eBay

Audio By Carbonatix

As restaurants reopen at full capacity and scramble for employees, we’re sharing the stories of people who got their first jobs at eateries around the area. And their last: Ivan Suvanjieff sent this memory of his time with Cliff Young, who passed away at the end of May.

Restaurateur Cliff Young only wanted the best for his customers.

After I got out of rehab, I worked at the Red Lobster that used to be on Union Street in Lakewood. A friend said I should apply at Cliff Young’s. I knew nothing about Cliff or his namesake restaurant, which he’d opened in 1984 at 700 East 17th Avenue. I went there and filled out an application. I was told to come back on Friday night to watch the action and learn a bit.

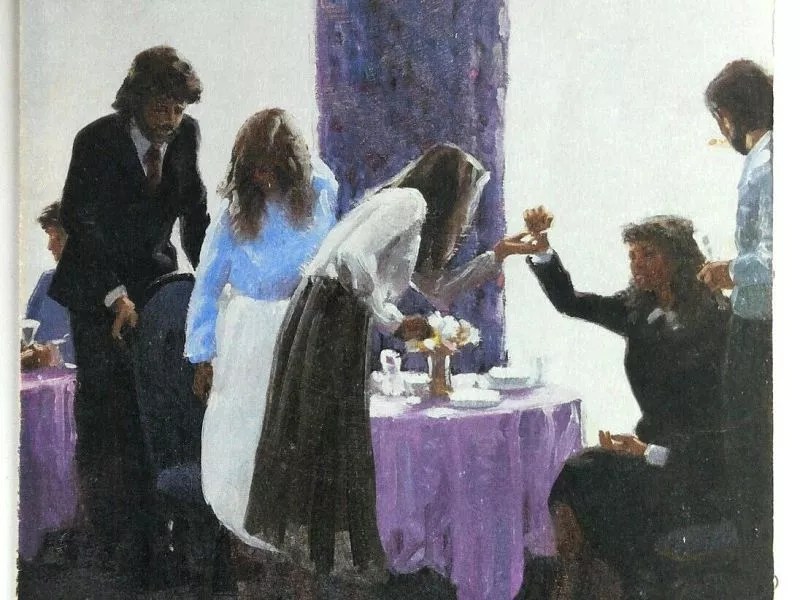

I sat in the lounge and watched as customers were seated in the elegant dining room, wrestled with their orders, then sopped up the juice left by the restaurant’s signature dish, the rack of lamb. Art on a plate.

Cliff would come by the lounge and tell me what was going on. The restaurant was really busy. Captains, back waiters and busboys pirouetted around the tables. It was art in motion.

If you’ve worked in a restaurant, you know that one door leads into the kitchen and one leads out. Cliff, helping his staff, zipped into the kitchen carrying a stacked oval busboy tray…and walked into a waiter carrying food out. Plates came crashing down, splattered food everywhere, a noisy mess. “Yeah, this is the place for me,” I thought.

I got the job. I knew to enter the kitchen through the proper door. I could clear a six-top in one trip. (I did that at least once.) The work was grueling. Cliff was at the front door and could see who needed their water glasses refilled, and motioned the staff to fill them. We did. People would cover their glasses when I walked up with the pitcher, saying, “I’ve had enough, thank you.” Cliff would say, “Fill booth 33’s water glasses.” “They don’t want any more.” “Do it.” Okay.

Soldiers have told me they don’t raise their hand when asked to volunteer. Raising your hand can bring hideous grief. Cliff was literate and clever. When he was in the Air Force, he became the chaplain’s assistant.

One day, when Cliff was angry with me for something, he traded me to the nearby Avenue Grill for a busboy and a dishwasher to be named at a later date. It was easier work than at Cliff’s. But I was traded back to Cliff’s for the holiday season, which ran from Thanksgiving to New Year’s.

In 1990 I was hired by the Rocky Mountain News to be the “Society Writer.” I was soon back at Cliff’s, now dining with socialites, and I’m sure my former co-workers spit on my food. They always had a smirk on their faces when serving me.

I was fired from the Rocky after 87 days, three days before my probation period ended. I went to Cliff to ask for my job back. He only had an opening for a valet. I took the gig.

So there I was, parking the cars of people I had just written about two weeks before. They wouldn’t even look at me. C’est dommage. I did my job, until one night I snapped my ankle falling off a curb and could not work.

I was publishing a monthly literary magazine called The New Censorship at the time and had no money for that, let alone rent. Cliff was a poet, and we’d often discussed literature. We bonded over that.

Broken ankle. No rent. I wrote Charles Bukowski, whom I’d published many times, and told him about it. He immediately sent me a $400 check to get by.

That money ran out, and I went back to Cliff. He said, “I need a secretary.” “I’ll be your secretary, Cliff!” Then I was. He even had a card made with my name and “Secretary” below it. I did the work. Arrived at 9 a.m. to take reservations, etc. My card pissed off so many people: “That Cliff Young, who does he think he is?” It was great!

Cliff would show up for work a little after I did. We made cappuccinos, talked about the events of the day and the week. Sometimes he would make me eggs and toast.

Cliff was a karate expert. He was always pulling moves on me that came within a millimeter of my nose. I didn’t blink. Cliff weighed about 250 pounds at the time, and if he hit me, I would have died.

One day I saw him pull up, and I hid behind the couch in the lounge. I jumped on his back when he walked by, and he threw me about six feet, into a table. It hurt, but it was funny as hell. It became a daily ritual. I’d hide when he arrived, then jump out and he’d go through karate motions. We got along very well.

Cliff hosted guest chefs at the restaurant, usually for three to five days. Tom Colicchio, Thomas Keller…and Julia Child. The famous undercover agent Julia Child. One morning, Child dropped a tray filled with racks of lamb, an entree that cost at least $30 three decades ago. She hummed some song while putting the meat back on the tray. Outstanding.

Sometimes John Elway and Mike Shanahan would dine with us the night before the game. Elway drank Scotch and smoked Marlboros. (Remember his two front teeth?) They didn’t talk to one another.

Cliff would visit each table, making sure his customers were happy. It didn’t matter if the customer was a quarterback or a rock star or a person celebrating his eightieth birthday. Cliff was imbued with compassion, a sense of humor and a sharp tongue. He was a cultural icon.

Stewart Jackson bought Cliff’s in 1993. I moved on to other projects and never again worked in a restaurant. Cliff Young moved to France, then came back to open other restaurants.

I thank Cliff Young for the things he taught me and the shit he gave me. Goodbye, Cliff, my friend. I miss you.

Ivan Suvanjieff and his wife, Dawn Engle, who founded PeaceJam in Denver in 1996, now live on the northeast tip of the Costa Brava, a dozen kilometers from France. See Suvanjieff”s latest project here.