"They could say, 'We don't like you because you wear green shoes,' and that would be good enough," says Sullivan, who's currently exploring ways to alter Colorado's recall approach. "That's all they have to do right now."

He speaks from personal experience. The first-time legislator, who became an outspoken advocate for progressive gun policies after his son, Alex Sullivan, was killed during the Aurora theater shooting on July 20, 2012, took office in January. But his advocacy for measures such as red-flag legislation, which created a mechanism for taking firearms from individuals deemed a danger to themselves and others, infuriated gun-rights advocates, who targeted him under the Recall Colorado banner.

On June 11, recall leader Kristi Burton Brown, who also serves as vice chairwoman of the Colorado Republican Party, announced that the group was dropping its bid to bounce Sullivan from office after it became clear that his critics would have a difficult time collecting the required number of signatures to put the matter on the ballot. But while the endeavor was officially a failure, it succeeded in sucking up plenty of Sullivan's time, energy and resources, which he believes was one of the organizers' goals in the first place.

All that's required of outfits wishing to oust eligible officials (judges and members of the state's congressional delegation are the only listed exemptions) is to create "a general statement, of 200 words or less, stating the grounds on which the recall is sought. Proponents draft the statement, which cannot include any profane or false statements."

Sullivan was presented with this "list of charges," as he refers to it, on May 13. And if some political observers were shocked that he wound up in the crosshairs because of his personal tragedy, he wasn't.

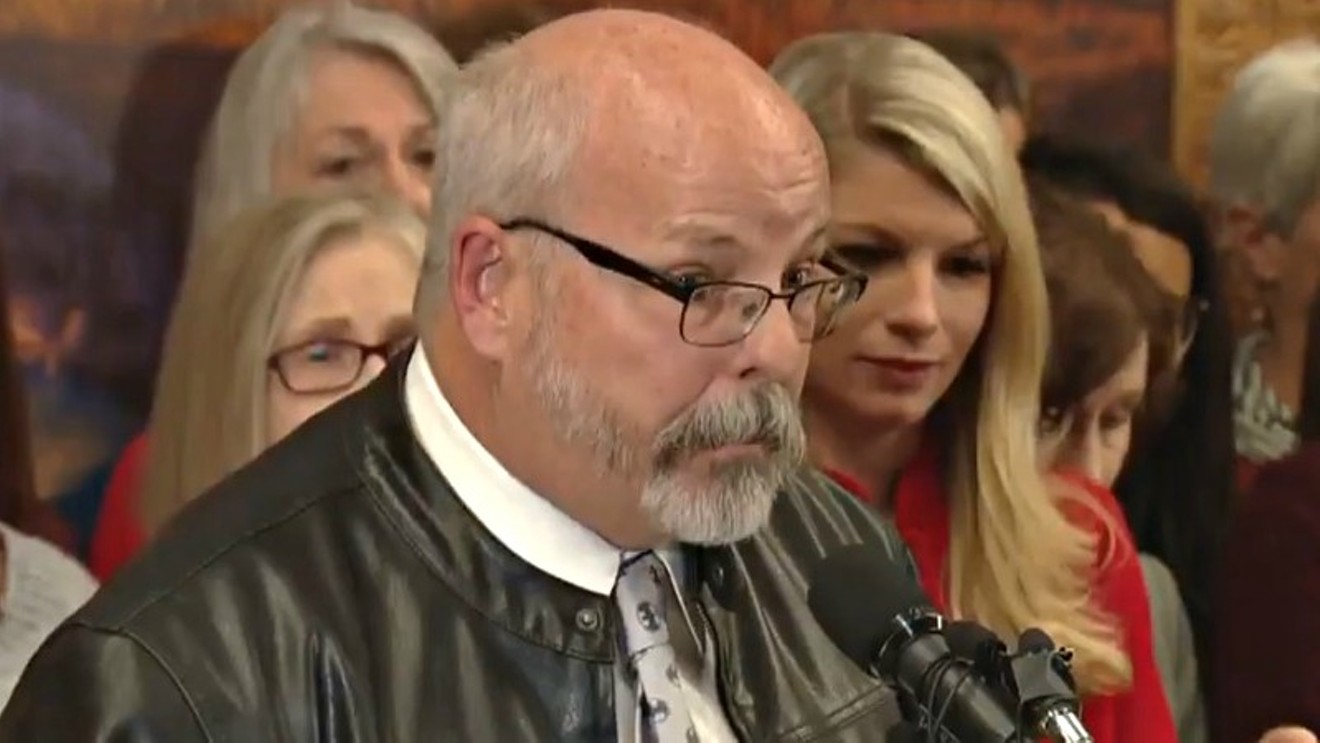

Graphics keyed to the effort to recall Tom Sullivan.

9News via YouTube

Recall Colorado had sixty days to collect 10,035 valid voter signatures in order for a recall to be approved for the ballot; the number represents 25 percent of all votes cast in House District 37, which Sullivan represents, during the previous election. As a result, he recalls, "I told my aide, 'Hey, I'm going to be in my garage getting my walking shoes and packets together to start canvassing. I'm not going to be at the office, because it's pointless to talk about other legislation and talk to lobbyists about bills, because I don't know if I'm going to be there. I'm going to get out there and defend the seat we have now.'"

During this period, Sullivan continued to hold regular town halls with voters and had an assistant answering and following up on phone calls and emails from folks in the district. But he missed out on other opportunities. For instance, he says, "There were interim committees that were starting to be announced, and I got notification from our leadership down at the Capitol that they weren't going to select me for any of them because of the recall. I got canceled out of a committee on school safety — which I had a direct link to and a lot of understanding about and would have like to have some input on — because I was fighting a recall."

In the meantime, Sullivan had to raise money to counter the forces marshaled against him; Rocky Mountain Gun Owners is said to have invested at least $30,000 in paid signature-gatherers. Groups such as Everytown for Gun Safety were among the supporters who stepped up. But each moment he spent dealing with such matters was one he would have preferred using to work on behalf of his constituents.

After the recall venture flopped, Sullivan was finally able to start looking ahead to the 2020 legislative session — and one of his first areas of analysis involved "Colorado's recall process and how it compares to other states and what kind of changes can be made. It's something no one's had the courage to do: They don't want to, because they might get people who might want to recall them angry. It will definitely draw some focus toward you, but I'm already in their focus. So what are you going to do? Recall me? Well, you already did that. So I'm very interested in seeing if there's anything I can do."

Alex Sullivan, Tom Sullivan's son, was killed during the Aurora theater shooting.

Family photo via AuroraRise.org

Colorado is among the other twelve states "that [don't] require any reason as to why you would be recalling somebody," Sullivan goes on. "Then it all breaks down to the length of time for the recall, the number of signatures and those types of things. And there's also the difference between the constitutional part of it and the statutory part of it." To establish specific rationale for a recall might require "a constitutional-type change that would require a two-thirds vote — or it might be something that would have to be put on the ballot as opposed to something where we could get a bill written up and get both houses to pass and the governor to sign."

Other options include softening the regulations. "Maybe we could make it so you can't recall somebody during the 120 days of the legislative session — and maybe getting signatures from 25 percent of the people who voted isn't enough," Sullivan allows. "Maybe it should be 25 percent of all registered voters in that district. And one state [Illinois] requires that on top of getting a percentage of signatures, you have to get a certain number of people sitting in the House and the Senate to agree to it." (To prevent partisanship, the Illinois law states that "no more than half of the signatures of members of each chamber" can come "from the same established political party.") As Sullivan sees it, "That would really show you were a horrible person if the people you're working with every day say, 'He's a bad guy. You should get rid of him.'"

While there's no such standard in Colorado, Polis is still unlikely to face a recall vote. After all, Dismiss Polis must collect more than 630,000 verified signatures by September 6, and the odds of that happening are minuscule. But the prospect of actual removal is only a small part of the problem, Sullivan feels.

"I'm not talking about doing away with recalls, but there should be changes," he says. "You shouldn't be able to threaten people like this."

Click to read Colorado's recall election rules.