“It is an exploration of how art can be a form of agency, how art can be a way of taking up space as a woman in a patriarchy, and how these artists, through their art, inscribed themselves into our present,” says Dr. Einor K. Cervone, associate curator of Asian art at the DAM and co-curator of this exhibition, which runs from Sunday, November 13, through May 13, 2023.

Showcasing more than 100 artworks from roughly thirty artists, Her Brush immerses visitors in various realms of early-modern to modern Japan while taking a comprehensive look at the social circumstances that inflicted the limitations, obstacles and hardships the artists faced.

Ōtagaki Rengetsu, 太田垣蓮月, Travel Journal to Arashiyama (Arashiyama hana no ki), 1791–1875. Album; ink and color on paper.

Denver Art Museum: Gift of Drs. John Fong and Colin Johnstone, 2021.206. Photo © Denver Art Museum

Cervone reflects: “We are undermining these concepts, but we’re also showing that it was a tremendous journey for them to become artists. It was difficult in Japan, it was difficult in the U.S., it is difficult today.” The intentional contrast initiates viewers into the stories of the women artists, who navigated the different realms of society in order to leave their mark.

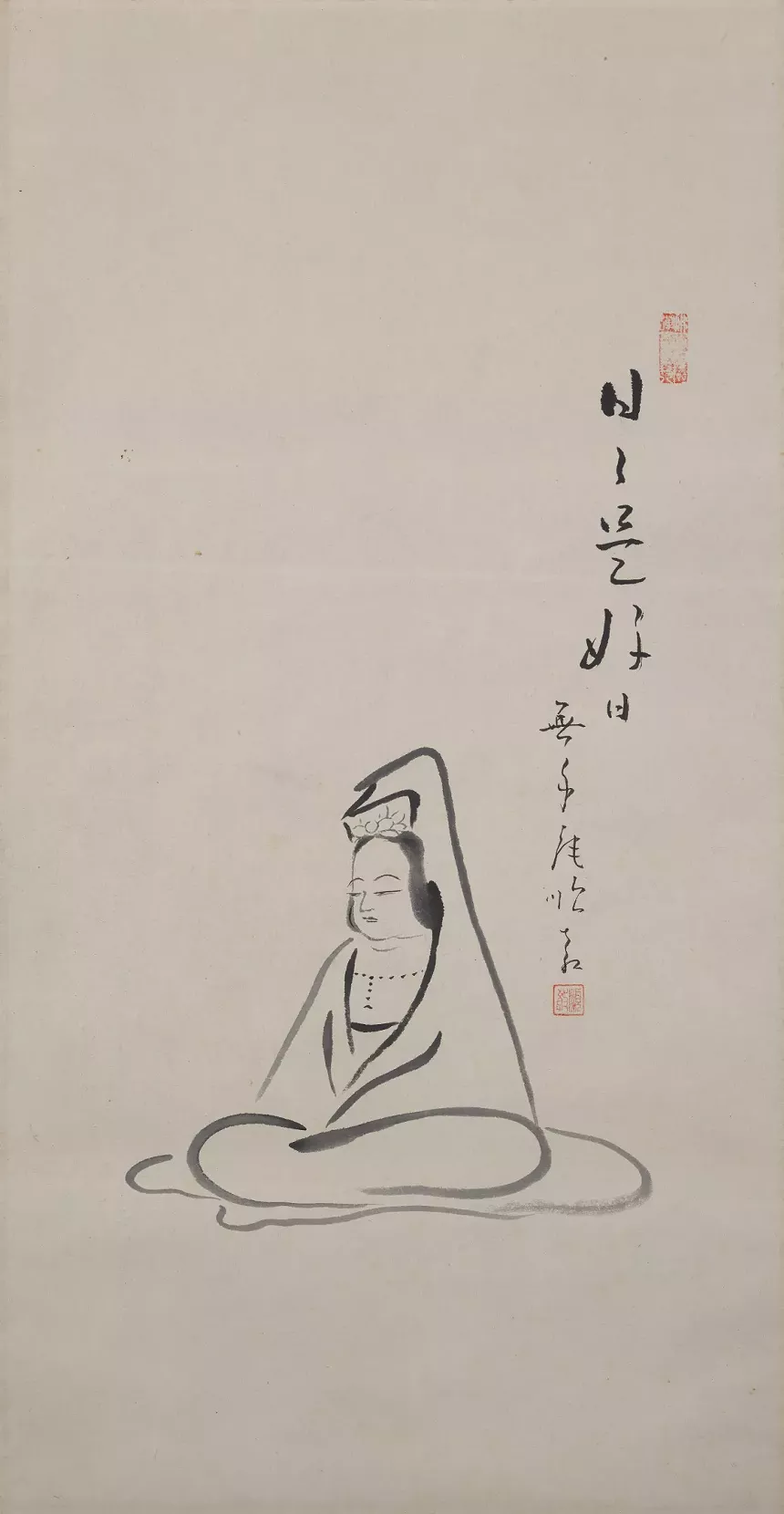

Ōishi Junkyō 大石順教, Kannon (Avalokitesvara), mid-1900s. Hanging scroll; ink on paper.

Denver Art Museum: Gift of Drs. John Fong and Colin Johnstone, 2018.156. Photo © Denver Art Museum

These realms are illustrated through the themed rooms in the show, such as the "Inner Chambers," which illustrates how women born into aristocracy were trained in the "three perfections" (poetry, painting and calligraphy). But these women utilized their education to become artists, transcending their subordinate place in society. “Learning to paint and write poetry and calligraphy [in Japan] was a bit like learning how to play the piano in Victorian England," Cervone explains. "You were educated to play in the parlor and entertain, to be a proper lady. But becoming a pianist — that’s a different story. That’s what these women did.”

Another realm displayed is called "Taking the Tonsure," which tells the stories of women who became Buddhist nuns in order to gain more personal freedom to pursue their art. “The Edo period was very restrictive in terms of movement,” Cervone says. “It was very hierarchically dictated who could travel and where, and women were not allowed to travel without male companions. Becoming a nun was a way to circumvent that.

“However, this was not the easy way out,” Cervone continues. “Some of the stories are quite triggering. One of the artists was so beautiful that she was turned away from the temples where she wanted to become a disciple because her beauty would have distracted the male disciples. So she took a searing iron to her face and she defaced herself, and so she proved her incredible tenacity and dedication to the faith.”

This is just one of many moments throughout the exhibit where visitors can appreciate the extreme fortitude that each of the artists represents. As they experience the interweaving realms in which women found their way toward self-expression, such as the familial "Daughters of The Ateliers," the academic "Literati Circles" or the entertainment milieu of "Floating Worlds," they are immersed in the feelings, the stories, the artwork and the complex nature of what it meant to create a legacy as a woman of this time.

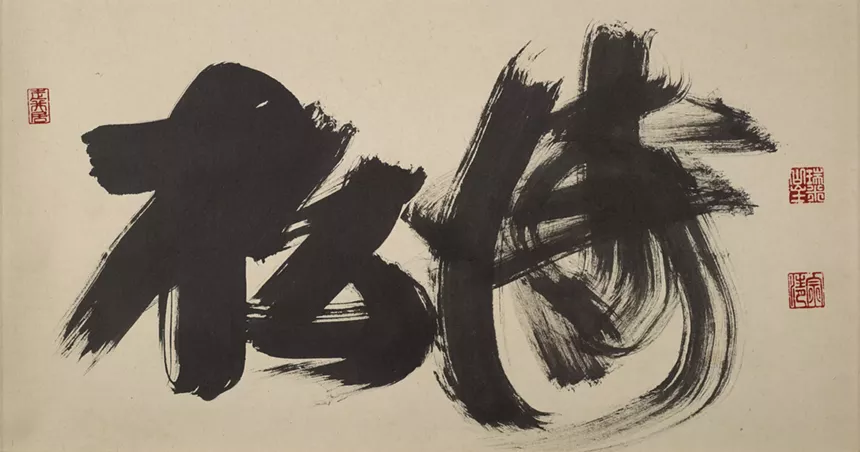

Murase Myōdō 村瀬明道, Breaking Waves in the Pines (Shōtō), late 1900s. Hanging scroll; ink on paper.

Denver Art Museum: Gift of Drs. John Fong and Colin Johnstone, 2018.155. Photo © Denver Art Museum

“Some of these artists are practically unknown in the U.S., and very little known in Japan,” she continues. “Not because they weren’t famous in their own time, but because of art institutions’ preferences and the circumstances of our own time. This is something that, as a society, we need to be self-reflective of, and reconsider what are the decisions that we’re making in terms of creating narratives for art history.”

Her Brush calls attention to these nuanced issues both in history and the present, and also incorporates contemporary artwork by local artist Sarah Fukami in the form of poetry slips (tanzaku) that visitors can collect throughout the exhibit and take home with them. It also includes contemporary calligraphy throughout the wall text by Kawao Tomoko, a Kyoto-based painter and performance artist.

One of the most exciting events to look forward to will be in March 2023, when Kawao will come to the DAM as a visiting artist for two weeks to work with a community of women who have gone through immigration. She will be sponsored by Denver’s Studio SML | k, and her time will conclude on March 21, 2023, with a live performance in the Morgridge Creative Hub in the new Martin Building.

Her Brush also involves an interactive projection screen, inviting guests to physically experience leaving their mark on the last wall of the exhibit. “Imagine the tenacity of taking ink and brush and leaving your mark on a piece of silk, and knowing that this will remain” says Cervone, “This is a way to inscribe yourself into our presence. It’s a remarkable, gutsy act of taking up space as a woman. ... This notion of leaving a brush stroke is a way of deciding that your artistic voice is important enough to be heard.”

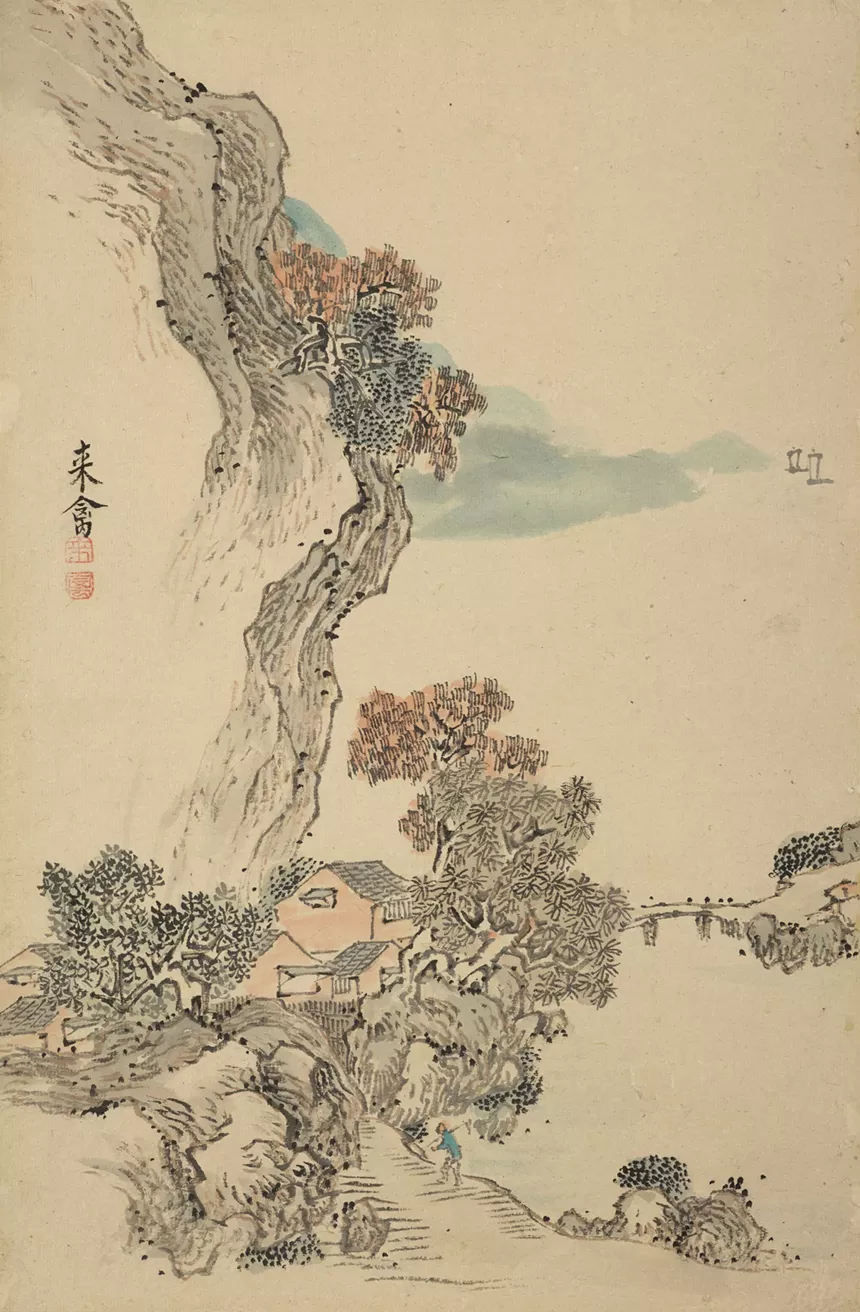

Kō (Ōshima) Raikin 高(大島)来禽, Autumn Landscape, late 1700s. Hanging scroll; ink on paper.

Denver Art Museum: Gift of Drs. John Fong and Colin Johnstone, 2018.193. Photo © Denver Art Museum

Her Brush: Japanese Women Artists from the Fong-Johnstone Collection, Denver Art Museum, 100 West 14th Avenue Parkway, Sunday, November 13, through May 13, 2023. For tickets and more information, visit the Denver Art Museum website.