Claire Duncombe

Audio By Carbonatix

An 1865 square grand piano that has seen its share of Colorado history sits in a living room in Commerce City. The elegant instrument rests on quiet carpeted floors amid a small collection of antique furniture. Homeowner Rochelle Ulrich, a CT-scan tech at Children’s Hospital, says the instrument, which has been a fixture in her family’s homes for many decades, doesn’t get played regularly. More often, it bears the brunt of her sons’ wayward Nerf darts and wheels of their toy cars.

Ulrich and her father, Jeff Ball, are proud of the piano’s history. Its most notorious chapter, they say, was a period during the 1890s when the instrument adorned the living quarters of mining tycoon Horace Tabor and his wife Baby Doe at the Windsor Hotel. The multimillionaire couple, whose lives have been memorialized in opera and film, were infamous for their wealth, extravagant lifestyle, scandal-clad love story and tragic end.

Ulrich and Ball believe the piano holds an imprint of the Tabors’ story within the intricacy of its design and distinctive resonance.

“The piano has a wonderfully warm and soothing sound,” Ball notes. “There’s a color. There’s a patina.”

The unique sound has developed subtly over time, like varnish edging its way onto bronze bowls. Rather than diminish the quality, the instrument’s age has enhanced the tone. The past lives on whenever hands find their way to the keys, and Ball and Ulrich do what they can to preserve the piano and its memories.

“For me, there’s a sense of privilege to be the steward of something,” Ball says. “There’s a certain passion involved – about not only history, but how you relate to it to day, in the present moment.”

Elizabeth “Baby Doe” Tabor.

Denver Public Library Western History Department

In Colorado, the Tabors’ story is the stuff of legend, and Ball recalls Caroline Bancroft, author of the sensationalist 1950 novel Silver Queen: The Fabulous Story of Baby Doe Tabor, visiting his high school and telling the couple’s sordid tale of romance and tragedy.

Horace, one of the wealthiest men in Colorado, had made his money through grubstake claims, a speculative practice that led to shares in three of the best-producing mines in Leadville in the late 1870s; he secretly divorced his first wife, Augusta Tabor, around 1881 in order to marry Elizabeth McCourt, aka Baby Doe, a notorious flirt who had split with her first husband. The second marriage horrified socialites across the state.

“I think it really was a true love story, [while] society really thought she was just a gold digger,” Ulrich says. “People love a good scandal, even back in the day. And she couldn’t rise above it.”

While Denver society judged Horace for his actions, Baby Doe became known as “the money grubber, the home-wrecker who married the richest guy around,” says former Colorado state historian William Convery. The couple never found redemption in the eyes of high society.

Nonetheless, for years the Tabors thumbed their noses at detractors and flaunted their affection and wealth, Convery says. They indulged in diamond-studded diaper pins for their daughters and experimented with owning peacocks within the grounds of their block-long Capitol Hill mansion.

But in 1893, the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act pulled the rug out from under them. In accordance with the Act, the government had committed to purchasing silver from mines at a premium. But with the government no longer subsidizing the precious metal, the price plummeted. The Tabors went bankrupt overnight, and they weren’t the only ones.

“It was a disaster,” Convery says. “Businesses folded left and right. There were runs on the bank as people tried to pull their money.”

Mines closed. Miners were out of work. It took decades for Colorado to rebuild its economy.

“The story of the Tabors is the story of Colorado at the time,” Convery explains. “It was very much a boom-bust economy, and nowhere was that more apparent than in mining.”

So the Tabors lost their mansion, but Horace still had enough connections to get a position as postmaster. The family moved into the Windsor Hotel, where they lived in a large suite. Horace died of appendicitis in 1899.

At that point, Baby Doe and their daughters returned to Leadville to see if she could renew prospects at one of her husband’s mines. But she died impoverished, mentally ill, and frozen in an old mining shack in 1935.

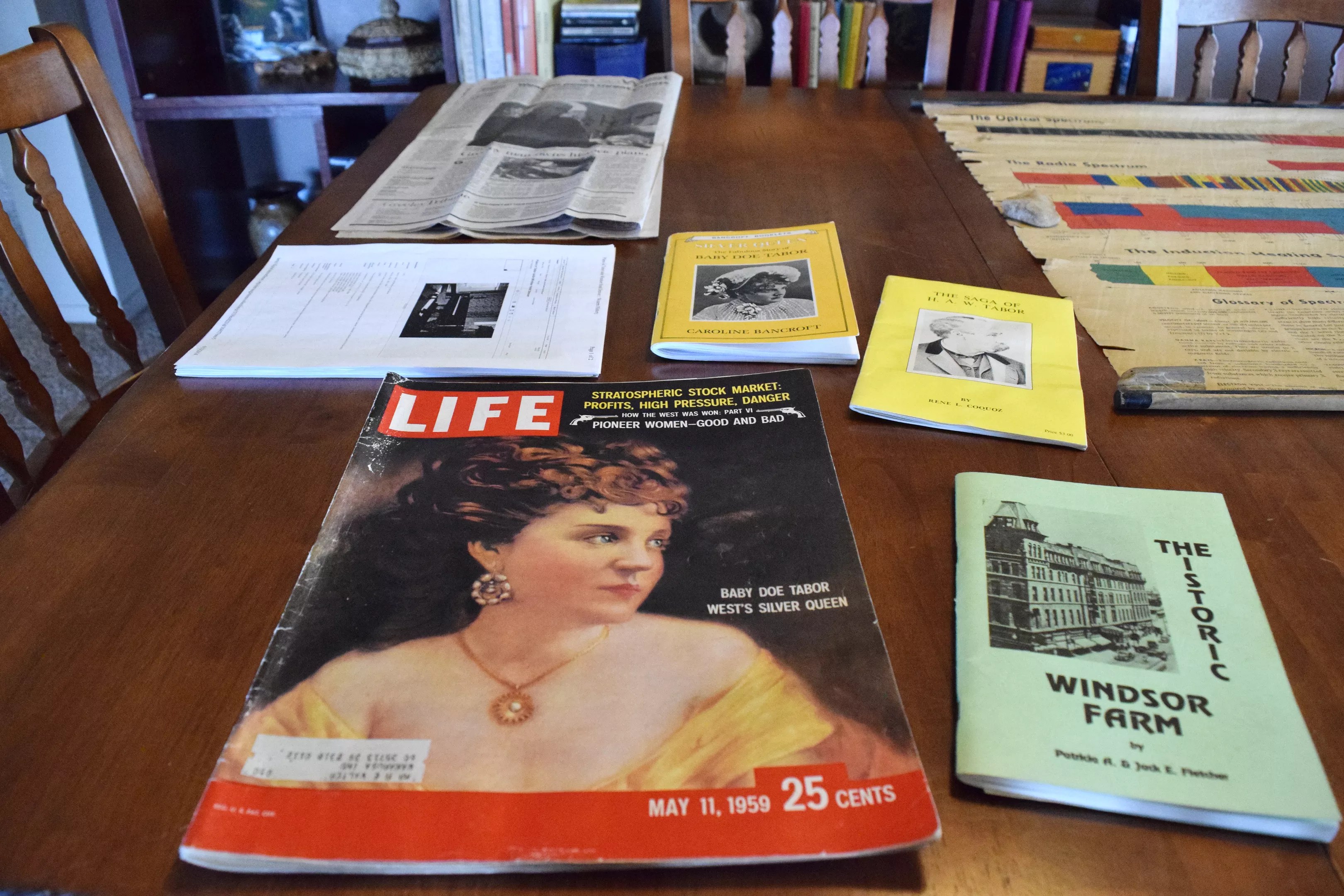

Baby Doe Tabor’s piano – which decorated the Tabors’ suite during the 1890s – first came into the Ball family’s possession during an auction at the Windsor Hotel just before it was torn down in 1959. Ball still has a clipping of the newspaper ad announcing the planned demolition, and he continues to lament the ruin of the historic building.

“The Windsor Hotel was the very finest in Denver when it opened [in 1880], about twelve years before the Brown Palace came into existence and eleven years before the Oxford Hotel,” explains Ball. “It’s reported that the hotel was constructed for a cost of $300,000, and the fine furnishings cost $200,000: diamond dust mirrors from France, walnut room furnishings with marble tops, et cetera.”

At the time, Ball was a teenager living in Sterling, a small town in northeastern Colorado. He believes his mom, Sandra Nelson Walters, and stepdad, Roy Johnson, went to the auction because of their love affair with the Brown Palace and the Windsor’s similar status as a historic landmark. When the couple returned to Sterling from Denver, they hired movers to tow the nine-by-four-foot piano along with two Tabor beds with marble-topped dressers back home.

Ball remembers the work the family put into restoring the piano after years of neglect. They stripped many coats of varnish from the instrument’s cabinetry by using chemicals to loosen the lacquer, and bread knives and other tools to scrape the finish away.

“I had the job of doing all the detail work on the legs, which are hand-carved and very ornate,” Ball recalls. “We’d piece away at it on a cold winter night, when it was easier to be inside.”

Underneath all the varnish, they uncovered the original Brazilian rosewood.

This particular piano was built at the Bradbury Piano Company in New York City in the early 1860s. Tom West, owner, tuner and technician of West Piano Service in Denver, estimates by its serial number that the piano was built in about 1865. Many antique pianos are recorded in the Pierce Piano Atlas, and the Bradbury Piano Company’s records are included. In 1860, the company had made 9,000 pianos, and by 1865, they listed 10,100. The Baby Doe Tabor piano was number 10,094.

Around the time the piano was constructed, 164 men worked for the company, and they were paid an average of $50 each month, according to Antique Piano Shop, a piano store in Tennessee that records histories of antique pianos.

The details of the piano’s construction fascinate Ball, who imagines the journey of the wood from Brazil to New York, as well as the conversations that occurred while the strings were strung and the hammers positioned.

“Can you imagine how many hands were on that instrument?” he muses.

How the piano spent its years in New York before moving across the country to be installed at the Windsor Hotel is a mystery, but “a piano like this most likely came out [to Denver] on the train from back east,” West says. It was then installed in room 302 at the Windsor Hotel sometime before the mid-1890s, when the Tabors moved in.

The piano once graced the hotel suite of the infamous silver baron Tabors. They lost all their wealth after the silver market crashed in 1893.

Claire Duncombe

There are no records of what the piano sounded like back then, but Ball loves how the instrument’s age creates unique variations in sound. The intonation can change depending on where fingers are placed on each key. He compares the piano with modern Steinways, whose every note is clean and sharp, “which is beautiful for playing Chopin in a music contest of some kind where you want that absolute sharpness. Gosh, [this] can be so much more expressive.”

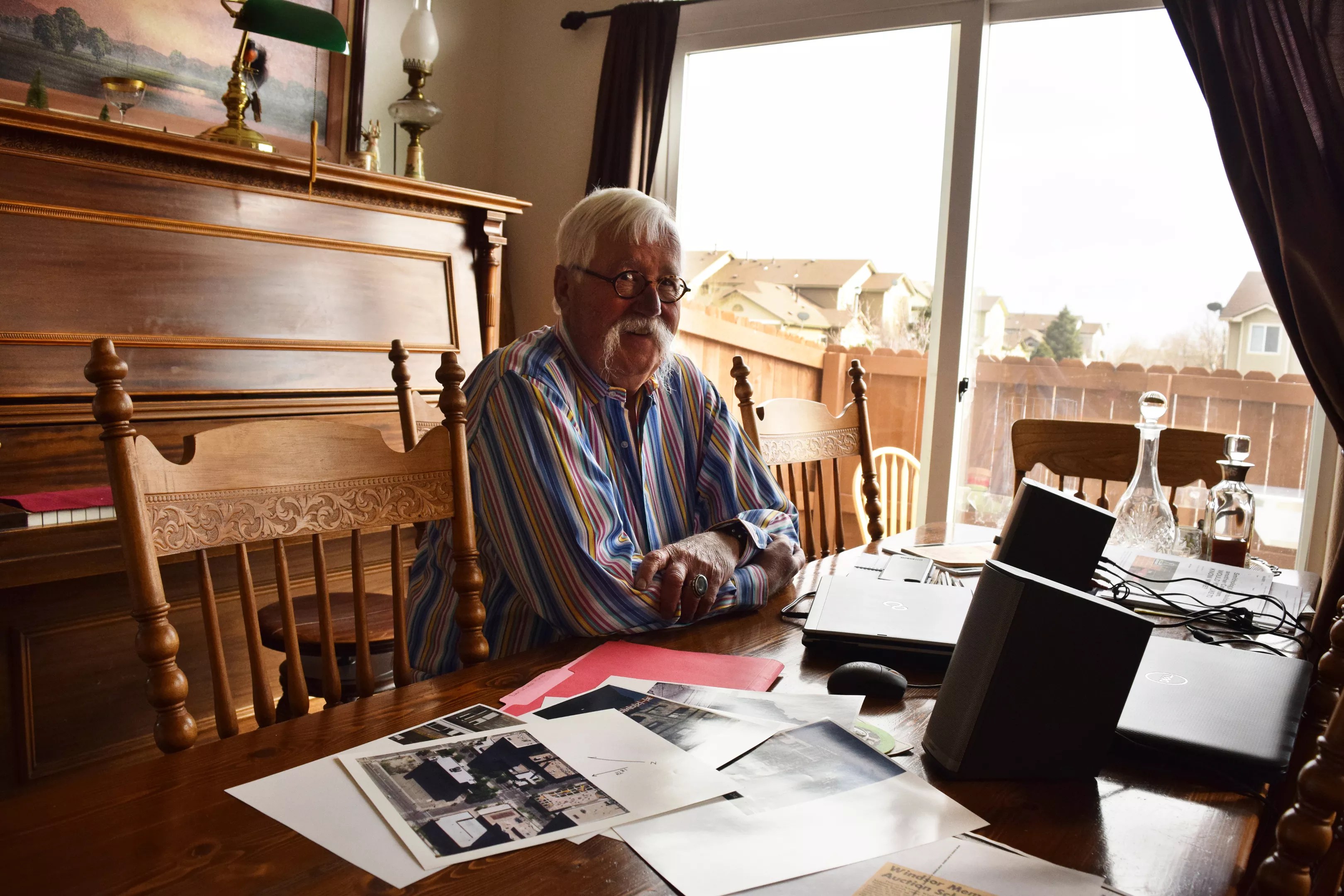

Ball, a 76-year-old lifelong romantic, recounts some of his early memories of listening to music with tears in his eyes. His parents were high school sweethearts, and he spent the first decade of his life living with them and his siblings in Phoenix, Arizona.

“They had a real simple little record player, a 45 RPM, very crude, but they had a stack of records,” he remembers. “It’d take a whole stack of records to get through one symphonic piece.”

When he was a kid, they listened to opera, and he was introduced to Bach’s Brandenburg concertos and Mozart.

His dad, Bobby Ball, drove midget cars, and “most race drivers, they don’t appreciate classical music,” Ball says. But to him, the acts of racing and experiencing music are much the same, and he still appreciates both art forms.

“In the moment, you know, music is motion. It’s that stream of notes that you hear just like listening to a babbling brook. It’s in real time. It’s in the moment,” he says. It’s like “when you’re in the middle of that turn in that sports car and anticipating. You’re looking, looking beyond where the car is now, because you’ve already anticipated that. And once again, in the moment, it’s just time, space, motion, and the beauty in moments passing.”

Jeff Ball looks back on the history of the piano.

Claire Duncombe

In 1954, Ball’s dad died from head injuries as the result of a crash. Shortly after, his mom met Roy Johnson, and the family moved to Colorado, setting the stage for their purchase of the piano in 1959.

After Ball’s family restored the piano in the early 1960s, it decorated their home in Sterling for over a decade. During those years, it functioned as a piece of furniture, because the years had taken a toll on the mechanics. However, in 1973, Ball’s mom gave the piano to her only daughter, Teresa, who took it with her to Santa Rosa, California, where she had the Proul Piano Company completely refurbish the instrument so that it could be played and heard again.

Teresa died of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1981. Ball was raising his growing family in Loveland and working at a Ford dealership at the time. A couple of years after Teresa passed away, he volunteered to drive a leased car to California and took his oldest daughter, Ulrich, along for the ride. After delivering the car, they visited with his mom, who’d moved out there, and borrowed her 1966 Mustang to drive back to Colorado – piano in tow.

The trip “darn near killed the Mustang,” Ball continues. There were steep passes when the brake pedal barely worked because the Tabor piano weighed so much, he adds.

Once it made it into the Balls’ home, the piano was part of a musical environment Ball wished to create for his five daughters. Some of them learned to read music and play on its keys, while others did their own MÁ¶tley Crüe renditions, Ulrich adds. She ended up learning to play cello, but having the piano as part of their home was a reflection of the value of music in their lives.

“That [piano] has lived even in the wake of loss,” Ball says, recalling the night his second wife died. “I called hospice, and they came over and did the certifications, and I called two guys – she wanted to be cremated – and they made house calls. It might seem macabre, but one of the guys was a very, very fine pianist, and he sat down and played for probably about three hours. It lit things up, and I viewed it as such an honor. … It was a good parting thing with music in the air.”

Jeff Ball and Rochelle Ulrich demonstrate how the cover can be closed.

Claire Duncombe

In 2014, Ball downsized, and Ulrich moved the piano to her suburban house in Commerce City. She immediately started digging into documents to better understand the Tabors’ story, because she felt it was important to know the context of the piano’s past, including its connection to the couple. Knowing their history is part of the piano’s story, and “what makes a house a home is the story behind a lot of things,” she says. “I just want to take care of [the piano] so that it can go on in the family as part of a living celebration of history, whatever it may be.”

Her sons, ages nine and ten, are currently more interested in science than music. But she never closes the piano’s lid to keep them away from the instrument.

“I like leaving it open [so] the boys have an appreciation for it, as well,” she says. “It’s something that’s accessible. They come and pound on it sometimes…make up songs, plenty of songs.”

Her sons will read under the piano, and their dog, Tabor, will often hide there to eat stolen bits of food. Friends of the family – even their nine-year-old next-door neighbor – come to play the instrument

A neighbor – one of Ulrich’s sons’ friends – enjoys coming over to play the piano.

Claire Duncombe

The piano will most likely last for many more years, says West, who has 46 years of experience working with antique pianos. If treated properly, a piano that has already withstood almost 160 years is kind of like an “Energizer bunny,” he adds.

But there are still challenges in maintaining its functionality. Because all of the keys were individually created, for example, missing or broken parts need handcrafted replacements that can’t simply be ordered from a factory. A few of the piano’s broken hammers are sitting on top of West’s workstation.

“I’m going to have to re-create them,” he says. “It’s a labor of love, in some ways.”

Even the process of tuning is labor-intensive. West says he often gets a sore back from leaning over the horizontal strings.

“I like working on [the old pianos], the stuff that’s survived,” he says. “It’s more interesting than your average instrument, because you have to use your mind and figure out what’s going on and why it’s not working right.”

The piano still demands the same kind of attention to detail that created it.

“It has that hand-loved feel to it,” Ulrich says.

Ball believes that human connection shapes the instrument’s sound, edging the notes with stories of the people in its past.

“There’s a certain spirituality about it,” he says. “It’s hard for me to explain that, but it’s something to feel. It’s kind of like gravity. You can’t put your hand on it, but you know it’s there.”