Cori Redford

Audio By Carbonatix

Cuddling was not something Jen Ikuta instantly embraced.

“The first time someone told me that I should to go to a cuddle party, I was like, ‘You’re batshit. You’re crazy. I’m not going where a bunch of strangers are, and they’re all going to want to touch me. I’m not doing that,'” recalls Ikuta, today one of a growing group of Denver-based cuddle therapists. “I was raised by a coke and meth addict. I was raped at twelve. Like, actually, no, I’ve never had any kind of safe physical touch.”

Cuddling changed that. “They convinced me that I could just try it without being touched. I could just sit in the corner, and I could be in this community with other people who believed the same things about safe touch,” she says. “I would not be touched if I didn’t want to be, and everyone had to ask for a verbal yes or a verbal no. I could be in the cuddle group as much as I wanted or as little as I wanted. So I went, and it was incredible.”

Cuddling comprises a community, but it is also a growing profession. People signing up for cuddle parties pay – $30 is common – for an event that includes a professionally-led “welcome circle” of sixty to ninety minutes, during which topics such as consent, etiquette and the benefits of cuddling are discussed.

For additional fees, a cuddling session can be private and one-on-one, often in the home of the cuddler. Professionals advertise on websites such as Cuddlist, Cuddle Comfort and Cuddle Companions, where their profiles feature detailed outlines of services offered, plus photos of the practitioners themselves. Rates vary, but the standard is $100 per hour with a two-hour minimum. On most sites, a strict policy of platonic touch is spelled out. Very few professional cuddlers – who usually prefer to refer to themselves as cuddle therapists or cuddle practitioners – identify as male; the overwhelming majority identify as female, and there is a growing number of trans and gender-fluid therapists. Their clientele, on the other hand, is evenly split between genders.

Following her cuddle epiphany in early 2020, Ikuta was hooked on the feeling. “The next day,” she remembers, “I texted my friend and said, ‘What was in the drinks? It was a sober event, right? What did you dose the water with? What am I on?’ These cuddle parties are always sober events. I was experiencing all of my body’s natural hormones that are released when safe touch is exchanged. You have the serotonin and the oxytocin and the dopamine. You have all of these beautiful things that you likely have never experienced before.”

Some are physical, some emotional.

“The number one thing that happens at a community cuddle with only women is everyone’s bawling,” Ikuta says. “Everyone is crying because where in the world can we find a safe place to touch each other like this? Where else can this happen in a completely platonic, nonsexual way?”

Jen Ikuta is a professional cuddler.

Jen Ikuta

Men are just as much in need of a cuddle, she notes: “Paternal touch is entirely out of the question in our culture. In men, touching other men is absolutely frowned upon or else you’re called gay. And we don’t see enough of the safe male touch. So it leads to this loneliness, right? And we see it from children, starting as young as six years old. We see this loneliness, all the way up until we’re seeing elderly people die alone.

“One of my favorite professional cuddlers that is a male is in North Carolina, and he’s a hospice nurse,” she adds. “He came into cuddling because he noticed that all of these dying people just wanted touch. They knew they were on their way out, but they were never surrounded by people. And he was like, ‘Well, of course I can do that. I can climb into bed with you right now.'”

After her first cuddling experience, Ikuta wanted to become a practitioner herself. But COVID set in, and another two years passed before she was able to set up her own practice.

The social distancing necessitated by COVID only added to her passion for cuddling, though. For her, cuddling is a form of connection that’s missing not just on a personal scale, but on an anthropological one.

“We’re all living independently, and traditionally humans have always lived together in tribes or groups or communities or town centers,” she says. “We don’t have that in our culture. As a society, as a whole, we don’t value togetherness as much as in generations past or in other cultures or in other countries. So we see an exorbitant amount of loneliness.”

That loneliness, according to Ikuta, has exacerbated everything from heart disease to chronic fatigue syndrome to alcoholism – basically, pathology on a systemic level. Science bears that out. Numerous studies have determined that human touch has profound health benefits; according to a 2021 article in the Economist, medical researchers around the world agree on touch’s ability to flood our bodies with a cocktail of anxiety-dampening, inflammation-soothing hormones, including the serotonin, oxytocin and dopamine cited by Ikuta. Babies that are touched more than others gain weight and develop cognitively at a faster rate. There’s even evidence that the cell-stimulating power of touch can help combat cancer and HIV.

Conversely, a dearth of touch can cause lingering, if not lifelong, problems.

“A lot of the trauma that I see in my clients comes from people not having decent parents and not getting the touch they needed growing up,” she says. “They have a lot of childhood trauma. So I will hold them in certain positions, like the grandma position. The grandma position is where I’ll put my client right along my hip, and I’ll hold them while they interlace their hands underneath my legs. And they hold on to me like they would hold on to their grandma’s leg while she’s cooking in the kitchen.

“The client will ask me, ‘Why is this so healing? What’s happening?’ It’s epigenetics. It’s your cells remembering things that may have happened generations ago. They’ll be like, ‘Oh, my gosh, I did hear a story once from my mom or my auntie about how my grandma used to cook in the kitchen all the time. I never experienced that. I didn’t have that, but I know that it’s in my genes.'”

Ikuta says that 90 percent of her clients are autistic, as she is herself. She also sees a large number of amputees and people who use wheelchairs – “because,” she says, “for whatever reason, societally, they tend to get even less touch than the average individual.”

Ikuta’s solution? Turn to an expert.

Getting in Touch

“When was the last time someone touched you – not by accident, not out of obligation, but with care and intention?” Ikuta asked during her address at the Human Connection Conference in Denver in November. “For many people, that question brings a moment of stillness. Maybe it was a hug that felt like home. Or maybe, like so many of us, it’s been far too long.”

In the world of professional cuddling, consent is more than a buzzword. It’s a complicated dynamic to navigate, even in a structured setting like a cuddle party or private session. But it can also teach clients to understand their own boundaries in a safe, objective space – as well as give them the tools to communicate consent more clearly to partners.

“Consent is a volleyball game,” Ikuta says. “It’s not just a baseball game where you hit the ball out of the park. It’s not going to happen that way. You have to be able to have this back and forth. Like, ‘Ooh, I changed my mind. I don’t like that anymore. But we’re staying in it.’ We’re not removing ourselves entirely and saying, ‘No, fuck you. I don’t want to touch you ever again.’ We’re saying, ‘This has to shift if I’m going to love you and love me at the same time.”

Heather Newhouse is just as centered on consent. Billing herself as a somatic practitioner and consent educator, she earned a degree in sociology and served a stint at Planned Parenthood and at a massage salon before setting up her own holistic practice in Denver.

“I come at cuddling and sex education and intimacy work through a lens of sociological learning,” Newhouse says. “I’ve always been a very empathetic, sensitive person, a very affectionate person since a very young age, but I also think I’ve always been an activist of sorts. At Planned Parenthood, I learned a lot about informed consent and teaching people about their bodies. I started to see how amazing it was to be able to support people that way. I’m someone who was socialized as a woman, and there’s a lot that comes with that in terms of body autonomy and consent issues.”

As Newhouse sees it, those issues are most severe and dramatic in cases of sexual assault; accordingly, trauma-informed cuddling is one of her areas of focus.

“There’s a lot that can happen in day-to-day life where people are touched without their permission, where people endure and tolerate touch,” she says. “But there’s a lot of good neurochemistry that happens when you feel safe and connected with another human being, when you’re in close physical proximity. And that is universal. When you see a professional cuddler, they’re facilitating a space for you to explore touch platonically. There’s a lot of room for people to experience and learn about what safe touch is, both giving and receiving. If cuddle sessions are facilitated by someone with enough knowledge and awareness and ethics, they can be really transformational for people. Touch is incredibly healing. We see that with massage therapy, and we can see that hopefully in personal relationships, but in general, our culture is so touch-starved.

“For most of us,” she continues, “our systems are so stressed, whether it’s from sexual trauma, from physical trauma, from emotional trauma, from neglect. I’m not trying to heal anybody anything. I’m just trying to support them in expressing what they want and need through touch. How often do we get the opportunity to do that with another person that isn’t already close to us, like romantic partners and family members? When you go to a professional, you don’t have to worry about that stuff the same way.”

Paying someone to hold you, however, does carry its own set of concerns.

No, This Is Not Sex

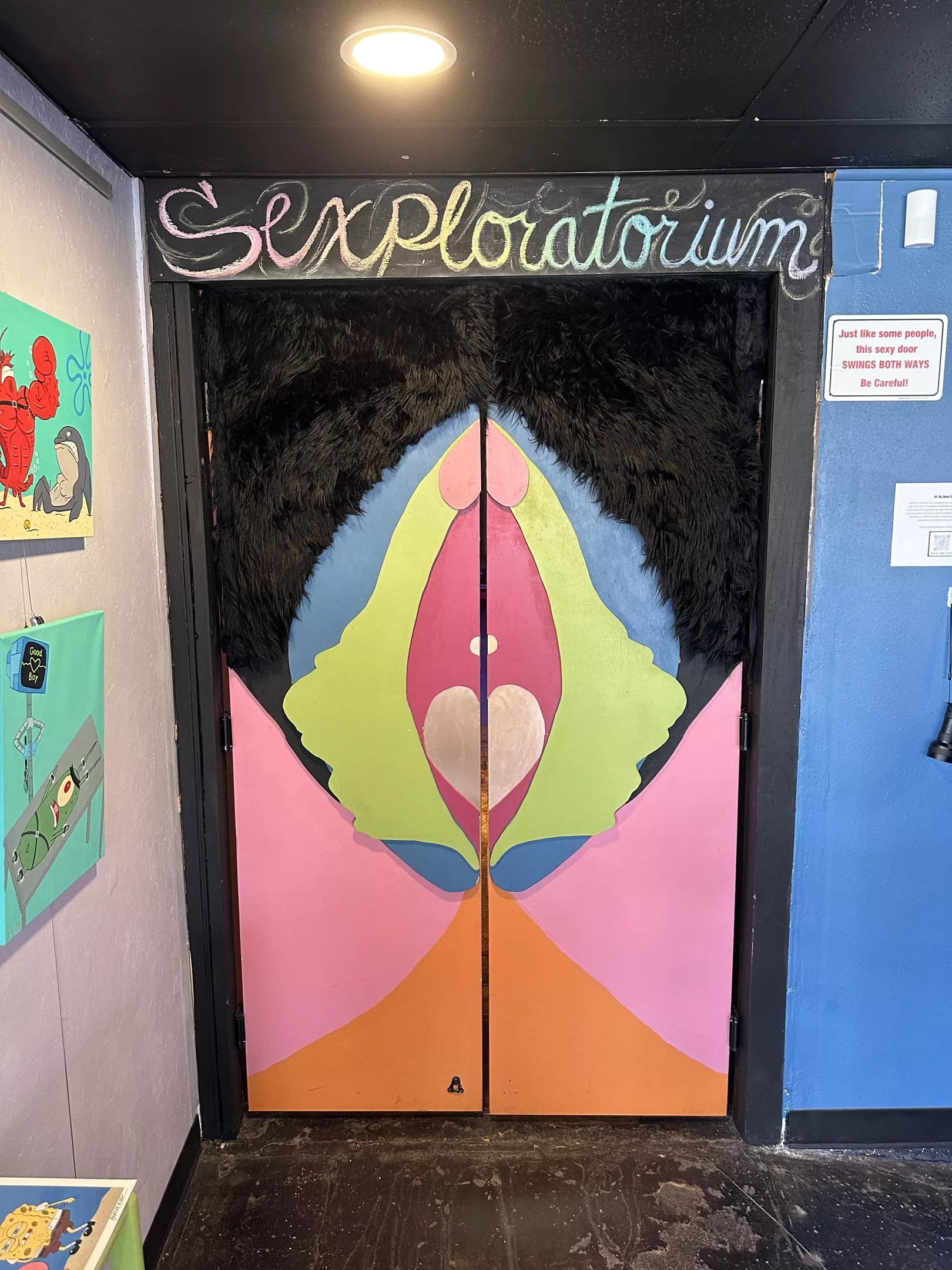

“We’re not allowed to talk about sex,” says Fawn O’Brietzman, co-owner of the Sexploratorium and the Museum of Sex at 1800 South Broadway. Although she doesn’t practice professional cuddling, as a sex educator she’s very familiar with the cuddling community. “Sex is still a really taboo subject. We’re not allowed to really learn about it. We’re shielded from a lot of things, and because of that, we’ve sexualized a lot of things that weren’t really sexualized in the past. So when it comes to touch itself, all we have learned is how to say no.”

A former psychology professor at Red Rocks Community College, O’Breitzman opened the Sexploratorium with partner Casey O’Breitzman in 2023 as a community space for education and positivity. A year later, they unveiled the Museum of Sex inside the Sexploratorium, and their calendar is filled with events that aim to facilitate conversation and openness, both personal and societal, in regard to sexuality. And a lot of that, she says, has to do with touch.

“The only thing we understand is that as children, adults shouldn’t touch our private parts, and that’s about all the learning we get when it comes to touch,” O’Breitzman says. “And so it’s really hard for us to open up as adults and say, ‘I want this kind of touch in this kind of situation, and here’s how I can talk about it, and here’s how I can put up that boundary, and here’s what I do if that boundary is not met.”

Establishing certain boundaries is pivotal to the practice of touch, she says, but breaking down other boundaries is just as vital.

“Masters and Johnson, when they were doing all their famous sex research, they looked at the problem of solving sexual dysfunction,” she explains. “And one of the things they found was that if you engage with patients in a therapeutic way, you can actually go a whole lot farther than if you just talk to them about it. So they created what’s called sex surrogate. The sex surrogate’s job is to physically engage with the person in a sexual manner, but with a guiding therapeutic intent.

“That became quite scandalous in psychology, of course,” she continues. “But I liken the difference between a psychologist and a sex surrogate to the difference between doctor and a physical therapist. Your doctor doesn’t really get into the nitty gritty with you if you’re recovering from an injury. They check on you, then they’re like, ‘Okay, you’ve gotten this much better or this much worse, and here’s what we’re going to do.’ They make a plan. But it’s the physical therapist who actually does the hands-on treatment.”

Adds O’Breitzman: “In a platonic manner, a professional cuddler is very much the same as a physical therapist or a sex surrogate. They are fulfilling the needs of a person who cannot get that need met in other ways. Like, maybe that person is extremely agoraphobic and can’t leave their house. But they still need touch. We are mammals. We die without touch. This has been shown again and again. My favorite example is when orphans in a nunnery were dying at a 50 percent rate. They assigned one nun to do nothing but hold babies, and the death rate went to zero. But as adults, it’s weird that there’s a stigma against getting that kind of care. I can pay somebody to talk to me about my deepest, darkest, most private moments, but giving me a hug is beyond the pale.”

No official cuddling at the Sexploratorium.

Teague Bohlen

In the eyes of Colorado law, however, the boundaries around paying someone for touch are very clear.

“The main difference between professional cuddling and prostitution comes down to whether a sexual act is involved,” says Jesse Hall, an attorney at the Denver criminal-defense law firm of Masterson Hall. “Professional cuddling typically involves nonsexual physical touch like hugging, holding hands, or snuggling. Thus, if a client and a professional cuddler engage in any sexual activity that is defined as a sexual act under the law, like sexual touching or penetration, and money is exchanged for that activity, then it would cross the line into prostitution.”

Then again, Hall says he’s never heard of a criminal case being brought against anyone in Colorado that involved professional cuddling.

“It seems professional cuddling tends to not attract the same level of scrutiny or attention as sex work, since the services are marketed and performed in a way that emphasizes emotional connection and platonic physical touch,” he says. “That may be one reason it hasn’t been on the legal radar in the same way that traditional sex work has. Of course, the more public or visible this industry becomes, the more likely legal or regulatory questions might emerge, especially if it’s viewed as more adjacent to the sex work industry.”

No Colorado lawmaker has ever proposed legislation that involves professional cuddling, either. “Cuddling is the Wild West,” Ikuta notes. “It’s unregulated. The Department of Regulatory Agencies hasn’t gotten its sticky fingers in it yet. But that also means there’s no wide understanding of what professional cuddling is. It’s not like getting X, Y and Z training as a massage therapist, where you get licensed by DORA.” Indeed, while DORA’s website does detail its entire program for massage licensure and board review, it makes no mention of cuddle therapy.

When Ikuta decided to study cuddling as a profession, she was put on the path of training by her birth doula, who had previously become certified as a pro cuddler through Cuddlist. Although the website doesn’t require cuddlers who advertise there to be trained or certified in any way, the elective training program offers in-house certification after six months of self-paced, at-home classes. CTI-certified cuddlists are highlighted as such on their Cuddlist profiles, granting them greater appeal to potential clients. The price for the lessons is $799, and it includes instruction in cuddling modality – the how-and-why of cuddling therapy – as well as advice in launching a cuddling career.

Still, turning cuddling into a full-time profession, as Ikuta has, is rare. “It helped that I did a lot of mentorship with Kassandra Brown, who ran the first cuddle party I went to,” she explains. Ikuta now collaborates with her mentor on many cuddling events. “So I had hours and hours and hours of experience in the field before I started doing it professionally.”

Despite the unregulated status of professional cuddling, Ikita does require new clients to sign a waiver that states in all capital letters, “NO SEXUAL ACTIVITY SHALL BE PERMITTED.” Also, clients must be at least eighteen years old; shorts must cover the top half of the thigh; breast and genital contact are forbidden; no bodily fluids, including saliva, may be exchanged; and both client and practitioner must be completely sober at the time of cuddling.

“I’m very clear with my new clients that I am not a sex worker,” Ikuta says. “I don’t want to attract those clients. I’m not willing to do that in exchange for money or anything else. One of the biggest issues in this industry is women saying that they are professional cuddlers, but they’re sex workers. There are a lot of misconceptions about cuddling, a lot of snap judgments. I really want the cuddling community to be a space where we can help heal the epidemic of loneliness. I don’t even know where it stems from exactly, but we are constantly being told that humans are hurting other humans on the news, on billboards, by friends, on social media. But we’re rarely told how beautiful and amazing we can be with each other.

“If you are human, you should be cuddled,” she adds. “End of story.”