Signs posted all around the CSU Spur campus at 4777 National Western Drive read, "Calling all taste buds!”

It's an intriguing offer: Sign up to become a CSU Spur taste tester to participate in various sensory science experiments. In return, you’ll get to try a variety of foods and receive snacks, and sometimes even cash, as compensation.

CSU Spur, an extension of Colorado State University, aims to bridge the gap between rural and urban communities through free educational programming. The campus is separated into three buildings: Vida (veterinary), Terra (agriculture) and Hydro (water). On any given day, there are groups of schoolchildren playing in the mock vet clinic, viewing the large-scale art installations and gawking at the living wall made up of 1,600 plants.

“[CSU Spur] is intended to showcase all these careers in food and ag and water and animal science...mostly for kids, so that kids can be like, ‘Wow, I did not know being a sensory scientist was a possible career opportunity for me,’” explains sensory manager Dr. Martha Calvert.

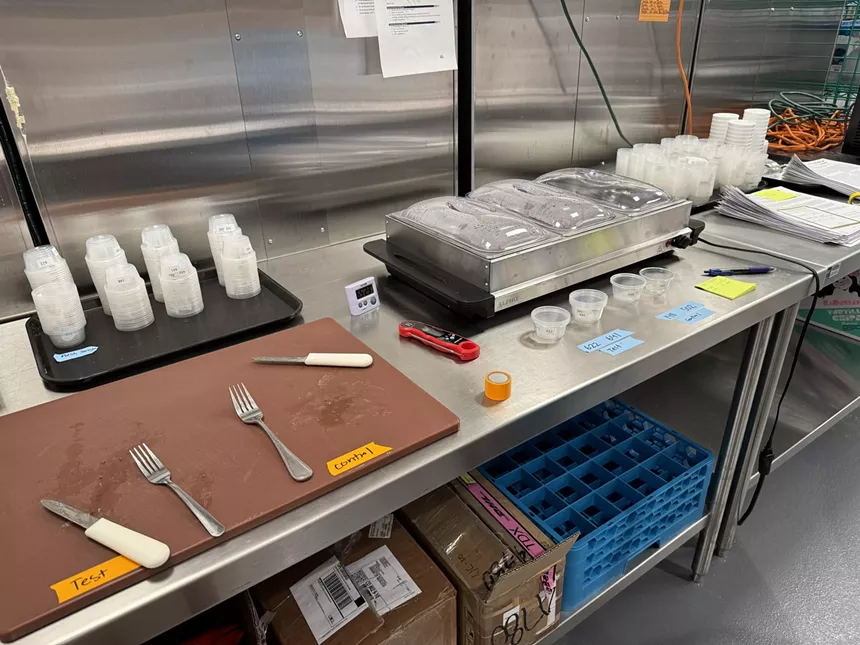

The Sensory Lab is part of the Food Innovation Center located on the first floor of the Terra building. It’s a small operation; Calvert is the only full-time employee. She’s supported by a part-time sensory technician and a group of volunteers. All of the testing is done in Sensory Booths, which are connected to the Food Innovation Center’s state-of-the-art commercial kitchen and can accommodate up to six testers at a time.

Food companies such as Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Danone, Arden Mills, etc., will approach Calvert to design, conduct and provide statistical analysis of different sensory experiments. “The Sensory Lab functions to support regional food businesses as well," she notes.

The three most popular types of experiments, Calvert says, are discrimination — evaluating whether testers can taste a difference between recipe formulations; acceptability — evaluating overall likability; and descriptive. "If you think about bags of specialty coffee and they always say, '[notes of] blueberries and chocolate,' descriptive testing allows us to get those tasting notes on a product,” she explains.

Sensory science as a discipline is relatively young. “It started during World War II, basically because soldiers weren’t eating their rations, and they needed to figure out why, so they started this nine-point hedonic scale which measures your liking of a product," Calvert says, requiring "control of the tasting environment as much as possible.”

The Institute of Food Technology describes sensory science as “a scientific method used to evoke, measure, analyze and interpret those responses to food products as perceived through the senses of sight, smell, touch, taste and hearing.” Sensory scientists view the perception of flavor as inclusive of all five senses, not just taste, where humans are the measuring instrument of flavor.

This type of testing is standard for food companies, where even a small change in recipe formulation, ingredient sourcing and/or packaging can impact millions of dollars of sales. That’s why they’ll pay places like CSU Spur’s Sensory Lab $4,000 to $10,000 to do rigorous testing before releasing a new product.

The Sensory Lab also helps with agriculture research for horticulture and biology professors who might, for example, be developing a new pesticide and “want to know if the pesticide is going to impact the corn’s flavor. And then how that’s going to carry through to the corn being sold at a farmers' market," Calvert explains. "Because a grower doesn’t want to implement a new pesticide if it’s going to make the corn taste horrible."

The Sensory Lab has tested vanilla extracts by baking them into Funfetti shortbread cookies; evaluated processed meat snacks like mini corn dogs, hot dogs, hamburgers and meatballs; and even run experiments on alcoholic beverages. In the future, Calvert hopes to incorporate more context testing, like playing different genres of music or using virtual reality to place testers in different environments.

Calvert spends the bulk of her time on logistics planning. “It’s almost like event planning, in a way. We have to make sure everything is perfectly set up, because the average consumer is coming in and doing taste testing, and they have zero idea what it is or that it’s a real science,” she says.

The day I visited, the Sensory Lab was paying participants $20 to complete a taste test of Polish sausages — a well-known grocery store had developed a new recipe and wanted to know if consumers could tell the difference between the current and new product, and whether they preferred one over the other.

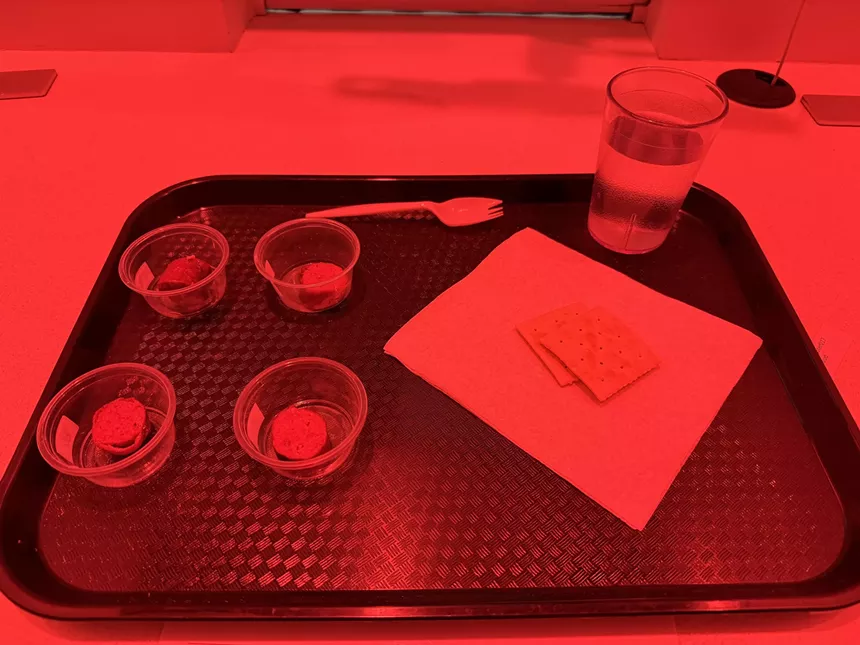

The Sensory Booths were awash in red light so participants couldn't discern any aesthetic differences between the samples, and there were signs instructing the group not to talk, play music or otherwise influence the ambience of the controlled setting. Inside was a long table with dividers between each station outfitted with a mounted iPad. A small window connected each station to the kitchen.

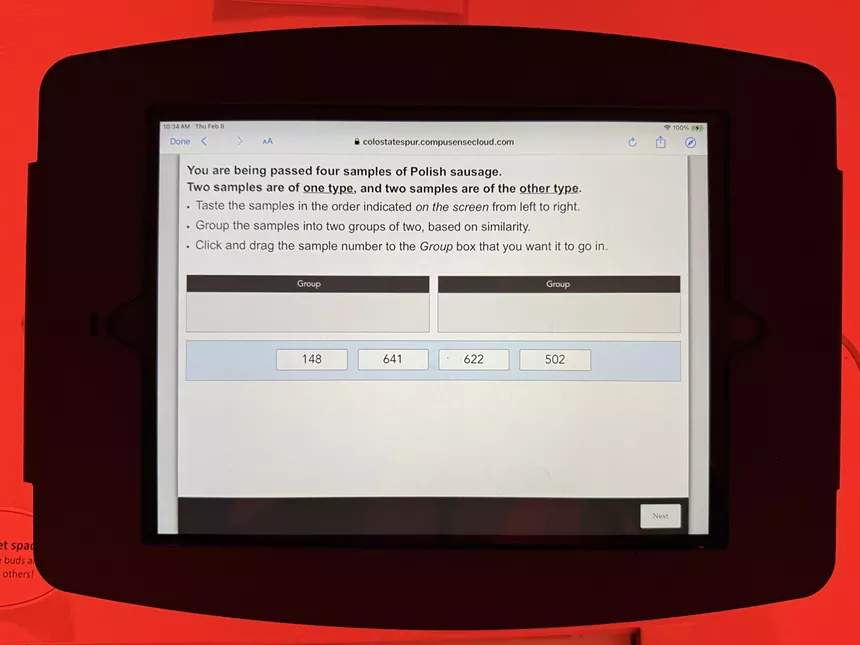

The screen prompted me to log in to the system and cycled me through a list of behavioral questions such as, "Are you the primary grocery shopper in your family?" and "How many meat products do you consume per month?"

Then the window opened up, and the technician, Rachel Waller, slid me a tray with four slices of Polish sausage in individual sample cups, a cup of water and some saltines. The iPad walked me through a tetrad test, asking me to group the sausages into two groups of two based on similarity in taste, and then asking for my opinion of the flavors of each group.

This specific test required at least 65 participants, so it was the only experiment that the Sensory Lab was running that week. Recruitment is still one of Calvert’s most time-consuming tasks, especially if certain experiments call for a selective group of testers. For example, the following week, the Sensory Lab was recruiting only individuals of Hispanic background between the ages of 22 and 45 for a microwaveable rice study.

Because of the ad hoc nature of the client engagements, the lab doesn't always know too far ahead of time what it will be testing. The best way to stay informed is to join the tester database by filling out this Google Form to get emails about upcoming experiments.

Calvert has also developed a panel training group program where “it’s only ten people that can sign up. It’s a group setting, and they taste samples and talk about all the different tasting notes,” she says. These sessions would last one hour, and “you’re essentially training your palate on a new product space. ... So one month might be wine, the next month might be chocolate. You practice with other people, and essentially you’re calibrating your mouth to be like others.”

Calvert hopes that training the palate and learning about flavor wheels will not only make participants better testers, but will help people discover a more intimate, healthier perspective of food. “I just think sensory science is really cool, because what made me fall in love with it was I was a baker before this for five years, and when you have a relationship with food and you really pay attention to how it tastes, it really changes your entire eating experience," she says.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Billboard - Slot Inline - Content - Labeled - No Desktop",

"component": "23668565",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "STN Player - Float - Mobile Only ",

"component": "23853568",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - 2x Rectangles Desktop, Tower on Mobile - Labeled",

"component": "24956856",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard to Tower - Slot Auto-select - Labeled",

"component": "17676724",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]