Anthology is hardly the first compilation of its kind to get the balance between art and commerce so wrong. The modern boxed-set era was inaugurated by Elvis Aron Presley, an opus issued in 1980, three years after the King toppled off his porcelain throne, that stuffed eight (count 'em, eight) LPs with assorted flotsam so uninteresting that even fanatics desperate for any piece o' Presley tuned out in droves. Moreover, the past several years have seen plenty of big-ticket projects that attempted to disguise the unessential nature of the music at their core with lavish packaging, weighty essays and record-company puffery.

But whereas padded products such as 1997's The Doors Box Set draw from the act's entire oeuvre, thereby providing a certain historical perspective almost in spite of themselves, Anthology is hobbled by the limitations imposed by its time frame. To put it politely, Lennon's solo efforts were infinitely more erratic than his material with the Beatles. Following a decade (the Sixties) during which he seemingly could do no wrong, he managed to produce one indisputable masterpiece (1970's Plastic Ono Band), one fairly strong platter (1971's Imagine) and a handful of other records that simply can't compare to his finest inventions. As a result, Anthology emerges as a monument to a period of creative confusion filled with alternate renditions of tunes that often weren't that seminal in the first place.

In her liner notes, Yoko Ono doesn't come right out and admit as much, but she hints that the volume is more a biographical slice of life than a batch of ditties to which buffs will want to return again and again. "This is the John that I knew, not the John that you knew through the press, the records and the films," she writes. "I am saying to you, here's my John. I wish to share my knowledge of him with you." She also confronts the "professional widow" issue that's dogged her since Lennon's death. According to her, "I continue to distribute John's work for many reasons: first for John, who was a communicator/artist/musician, who would have liked for his work to go on; second, for the fans who want more, more and more; and third, for the family, including myself, who are proud of Father John's work and would like to see his work out there for a long time to come."

The fallacies inherent in this argument aren't tough to locate. Lennon's music will be cherished for generations to come whether Ono cleans out any more of her closets or not, and his admirers don't deserve to be exploited even if it's okay by them. In addition, a lot of what's on Anthology doesn't exactly fit the definition of "work." An inventory of the CDs turns up the following:

A coy nineteen-second snippet of dialogue between John and Yoko that revolves around the word "fortunately" (disc one)...

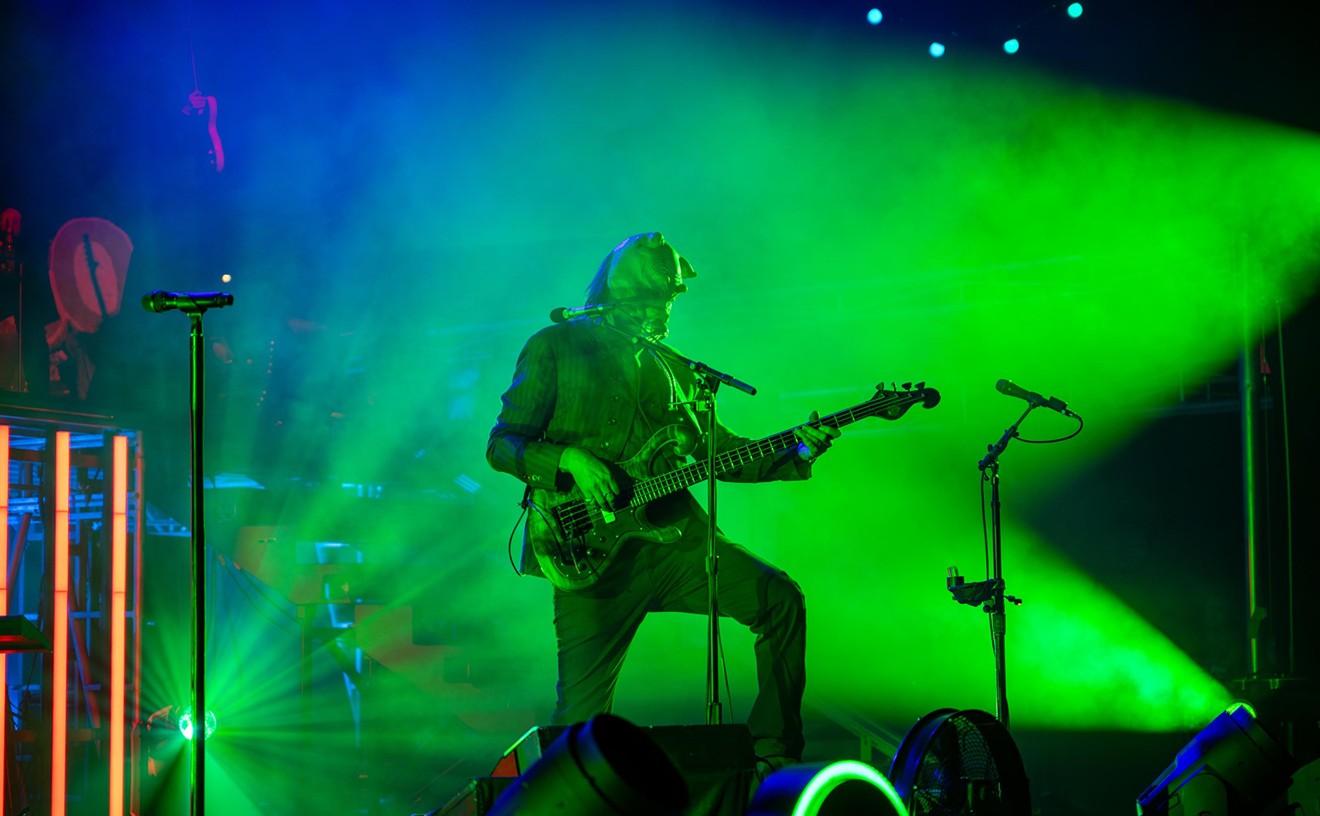

Geraldo Rivera sounding frantic while introducing Lennon and Elephant's Memory at Madison Square Garden in 1972 (disc two)...

A conversation about activist John Sinclair (profiled in "Surviving the Sixties," August 7, 1997) heard first during The David Frost Show (disc two)...

Jerry Lewis leading a "John/Yoko" chant during his 1972 telethon (disc two)...

Twelve seconds of John and Yoko goofing on "As Time Goes By" (disc two)...

Several examples of crazy studio badinage involving John and amped-up super-producer Phil Spector that was captured on tape in 1973 (disc three)...

Four different tracks in which Lennon comically imitates Bob Dylan (disc four)...

A pre-kindergarten Sean Lennon singing part of "With a Little Help From My Friends," happily declaring that he likes guitar-playing best when it's loud and asking when his parents rented their home (disc four)...

Some of this ephemera is mildly entertaining--particularly Spector's antics. (At one point he explodes, "What is that tweeting bird out there? For God's sake!") But most of it is suggestive of the music videos Ono assembled out of old home movies in order to promote Milk and Honey, a 1984 album dominated by some of Lennon's rough sketches. There's a certain creepiness about her continuing need to make her beloved's image conform to the model she's constructed. A more objective outside party would delve into the contradictions that made Lennon among the most fascinating public figures of the past half-century. Ono, by contrast, sands off the rough edges, turning Anthology into yet another variation on a tale she's been telling for nearly twenty years now. It's a fine story, certainly: Who wouldn't be cheered by a narrative about a searcher who ultimately discovers that love really is all you need? But anyone hoping for more insight than that is out of luck again.

Musically, most of Anthology's meat can be found on the first CD. None of the versions of songs that ultimately turned up on Plastic Ono Band outstrip those that made the final cut, but they're so naked and emotional that listeners probably won't mind. "I Found Out," heard on a home recording, is drenched in hoodoo reverb that echoes with danger; "Isolation" is delivered with poignant gentleness; and "Remember" practically collapses at its midpoint, when Lennon starts guffawing about the saminess of its rhythm. The Imagine tunes are somewhat less intriguing by comparison--with the exception of a surprisingly slinky "How Do You Sleep?" (Lennon's attack on old buddy Paul McCartney)--and oddities such as "God Save Oz" and "Do the Oz" don't add up to much. But of the four discs here, this first one provides the most pure sonic pleasure.

It's all downhill from there, and while the decline isn't precipitous, it's impossible to ignore. The second CD pulls together music from Lennon's political period, and it dates badly. "Attica State," about the infamous prison riots, is dragged down by lyrics that are numbing in their obviousness ("Join the movement/Take a stand for human rights"), and "Bring on the Lucie," "Luck of the Irish" and "John Sinclair" suffer from the same malady. "I'm the Greatest" and "Goodnight Vienna," two tunes Lennon wrote for Ringo Starr, are more tolerable because they sound lighthearted and off-the-cuff, but remainders left off the 1973 Mind Games album feel watered-down, tentative--a quality they share with the sloughed-off "Whatever Gets You Through the Night" that appears near the top of the third disc. Fortunately, outtakes from Rock 'n' Roll, a collection of throwbacks that hit stores in 1975, have more juice in them. Lennon at least sounds like he's having fun during "Be Bop a Lula," "Rip It Up/Ready Teddy" and "Move Over Ms. L," and he gets off his best joke on a parody of "Yesterday." In a BBC announcer's voice, he intones, "Suddenly, I'm not half the man I used to be/'Cause now I'm an amputee."

The last of the set's discs is culled primarily from the sessions for 1980's Double Fantasy, a John-and-Yoko collaboration released shortly before Lennon was shot. At the time, grief-stricken rock aficionados dubbed it a classic, which was understandable but unjustified: Ono's songs on it are better than usual, but that doesn't mean they're all that good, and Lennon's compositions generally settle for merely pleasant when he was plainly capable of so much more. That said, full-band run-throughs of "Nobody Told Me" and "I Don't Wanna Face It" are lively, "I'm Losing You," featuring three members of Cheap Trick doing what they do best, has its fiery moments, and "Beautiful Boy" is as sweet as it ever was. Too bad these entries are surrounded by inconsequential demos of "Life Begins at 40," "Woman" and "Watching the Wheels," as well an overdose of curios that belong in a trunk in Ono's attic.

Would Lennon have given his blessing to the merchandising of such detritus under his name? Hard to say. From all available evidence, he loved Ono unreservedly and might well feel that her stated reasons for putting it into a box and selling it for around $60 a pop are excellent ones. But anyone who wants to revel in Lennon's musical accomplishments would be far better off spending the same amount of money to purchase copies of Rubber Soul, Revolver, The Beatles (aka The White Album) and, yes, Plastic Ono Band. As for those of you hoping to get your paws on Lennon's answering-machine messages, you'll just have to wait for Anthology 2.