make augmented reality, in which a computer-generated image is superimposed on our view of the real world, an essential feature of navigation. Once we’re able to share massive amounts of information at lightning speeds, Denver Tech Future’s website says, it will “change society in unpredictable ways” at an “exponential pace.”

But in the view of many Denver residents, 5G is nothing but an infrastructural nightmare — an eyesore and a burden on their property value — and a source of endless worry about potentially adverse health effects.

Katy Kaye and her family tried to stop the construction of a 5G small cell pole in her yard by planting a tree where it was supposed to go.

Courtesy of Katy Kaye

But there’s a catch. Actually, there are a lot of catches, including increasing the risk of cyberattacks and potential for surveillance, and exacerbating the divide in Internet access between rural and urban areas. But 5G operates on a much higher electromagnetic frequency spectrum than previous mobile networks. The wavelengths it sends out have a higher capacity but a shorter range, which means that large towers that serve dozens of square miles won’t cut it. To make the network effective, “small cells” will have to be placed every few hundred feet. And even then, it will be difficult for waves to penetrate through walls, trees, cars or glass, impeding indoor coverage. Not least, to access the network in the first place, you’ll need to buy a 5G-enabled smartphone and add 5G access to your plan.

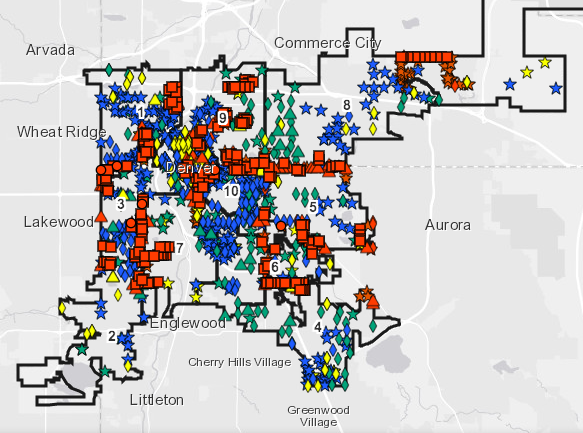

According to Heather Burke, a spokeswoman for Denver Public Works, 122 new poles, each about thirty feet tall, have been constructed specifically to house this new small-cell technology. They're labeled "CityPoles" by the Boulder-based company that builds the physical infrastructure. Many are owned by Verizon, but some are also owned by AT&T, Crown Castle or Zayo Group (the latter two are companies that build small cells and lease them to carriers). This map shows where proposed and existing poles are.

Many people complain that the CityPoles housing Verizon's small-cell technology are bulky and ugly.

Denver Public Works

Additional small cells have been installed in existing street lights and utility poles, all of which are owned by Xcel Energy. After Denver Public Works requested that companies integrate small cells into existing towers instead of building their own, Xcel agreed to sell space on its monopoly of vertical infrastructure (for how much is unclear — Xcel and companies signed non-disclosure agreements). Verizon has also asked to put small cells on traffic lights (which Xcel also owns), but the city is still evaluating whether to allow that.

The purpose of the small cells is twofold. Some of the poles will house technology that aims to “densify” and improve the existing 4G LTE network, which is being strained as demand for wireless data increases. Others will lay the groundwork for the potentially much more powerful next-generation 5G service. Because 5G small cells cover a much shorter distance, there will eventually have to be more of them — hence the demand for freestanding poles. Because each pole only houses technology for one mobile carrier, Denver could see hundreds or thousands more as companies expand their 5G networks in the coming years. As of now, there’s no way to know whether a pole houses a 5G cell, a 4G cell, or both.

According to Verizon spokeswoman Heidi Flato, Denver's 5G network will first be concentrated in Highland, LoDo, Capitol Hill, Denver Tech Center, and around popular landmarks. Verizon turned on its network in Denver July 1, Flato says.

All four major mobile carriers are working on implementing 5G networks, but as Verizon puts it, “There is 5G, and then there is Verizon 5G Ultra Wideband.” AT&T has yet to launch 5G for consumers, T-Mobile’s network is in a limited startup phase, and Sprint (which is set to merge with T-Mobile pending a Federal Communications Commission vote) has a network, but testers found it was on average more than three times slower than Verizon’s. Verizon is right: It’s the leader in this technology so far, at least in Denver. But that’s also making it the face of public discontent.

The Federal Communications Commission has done its best to make it easy for companies to implement small-cell infrastructure, putting caps on fees that municipalities can charge and requiring permits to be approved within ninety days. In 2017, Colorado passed a law that confirmed that telecommunications companies have the right to construct small cells in what’s called the “public right of way.”

In Denver, that’s the several-foot span that stretches inward from the street curb, and it's owned or controlled by the city, even if it’s in someone’s yard. Companies must go through a permitting process with the Department of Public Works, which, according to Burke, regulates locations to ensure that poles are "less intrusive to the public and adjacent property owner." But, she wrote in an email to Westword, "Denver can’t limit how many there are or restrict access" because the law establishes that cities cannot flatly deny permits or favor one company over another; they can only regulate based on the protection of public health, safety and welfare.

Some residents are arguing the city should do just that, though. They take issue with what they see as the towers’ clunky, industrial appearance or fear that towers will reduce the property value of their house or turn customers away from their business. They point to San Francisco, where a court has allowed the city to limit 5G infrastructure for aesthetic reasons. Others fear that they will get "microwaved"; that is, that the higher-frequency wavelengths will damage DNA, cells and organ systems, or even cause cancer. Brussels banned 5G because of health concerns in April, as have several small municipalities in California. Boulder held an educational panel on the health effects last month after residents and city councilwoman Cindy Carlisle raised claims against 5G.

Much of the frenzy surrounding the impacts of 5G radiation can be traced to a controversial 2000 study that raised alarms about wireless networks in schools after a researcher found that microwave absorption in brain tissue increases exponentially at frequencies above 1000 megahertz. Scientists now say that study ignored the barrier effect of human skin. 5G networks, being complex new technology, will use many parts of the radio spectrum, which ranges from 3 kilohertz to 300 gigahertz; Verizon's Ultra Wideband uses super-short "microwaves" ranging from 28 to 39 gigahertz. The exposure levels for 5G networks fall well within the federal standard for safety for signals operating at that frequency. But many insist that those exposure levels haven't been conclusively studied; a group of 180 scientists and doctors have petitioned the European Union to halt the 5G rollout.

One Denver family put up a valiant but ultimately unsuccessful battle against the construction of a new pole. Katy Kaye and her husband bought their house in Congress Park earlier this year. The previous owner had received a notice that Verizon was planning to build a new single-carrier small-cell pole in front of the house, but did not disclose this before the purchase, Kaye says. She only found out when a neighbor told her someone from Verizon had been measuring the site on the right-of-way.

After unsuccessful attempts to reach out to Verizon, Denver Public Works and Denver City Council to find out how to stop it, Kaye discovered that the company was not allowed to put up the pole within 15 feet of a tree. (According to Cynthia Karvaski, a spokeswoman for Denver Parks and Recreation, this is the case for all vertical structures, which could run into a tree’s root system if constructed too close. But Verizon also notes that even objects like foliage can interfere with 5G wavelengths and make the signal less effective.) So the Kayes bought a Japanese Blossom tree and planted it right next to the planned site.

When Verizon workers came the next day to start digging, they were forced to turn around. After a week or so of back-and-forth, Verizon called Kaye to tell her that “the pole was going in and there was nothing we could do to stop it,” she says. The day after that, Kaye had her kids set up a lemonade stand on the planned site. Verizon workers arrived to try to start construction again (at which point neighbors came to join the small protest). Eventually, according to Karvaski, Verizon got a permit to remove the tree, since its permit had been granted first. Finally, on August 9, in a somewhat heated moment, Verizon employees told Kaye they would start construction even if her kids were outside, so she relented and they built the tower.

Katy Kaye's daughters set up a lemonade stand to protest and block the Verizon small-cell pole going up in front of their house.

Courtesy of Katy Kaye

Others share that concern. According to Burke, the review process for small-cell permits requires companies to notify adjacent property owners and "gives other City agencies, utility companies, and registered neighborhood associations a chance to weigh-in" with online comments on specific applications. But when Verizon also recently constructed a small-cell tower in front of the apartment building where Ariana Lebovits lives in Congress Park, she says at first she and other residents had no idea what it was. She contacted her building manager, who also didn’t know anything about it. By the time she figured out what it was, there was nothing they could do. “From the beginning I think there should have been more transparency and communication,” she says.

Lebovits is also concerned about health risks, and the pole is making her re-evaluate her original intent to stay at her apartment long-term. “People are going back and forth about conspiracy-theory stuff, and it is hard to differentiate that, just because we know so little about this technology,” she says.

Mae Della Stiger owns a barber shop in a historic district of Five Points. She was notified last year that an Xcel street light in front of her shop was going to be replaced with a new LED one, but, she says, an AT&T small-cell pole went up in its place. (The city map did not confirm the location of this pole, but it does not claim to be a comprehensive record of all pole locations.) “It’s forty feet in the air and seven and a half feet in front of my doorway, and you cannot see my address from the stoop,” she says.

Stiger feels that black and brown communities are being used as “guinea pigs” for the new technology. (Verizon says that the 5G rollout will be targeted toward highly dense areas, but that may mean overlapping with communities of color.) “They should set up a meeting; they shouldn’t just have the right to come in and do as they please. I know money talks, but we still have a voice. The businesspeople paying into this district need to know what’s going on,” Stiger says.

Stiger contacted her councilwoman, Candi CdeBaca, to see if there was anything she could do. CdeBaca says that sent her office on a “wild goose chase” trying to figure out what the tower was and who in the city had power over it. “I actually had no clue that we had so little influence and power over communications towers,” CdeBaca says. “It doesn't feel like there's a lot that can be done, but obviously all of us are trying to figure out how to help our constituents, because it has become a pretty consistent concern.”

That’s what led CdeBaca, Stiger and dozens of other residents to an “open house” that Verizon hosted at the Carla Madison Recreation Center on Wednesday, August 14. “We want to be a good neighbor, so part of that is helping to educate the public and convey the benefit of 5G to the community,” Heidi Slato, a spokeswoman for Verizon, explained. And, she added, “We do [these events] when we know folks have questions and are perhaps opposed to the technology."

During the open house, confused, concerned (and perhaps opposed) residents asked Verizon employees questions about the technology, the permitting process, and plans for 5G network expansion; the event had been planned after the company realized that Congress Park residents were especially unhappy about new poles and infrastructure. But information at the meeting didn't seem to ease dissatisfaction. As one employee explained the benefits of 5G and the federal regulations that allowed companies to install technology with safe levels of radiation in the right-of-way, a woman responded, “But what if we don’t want it?”

That comment resonated with others at the meeting. As Neil Slade, who lives in Congress Park and has strong feelings of opposition to 5G, echoes, “The whole thing is a scam. People don’t want this, but it’s been forced upon them.”

“I think everybody wants faster connection and Internet,” CdeBaca says. But she’s leery about the methods companies are currently using to get us there. “I think people will really question the costs of it, whether that's health costs, the aesthetic costs... . There are costs to things that aren't always monetary.”

Update: This story has been updated. At the time Verizon applied for the small cell pole in Congress Park, the guidelines were a minimum of 15 feet separation between new freestanding poles and trees.