Audio By Carbonatix

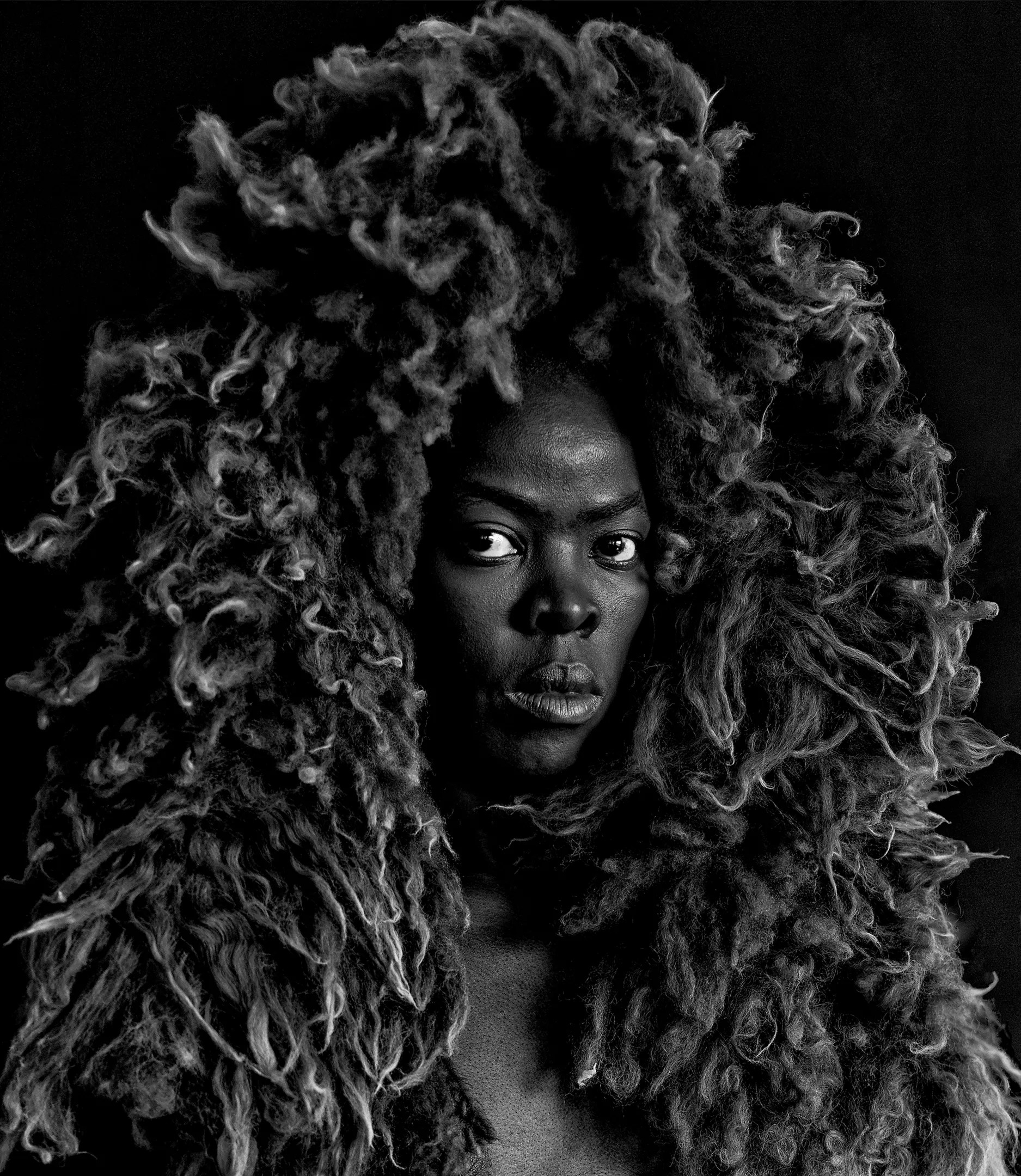

Walk into the Center for Visual Art MSU Denver, and you’ll find photographic imagery staring back at you in a stark black-and-white message of politics and the personal. The exhibition, Somnyama Ngonyama/Hail the Dark Lioness, which opened last week, is a visual tour de force of more than eighty self-portraits from the queer South African artist Zanele Muholi (they/them), who advocates equality for South Africa’s Black LGBTQIA community through powerful imagery.

The first image you’ll see, says CVA director Cecily Cullen, is “Julile I, Parktown, Johannesburg.” It’s a “ten-foot-long, six-foot-tall image of the artist lying nude on the floor. At first glance, Muholi seems to be lying among luxurious pillows in a newspaper library. Then you see that it’s really a thin blanket with blown-up plastic bags.”

The startling image is made even more dramatic, Cullen adds, by the deliberately enhanced blackness of the artist’s skin set against sharp, high-contrast black-and-white textures and props.

“Muholi’s eyes are prominent and confront you head-on,” Cullen continues. “The work is hanging so the eyes are just above an average person’s height, creating a confrontational experience that’s also compelling and engaging. It also expresses a sense of vulnerability or trepidation in the way the figure grasps the pillows. One gets a sense of finding comfort from something upsetting in those piles of newspaper and the writing about news and history they carry.”

Mulholi, who’s been turning the camera on fellow artists in South Africa’s Black lesbian and trans communities for years, is easy to put in a box as a standard self-portraitist, but the artist eschews that label, and so does the new work itself. “Their preferred declarative is ‘visual activist,’ as opposed to ‘artist’ or ‘photographer,’ Cullen notes. By their own admission, Mulholi is striving, fists out and ready to fight, to reclaim blackness as it is co-opted by white assumptions.

“My reality is that I do not mimic being Black; it is my skin, and the experience of being Black is deeply entrenched in me. Just like our ancestors, we live as Black people 365 days a year, and we should speak without fear,” Mulholi says in an exhibition statement. That firm resolve is what sets the body of work in Hail the Dark Lioness apart from the general arena of performance-oriented self-portraiture.

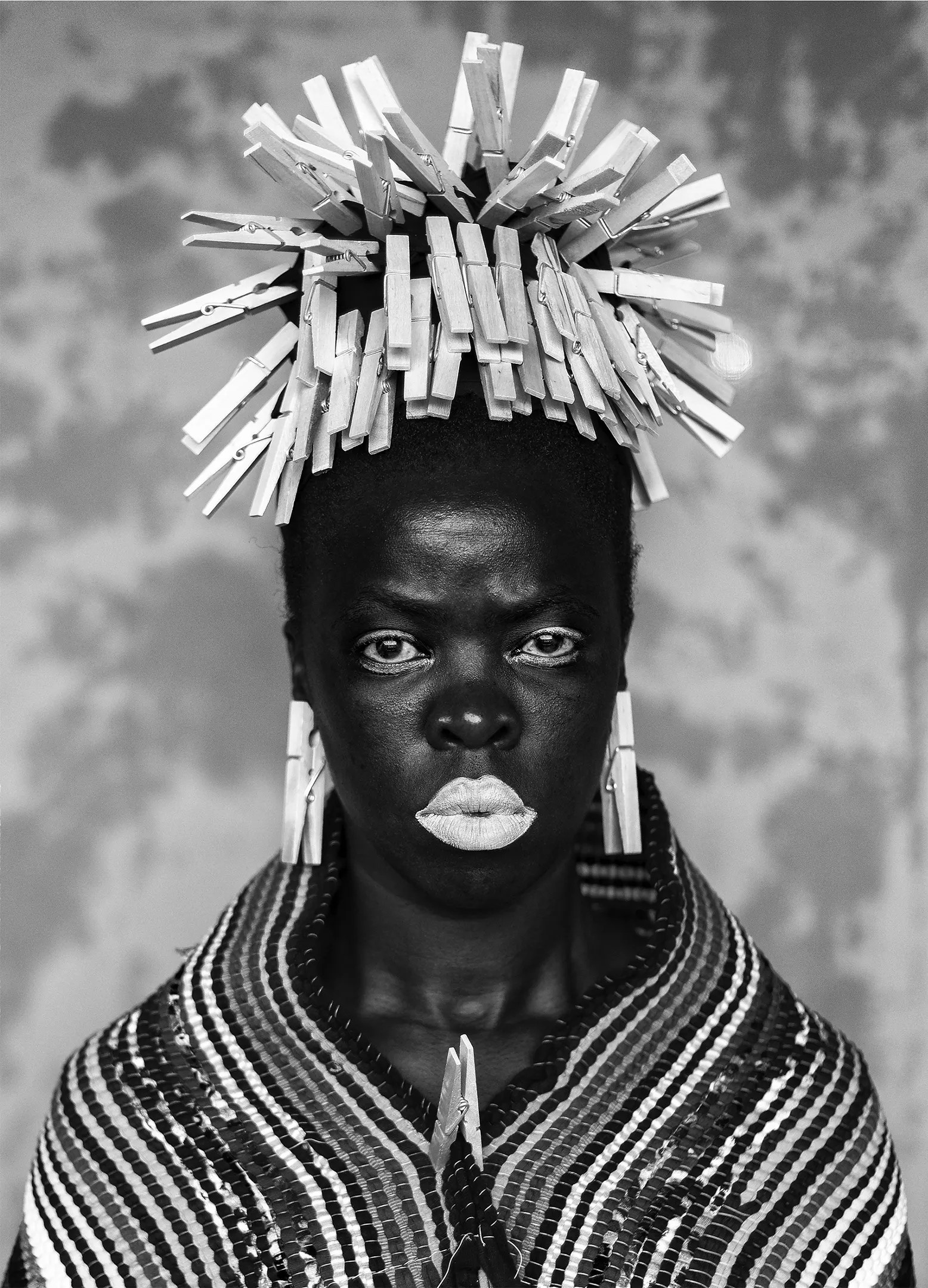

“By taking on many personas, Muholi is exploring stereotypical roles,” Cullen says. “Sometimes an image looks like tribal portrayal, but instead, if you look close up, you see that a headdress is actually comprised of looped bicycle inner tubes.”

Through the use of common and found materials, Mulholi throws the self-images into a grander arena as a demand for entry by disenfranchised minority groups into the canon of modern art.

“It’s fascinating to see so many photos of the same person,” she notes. “Muholi uses found objects to transform that persona, but it’s done so expertly: One image looks like the artist is wearing a nurse’s cap, but when you look closer, you see it’s a toiletry bag.

“Muholi also focuses a lot on tropes about beauty,” Cullen explains. “Seeing this image of a very dark African person as a beauty object, positioning themself in the realm of beauty, is expansive and also very natural: The wigs and tiaras have a tongue-in-cheek quality. There’s definitely a sense of humor in the work – but unexpected. It takes you by surprise.”

There’s a sense of “vulnerability, power and strength,” adds Cullen, pointing out how Mulholi stares down the violence faced by the queer Black community in South Africa.

Cullen also stresses how some materials – clothespins, for instance – “refer to stereotypical gender norms, like using the clothespins to indicate a domestic worker.

“Wigs and hair are important aspects to Black identity,” Cullen adds. “There are several images that work with the idea of hair and the use of crowns, headdresses or tiaras. One uses giant safety pins to form a crown and a draping necklace. Another has chopsticks porcupining out of a big pile of hair. Some refer to stereotypical gender norms, like the use of clothespins in one image, indicating a domestic worker.”

Scissors, power lines and scouring pads are just a few more of the loaded materials used to convey stereotypical confinements.

Cullen describes how, while hanging the show, she and her fascinated staff debated over which image they’d most like to take home: “It’s difficult to choose, because so many take your breath away. Some are wallpaper-sized and confront the viewer in larger-than-life dimensions,” she says. “Several are so striking, like the image on the announcement card, where Muholi has clothespins creating a crown-like form on their head and white paint on their lips and eyes, transforming the subject’s appearance. Some you can tell that it’s the same person, sometimes not.”

Zanele Muholi’s Somnyama Ngonyama/Hail the Dark Lioness runs through March 20 at the Center for Visual Art Metropolitan State University of Denver, 965 Santa Fe Drive. Guests wearing masks are welcome to visit the CVA from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tuesday through Friday, and noon to five Saturday. No more than twenty people will be allowed in the galleries at one time; additional COVID safety measures are listed in the CVA website’s FAQ. Learn more about the exhibition online.