Amanda Pampuro

Audio By Carbonatix

Imagine engineering students writing poetry.

“It’s almost a paradox,” says Danny Long, an instructor in the Program for Writing and Rhetoric at CU Boulder. Long’s Radical Science Writing course challenges upper-division science students to write and illustrate children’s books, design eye-catching posters, and craft poems about the basic elements of the universe.

Long notes that the origin of the word “radical” means “roots.” “The idea behind radical science writing is we take the roots of scientific communication, but then we use them in slightly new, unorthodox ways,” he says.

The result? Poetry.

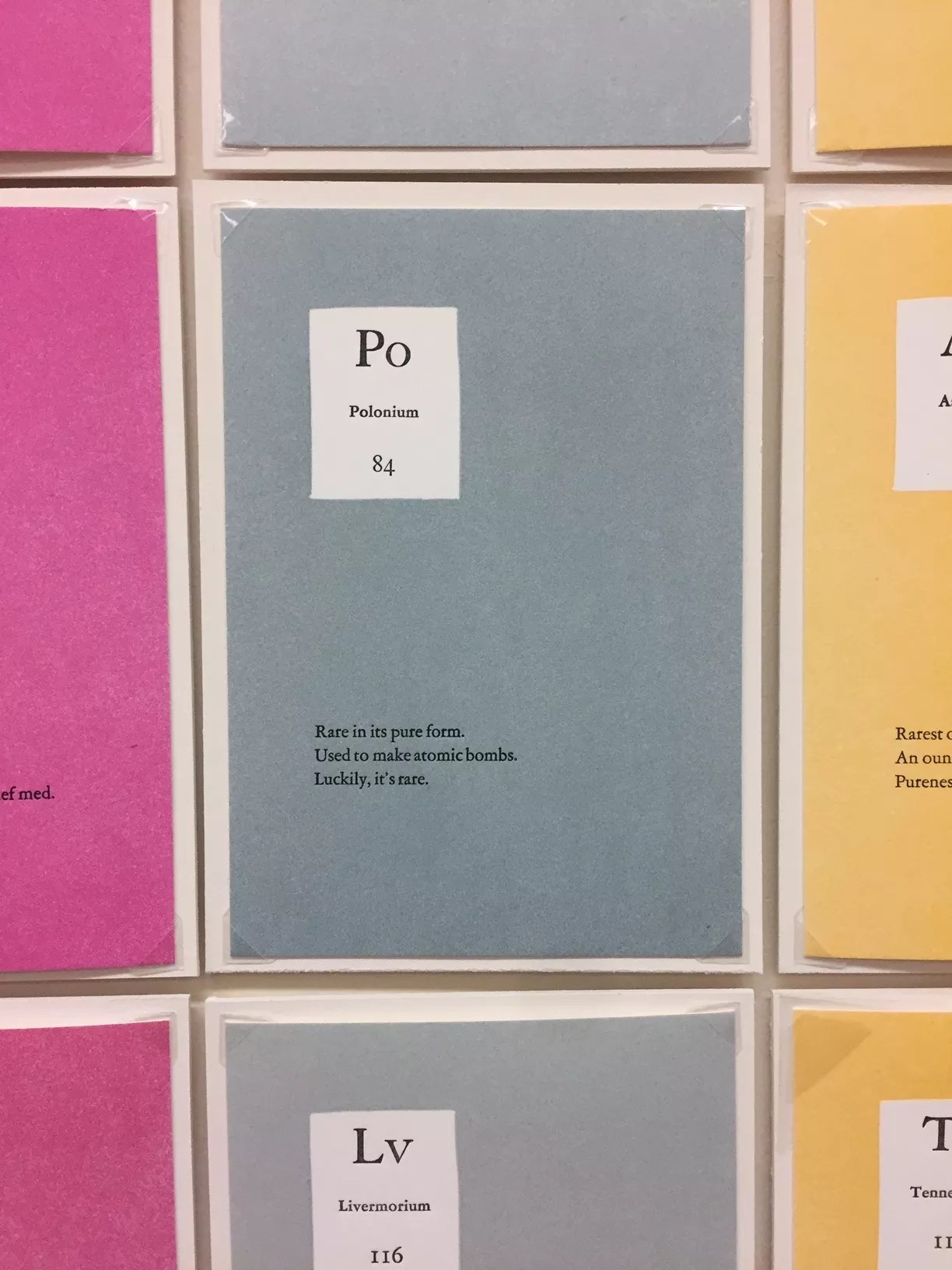

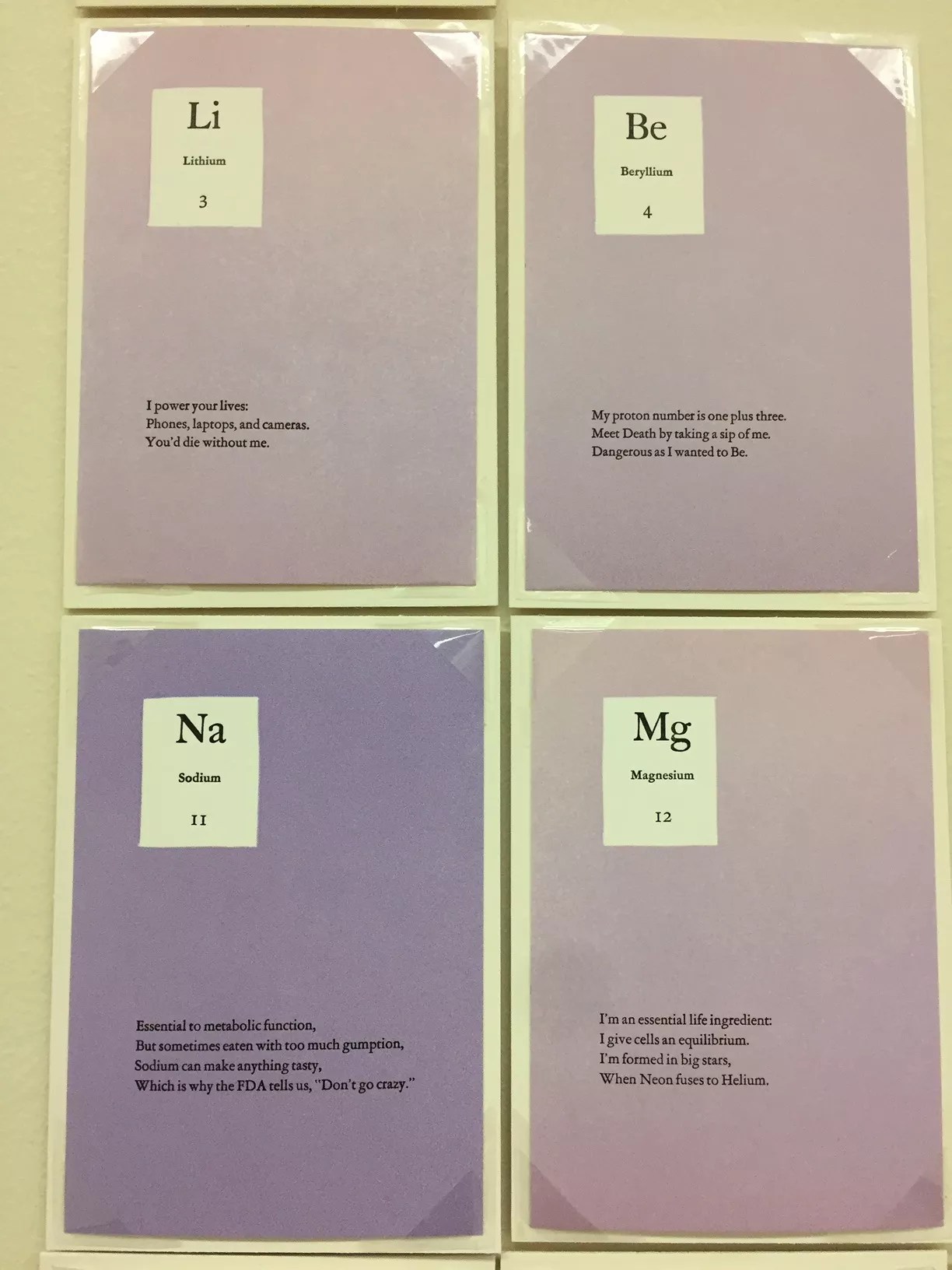

Last semester, Long’s 39 students created The Poetic Table of Elements, brief poems identifying each element by its characteristic, history or lethality. Nine copies were created. Funding for the project came from the Program for Writing and Rhetoric and CU Boulder’s Grand Challenge initiative.

Science students at CU Boulder wrote, designed and printed The Poetic Table of Elements.

Amanda Pampuro

In their poems, students write about the elemental origins of stars and serious historical disputes; they play on the paradox that a substance can cause cancer in one context and cure it in another. A great many of the single-stanza poems highlight the number of elements that are deadly to humans. The poet-engineers describe carbon monoxide poisoning and the atomic bomb cocktail.

“I’ve taken years of chemistry. I’m actually a pre-med student. But I had never even heard of one of the elements I had been assigned,” says Sarena Gill, a student who found herself stuck with moscovium, known to Call of Duty players as Element 115. “I did some research, and it turned out that in one video game that’s really popular, this element was the cause of a zombie apocalypse, so…I got to take something I would have never really thought of when approaching the elements and put it into the poem.”

Science students at CU Boulder wrote, designed and printed The Poetic Table of Elements.

Amanda Pampuro

An experiment in itself, the radical science curriculum attempts to transport the student steeped in modern academia, where disciplines are segregated into silos, back to a time when knowledge was multi-faceted. After all, naturalists Robert Hooke and Charles Darwin employed careful drawing and poetic prose when delivering their findings to their audience.

“The things that motivate my assignments are joy and wonder,” Long says. “What kinds of writing will give my students joy? What will give their intended audience joy? What will engage them in research that sparks their sense of wonder? What might they write to spark a sense of wonder in others? Joy and wonder are the ideal – and, I’d argue, noble – consequences of radical science writing.”

Rather than just type their text into Microsoft Word and laser-jet it onto sheets of copy paper, Long’s students printed their works with hand-set type, using a century-old Sigwalt Nonpareil No. 23 press, onto hand-dyed Arnhem 1618 heavy 320gsm paper. They carefully chose three fonts: graceful Garamond, ornamental Caslon, and elegant Centaur.

Science students at CU Boulder wrote, designed and printed The Poetic Table of Elements.

Amanda Pampuro

The students received technical skills from three university librarians: Gregory Robl, Susan Guinn-Chipman and Julia Seko. Robl and Seko are also members of the Book Arts League in Lafayette.

Seko, who studied both math and English, says this project has helped students realize that creativity isn’t some divine occurrence.

“You realize, being creative, there’s a process,” Seko says. “It’s not like something is coming down on you from on high. It’s a process, just like calculating things, just like developing or studying properties of things. You are doing all the same things.”

While you can read about printing in a book, Robl says the craft cannot really be taught without being experienced.

Science students at CU Boulder wrote, designed and printed The Poetic Table of Elements.

Amanda Pampuro

“This is one of the things the students really enjoyed: physically talking about how the materials work, because you’ve got ink and metal and paper,” says Robl. “I want you to get a feel for how hard you have to push on this [press] to get it to print [the way] you want it to print, because that is something nobody can tell you how to do.”

Additionally, Robl chose thick card stock so each letter would leave its bite, giving a three-dimensional tactile experience.

“In traditional letterpress printing 200, 300, 400 years ago, when you’re printing a book, you want the paper to just roll across the type and just leave that mark so that when you print on the reverse, you’re not seeing that relief. Now, people love that in letterpress printing,” Robl says. “I wanted them to have that experience, so when they have their cards, they can touch them and they can feel that.”

The Poetic Table of Elements is on display on the third floor of CU Boulder’s Norlin Library, 1720 Pleasant Street, through March 31. For a full list of hours, go to the Norlin Library’s website.