This vignette from Railroad Jerk's six-year history seems like a throwaway. But contained within the tale are the fundamental elements that make the band (Hall, bassist Tony Lee, guitarist Alec Stephen and drummer Dave Varenka) such a worthy sonic attraction--specifically, the artists' affinity for Americana, their capacity for spontaneity and their fascination with ambient sound. The deceptive simplicity of this style can be traced to the group's beginnings: Initially, Railroad Jerk consisted entirely of Hall and Lee, who played for spare change at Bowery subway stations as the trains rolled in and out.

The act's origins are recalled by a compendium of "natural" sounds--including a tin can rolling down a hill, a sack of cement being dropped onto a wooden floor and a drunk stumbling down a step--that the twosome compiled prior to Matador founder Chris Lombardi's decision to sign them to his then-nascent label. "We found our list several years down the line," Hall notes, "and I said, 'Hey, remember this? We should tell interviewers about this list, because they always ask questions about how we got started, and here's the documentation.' It's like the Constitution: It's not something we refer to and check up on all the time, but it's something we know about in the back of our minds." Proof of this last statement can be found on Railroad Jerk's latest long-player, The Third Rail: Whirring beneath the lurching skronk of "Middle Child" is an item from the roster--an electric drill. "I got it right on the first take," Hall boasts. "Did the whole song and didn't even practice. We said, 'Okay, let's do it,' so we pushed 'record,' and I did it through the whole song, and we never changed it."

At first the found sounds and samples that are woven into Railroad Jerk's discography seem merely trimmings pinned to the hem of their calamitous jug-band ditties. However, Hall insists that such flourishes often occupy a deeper place in the music's weft. "Some of it is planned out, some of it is an afterthought. Sometimes it can make the shape of a song. It can define a song in some ways, like the drill. That definitely wasn't just frosting. I had a four-track tape of that song that I made where I used the drill--so from the beginning we said, 'We've got to keep that drill in.'"

Other sorts of artistic stimuli are provided by Hall's hometown: On a typical day he can be seen walking the city's streets toting a notebook, a camera, a sketchbook and a tape recorder. "Two days ago I taped this car alarm that was going off that was going Beep! Beep! Beep!" he recalls. "Then there was this other sound"--he whistles like a distressed UFO--"and I just taped it. It lasted two minutes, and I can write a guitar part on top of that. We did the same thing with a construction site where there were a bunch of pounding jackhammers. And I had a PJ Harvey CD that was skipping on me, and I just taped it over and over and played guitar over the top of it and made it into a song. I'm really intrigued by that kind of stuff--just those natural rhythms that you can pick up anywhere." He insists that his appreciation for racket that others often find irritating is not simply a side effect of living in New York: "I was intrigued in college by other bands who were doing things like that--Einsterzeinde Neubauten and Tom Waits, who was using various blue-collar noises."

Despite the players' fondness for tape loops and power tools, they're hardly cold purveyors of industrial clatter. Rather, their grimy appropriation of rural musical traditions such as folk, country and the blues form the true body of their work, while their use of samples serves to make the music more immediate, providing it with a raw sense of location. When Hall and Lee were busking, the street echoed with ambient sounds--but in the insulated vacuum of a studio, the crackle of a needle on old vinyl, the garble of a radio or a trashcan beat lend dimension to musical idioms birthed by men who played their guitars alone on worn front porches.

Other sensibilities from the period when strangers flipped quarters into Hall's open guitar case have also survived. "We do stick with the idea of a non-electric set," he says. "Though I wouldn't call them 100 percent acoustic, there are songs on the new record that are done that way--completely live in a room where all the equipment is playing at low volume, with an acoustic guitar here and there, and the drums are pots and pans. That's definitely from our early days."

Still, Hall is careful to point out that Railroad Jerk is made up of revisionists, not revivalists. "I don't want to confuse us, in my mind or anyone else's, with the organic, countrified, folkified, laid-back feeling that was present in rock in America in the late Sixties and early Seventies. I think we're different, even though we've used all the terms to describe us that are the same. We try to mix things up with a little jagged edge here and there--an angular feeling rather than so smooth. We're not nature boys or anything." Hall laughs. "Nothing against Colorado..."

Another difference between Railroad Jerk and other acoustic-music looters is Hall's insistence upon maintaining a distance from his subject matter in an attempt to avoid what he views as the "pseudo-intimacy" endemic to the folk and country genres. "It's never been too hard, because my family never showed a lot of emotion--we had a really hard time saying how we felt and never hugged each other," he says. "There may be a conscious decision based on the way I was raised, or I may just feel uncomfortable getting that way. And I also get uncomfortable hearing other singers do it, because it sounds fake to me. Like you can't ever say fully, completely, 'I love you' without saying 'I hate you' or 'I'm not sure if I love you.' If I listen to George Jones, the lyrical content isn't what thrills me--but if I listen to the Modern Lovers or the Fall or the Birthday Party, the lyrical content does thrill me. What I think is good about country is the voice--it's so blatant and out front."

Like the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, the group with whom they share a Lower East Side practice space and several dates on their current tour, the Jerks frequently slap-box with the contention that a performer shouldn't play music to which he can't lay cultural or historical claim. This topic causes Hall's defenses to rise: "Kafka wrote a novel about living in New York, and he hadn't come here. What about Faulkner? Didn't he do that? Or was he only writing about poor whites? What if he wasn't poor?" He subsequently admits that he grapples with such issues "all the time--but I'm at peace with myself, because there's no way we're identifying with black culture. The heroes that we draw from are just as much white as they are black. Woody Guthrie was white, Jimmie Rodgers was white, Hank Williams was white. They're all Southern--and I guess we're Northern...But Bob Dylan was from the north, but he was aping them, too. Maybe."

So why do so many people wish to affix zip codes to inspiration and imagination? "They're just inundated with politically correct ideas without even thinking," he responds. "I don't think it has much to do with territorialism. I don't think it's a natural feeling. I think it's a trend that people have to think through. There's something to be said for both sides, but almost anything you do is authentic. If you do it honestly, then it's authentic. And nothing we're doing is dishonest. I never sing with a twang, and I purposefully don't. I have no reason to. I have a problem with the way G. Love sings, but I like some of his music.

"People are so worried about stepping on certain things, but as soon as you make those definitions, it's so confining in the first place. All those accusations about Elvis Presley ripping off black people just kills me. Musically, roots go back in all different directions. I don't have anything negative to say about black culture, but the idea that someone is stealing from them, I don't understand. Music is a grab bag--and to make a collage is anyone's to do."

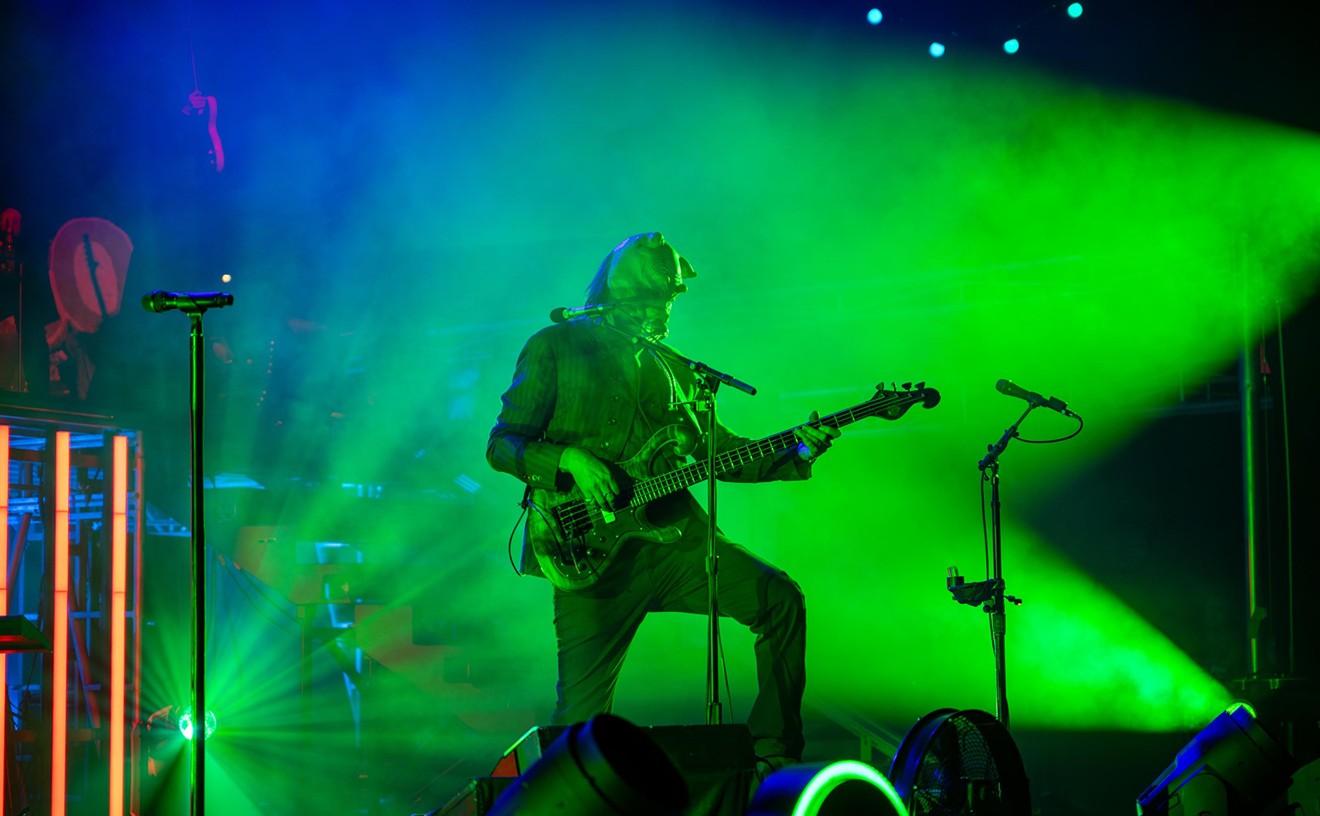

Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, with Railroad Jerk. 8 p.m. Tuesday, November 12, Ogden Theatre, 935 East Colfax, $11-$12, all ages, 830-2525 or 1-800-444-