Shannon Galpin

Audio By Carbonatix

In spray paint, on an unassuming wall in the 2700 block of Larimer Street that’s part of the American Bonded building, a debate is raging over gentrification, gender, race and freedom of speech. Artists have painted accusations of censorship. They have satirized, slammed and celebrated each other, while taggers and vandals have weighed in with incoherent gestures of destruction.

Along the way, big questions have come up: Whose walls are these? Which artists should be allowed to paint them, and which should not? How do power, economic violence, gender, culture and race play out in the streets of the RiNo Art District?

This particular battle started at the popular Crush Walls in September.

Denver artist Jolt, who was commissioned to paint this wall as part of the twelve-year-old festival, chose to take on gentrification in the neighborhood through a satirical political mural. That approach is rare in Denver’s street-art scene, which often favors bright, colorful photorealist portraits of animals, futurist geometric design and artful takes on old-school wild style – usually sanctioned by real-estate developers and city boosters. If graffiti is the language of powerless communities finding their voice and resisting dominant culture, permitted street art has too often become the trendy wallpaper decorating cultural domination.

Criticism like Jolt’s is an infrequent intervention.

Jolt’s mural in progress at Crush Walls 2020.

Kyle Harris

Jolt’s mural was a direct jab at three people he views as responsible for the destruction of the longstanding Black and Latino communities near Larimer Street. The wolf referenced powerhouse developer Ken Wolf, the force behind the Denver Central Market. The vulture was a slam at superstar street artist Pat Milbery, one of many white artists Jolt considers “culture vultures.” The painting depicted Milbery’s signature fashion and included a small image of his popular “Love This City” heart. Next to the vulture was a rhinoceros, the symbol of the RiNo Art District, which is often blamed for the gentrification of the area. The three characters were sitting around a table, and a cartoon bubble rose from the vulture: “So a rhino, a wolf & a vulture walk into a community…”

Weeks after Jolt’s mural went up, it was buffed over by a thin coat of white paint that barely concealed the piece beneath it. “Personally, it looks as if it was done in a hurry,” Jolt told Westword at the time. “Whoever did it spilled paint all over the ground.”

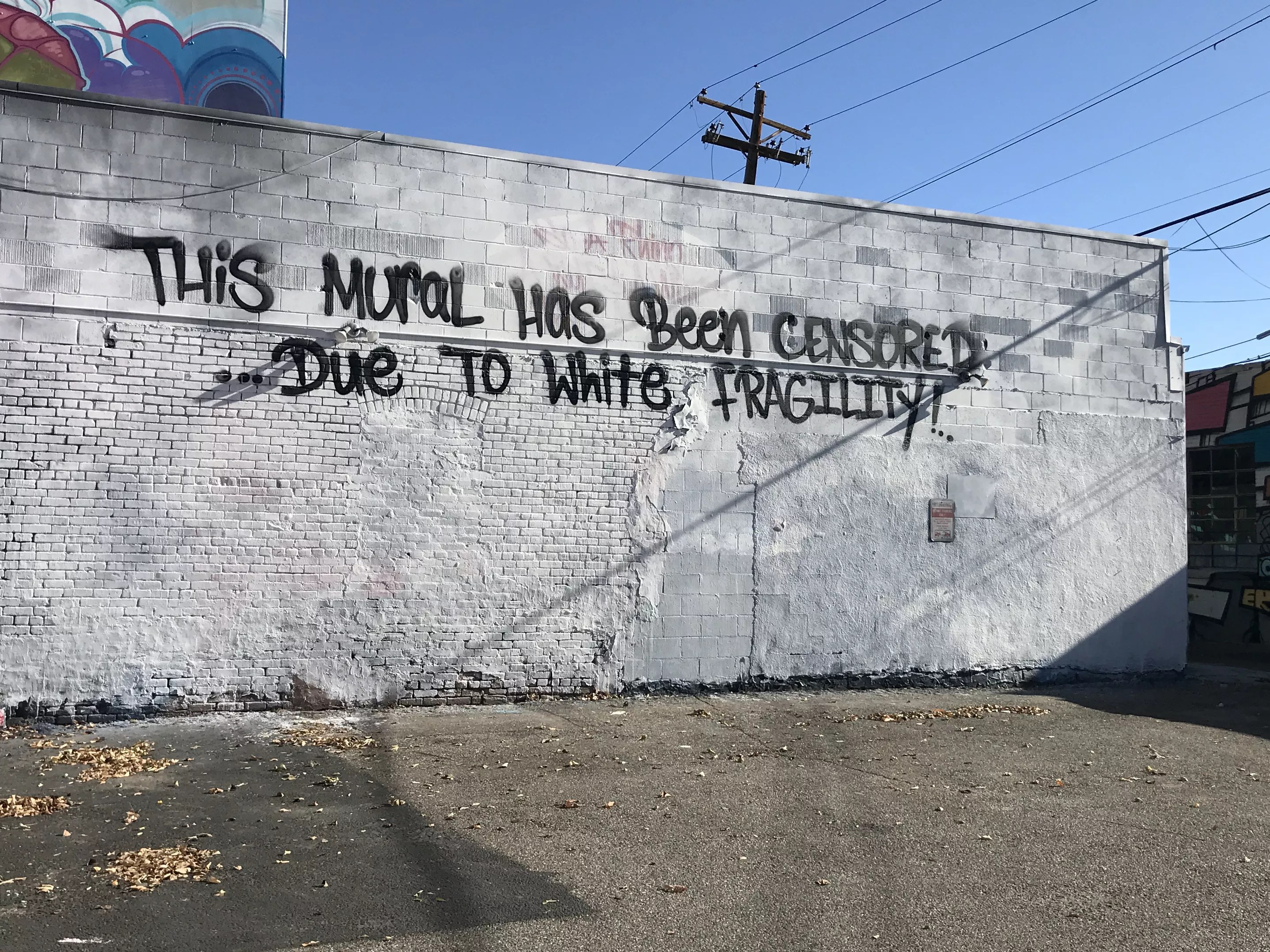

Jolt then added his own message to the buffed wall: “This mural has been censored…due to white fragility!”

Jolt’s Crush 2020 mural was painted over, and then this slogan appeared on the whitewashed wall of American Bonded.

Kyle Harris

In the weeks that followed, the wall became the focus of more graffiti and tags. One person sprayed the phrases “Racists gonna racist,” “Hate message” and “This artist is a racist and a bigot,” with arrows pointing toward the phrase about white fragility. That was soon covered by a larger, text-based piece of the word “CIGA.”

This drama was a sideshow to a disastrous year for Crush Walls. The pandemic had already shut down most of the festival’s public events. Then, just days after the festival ended, prominent artist Grow Love and others accused Crush Walls founder Robin Munro of sexual assault, claims he denies. That fueled a larger debate about sexism and sexual violence in the Denver art scene – adding to a discussion that had started months earlier, when then-Buffalo Exchange Colorado co-owner Patrick Todd Colletti was accused by dozens of women of rape, leading to his ouster and the closure of the local Buffalo Exchange shops.

At the start of December, Crush Walls and the RiNo Art District, which had partnered with the event a few years ago, parted ways. RiNo Art district founder and director Tracy Weil says that the organization will pursue other street-art projects. Munro, through his attorney, told Westword that he is building a new crew of artists who will keep Crush alive in RiNo and beyond.

Meanwhile, Breckenridge artist and social-justice activist Shannon Galpin decided it was high time for an art intervention celebrating women’s rights and claiming space from predatory men in the street-art scene. Galpin, whose work in Afghanistan has garnered her international praise, says she wanted to show up for artists who were survivors of rape and sexual assault, and celebrate their work.

So Galpin teamed up with Koko Bayer, the artist behind the city’s series of wheat-pasted hearts with the words “hope” and “esperanza” inside, who has deep roots in Denver (her grandfather was famous sculptor Herbert Bayer). They connected with the RiNo Art District and RedLine Contemporary Art Center about securing a wall for a project celebrating women and non-binary street artists. The American Bonded wall, where Jolt’s mural had been buffed and then turned into an eyesore by taggers, was available, and so Galpin and Bayer planned to create one of Galpin’s love letters on the spot.

“Yes, the white fragility statement was powerful because it spoke to the censorship,” says Galpin. “If that was all that was on the wall, I would have felt very differently about it. It had twenty other people making other comments on it. Everything was around hate.”

Two days before Galpin and Bayer started work, the CIGA piece appeared. “We were pasting over CIGA. It wasn’t just ‘white fragility.’ That was already buffed out,” Galpin notes.

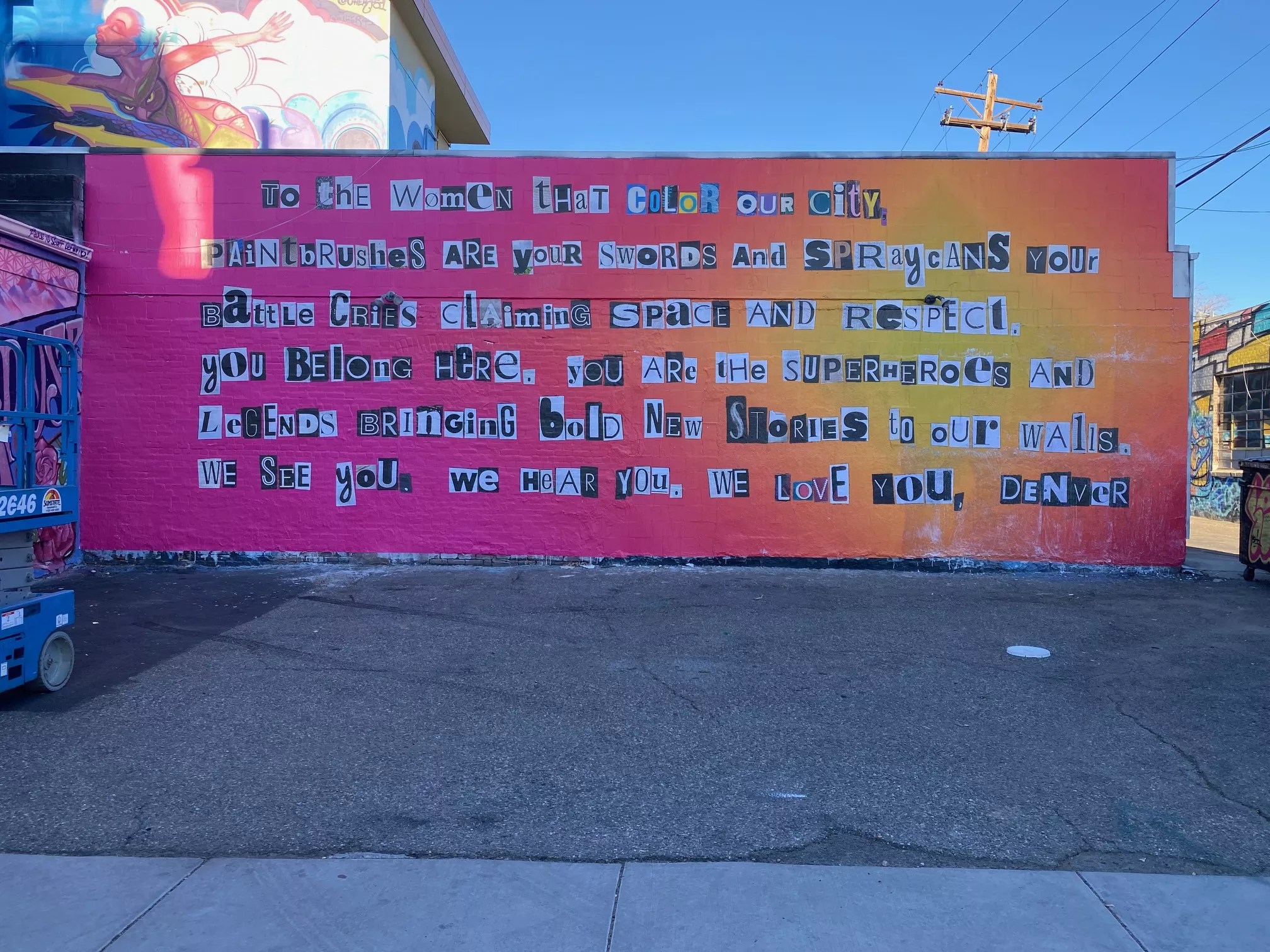

Shannon Galpin and Koko Bayer’s mural celebrates women in the street-art scene.

Shannon Galpin

Galpin and Bayer’s piece, which went up the same day that Westword reported the RiNo Art District/Crush Walls split, had this message: “To the women that color our city, paintbrushes are your swords and spraycans your battle cries claiming space and respect. You belong here. You are the superheroes and legends bringing bold new stories to our walls. We see you. We hear you. We love you, Denver. “

This was an upbeat declaration, written by Galpin, for women artists to fight the patriarchy, set on top of a colorful background painted by Bayer, and the latest salvo in a long struggle for broader representation of women and non-binary people in the street-art scene. One of the leaders in that fight has been Alexandrea Pangburn, who moved to Golden in 2017 and has worked tirelessly with the RiNo Art District and Crush Walls to successfully increase the representation of women and non-binary artists in the festival; she also co-founded the competing women and non-binary mural festival Babe Walls, which took place in Westminster over the summer. Pangburn’s efforts highlighted a culturally diverse crew of artists and styles, unified by their gender identity.

But many of the women and non-binary artists criticizing the city’s longstanding street-art scene are white and from other cities, people moving to Denver from the very demographic that has obliterated so many longstanding communities of color. In the city’s street-art movement, which has roots in hip-hop graffiti and Chicano muralism, Jolt is not alone in arguing that too many white transplants of all genders are asserting themselves as curators and artists, and that they lack respect for the culture and people who have been doing this work for decades. Novices shouldn’t be given walls without earning them, Jolt says, and nobody should be painting over the history of the city and colorizing gentrification while appropriating the art forms of the very communities being displaced.

Galpin, who has been at odds with Jolt since he told her that her work does not belong on the city’s walls because she does not understand the culture in which he grew up, says she appreciates his satirical artwork and criticisms of gentrification, but doesn’t like what she describes as his “bullying” – a characterization he dismisses.

“I truly wanted to support the women who are dealing with issues brought about by bad men,” Jolt says. “I’m a father of an amazing young lady, so from that perspective, street art aside, I’m understanding. However, the disrespect and dishonesty expressed toward me has made me not want to even utilize my voice anymore to help.”

Jolt doesn’t think much of Galpin’s new work. “The irony of the message she put on the wall about ‘claiming space’ sounds like colonization,” he says.

But it’s necessary for women to claim space, argues Galpin – especially in the street-art world, where they are often under attack by men in power.

“When we have shared our stories of bullying and abuse, we are ignored,” says Galpin. “We are laughed at. We are diminished. That has been going on for years. This isn’t that year. This is about the fact that we created something positive to celebrate the women who have been ignored and simply want to be part of bringing beauty to our streets.”

According to Jolt, however, women have always been celebrated in the street-art scene, even if it has been largely male-dominated.

“There have always been women in the graffiti/street art world, and they were never victimized or divided from the obvious predominantly male-driven culture,” he says. “If anything, they have always been respected more so for that fact. I’ve witnessed many people play the culture from the sidelines and inject themselves into a place of curative control. That seems to be par for the course with white folks and most street cultures…and holds true for Crush and its founders.”

Shannon Galpin and Koko Bayer’s mural on the side of American Bonded, vandalized.

Shannon Galpin

Bayer and Galpin took three days to put up the mural, and the night it was complete another artist tagged it with a menacing cartoon character. They repaired it, and it was covered again, this time with ugly swirls of white paint.

“You guys can tag it all you want,” says Galpin, who does not believe Jolt was responsible for the destruction. “But it’s only going to make the message louder.”

Jolt, who graduated from North High School, is biracial and says he’s speaking on these issues from the perspective of a half-white man, blames Galpin and other white artists for sowing discord. “Before all these white folks discovered my culture a few years back, there wasn’t any of the toxic energy in the scene,” he says. “They’ve hijacked the struggle and silenced the voices of the oppressed while bringing a lot of Eurocentric toxicity and, dare I say, even toxic femininity to our art form. I miss the days when the art and community would speak for itself. By nature, women in our street culture were very strong and didn’t victimize themselves nor create a separation like I’m witnessing with this group.”

Galpin insists that her vision is one of love, community and hard conversations. She wants to bring people together, and hopes to lend a hand in the fight against predatory development.

“You can find progress and can build community, if you’re willing to actually do the work,” she says. “But, man, that work is hard and messy. I am trying to create murals based on what I know. I’m not trying to be the ambassador for gentrification. I’m trying to be the ally. … I think we need to having reconciliation trials like in Rwanda and South Africa. You need to bring the most polarized people together to share. But all parties need to be willing to do that from a position of growth and community – not a position of a pissing contest. That’s why I hope that Koko’s and my approach to this is building community. It is about: There’s more power in love. Koko said it really well: ‘This is like the John and Yoko approach.'”

At least Jolt and Galpin can agree on one thing: Crush Walls.

“There is a whole movement #BoycottCrush,” Galpin says, and it’s a movement she supports. “No other artist should take that job.”

“In terms of Crush and beyond,” adds Jolt, “I think the chickens have come home to roost, so to speak.

“The one thing that is fact and can’t be ignored is that all of these people are Anglos that discovered a culture that I grew up in, and [they] brought absolute toxicity into it,” he says. “A level of gross hate that never existed prior. The gentrification of the literal landscape and colonization of the culture is sad to see.”