That's a positive for the Denver economy, at least in the short term. But down the road, the trend may be bad news for renters without such fat wallets.

"I don't know that you're seeing a whole lot of affordable rental places being built," says Scott Grossman, who's both a major player for Madison & Co. Properties and a past boardmember of the Denver Metro Association of Realtors. "Everybody wants to get in on the game when they can, and if they can make more on upper-end product, they do. You're seeing that on the purchase and rent end of things."

Rob Warnock, research associate for Apartment List and author of the February report "Rich and Renting: Understanding the Surge of High-Earning Renters," adds that "from an economics perspective, adding new supply to the top of the market reduces competition for older, existing housing stock. Of course, this does not single-handedly solve the access-to-housing problem for lower-income households, which is why many cities have affordable-housing requirements for new developments."

Denver has just such an initiative, as outlined in our post answering the most-asked questions about affordable housing. But the city's efforts are focused on assisting the neediest of those seeking housing, and staffers and officials can't help every single person in such a situation because of limited resources. Note that last year, 21,000 interest cards were submitted in regard to the Denver Housing Authority's Housing Choice voucher-program lottery, from which between 200 to 500 winners are selected on an annual basis. Moreover, around 12,000 interest cards are on the waiting list — and that's not to mention renters who make too much to qualify for the lottery but not nearly enough to afford to rent the kind of pad constructed with high-income renters in mind.

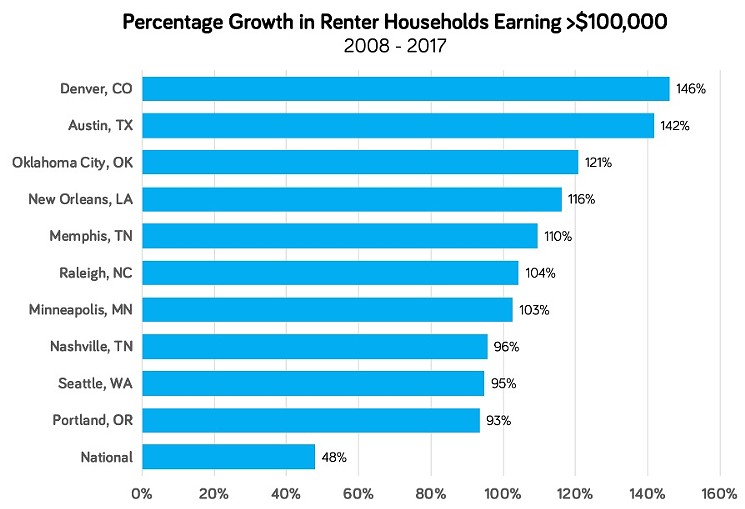

Here's a graphic showing the cities that experienced the largest percentage growth in high-income renters between 2008 and 2017, the most recent year for which statistics are available. As you can see, Denver's total is four points higher than the number-two finisher, Austin, and 53 percent above Portland, Oregon, which landed in tenth place. As for the national average, Denver exceeds it by 98 percent.

When asked about the major factors that resulted in Denver having the greatest surge in high-income renters over the past decade among the communities surveyed by Apartment List, Warnock, corresponding via email, points out, "We think both 'push' and 'pull' factors are driving Denver’s growth of high-income renters. Some of the city’s high earners are being pushed into the rental market simply because even for them, the homes they desire are too expensive to buy outright. Others are being pulled or drawn into the rental market by the abundance of rental options that cater to whatever lifestyle they want to live. We have witnessed a boom in multi-family rentals for those who prefer density and centrality, alongside a boom in single-family rentals for those who prefer more space."

In Warnock's view, "Denver checks all of the boxes when it comes to factors that attract high-income renters. It has a strong and growing economy, high-paying jobs, a relatively affordable housing stock that is receiving lots of investment, and popularity among younger professionals who are more likely to rent than own. Some of the nation’s biggest and wealthiest cities do not top the list because in 2008 they already had a large base of high earners who were renting; it’s a newer phenomenon in places like Denver. In 2008, only 9 percent of Denver’s high-earning households were renters; by 2017, that rate rose to 16 percent."

This demographic shift has had an impact on development in Denver for years. As revealed by a previous Apartment List report, Denver was ranked second in the country for multi-family housing construction per capita circa 2016, and Warnock acknowledges that "new multi-family construction is well suited for high-income renters, since these units tend to be on the more expensive side."

He also concedes that developers often focus on the high-income demographic because such units tend to be more profitable over time than those intended for low- and moderate-income renters. In his words, "As the cost of land increases, as it has been doing in cities throughout the country, it makes sense that new development will target the higher end of the market in order to remain profitable. The high cost of construction plays a similar role."

In this respect, Denver development for renting and buying share much in common. "It's very similar to the purchase market, where it can be hard to find that low end," Grossman says. "Things have simmered down a little bit from where they were, when sellers were following this incredibly steep appreciation curve and pricing things at a higher amount and still getting above asking price. But I've personally seen a lot of competitiveness in the $800,000 to $1.2 million area — and that price point has become more like the homes in the old $400,000-$600,000 range. Not that it's the same homes appreciating so much, but I think with all of the people who are coming into Colorado from places like California, these homes still seem extremely affordable to them versus where they've come from."

The Union Denver complex boasts studio apartments starting at $1,620 per month, one bedrooms from $1,790 and two bedrooms that can be had for $2,860.

On top of that, however, "the real estate market's inventory was at historical lows for such a long period of time," he continues, "and we had people frustrated trying to buy a house with all the bidding wars. You'd have to get your offer in that day, and you'd be going up against seven or ten other offers — and only one of them can win. That can grind on people and make them feel like, 'Maybe I'll stay on the sidelines for a while.'"

Now that the housing inventory is starting to creep upward again, Grossman thinks some high-income renters will begin looking at buying again. "It'll be interesting to see if they're going to stay in the rental market or get back in the game. And if people are looking at home ownership long-term, now's the time to get locked in before the rates go up."

If lots of folks make this decision, could Denver eventually wind up in a situation where there are plenty of expensive rental apartments sitting empty and a shortage of places for renters of more modest means? Warnock doesn't dismiss this prospect.

"No doubt this is a tricky situation that America’s most expensive cities may be approaching," he concedes. "Over time, units representing the higher end today will age and become more affordable. In the meantime, developers may spend more energy enticing residents to their units, either by lowering rents or offering other perks. Cities may also need to find ways of reducing the cost of construction so that low- and moderate-income housing becomes profitable for developers."