Wes Magyar

Audio By Carbonatix

If you had told me five years ago that part of my art practice would include breeding snails, I would have looked at you like you’d sprouted your very own eyestalks on top of your head. But when you follow a muse, she leads you down crazy paths…and you never know what will kick off the journey.

In the case of my giant snail drawing in the Arvada Center’s current Paper.Works show, that journey started on a biodynamic farm in the Catskill Mountains called the Straight Out of the Ground Farm, run by an amazing woman named Madalyn Warren. I’d been selected to spend time there as part of the Andes Sprouts Society residency, which she also ran. Initially, I went there to work on a project with fireflies, but I had the wrong technology with me for an area so far from the city, and my sparse programming skills and lack of preparation didn’t help. One afternoon, sitting on the porch and picking snails off of the tiny garden in front of it, I put a snail on the black cover of my sketchbook and was transfixed as a gossamer, iridescent thread stretched behind the snail’s gooey body. Who knew snail slime was so beautiful? It glistened and created rainbows in the sun, even when dry.

The very first snail drawing done in the Catskills.

Lauri Lynnxe Murphy

When I returned to Denver, I couldn’t get the mark that snails left out of my head. I had previously been collaborating with bees to make artworks, but an allergy to their stings had left me without a natural collaborator. Snails seemed a good alternative, but where would I get snails in the high, dry desert of Colorado?

Thinking that everything could be shipped, I began my hunt. But it turns out, snails are illegal to ship, since they are an invasive species. Complaining on Facebook led me to a friend who had five pet snails in a tank, taken from someone’s garden. As her daughter had largely lost interest, I took possession of a small tank with purple sand and got a crash course in caring for snails. In the heat of the summer, they simply adhered themselves to the glass and hibernated, a thin membrane of hardened slime keeping in some moisture. I sprayed them constantly, but still lost a couple to age…and three snails weren’t enough to do a drawing with. And any breeding attempts to create more proved less than successful.

Leading the way.

Lauri Lynnxe Murphy

I still managed to start working with them, slowly…trying to figure out how to preserve their trails through sprays and coatings, but each attempt failed to preserve the luminescent shine of their slime. In fact, I found that most attempts at preservation simply caused the trails to disappear. Even handling the paper would cause the delicate layer of snail slime to flake away and vanish.

At a certain point, I realized that the best way to preserve the contours of their travels was to cut away everything around the trails…which left me partially erasing it with the movement of my hand. But the poesis of this felt like a metaphor to me: When can we touch anything in nature without creating a human footprint? How do we preserve things without also erasing what they are? How could I make the invisible visible?

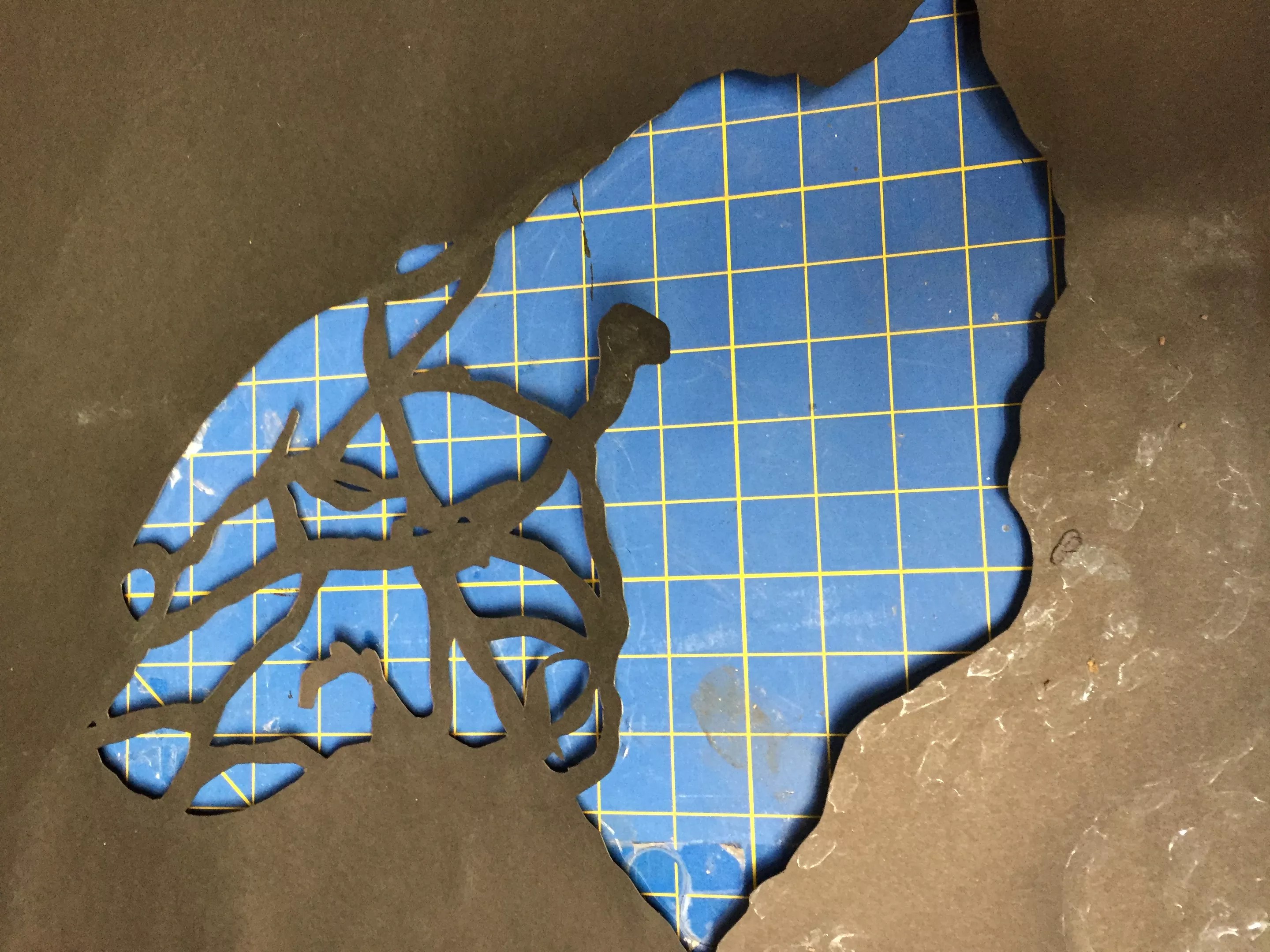

The cutting mat.

Lauri Lynnxe Murphy

As I worked on these “drawings,” painstakingly cutting the matte areas away around the shiny dried snail slime, I kept feeling that I needed to go larger…but paper is sold in pre-set sizes. Then Collin Parson asked me to create a site-specific work for the Arvada Center’s paper show. He showed me the problematic curved wall at the entrance to the space, always a challenge for the staff to install work on, and asked if I thought I could make something to fill that 26-foot-long wall. I said “yes” before I thought through how to do it, excited for the opportunity. All I really knew was that I needed to get a big roll of paper…but could I find bigger snails?

Each snail in this process makes a different line, mostly according to its size. The average size of my “paintbrushes” ranges from quarter-inch-long babies (they don’t leave much of a line at that size) to one-inch-long adults. The perfect partner for this task would have been the Giant African Land Snail. Coming in at about seven inches, its trail would have made a magnificent mark much thicker than the lines I had been cutting out.

However, Giant African Land Snails are considered an invasive species, and for good reason: Needing a steady supply of calcium to feed growth of their shells, they have a habit of eating stucco off of buildings and also devastating agricultural crops. So in the areas where they have begun to appear in the United States, usually sneaking in via shipments from far-off lands, they are rounded up and destroyed – Florida kills around 200,000 a year. Needless to say, shipping any to Colorado would be illegal.

So I started calling university entomology departments, in a desperate search to find some I could maybe “borrow” by traveling to wherever they were. Even that didn’t yield much, and the clock was ticking:

With only a few months to complete this mammoth project, I needed either a lot more snails or bigger ones…what else could work?

My helpers get to work.

Lauri Lynnxe Murphy

If nothing else, I needed to increase the number of snails I had, but so far, most breeding efforts had ended in the snails eating their own eggs: I’d only managed to create a crew of twenty snails, divided between two ten-gallon tanks. I wondered if more space might help.

A few days of diligent Craigslist searching rewarded me with a 55-gallon former python home. After I’d layered some dirt and moss inside and created a habitat, on the very first day I knew it was the right choice. Snails have a lot of sex and go at it for twelve hours or so…. My new habitat was a 24/7 gastropod bordello. Within a week, clutches of shiny white eggs began to appear underneath the dirt, and within a month, 150 tiny snails dotted the glass. But they weren’t going to grow fast enough for this project, I feared.

New baby snails hatching!

Lauri Lynnxe Murphy

Google turned up an option I hadn’t considered: banana slugs, which are six inches long at adulthood and plentiful in the Pacific Northwest. I found a scientific supply house that sold them – but it didn’t have any in stock, and it would be spring before its slug-hunters could replenish the supply. I checked back weekly, anxiously, until the supply house could finally ship me four banana slugs.

Banana slugs!

Lauri Lynnxe Murphy

Finally, FedEx delivered a box with a plastic container filled with four listless slugs on an ice-pack, who got a little more lively after they rehydrated and acclimated to their new environment. However, all this waiting yielded nothing but disappointment – not only did the slugs’ sticky slime fail to adhere to the paper, but boringly, they only went in a straight line! It’s ordinarily hard to see the slime trail when I’m working, but the slugs merely dampened the paper, making it almost impossible to see. I would just have to work with the twenty original snails.

Snails and slugs together.

Lauri Lynnxe Murphy

It was time to get to work. With two 4′ x 8′ tables placed side by side, I could accommodate the eight-foot width of the roll of black paper, but the majority of it needed to stay rolled as I worked in eight-foot sections. This meant I would not see the completed piece until it was unrolled and put on the wall at the Arvada Center. Placing the snails on the table, I was able to cover six feet with their curious ramblings each evening. My rules were simple: I was only allowed to move them when they’d reached an edge, though it was important to plan their placement carefully to connect with the previous work.

The piece emerges.

Lauri Lynnxe Murphy

The snails, of course, were the fast part of this process: The rest was laborious and careful, requiring patient cutting with an Xacto blade around the contours of their squishy trails. So every day, I would place a large cutting mat under a section, bend back-breakingly over the table, and cut. And cut. And cut. Hours would pass unnoticed, as I entered a flow state and meditated on the disappearing trails…and the disappearing nature in our world. Every day, my goal was to roll at least two feet of a section, carefully pulling the paper taut and winding it up, exposing more terrain for the snails to explore.

Cutting, cutting, cutting.

Lauri Lynnxe Murphy

After months of this careful and painstaking work, I still couldn’t imagine what it would look like on the wall. Arvada Center master installer (and my longtime friend) Dave Seiler had visited the studio to devise a strategy with me, and painted dozens of tiny nimodium magnets flat black. When I arrived at the gallery with my long roll of paper, it took four of us to carefully unwind it across the curved wall and secure it with nails at the top.

I confess: Seeing it unrolled was incredibly moving. I was surprised at the variation of lines from different sessions, even though I had attempted to be as methodical as possible. From that point, I simply finessed the push and pull from the wall to make sure it was stable and to maximize the impact of the shadows cast by the work. We embedded nails in the wall, then used the tiny magnets to hold the paper in place.

All hands on deck!

Lauri Lynnxe Murphy

You might think that I’d be done with snails after all those hours of snail-watching and 24 feet of painstaking cutting. But if anything, seeing the possibilities of large-scale work with such tiny creatures has only spurred me on, and I’m still putting my friends on black paper and tracing the contours of their journeys with the sharp point of my knife.

Now all of those babies are teenagers, making their own graceful, sticky paths. They seem as excited to explore as I am.

See Paper.Works at the Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities, 6901 Wadsworth Boulevard in Arvada, through Sunday, August 20. The gallery is open from 9 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. Monday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. Saturday, and 1 to 5 p.m. Sunday. Find out more at arvadacenter.org.